However, there is too much focus on poaching and not enough on trafficking, according to Andrea Crosta, executive director of Earth League International, an NGO that investigates wildlife crime and runs WildLeaks. “We know what happens at poaching level and at the end of the supply change,” Crosta said, but “little” about “the middle.”

It’s a big challenge. A range of investigative skills are necessary.

To delve into trafficking routes, consider cultivating sources in the transportation world, such as customs agents, freight handlers, and truckers.

Documents become more important as goods get moved, often with falsified papers.

In this section we’ll address:

- Learning about routes.

- Trade documents.

- What seizure records say.

- Following financial flows.

- And the interplay between the legal and illegal trade.

Corruption: An Overriding Consideration

“Corruption is the major enabler of wildlife crime,” said Stephen Carmody, chief of investigations for the NGO Wildlife Justice Commission, during an October 2020 webinar.

This observation isn’t controversial. But recognizing the major role corruption plays is critical to reporting on IWT. For a good overview of the many faces of corruption see this report by Sabri Zain, the director of policy at TRAFFIC.

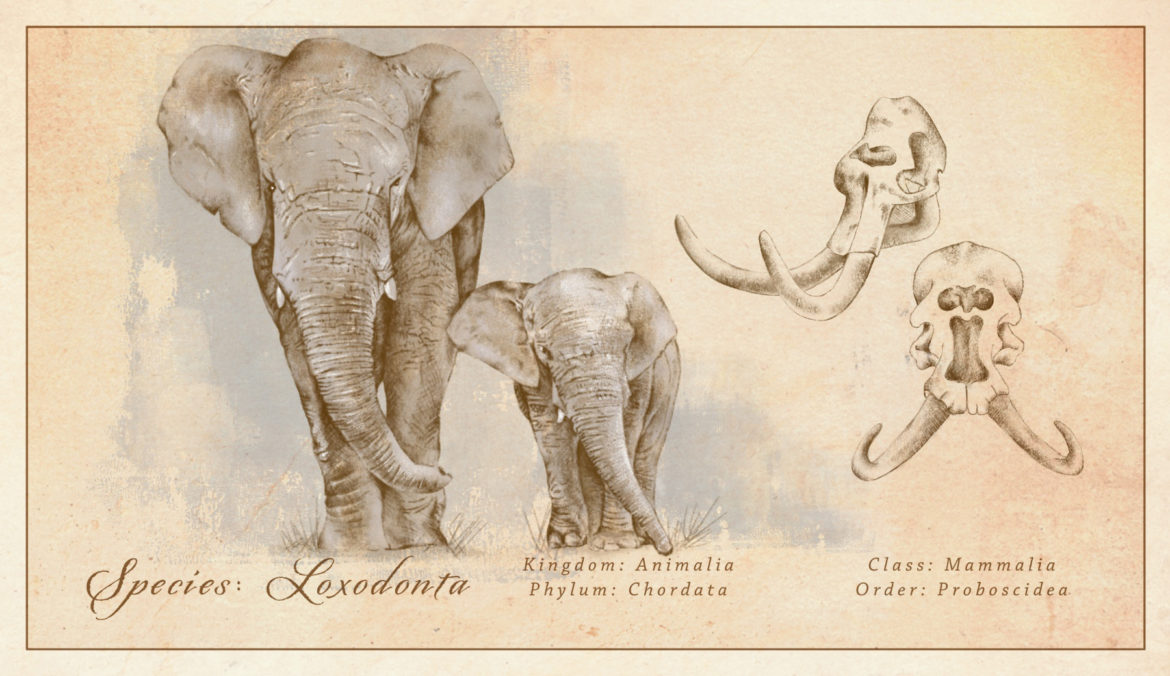

Illustration: Marcelle Louw for GIJN

“If we follow the scoop and scandal, if we follow the ivory alone, but not the system in which the ivory is being traded, it’s here today and gone tomorrow and we are yacking and chasing behind them,” said Khadija Sharife, senior editor for Africa at the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP) during a March 2021 webinar.

Although IWT is often described as the work of organized crime, “disorganized crime” is the term preferred by Carmody. Elaborating on his point, a study by Northumbria University researcher Tanya Wyatt and others notes: “The criminal networks engaging in wildlife trafficking are diverse.”

