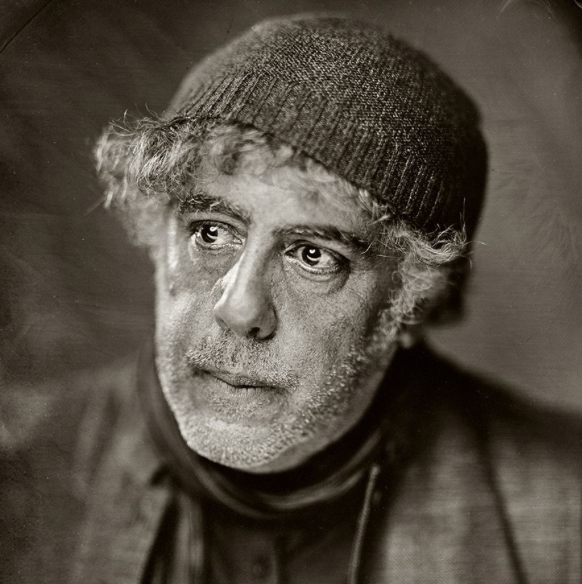

Harush Ziberi, a Muslim man, begs for his life from the Serbian paramilitary unit known as the Tigers during the first battle of the war in Bosnia in 1992. He was later thrown from a window during an interrogation and eventually found dead in a mass grave. Image: Courtesy of Ron Haviv, VII

Editor’s Note: This post is the second installment from GIJN’s Reporter’s Guide to Investigating War Crimes. The first part of the series, on open source research, has already been published. The guide will be released in full this September at the Global Investigative Journalism Conference. The end of this chapter also features a Special Focus interview by Olivier Holmey with visual investigations journalist Azmat Khan, on The New York Times exposé on civilian casualties from US drone strikes.

Journalists are key witnesses to atrocities committed against civilians. Without their eyes and presence on the ground, the barbarity of wars would probably go unnoticed.

Nailing down who did what to whom, where, when, and how are the basic questions journalists would naturally ask. This is true whether one is covering international armed conflicts where more than one state is involved, or non-international conflicts like civil wars, which can both result in deaths or injuries of civilians, displacement, and destruction of infrastructure or medical facilities.

Hindering humanitarian aid, either by looting or blocking access to affected areas, and misinformation campaigns — which impact people’s abilities to make sound judgments, putting their lives at risk — can also cause great suffering to civilians.

Nevertheless, it’s important to understand that, in war, acts that cause harm to civilians or their property are not always unlawful. In order to understand whether or not a war crime or other violation of international law may have been committed against civilians, it will be necessary to establish as much detail as possible about the context and circumstances. The obligation on parties to a conflict to distinguish at all times between civilians and combatants is one of the most fundamental rules of international humanitarian law (also known as the laws of armed conflict or the laws of war). While purposefully targeting civilians or civilian objects does constitute a war crime, civilian harm resulting from attacks is not necessarily unlawful if it respects the principle of proportionality.

Violating either of the principles of proportionality or distinction constitutes a war crime. Some other specific war crimes against civilians include (but are not limited to):

- Torture or inhuman treatment

- Unlawful deportation or transfer or unlawful confinement

- Taking of hostages

- Transfer of civilian population into occupied territory, or deportation of the population of the occupied territory

- Pillaging

- Use of prohibited weapons

- Rape and other sexual violence

- Use of human shields

- Using starvation as a method of warfare

- Recruiting child soldiers

In some cases, for example sexual violence or torture, it will be more obvious that these are unlawful acts, as such acts are always prohibited, even against combatants. However, when coming across the scene of possible unlawful attacks against civilians or civilian property or infrastructure, some of the questions that will need to be asked include:

- Was the victim a civilian? Were they possibly taking a direct part in hostilities?

- Was the property or infrastructure destroyed a civilian or military objective? (Did it have a possible military use?)

- Were these people/property the target of the attack? Or was the harm a consequence of targeting something or someone else (e.g., was there a military objective or combatant nearby?)

Even with this information it may not always be possible to determine the legality of an act, but answering these questions can begin pointing towards the answers.

