Supply chains are networks between companies and their suppliers that produce and distribute a specific product. They may include providers of raw material, firms that convert the material into products, storage facilities and distribution centers, and retailers who bring the ultimate product to consumers. The products are as varied as the marketplace: clothing, electronics, vehicles, food, medicine.

Probing the origins of commodities and products is a rich field for reporters. Investigations have revealed forced labor, environmental crimes, corruption and human rights abuses.

Yet uncovering the connections can pose significant challenges.

Many investigative tools are required to expose supply chains, to link the practices in fields, mines and factories with consumer products.

GIJN’s Supply Chain Resource Page includes research tools, reports and more. These materials supplement existing GIJN Resource Pages:

- Maritime Shipping

- Human Trafficking and Slavery (Gulf states version)

- Extractive Industries

- Corruption

For a larger perspective, read Learning Custom Languages to Track Shipments, presented at IJAsia8 by Columbia University journalism professor Giannina Segnini. She discusses the use of customs code and bills of lading, along with tracking containers and ships.

Also, watch a GIJN video with AP reporter Martha Mendoza on investigating slavery in the fishing industry.

Multi-Faceted Investigations

Reporting on supply chains is challenging for many reasons, but particularly because deception and concealment can be involved. Exposing secretive supply networks may require ingenuity and persistence. In addition, the complexity of supply chains may require cross-border collaboration among journalists in producing and consuming countries. These projects can be time-consuming and expensive.

Particularly tricky is identifying all the links in the chain. GIJN’s toolkit includes sources for information on trade documents such as Panjeva, PIERS and Enigma.

Discovering who owns small companies at the bottom of the supply chain can be difficult in light of weak disclosure laws about corporate ownership. To help track ownership, our resource list highlights Open Corporates, the Investigative Dashboard and the Business and Human Rights Resource Centre.

Reporters Expose Problems

Despite the difficulties, journalists continue to expose problems. Here are a few examples.

Repórter Brasil, working with the Bureau of Investigative New and The Guardian in 2019, traced cattle purchased by Marfrig, a Brazilian meat company that has supplied huge fast food chains, back to a farm that had grazed cows in an area of illegally felled rainforest. (See article.)

The newspaper Welt Am Sonntag in 2019 used data collated by the Bureau of Investigative News to calculate that German restaurants and retail chains used 40,000 tons of beef imported from the Brazilian giants JBS, Marfrig and Minerva.

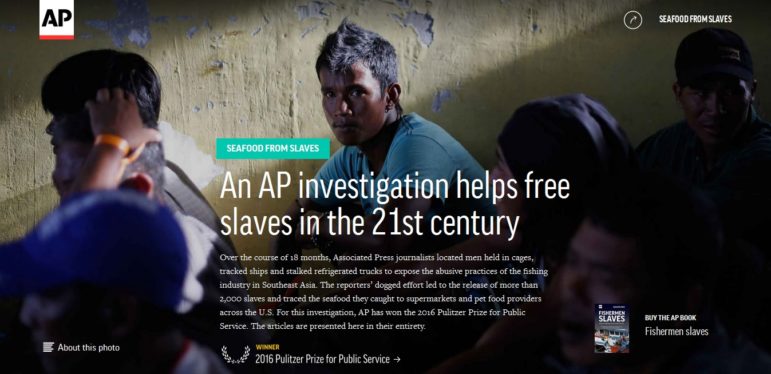

Associated Press journalists in 2016 exposed abusive practices of the fishing industry in Southeast Asia, resulting in the release of more than 2,000 slaves. They traced the seafood to supermarkets and pet food providers across the United States. For the series, AP won the 2016 Pulitzer Prize for Public Service.

AP struck again in June 2018, revealing the sale of yellowfin tuna from foreign waters, despite the US distributor’s guarantee that its products were wild. Reporters staked out America’s largest fish market, followed trucks, worked with a chef, ran DNA tests and interviewed fishermen on three continents. They traced the company’s supply chain “to migrant fishermen in foreign waters who described labor abuses, poaching and the slaughter of sharks, whales and dolphins.”

AP struck again in June 2018, revealing the sale of yellowfin tuna from foreign waters, despite the US distributor’s guarantee that its products were wild. Reporters staked out America’s largest fish market, followed trucks, worked with a chef, ran DNA tests and interviewed fishermen on three continents. They traced the company’s supply chain “to migrant fishermen in foreign waters who described labor abuses, poaching and the slaughter of sharks, whales and dolphins.”

Practices in the apparel industry have come in for a great deal of scrutiny.

The BBC in 2016 reported on Syrian refugee children making clothes in Turkish factories for Marks and Spencer and the online retailer Asos. Los Angeles Times reporters Natalie Kitroeff and Victoria Kim in 2017 wrote Behind a $13 shirt, a $6-an-hour worker, subtitled, “How Forever 21 and other retailers avoid liability for factories that underpay workers to sew their clothes.”

