Better to focus on the demonstrated negative impact of trafficking on plant and animal populations.

“Given the ambiguities inherent in defining IWT,” a 2019 review by academics at Oxford University concluded, “measuring it is challenging (if not impossible) to do with accuracy, and there are no available methods that can produce a global estimate of the species and quantities involved.” Another critical review was done in 2020 by journalist John Cusak for Financial Crime News.

The recurrent figure used by the media and NGOs states that IWT ranges from $5-$23 billion per year. The high number is actually a 2007 estimate of legal wildlife trade made in a 2007 TRAFFIC report.

What does this mean for journalists writing a “global” story about IWT, who are understandably desirous of setting the scene with data?

It is safe to say that IWT is a multi-billion dollar market. But the magnitude is hard to precisely fix. So be general, for example:

“Billions of dollars are spent on buying illegal plants and animals, but the exact magnitude is unknowable by the very nature of this secretive business.”

Note: there’s much more illegal fishing and timbering and while the estimates for those are also very general, they are considered more credible than those for IWT.

Also suspect are the assumptions used for converting the weight of seizures into numbers of animals killed. The weights of pangolins, in particular, vary. (See footnote 43 of the C4ADS report Tipping the Scales.)

Impact Beyond Money

Using a monetary gauge deflects attention from the arguably more important fact that significant damage is being done to plant and animal populations. Several major studies document drastic declines in biodiversity, and new ones appear frequently.

The most inclusive is from the United Nations, the IPBES Global Assessment Report on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services. The 2019 report estimates that “one million animal and plant species are now threatened with extinction, many within decades, more than ever before in human history.”

Similarly, an analysis published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences in 2020, shows that more than 500 species of vertebrates are now on the brink of extinction within the next two decades.

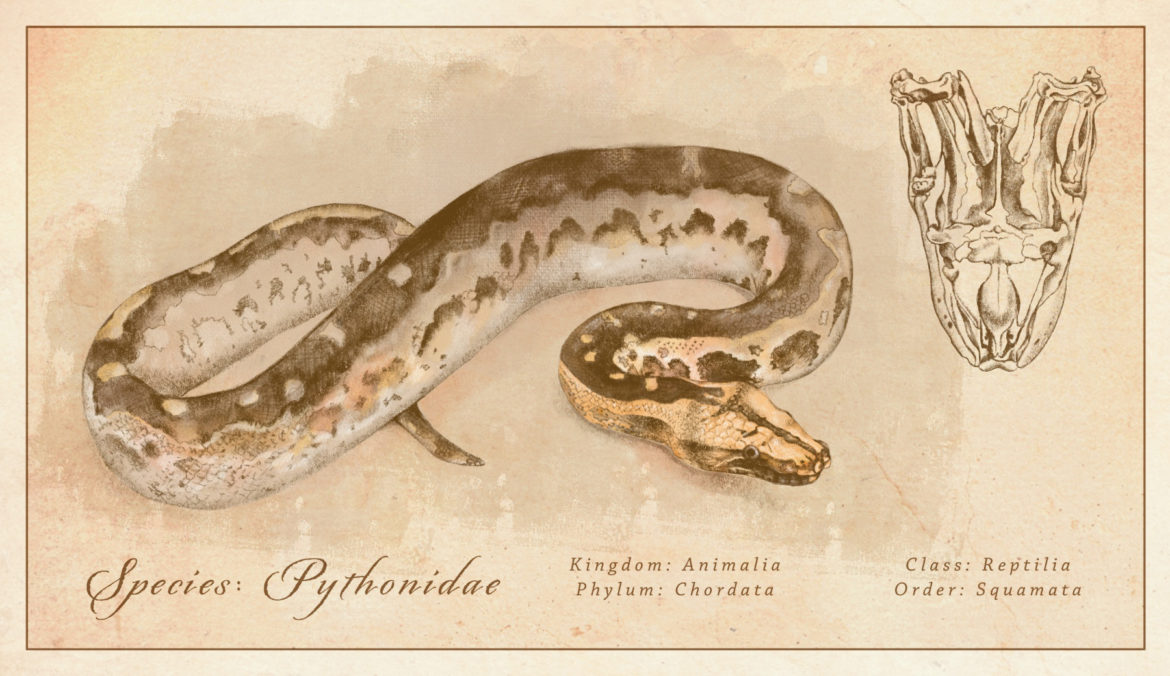

Illustration: Marcelle Louw for GIJN

The World Wildlife Fund (WWF) Living Planet Index reveals an average decline of 68% in vertebrate species numbers between 1970 and 2016, a decline the authors describe as “catastrophic.”

Assessing the impact of IWT as a factor in global declines is complicated. Other factors, such as climate change and deforestation contribute significantly.

A study published in Nature (partially behind a paywall) in 2021 attributed 62% of the decline in species to trade, legal and illegal. “The analysis also highlights a gaping hole in wildlife research,” according to an article about the study in Science.

The best documentation is available on trade involving the more iconic animals: elephants, rhinos, big cats, and pangolin.

In addition, fairly reliable numbers may be available for some other specific plants and animals and for defined geographic areas. For these, look to local and species-specific experts and search in the scientific literature.

Species Databases

Many resources exist from which to gather information on threatened species. They include:

Checklist of CITES Species allows the exploration of more than 36,000 species of animals and plants and their degree of protection.

The Red List of Threatened Species, by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), is a comprehensive and authoritative inventory for the global conservation status of animal, plant, and fungus species.

Species+ includes information on taxonomy, legislation, distribution, and trade in species listed in multilateral environmental agreements. Managed by the UNEP-WCMC and the CITES Secretariat.

A list of databases is included in GIJN’s spreadsheet on IWT.

