Despite increasing state-control, violence against journalists and other threats to press freedom, Southeast Asian journalists are increasingly delving into data journalism and other forms of innovative storytelling and creating a greater impact than ever before. Among those making a key contribution is a Malaysian data journalist named Kuang Keng Kuek Ser.

Kuang Keng at a recent journalism conference.

Kuang Keng has spent the last decade working to build data journalism in Southeast Asia. After graduating with a chemical engineering degree, he began his career in 2005 at GIJN’s member in Malaysia, the independent news website Malaysiakini. As one of the very few journalists in the newsroom with a science background, he got involved with a lot of data crunching, particularly around political issues and elections. Fast-forward eight years: Kuang Keng received a Fulbright Scholarship to pursue a master’s degree on media innovation at New York University, followed by a Tow-Knight Center fellowship. This enabled him to work further on his core focus: designing data journalism training programs for newsroom.

In 2015, Kuang Keng launched Data-N, which has since trained hundreds of journalists in Southeast Asia.

It wasn’t an easy start in a region where data journalism was nearly non-existent. Data-N began by providing free training courses and expanding its network into the region’s newsrooms and journalism conferences to get the word out. Slowly, Kuang Keng got not only journalists — but, key to the sustainability of data journalism projects, entire newsrooms — interested in data journalism. His workshops now reach into countries like Nepal, India, Indonesia and Singapore, with some initiatives developing into ongoing projects where Data-N works hand in-hand-with the newsrooms.

In an interview with GIJN Chinese editor Siran Liang, Kuang Keng talked about the rise of data journalism in Southeast Asia.

What are the difficulties journalists in this region face when attempting to do data journalism?

The first is the accessibility to data — which is what data journalists around the world know — especially government data. Even you have access to data, a lot of times the quality is not there. So you need a lot of double verification, cleaning and asking a lot of questions to authorities to find out about the real state or quality of the data.

Also, a lot of people think that internet access in this region is very good. But this is only true in certain countries and certain cities. In many places, such as Malaysia, Indonesia, Philippines, India and Nepal, they don’t have very good internet speed. So if you recommend doing a data-visualized story, that would require more speed and it might not work for the audience. They are looking for something light and fast. So an image or GIF is better than a JavaScript.

Another real challenge is that it’s very hard to find talented journalists with statistical knowledge or computer science backgrounds. There are very good programmers and coders here but if you are talking about journalists who can also do data and programming, it’s very rare.

Has the field changed a lot since you first got into the profession?

When you talked about data journalism four or five years ago, people might have been wondering what you are saying. Now they know exactly what it is and you get their attention. There’s a very strong desire among journalists and newsrooms to do data. The question they are facing now is actually what kind of resources they need to invest in and what kind of people that they need to train or hire to do data journalism.

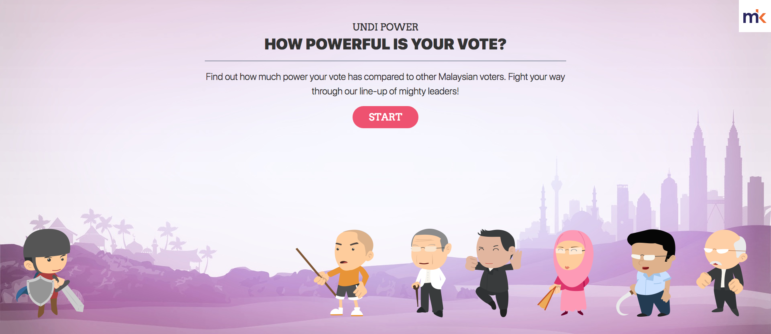

Collaboration: Data-N worked with Malaysiakini to produce Undi Power, an interactive news game that helps users to understand more about the Malaysian electoral system. Screenshot

How much are newsrooms investing or are willing to invest in this?

They have a strong desire but that doesn’t translate into real investment. They are putting a lot of resources into social media and video journalism, believing that video is the next thing in journalism. Social media and video journalism give you very clear metrics you can track and monetize them almost immediately. When it comes to data journalism, they are not sure how much should be put in as it is not very clear to them what the returns are.

What can journalists do if newsrooms are not willing to invest in data journalism? Is training enough?

That is the problem we are facing now. When I first developed Data-N, I told my participants that just attending the workshop is never enough — nothing will change in your newsroom. When people go back to their newsroom to try new things based on what they’ve learned from the workshop, they don’t get support from their colleagues, bosses or editors.

That’s why I engage with newsrooms, trying to learn how they operate, what kind of reporting they are doing, what kind of tools they have and what things they really want to produce after the training. The post-training job is to make sure I always follow up.

In the future I would like to have more long-term collaborations. Last year, I did a six-month mentorship, a collaboration with 4M Asia, a media program funded by the French government to help media in Southeast Asia develop storytelling skills. We had three workshops, in Phnom Penh, Kuala Lumpur and Manila. We asked newsrooms to submit data story proposals and selected 12 newsrooms from about 40 proposals from the region. In between workshops we gave them support through a Slack group. Many of them eventually published the projects they proposed and some of the projects were shortlisted for the Data Journalism Awards. That’s actually a better model of training.