CBS News in March of 2018 sent correspondent Debora Patta and a crew to the Democratic Republic of Congo to report on child labor used in the mining of cobalt, a key ingredient in mobile phones and computers. “There’s such sensitivity around cobalt mining in the DRC that every few hundred feet the CBS News team was stopped, with security personnel requesting letters and documentation, even though we had official permission to be there,” CBS reported.

Using a hidden camera, CBS confirmed that cobalt purchasers in the DRC never asked whether the cobalt had been mined by children. Major companies have claimed they don’t use such cobalt.

The environmental practices of Walmart’s Chinese factories were examined in a 2013 Mother Jones article by Andy Kroll, who concluded that the company’s auditors are asleep on the job.

NGO Connections Valuable

Journalists working in this area often point to the value of alliances with non-governmental organizations, national and local, that have deep knowledge of specific sectors, such as seafood, apparel, extracted materials and electronic consumer goods. Tips about potential stories also come from local media reports, unions, community groups and law enforcement sources.

NGOs have conducted significant supply chain probes. Greenpeace’s May 2018 report, Misery at Sea, found poor labor standards, dire working conditions, and harmful fishing techniques in Taiwan’s distant-water fishing fleet. In June 2018, a global coalition of trade unions, worker rights and human rights organizations, released Gender based Violence in the H&M Garment Supply Chains.

At times, some media outlets have worked very directly with activists.

At times, some media outlets have worked very directly with activists.

In South Africa, Carte Blanche worked with arms trafficking expert Kathi Lynn Austin, who traced bullets and ammunition recovered from rhino-poaching crime scenes back to their manufacturers in the Czech Republic. Produced by Sasha Schwendenwein, the four-part series on South Africa’s longest running investigative journalism program involved reporting in Mozambique, Portugal, South Africa and the United States staking out and interviewing many business owners; digging into public records and using hidden cameras.

Leveraging Corporate Behavior

The power of supply chain research derives largely from the pressure that can be exerted at the highest levels of ownership and responsibility.

There has been a steady increase in the numbers of international norms and laws to regulate corporate behavior. A variety of systems rating corporations have been created, some by governments, others by NGOs, such as Know the Chain, Turning Point and Corporate Human Rights Benchmark.

The increased pressure on corporations to find and solve potential problems in their supply chains has spawned an industry of consultants who help corporations conduct “due diligence” on their operations. One such firm, RepRisk, boasts: “Using a proprietary IT tool, RepRisk screens over 80,000 media and stakeholder sources every day. For the earliest identification of risks, this screening is executed in 15 languages.”

But don’t expect much transparency from this quarter. Consultants’ reports to corporations about potential problems and corporate records on their supply chains are rarely available to the press. Some journalists have found sources at firms specializing in socially responsible investments.

Greater disclosure by companies has resulted from some laws, such as the 2010 California Transparency in Supply Chains Act and the 2015 Modern Slavery Bill in the United Kingdom.

Eventually, more public transparency may reach store shelves.

Technology creates the opportunity in some parts of the world for shoppers to scan food labels with their phones and see where products were made, by whom and under what conditions. But implementation of such transparency is far from being widespread today.

Media Impact a Factor

Media coverage can have a significant impact.

A 2017 study in Strategic Management Journal concluded that “negative media articles regarding environmental, social, and governance (ESG) issues increase a firm’s credit risk.”

And sometimes workers’ lives are saved. AP reporter Martha Mendoza and colleagues conducted an 18-month investigation that led to freedom for 2,000 men forced to work on Indonesian fishing boats.

Because of the persistent nature of human rights violations, follow-up is necessary, said Nichole Pope, an independent journalist and a researcher/writer for NGOs. “Sometimes, this element is missing,” she said, explaining that when “violations are exposed in a big brand’s supplier factories — child labor for instance — the brand’s instinct is usually to cut and run. They make big announcements, say they didn’t know and will immediately stop working with said supplier, and hope the scandal dies down.”

But the story doesn’t end there. When a factory loses a big contract from a major brand, this may mean hundreds of workers lose their jobs and ultimately won’t help the victims. Journalists who uncover the violations should also ensure that the brands do something to remedy the situation and actually help the workers whose rights were violated. The pressure of big brands on prices and delivery dates, especially in garments, are often a big part of the problem in the first place.

Finally, reporting in this area is potentially dangerous. Journalists doing field work in remote places like Indonesia (for palm oil manufacturing) have faced threats and physical harm. Reporter Gaspar Matalaev remains imprisoned in Turkmenistan after investigating forced labor in the cotton sector and is suffering from ill health, according to the International Labor Rights Forum and The Independent.

This guide was put together by Toby McIntosh, director of GIJN’s Resource Center. He was with Bloomberg BNA in Washington for 39 years. He is the former editor of FreedomInfo.org (2010-2017), where he wrote about FOI policies worldwide, and serves on the steering committee of FOIANet, an international network of FOI advocates.

This guide was put together by Toby McIntosh, director of GIJN’s Resource Center. He was with Bloomberg BNA in Washington for 39 years. He is the former editor of FreedomInfo.org (2010-2017), where he wrote about FOI policies worldwide, and serves on the steering committee of FOIANet, an international network of FOI advocates.