A comprehensive description of how IWT works and is financed can be found in Money Laundering and the Illegal Wildlife Trade by the Financial Action Task Force, an inter-governmental body.

Another good look at corruption is this Traffic report, which examines individual cases and identifies specific red flag indicators, criminal network diagrams, lists of associated high-risk entities, and data on the convergence between wildlife and other crimes.

Going Undercover

Undercover work to expose IWT is standard operating procedure for law enforcement officials, NGO researchers, and sometimes journalists.

To visit a bizarre casino in Laos, “a playground of illicit delights ranging from drugs and prostitution to illegal ivory and rhino horn,” American reporter Rachel Love Nuwer went with a friend and her husband. She dressed as an Eastern European prostitute with a hidden camera disguised in a garish pink watch, as described in her 2018 book, “Poached.”

Reporters have used disguises and false stories to:

- Make purchases of illegal products.

- Expose officials willing to take bribes.

- Visit restaurants that serve illegal meats.

But be cautious: Undercover work can be very risky and safety precautions are critical.

Julian Rademeyer, who wrote the book “Killing for Profit: Exposing the Illegal Rhino Horn Trade,” said: “Undercover investigations do have a role to play but, in my view, should be a last resort.”

Elaborating on his reasoning, Rademer said:

“Too often undercover investigations are done simply for the sake of doing them to add drama and suspense to a story and recklessly show off spy cameras and gadgetry.

“They need to have a very specific purpose that cannot be achieved in any other way and that will significantly enhance the story you are trying to tell. You first need to weigh up whether you can get the information you need by any other means, you need to consider the very real risks of being caught out, you need to have support and a backup plan in place.

“I would caution against ever buying wildlife products or creating the impression that you want to buy a specific product. It is an ethical minefield and the unforeseen consequences can be great. For example, a seller may not have the animal or wildlife product you are looking for in stock but your interest in purchasing it will lead them to find it for you. Wildlife will die. Secondly, as a journalist, you should not in any way support the illicit markets you are investigating. Leave buy-busts to cops and investigators.”

Esther Nakazzi, a freelance science journalist and Internews trainer for South Sudan, says: “The people you are dealing with in environmental crime are already criminals, they can be violent.” If you go to a rendezvous, share your location with someone, she recommends.

To be successful as a pretend buyer, she says you will need to be convincing, so “believe in your cover,” “keep it businesslike,” and “talk like you have the cash.”

Undercover work to probe international networks is particularly difficult and time-consuming. One of the NGOs doing undercover work is Earth League International (ELI), which has several long-term operations. With Operation Fake Gold, ELI has been working for over three years to infiltrate trafficking network operations for the “Totoaba cartels” operating in Mexico and China.

Also see the related section on undercover research via social media.

Story Examples

Less risky reporting can result in impressive stories, relying on interviews with experts and data. Here are some examples:

Traffickers v. COVID-19 by Trang Bui and Lam Quan with the Environmental Reporting Collective and the Vietnam-based Centre for Media and Development Initiatives, used undercover interviews and databases to learn that traders “seemed unperturbed” by the pandemic and “are simply waiting for travel restrictions to lift so they can resume business – and perhaps even up the ante.”

Tipping the Scales: Exposing the Growing Trade of African Pangolins into China’s Traditional Medicine Industry is a report by the NGO C4ADS using its own data (available to reporters, see below).

The Elephant Pricing Scam, by Karl Ammann, uses a variety of documents to examine irregularities in the sale of elephants from Zimbabwe to China.

Many types of data were used for this article, Pangolins in Cameroon Are On the Verge of Extinction, by Abhijit Mohanty, a freelance journalist based in New Delhi, in Down to Earth.

The section on Indonesia in The Pangolin Reports describes retracing some recent seizures and finding indications of an extensive trade network.

For more examples, see the GIJN spreadsheet.

Of interest, but out of the range of most journalists, are special, ingenious tools used to catch poachers and traffickers, such as fake turtle eggs with transmitters, or sniffer dogs for cargo containers. Also, the WildScan smartphone app enables the identification of commonly trafficked wildlife and wildlife parts.

