There are few independent, locally-registered media outlets in the GCC, and much of the reporting on the region is carried out by either those who are based in the region reporting to media outside it or those who visit the countries often to report on it. Both these groups face constraints in access to information and security. These five testimonials from reporters with experience working in the GCC help to offer a sense of what it means to write about forced labor from within and remotely.

Working Around Political Constraints

Sebastian Castelier is a freelance journalist who reports on GCC economies for several Middle Eastern and international publications; his work has been published in multiple languages.

“Reporting about the devastating impact the COVID-19-induced crisis is having on migrant worker communities is proving to be challenging. Most countries in the Arab Gulf region have closed their borders for months and/or restricted movements. Such a situation has had a profound impact on the ability to produce field reporting, forcing most journalists to rely on phone and video interviews to highlight the unprecedented struggle faced by migrant workers.

“Parallel to constraints accessing the region, the intensity of the crisis led many migrant workers to reach out to journalists, most often via social networks, to share their personal stories or request help. But given the current political context and the information war raging between the UAE/Saudi axis and the emirate of Qatar since 2017, the veracity of testimony received needs careful verification. Not to mention that the vast majority of private companies deny any wrongdoing and question the accuracy of any worker testimony we collect. The suffering of migrant workers in the Gulf has been politicized.”

Alternatives to On-the-Ground Reporting

Pete Pattisson regularly covers forced labor and human rights in the GCC for The Guardian (UK).

“Reporting on migrant workers in the Gulf is difficult at the best of times, but COVID-19 has made it more challenging — and more important — than ever. There is no substitute for on-the-ground reporting, but the coronavirus has made it much harder, if not impossible. So what are the alternatives?

“One option is to use your sources in the migrant worker community to arrange phone or online interviews. If you’ve been working in the region for some time, you will have a network of contacts to draw on. If not, reach out to NGOs working in the region, like

Migrant-Rights.org.

“You can also contact migrant workers directly through social media, but this comes with challenges. How do you convince strangers to trust you, especially in a part of the world where it is risky to speak out? And how do you trust them and verify what they tell you? One obvious answer is to talk to as many people as possible. When you do that, the key issues begin to appear quite quickly. It is also possible to learn about the current situation in the Gulf by talking to migrant workers who have recently returned home. They may be easier to reach and more willing to talk.”

