Caution is advised. Poachers and traffickers may be armed and dangerous. Law enforcement officials, with better tools and training, run into trouble all too frequently. Two Spanish journalists filming a documentary on poaching in Burkina Faso were murdered in an ambush in early 2021. Reporting on official complacency and corruption also may pose security risks.

Nevertheless, ground-level investigations may provide insight into who is doing the poaching and why. Reporters often tag along with wildlife protectors and law officers to get first-hand insight and gain ideas for further investigation. Clues may emerge on who is involved at the next rung up — intermediary buyers, transporters, and dealers. This level also may be the first place to see indications of corruption.

There are other potential advantages to first-hand reporting. For one thing, revealing the gruesome details of poaching has impact. Words and pictures can graphically illustrate the destruction.

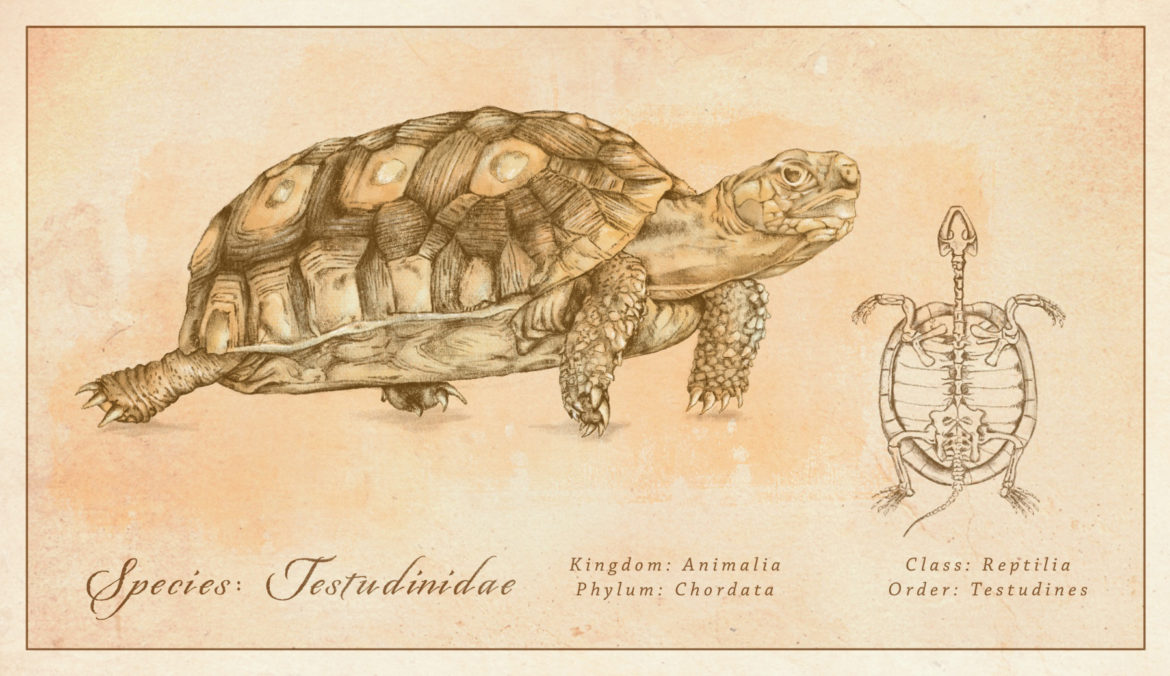

Illustration: Marcelle Louw for GIJN

Working closely with wildlife defenders, broadly defined, may well result in acquiring leads to other good stories. And not necessarily just about criminal perpetrators. Stereotypes might be challenged. The standard image of a hunter carrying a big game rifle misrepresents the many types of poaching. Why poaching occurs may be better illuminated, as a result.

“An important part of combating wildlife crime is recognizing that poverty is a driver of it,” said Ian Redmond, a tropical field biologist and conservationist. “It’s no excuse, but it helps you to understand if some of the crime is actually poor people following their traditional way of life.”

Talking to the communities around protected areas and interviewing families of poachers who had been killed may provide valuable information and lead to introductions to poachers.

Here are a few examples:

The Hard-Knock Life of a Indonesian Bird Catcher, by Mustafa Silalahi for Tempo Magazine, reveals the details and motivations of a bird catcher. It’s a companion piece to an article by Silalahi on songbird trafficking.

Dina Fine Maron’s Inside Florida’s Alleged Flying Squirrel Smuggling Operation for National Geographic.

Donkey Rustlers Profit Off Wildlife Trafficking Routes, an Oxpeckers story by Oscar Nkala.

A study by the Basel Institute on Governance (an NGO), Wildlife Trafficking in Uganda: Poverty, Governance, and Perceptions, delved into public perceptions of IWT, with conclusions such as: “Utilitarian perspectives of wildlife, alongside characterisations of wildlife trafficking as a benign, legitimate form of informal trade that brings wealth and status, fuels the social acceptability of wildlife trafficking.”

Probe Enforcement Systems

Being at the source also may reveal whether efforts to prevent poaching are successful or hampered, and why. Stories might include:

- Whether resource deficits affect enforcement work.

- If enforcement strategies are effective.

- If there are conflicts with local communities.

- Whether conservation strategies are working.

Follow the Guns

One unusual investigative technique to uncover poaching is to follow the guns.

Kathi Lynn Austin of the Conflict Awareness Project (CAP) tracked poachers’ rifles by using their serial numbers. For more, see Follow The Guns: An Overlooked Key to Combat Rhino Poaching and Wildlife Crime and the CAP website.

“Much attention has been directed at the financial, transport, and online web sectors, but we also believe that efforts to address the proliferation, trafficking, and diversion of guns to criminal organizations should be prioritized both on the national and international levels,” according to Austin.

Talk to Convicted Poachers and Traffickers

Some researchers have found that interviewing incarcerated poachers and traffickers can be a gold mine of information.

A TRAFFIC study in 2020, Insights from the Incarcerated: An Assessment of the Illicit Supply Chain in Wildlife in South Africa, was based on interviews with offenders to understand their motivations in engaging in wildlife crime.

In Nepal, academic researchers in 2019 reported complex motivations and stories from those incarcerated for IWT. They were poor, but trafficking wasn’t their primary work. Many were affected by peer pressure. Most were not explicitly linked to organized crime.

Another insiders’ account can be found in The Pangolin Reports: “At the Lo Wu Correctional Institution, a prison, we found two small-time traffickers who were willing to discuss their actions,” the authors wrote.

The New York Times story by Denise Hruby — He Once Trafficked in Rare Birds. Now, He Tells How It’s Done — is also of note.