Many Tricks, Many Routes

Jet passengers tape animals to their bodies. Illegal cargoes are hidden in shipping containers with legal cargo. Finches are found in hair rollers. Snakes are stuffed into bottles. A suitcase stuffed with 185 baby giant tortoises wrapped in plastic. Using inventive and often cruel techniques such as these, traffickers undertake all manner of transportation modes: usually ground transport for the initial and final stages, but air or sea for international trade.

Plenty is known about the usual routes.

Among the places to find more information about these IWT supply streams is the USAID Reducing Opportunities for Unlawful Transport of Endangered Species (ROUTES) Partnership. Keep up on periodic country-specific ROUTES assessments here. TradeMapper is a visualization of trade routes using CITES trade data or other data sources.

A 2021 ROUTES report, Shared Skies, is about the convergence of IWT with other crimes. Also see a ROUTES report, Flying Under the Radar. More on the USAID/C4ADS Air Seizure Database in a minute.

A 2020 report by the Wildlife Justice Commission looks at changing patterns and the increased convergence in the shipping of pangolin scales and ivory.

Falsified Documentation

Smuggling often involves misrepresenting the true contents of a shipment. Wildlife contraband may be disguised among legitimate goods. Bribes often smooth the way through customs checkpoints, border crossings, airports, or seaports.

Proper documentation is required for the legal sale of wildlife and wildlife products. Here is a good explanation of the types of documents required, for exports and imports and more.

This brief by TRAFFIC also discusses common corruption techniques, such as the intentional declaration of false information on documents, documents modified after issuance, unofficial payment for documents, and counterfeit documents.

The UN Comtrade Database is a repository of official international trade statistics. Though its focus is on legal animal trade, comparing import and export information has revealed interesting disparities and other leads.

“When there are major discrepancies, such as the importing country reports twice as many imports as the exporter claims to have exported, you have a discrepancy to analyze,” said Giannina Segnini, director of the Data Journalism Program at Columbia University. “Then you start gathering more granular information, such as bills of lading that show the specific vessel, port, date, etc. from commercial databases and other sources, and you start looking for patterns and clues.” (See her slides on this topic here.)

The Comtrade database often lumps various animal/wildlife products together so you need to make sure that you understand the codes.

Documents about shipments, known as “bills of lading,” can be gold mines — containing the name of the party doing the shipping, where it is going and to whom, and signatures. Unfortunately, they are not public records in many countries. But they are available in the US, India, and a number of Latin American countries, including Panama and Peru.

Bills of lading, obscurely sourced, were key to this story by the group Animal Wellness Action about the trafficking of fighting birds to the US.

Using trade records of various kinds may lead to the names of the importers or exporters, often front companies, and people involved. Some journalists find value in commercial service databases about trade, such as Panjiva and Import Genius. See also GIJN’s resources such as Tracking Ships at Sea and Investigating the Supply Chain for more. A related presentation by Segnini addresses topics such as researching shipping containers and bills of lading. Also helpful is her primer on Learning Custom Languages to Track Shipments.

Many open source investigative skills are needed to dig further into corporate ownership. For that, see the GIJN resource on Researching Companies.

Using Seizure Records

Seizure records are kept at the national and international levels and assembled by several NGOs.

These records may provide journalists with useful leads on trafficking. They also are helpful for analyzing national law enforcement efforts, showing trends, mapping trafficking routes, and providing context.

Nearly 6,000 species were seized between 1999-2018, according to UNODC’s 2020 World Wildlife Crime Report. No single species is responsible for more than 5% of the seizure incidents and virtually every country in the world plays a role. The UNODC’s World Wildlife Seizure database (World Wise), described here, is not public.

Several nongovernmental organizations have stepped in to fill the data gap, however.

Illustration: Marcelle Louw for GIJN

One such source is the Wildlife Seizure Database, maintained by the Washington, D.C-based NGO C4ADS. Note: Access is by request only. It contains over 5,000 records of ivory, rhino horn, and pangolin seizures tracing back to 2009 as well as tiger and leopard seizures since 2014. The C4ADS database is maintained using publicly available information including media reports on seizures in over 15 languages and monitoring of customs’ reports. See a 2020 report on the African pangolin trade to understand the many uses of the database. Between 2015 and 2019, 55 known shipments of pangolins or pangolin products transited Nigeria and only 11 of them (20%) were intercepted within Nigeria, C4ADS found.