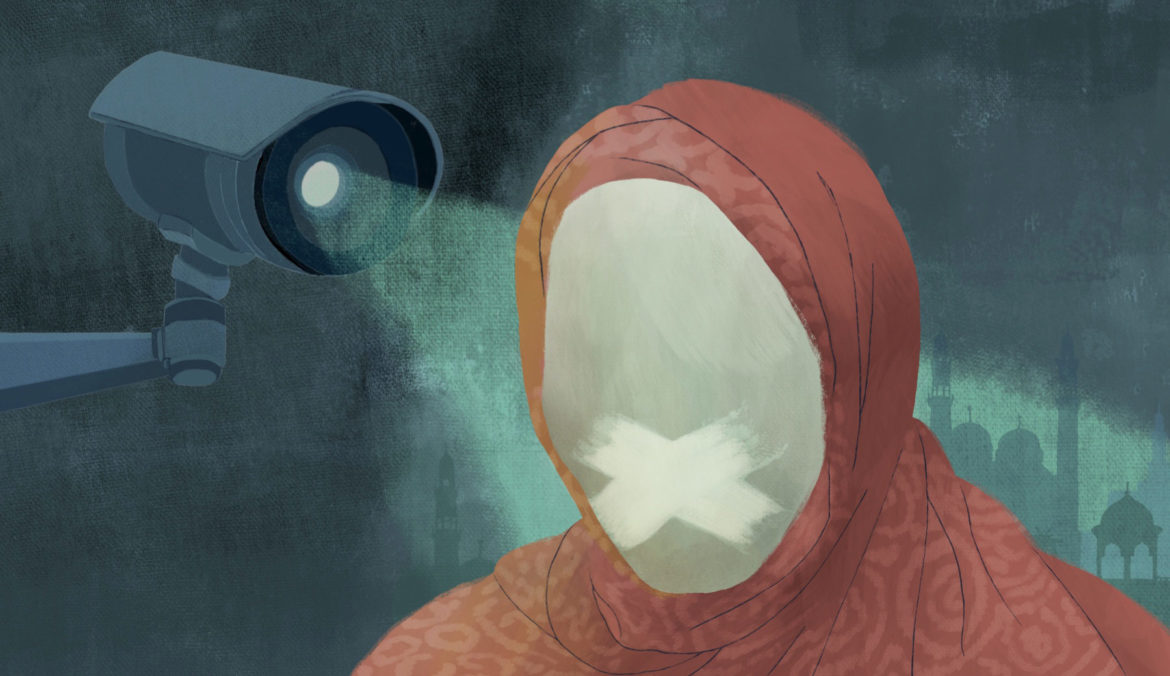

Protecting Sources, Reporting as a Woman

Rabiya Jaffery is a Gulf-based freelance journalist.

“The most common challenge I have faced covering stories on forced labor in the Gulf (mainly Saudi Arabia and the UAE) has been being able to report in a credible way that also protects the anonymity of the sources. Most of the people I speak to are, understandably, unwilling to speak with their identities revealed on the record because they are afraid of the legal repercussions. Publications that have a more nuanced understanding of the region are happy to keep sources anonymous, but I know of a few major international publications that are hesitant to do this and I have often had to kill potentially important stories because I know that naming the sources could endanger them.

“Also, being a woman means that a lot of spaces (construction sites, male labor residences, even some offices) are completely inaccessible to me — especially in Saudi Arabia — and in those situations I have had to get help from a male fixer to be my eyes on the ground. Alternatively, however, being a woman provides me access to some spaces that men cannot enter so I guess it balances out.

“Ethically, I struggle with not reporting stories that I know of and that are important, but because the corrupt institution in question is the government/state, I often have to ignore the story entirely because I know reporting it can get me in very serious trouble.”

Pushing Back Against a False Narrative

Rejimon Kuttappan is a special correspondent for The Lede. He writes extensively on migration for various publications in the region and in India. He used to live and work in Oman, before being banned from the country for reporting on migrant issues.

“Reporting migrant workers’ stories in the Arab Gulf during the pandemic outbreak was a real challenge I faced during my decade-long journalism career. The COVID-19 outbreak and pandemic-induced economic crisis forced migrant workers into some of the most miserable conditions in a century.

“I managed to tell some 40 stories between March and July 2020 about migrant workers in the Arab Gulf who were left in the lurch. Even when the migrant workers managed to tell their stories to me, I was struggling to write balanced reports as their employers, the host countries, the sending countries, and global watchdog groups were reluctant to talk to me. Additionally, the need to tell these stories in a timely manner provided added pressure.

“Most of the stakeholders in the migration workers’ story wanted to portray an ‘all is well’ picture. Even when they were failing, they were not open to talking to the media.

“Those in India were either unable to see the real picture or were deliberately ignorant, alleging that I was exaggerating the situation. I received personal threats over phone, email, and social media for reporting the inconvenient truth. A few even alleged that I was trying to destabilize the good relations between India and the Arab Gulf, and that I was lying even when I had on-the-record quotes.”

Persevering amid an Information Crackdown

Anonymous journalist based in the GCC with an international wire service, who fears reprisals from governments in the region if named.

“At first, access to information was more difficult (due to the COVID-19 pandemic), then there was a shift and Gulf governments really wanted to get their message out, so there was more openness and access. Early on, press conferences from GCC health authorities were closed to international media (this is a common occurrence for us on other topics too) and only the local press was invited to attend. But then, as cases rose, all press conferences were closed to all media for safety reasons.

“As part of the information crackdown, Gulf governments conducted more public relations events (sending of medical aid to various countries, visits to new field hospitals or ventilator factories, etc.). However, even these staged moments had some use to us, since they allowed the press to obtain images and some context besides just daily case statistics.

“COVID-19 affected coverage of other subjects and made them more difficult to cover as well. Without events or press conferences to attend and no possibility of in-person meetings because of the restrictions in place, it became harder to get insights into what was going on on the ground and we had to rely more on digital/electronic communications with contacts and sources.”