Legal Trade Hard to Value

Valuation provided in the legal trade reports by the authorities is often missing or understated, so the reported illegal trade value is also inaccurate.

“Shortcomings in CITES data,” according to a 2021 paper by researchers at the University of Hong Kong, “include inconsistent reporting practices across parties, the use of multiple un-standardized measurement units, no value declarations, and reporting to different taxonomic levels.”

This same study used the UN International Trade Statistics Database (UN Comtrade) to estimate legal trade for the period 1997 and 2016. The annual average wildlife trade was $220 billion, with about 80% of that in seafood.

The lesson for journalists? Downplay monetization.

Understanding the Legal Basics: International and National

International trade in wildlife is covered by a major international treaty and by national laws. The sufficiency and efficacy of these protections remain much debated. Journalists who report on IWT strongly recommend learning about both the international regime and national laws.

The key international treaty is the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES), to which 183 nations are now parties. CITES requires participating countries to penalize trade that violates its provisions but does not dictate national laws. (See CITES website.)

CITES currently categorizes more than 38,700 species (more than 32,800 plants and around 5,950 animals) into three “appendices,” depending on the degree of protection needed.

International trade is prohibited for some 1,000 species, threatened with extinction (CITES Appendix I), with very limited exceptions. Fewer controls are placed on trade in species that are not necessarily threatened with extinction but whose survival could be threatened by international commercial trade (Appendix II).

Legal trade “should normally be accompanied by a CITES permit or certificate,” according to a CITES website description.

Fraudulent licensing is a major issue (and potential story). Many exporting countries lack electronic systems, making traceability of shipments difficult. See the overview on this topic from TRAFFIC director of policy, Sabri Zain.

For more see the CITES website and Species+, a database that contains information on all species listed in the appendices of CITES and by the Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals.

International Negotiations

The parties to CITES meet every two to three years at the Conference of the Parties (CoPs) to review the implementation of the Convention. The next one, CoP19, will be held in 2022 in Costa Rica. These large meetings last for about two weeks.

Among the usual hot topics is how to categorize species. While debate about whether a particular animal is in danger of extinction may seem to be a scientific question, it can become very political, with countries trading votes.

In the shadow of COVID-19, one proposal is to amend CITES to include public health and animal health criteria in its decision-making processes. (See a description of the proposal by the alliance End Wildlife Crime, which posts resources on this and other reform proposals.)

Also being advocated is the addition of a protocol on IWT to the UN Convention on Transnational Organized Crime. (See this description of the initiative by End Wildlife Crime.)

Press coverage of the meetings themselves is often limited, and very little is written in between the conferences.

One exception, investigating the influences on decision makers, was done by BuzzFeed contributor Roberto Jurkschat. He reported that trophy hunters and luxury fashion brands exert influence on the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), one of the world’s largest and most prestigious conservation organizations, to expand the billion-dollar trade in endangered animal species. See: Inside the Global Conservation Organization Infiltrated by Trophy Hunters.

Connecting with major NGOs may be the best way to find possible stories. See this overview by the World Wildlife Fund, Corrupting Trade: An Overview of Corruption Issues in Illicit Wildlife Trade.

For example, a major complaint in 2021 alleged that the Asian elephant trade between Laos and China has been potentially breaching CITES rules for years. The allegations cast further doubt on whether CITES is fit for purpose.

Decisions made at the meeting may provide reporting hooks, such as about how new regulations affect the operations of zoos and exporters.

The World Health Organization also has a role because of the connection with animals and disease, and even remedies. Some campaigners are petitioning WHO for a global ban on commercial wildlife markets.

National Laws and Enforcement

Understanding national laws is essential grounding for journalists exploring IWT. Nations adhering to CITES can adopt their own standards for trade within their borders, and national laws vary widely. There are different laws on poaching, different burdens of proof, and different penalties.

One good source for the national laws in 71 countries is Legal Atlas (registration required). Legal Atlas covers many categories of laws related to IWT, such as those concerning money laundering, corruption, and firearms.

“If there is crime at the destination, there is likely a crime at the source,” James Wingard, Legal Atlas’s co-founder said.

Legal Atlas also publishes periodic reports such as a 2021 report Fighting This Year’s Virus With Last Year’s Law, and the 2019 reports, Legal Protection of Great Apes and Gibbons and Following the Money, which found that anti-money laundering laws in 45 of 110 countries were inadequate for fighting IWT.

Other interesting reporting might delve into whether the laws need to change and where resistance to reform comes from.

- For example, The Legal Proposals Shaping the Future of Wildlife in China, a China Dialogue article by Wang Chen and Jiang Yifan.

- Game Over for China’s Wildlife Food Trade, But Does Ban go Far Enough? asked Jane Cai and Guo Rui in the South China Morning Post.

The quality of the laws is only part of the picture. Their enforcement is also crucial. Interrogating the administration of the laws involves looking at the relevant budgets, the people resources deployed, and the results, among other things.

Abby Guen, for the Washington, DC-based NGO Global Financial Integrity, looked at these questions in Out of Sight: Wildlife Trafficking Responses in Colombia.

“Countries come up with new policies all the time and it is in your best interest as a journalist to get acquainted with updated policies,” advised Esther Nakazzi, a freelance science journalist and Internews trainer for South Sudan.

An unusual national story? Ask about what is being done to study wildlife pathogens.

Even technical issues may be worth exploring. Many national customs and CITES Management Authorities in exporting countries do not have automated processes, limiting traceability.

The International Consortium on Combating Wildlife Crime (ICCWC) is a collaborative effort of five inter-governmental organizations working to bring coordinated support to the national wildlife law enforcement agencies and to the sub-regional and regional networks. The ICCWC Indicator Framework for Combating Wildlife and Forest Crime is a 50-point tool to assess enforcement and criminal justice responses.