The Wildlife Trade Portal is an interactive tool that displays TRAFFIC’s open source wildlife seizure and incident data (but you must request access). The portal is searchable, with results displayed not only as a list but also in a dashboard format. Individual entries offer more in-depth information about a specific incident, such as the exact species, commodities, and locations involved. The results can be exported to CSV format for further analysis. For more information about how to use the portal, please refer to the user guide.

The Environmental Investigation Agency (EIA) in the UK has posted data from publicly available information on seizures and prosecutions. EIA’s search effort focuses on elephants, rhinos, pangolins, tigers, leopards, snow leopards, clouded leopards, totoaba fish, and various species of timber.

The USAID Reducing Opportunities for Unlawful Transport of Endangered Species (ROUTES) Partnership is a coalition of partners brought together by the US Agency for International Development. The ROUTES Dashboard is an interactive website providing graphics on wildlife trafficking through airports between 2009 and 2020. The graphics are derived from data collected by C4ADS. See past ROUTES reports, Runway to Extinction (2020), In Plane Sight (2018), and Flying Under the Radar (2017)

Perhaps amusing to journalists, but actually instructive, is guidance created by ROUTES for government customs officers on the kind of information that should be included in press releases about IWT seizures. It points out excellent questions to ask.

For a detailed discussion on valuing seizures see the Methodological Annex to the 2nd edition of the World Wildlife Crime Report.

The World Customs Organization (WCO) sets standards for national reporting on seizures and collects national data. However, the resulting Customs Enforcement Network (CEN) repository is not made public.

In addition to the national information available from the databases cited above, most individual national governments keep seizure records digitally or on paper. See if a centralized database exists. Ask for the raw data to conduct your own analysis.

Impunity and Incompetence Fuel Illegal Mexico-China Seahorse Trade, an article by Joanne Lee for Diálogo Chino, states:

“Between 2001 and 2019, traffickers attempted to smuggle 95,589 seahorses out of Mexico, according to the Federal Environmental Protection Agency (Profepa). However, it is likely that the real figure is much higher given that there is considerable under-reporting from Mexican authorities.

“Of this total, 64% were destined for Hong Kong, Beijing, and Shanghai. The rest went to the local Mexican market, records of Profepa seizures obtained by Diálogo Chino under Mexico’s Transparency Law show.”

The Oxpeckers Centre for Investigative Environmental Journalism, a South Africa-based investigative journalism nonprofit, sponsors WildEye, a tool designed by journalists for journalists to track seizures, arrests, court cases, and convictions relating to wildlife crime across Europe. WildEye Asia does the same for Asia.

This AllAfrica news article covers the release of Namibia’s 2020 IWT statistics and compares it to previous years.

However, access to national data may be difficult. Getting such information from the US Fish and Wildlife Service requires filing a freedom of information request.

This report by the EIA documents gaps in data and lack of government transparency about wildlife trafficking.

Mining the CITES Trade Database

As mentioned earlier, the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora — or CITES — is an international agreement between governments. The CITES Trade Database is the largest dataset on legal international trade in extinct and near-extinct species. It has historical data back through 1975 on species listed in the CITES Appendices. For trends see the CITES Trade Database.

A 2021 academic study by Jia Huan Liew and colleagues, published in Science magazine, deeply analyzed the CITES data. Among other things, it concluded that the largest exporters of wild animals in the trade between 1998 and 2018 were Indonesia, Jamaica, and Honduras. The US was the biggest importer, with France and Italy second and third, respectively.

Anuja Venkatachalam, a data analyst with Health Analytics Asia, provided GIJN with some suggestions based on her experience with a major project that found that China’s attempts to curb wildlife trade in the aftermath of SARS in 2003 were short-lived.

The CITES database includes the following variables:

- Year (from 1975 to 2020).

- Export and import country.

- Source (where the plant/animal is sourced from — whether it is a wild species, or captive-bred, for example).

- Purpose (why it is being traded, as disclosed by the exporter/importer).

- Trade terms (the name of the specific body part of the species and the form of the final product — whether live/skin/bone, etc.).

- Taxonomy (the biological term for the species).

The official guide provides full definitions.

