On File: Troves of documents can be found by those looking in the right places. Photo: Samuel Zeller on Unsplash

Some of the world’s secrets are open, just waiting to be unearthed by keen journalists.

For example, an Australian company negotiated shares worth millions of dollars with the family of the president of the Republic of Congo to get a mining permit. A Cameroonian minister of mines allocated a permit to a company in which his wife had shares. The World Bank gave $19m to a company with links to Liberia’s Charles Taylor, convicted for crimes against humanity.

These stories, and many more, come from open-source documents. They were just waiting for a journalist to read them, sitting in some dank government building or maybe published on the internet.

Here’s a few tips to help you find your own open-source secrets.

1. Look for the Story

The main hurdle separating journalists from a multitude of such secrets is the belief that to break a big story you’ll need to get leaked documents, maybe wear a moustache and a wig or have lots money. That’s really not true.

For example, in Cameroon, we obtained incorporation documents that showed that a mining minister’s wife had shares in the company that benefited from a very valuable permit allocated by her husband. The wife’s name was plainly written in the documents and all that we needed to do was bit of googling and make a phone call (asking to talk to her husband) to confirm they were indeed married.

We got the documents from Cameroon’s official company register quite easily. Sure, we didn’t turn up and explain that we wanted to expose corruption in a mining project, but we got the documents the official way – going through the archives of the Tribunal of Commerce in Yaoundé. In the Democratic Republic of Congo, Bloomberg did a huge story on president Kabila’s business interests — all of this was public information, much of it available online.

I am convinced there are hundreds of stories waiting in business registries around the world, and that’s just one example of open source documents.

2. Start at Home and then Go Abroad

Although the most valuable documents are often in-country, sometimes it’s also good to look elsewhere, and that usually doesn’t require travel.

For example, any company listed on a stock exchange will have to provide lots of information online. The same applies to information on companies and organizations funded by aid money, such as by the World Bank’s International Finance Corporation. You can also request specific documents from those organizations via their press contact, or through Freedom of Information requests.

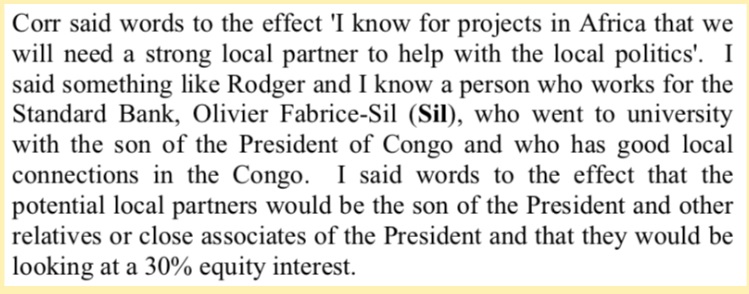

Another example of a great open-source information is court cases. People who go at each other’s throat in a tribunal don’t always think someone else will take an interest in their case. For example, I found out in a Supreme Court judgment that an Australian mining company had given shares to the family of Congo’s president. I didn’t need to dig very deep, because when you find something like this, you know it’s going to be interesting:

This was the same company in which Cameroon’s mining minister’s wife was involved. When you find an organization whose operations are questionable in one country, you can follow its actions elsewhere and harvest more stories.

3. Be Stubborn and Know the Laws

Some African countries, like Liberia or Sierra Leone, have Freedom of Information laws that enable citizens to request specific documents from their government. Each country will have different rules on the documents that are publicly available, so you just need to think what documents you need, and make your best attempt at getting them.

It usually pays to be very, very stubborn and know the rules to access the documents. For example, getting company incorporation documents in Liberia was quite quick, but in Cameroon it took a few weeks. It wasn’t because they didn’t want to give us the documents, it was because their archives looked like this:

Piles of Files: The state of the archives at the Tribunal of Commerce in Yaoundé. Photo: Perrine Odier

Sometimes it’s not easy to actually obtain the documents that you should get by law. In the worse case, if you’re refused access, you could also write a story about that.

4. Use Your Local Knowledge to Sift Through Information

There’s a lot of open-source materials out there — literally more than the whole internet. So the challenge isn’t so much to find documents, it’s to dig something interesting out of them.

That’s where your own knowledge is invaluable. You need to know what to search for: people’s names, companies, fishy projects, etc. Without knowing the names of a country’s powerful players, or which companies are shady, you won’t recognize a lead when you see it. You can also use tipoffs, which might initially just be unpublishable rumors, to target your research.

There’s already a lot written about the multitude of tools that can enable you to search for information online.

Sometimes the sheer amount of online research tools can be a bit overwhelming. So, here’s my personal shortlist to look a name up: I usually start by searching it on Google, then www.opencorporates.com, followed by https://data.occrp.org, and finally https://offshoreleaks.icij.org (here are some tips on using it). Once you find something interesting, don’t forget to save it!

There are lots of little tricks that you can learn with each of those tools, such as filtering by publication date on Google, or using quotation marks to look for a specific name in search engines from Google to ICIJ’s offshore database. Each journalist will come up with their own recipes.

5. Finally: Cross-check Your Sources

Documents seldom lie, but because it’s written, it doesn’t mean it’s true. You’ll need to verify your open sources like you would check human sources.

Think about: Could the documents be falsified? Where did you get them? Was it on an official government website or on a Facebook group? Are there any other sources that can confirm the information? Is your document about the correct person or a homonym? Have you got comments from the people you’re accusing?

For more information: Find more on FOIA laws in GIJN’s Global Guide on Using FOIA, with links to African and worldwide resources.

Emmanuel Freudenthal is a freelance investigative journalist and photographer who covers East and Central Africa, with a particular focus on business, corruption, natural resources, land and human rights. He also trains journalists in investigative methods for the Thomson Reuters Foundation.

Emmanuel Freudenthal is a freelance investigative journalist and photographer who covers East and Central Africa, with a particular focus on business, corruption, natural resources, land and human rights. He also trains journalists in investigative methods for the Thomson Reuters Foundation.