Is this model sustainable?

Not really, because you need a lot of money. What I’m looking at now is to work with newsrooms that have formed a team of two or three people and want to get help to train and mentor them on data journalism project ideas.

I had one project with Malaysiakini last year where I collaborated with their journalists, designers and programmers and we produced a news game on elections based on data, which was also shortlisted for the Data Journalism Awards. The bigger impact is that the newsroom really started to look at data journalism more seriously and they are planning for more data journalism projects.

Besides the projects developed in those workshops, have there been other notable, innovative projects in the region?

I always recommend a few websites. One is Katadata from Indonesia. It is a media company that does data stories as well as providing data services to other publications, and even the government. One time they produced a physical infographic exhibition in a shopping mall about the history of economic development of Indonesia. The president came to officiate the exhibition.

Several other publications which are using data in their reporting include Tempo and Kompas (Editor’s note: previously named Compass, Indonesia’s national newspaper), which won a hackathon held by the Global Editors Network in Jarkata early this year.

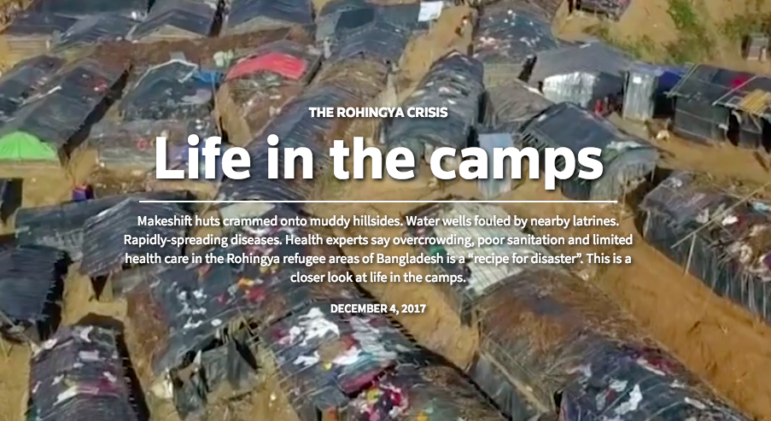

Reuters on Rohingya: The Reuters graphic team, based in Singapore, won a Data Journalism Award for their piece on the refugee crisis in Bangladesh. Screenshot

In Singapore, The Straits Times, the largest newspaper, started to do some stories with data. Recently they published a very good interactive explainer of the Malaysian election.

There is also a lot of good work coming from the graphic team at Reuters which is based in Singapore and is mostly made up of Singaporean journalists. One of the stories that won the Data Journalism Awards was about the Rohingya camp in Bangladesh.

There’s also Rappler in the Philippines, which is doing very great work on data and social media as well.

Then there’s the Center for Investigative Journalism Nepal. They have been doing some data journalism and journalist Arun Karki has been advocating and helping in the training of data journalism.

It seems that a lot of progress in this region depends on individual pioneers or advocates. Are there any examples of collaborations between newsrooms or individuals?

Data journalists in this region know each other because there are not many of us. We talk to each other, share resources, network and sometimes we collaborate.

For example, when CIJ Nepal invited me to do training for their journalists, Arun was there to help me with training. When Nepali journalists do investigations that involve Malaysian companies, as there is a lot of business going on between Nepal and Malaysia, Arun and I will connect the Nepali and Malaysian journalists so they can collaborate.

How do you think data journalism will develop in this region in the next few years?

Southeast Asia is very good at playing catch up. For example, when the West was still using laptops, Southeast Asia was already overtaking them, jumping from desktops straight to smartphones. We became one of the world’s largest markets for social media and video, and I expect in a few years you will see a lot more data journalism projects and interactive storytelling coming out of this region.

Of course, the fundamental problem that will not change quickly is the data quality. That is outside of the control of the media industry. In this region we still have many strong governments that have been in power for years.

Also, the crisis faced by media industries when compared to the West is a little bit different here. We have big media companies that are making money, even today. Then you have media companies in emerging economies like Vietnam and Myanmar. They have just opened up and people have begun to have access to the internet, where they consume more news content. Those are huge markets compared to the mature markets in the West where they are losing money and closing down newsrooms. We still have resources to put into innovation. What we need to solve is the issue of nurturing talent and awareness.

Any suggestions for young journalists who are working and considering to work in data journalism?

When you pick up skills in data journalism, work on real projects, and when designing a data journalism project, consider user experience, user interface and content distribution. Second is to make sure you know how to pitch your idea — even if you have very good skills, you need to be able to convince your boss to give you the resources and time you need to deliver your project. The third thing is, if you receive training in the West, come back to this region. It has a lot more opportunities.

Siran Liang is the editor for GIJN in Chinese. She has a master’s in journalism and media studies from the University of Hong Kong. Before joining GIJN, she was an intern with the Nepali Times, where she covered the country’s reconstruction after the 2015 earthquake, as well as the blockade by India.

Siran Liang is the editor for GIJN in Chinese. She has a master’s in journalism and media studies from the University of Hong Kong. Before joining GIJN, she was an intern with the Nepali Times, where she covered the country’s reconstruction after the 2015 earthquake, as well as the blockade by India.