“Because this is a large dataset, it is recommended that you break it down into years/export-import country/purpose/source/taxonomy,” said Venkatachalam, who elaborated on the following challenges in processing the dataset:

- “This is a large-scale dataset. So, you will most likely need to process it using programming languages such as python or R. You might still run into memory issues with these languages, so you can either use a server linked to colab or run files one by one, screening only those data you require for your analysis.

- The quantities mentioned in the dataset can be challenging to report on. For example, live animals are reported in numbers whereas finished products are reported in kilograms or grams. There is no data on value, so it’s hard to make comparisons. Moreover, some commodities are missing quantity data, so you will mostly end up counting in terms of transactions.

- There have been changes in reporting regulations. So, you are more likely to find data for later years. This does not always mean that more trade transactions were made. It might be the case that they are getting reported because of changes in regulations. The same official guide linked above includes the full list of changes.”

Deficiencies of the CITES database are well-documented: a lack of standardization and absent data being primary concerns. The country reports are considered particularly suspect. See one such commentary here.

However, Ceres Kam, a wildlife campaigner for EIA, said: “Sometimes one can find documents on the CITES website that reveal data for certain years and certain species, such as progress reports by countries on their National Ivory Action Plans (NIAPs).” For example, for Nigeria. Figures also may appear in biennial and implementation reports such as this one on China.

The Ties Linking Legal and Illegal Markets

Experts report that legal trade is often used as a front for illegally obtained products.

The intermingling involves trade in seafood, pets, zoos, breeding, food, medicine, jewelry, cosmetics and perfume, fashion, and furniture. Legal industries can be contaminated by the introduction of illegal supplies.

Illustration: Marcelle Louw for GIJN

Because there are records about legal trade, the complex relationship with the darker underbelly of this market may be explored.

For example, Oxpeckers’ Calistus Bosaletswe used CITES data to show that over a 10-year period South Africa received most of the live lions and their byproducts exported from Botswana. The figures raise policy questions, such as whether the exports undercut the moratorium on the hunting of lions in neighboring Botswana.

Legitimate breeders, pet stores, and private zoos also may be fronts for illicit trade.

The use of products derived from wildlife is legal in many countries, sometimes with official oversight. Decisions on what products to allow can be controversial.

Regulation may provide openings for reporting. For example, in China, hospitals are authorized to use certain products for medicinal purposes. China in 2015 disclosed a list (in Chinese) of 711 hospitals authorized to buy and use unprocessed pangolin scales. This is potentially useful information because of the cross-over between the legal and illegal markets.

The C4ADS Tipping the Scales project identified more than 1,000 companies, hospitals, and other entities participating in China’s legal market for medicinal pangolin products. “In this market, which allows companies to privately stockpile pangolin scales, traffickers exploit lax regulations to sell scales from Africa and Asia,” C4ADS said. The report has a section on the legal Chinese pangolin scale system and how it works.

Other things to study: companies that legally produce wildlife-derived products, and the records of related patent applications. Also bear in mind that animal breeders sometimes cross the line into illegal activity.

Following Financial Flows

The traditional exhortation to “follow the money” remains applicable, although reporters typically don’t get help from financial institutions the way official investigators can.

“The financial flow is the breadcrumb trail,” said Robert Campbell of the United for Wildlife Transportation Taskforce. There’s a parallel United for Wildlife Financial Task Force. Both aim to encourage businesses to address IWT by developing due diligence procedures and prioritizing financial analysis associated with wildlife crime.

At the lowest levels of the supply chain, cash is most commonly used. Encouragingly, Carmody observed that wildlife traffickers use “poor tradecraft” compared with drug traffickers.

Money Laundering and the Illegal Wildlife Trade by the Financial Action Task Force says “criminals are frequently misusing the legitimate wildlife trade, as well as other import-export type businesses, as a front to move and hide illegal proceeds from wildlife crimes.”

Secret Stockpiles

In some countries, valuable stockpiles exist of seized goods, such as pangolin scales and rhino horns. This might not seem to be a good place to look for stories, but it can be.

Mismanagement has been discovered and stockpiles have at times mysteriously shrunk. Ask about the stockpile levels and how they are being handled.

The use of these caches, such as whether to sell them or destroy them, has become controversial in some places. For more on the policy issues involved, see a CITES background paper on stockpile management. Ask for reports on the levels of the stockpile and on transactions.