Ukrainians flee as the Russian military advances into Irpin, Ukraine, 2022. Image: Courtesy of Ron Haviv, VII

Tips and Tools

Before embarking on this journey of fact-finding, investigating, and collecting evidence, journalists need a deep understanding of the facts. There is nothing more important than being fully informed about the geography and landscape, the population under attack, the perpetrators, the political, cultural and religious dynamics, the historical background of the conflict, and how it has unfolded.

Background Research

Such extensive research is required before conducting deep, months-long investigations into attacks against civilians in order to protect journalists from being manipulated by misleading narratives and propaganda. It can also boost confidence before a journalist even sets foot in the conflict zone.

One of the main sources of research are think tanks, like those on this George Washington University list of top think tanks in the Middle East and North Africa. Research centers like the International Crisis Group, in addition to the UN Panel of Experts, and rights groups like Amnesty International are always informative. Previous work done by UN human rights investigators is also important, such as those affiliated with the Office of the High Commission of Human Rights.

As always, journalists should do a full search of previous work on the conflict. A look at a news database like LexisNexis can help identify the best investigations.

This initial research should arm a reporter with a list of questions: about the movers and shakers, profiteers, external and internal forces, front lines, composition of the impacted populations, resources at stake, and more. This will give journalists guidance on which experts to seek out. Journalists not only need experts’ insights but also their unanswered questions, which may provide new leads in one’s own research.

More than 600 Rohingya refugees on makeshift rafts cross the Naf River fleeing Myanmar to arrive at Shah Porir Dwip Island, Bangladesh. Image: Courtesy of Ron Haviv; John Stanmeyer, VII

Interviews with Witnesses and Victims

In order to prove victims are civilians, journalists need to look for documents that verify identity, and records that show educational background and career history. Journalists can also collect testimonies from local municipal officials, tribal leaders, and neighbors. The families of the victims may keep copies of documents such as graduation certificates, or invoices or receipts that show payment of salaries (if employees) or the source of income (if running private businesses) around the same time as the attack. The collection of such evidence or testimony, along with the corresponding paper trail, should give enough answers to whether the victim was part of the conflict.

As for whether properties that came under attack were for civilian use, parties of the conflict (especially if involving legitimate or government entities) should have what is known as a “no-target” list, which includes all civilian properties that participants in the war must avoid. Journalists documenting war crimes should reach out to sources at the ministries of defense, sometimes to the relevant UN bodies, and other international organizations to obtain a copy of this list in order to check and compare what came under attack and establish without doubt which sites had no military value.

In some situations, properties on the no-target list can be occupied or taken over by parties of the conflict, similar to soldiers or fighters using human shields. In those situations, witness accounts, especially those living in the same vicinity, are key to establishing whether military forces were present at the site during the time of the attack. On many occasions, civilians may possess footage of suspicious activity in buildings near them. It’s worth asking neighbors if they have any visual evidence of whether armed groups are using nearby buildings for military purposes.

Interviews with Former Combatants or Insiders

In other situations, gaining insights from insiders who are former members of armed groups or defectors could also serve as additional evidence. Speaking to these insiders — those connected to, or with direct knowledge of, any of the parties of the conflict — should be a top priority of any investigation. However, investigators must be wary of approaching insiders and always consider: What is the motive this source has for coming forward with information?

Also recognize that there are different types of insiders: Those forced to join perpetrators against their will; those who believe that the benefits of cooperating outweighs the harm; and those who freely joined the perpetrators, and later repented.

Questions to these insiders could include: What was the motive or intent behind an attack or certain act? For example, were they targeting a specific combatant or military objective in the area or were they intending to target civilians and their property? It is also helpful to try and establish what information the parties to the conflict had at the time of the attack, such as the intelligence about the nature of the buildings or the presence of combatants in the areas. Were they aware of the presence of civilian buildings or people? Both of these elements — intent and information available to the parties — are crucial to establishing the legality of certain acts in armed conflict. They can help to point towards establishing — or disproving — war crimes against civilians.

Breaching the Language Barrier

Language can be a major barrier for journalists working internationally. It’s essential to give time, effort, and if possible a special budget to find a reliable, independent, and previously tested interpreter Also important: a backup, such as a colleague or an independent researcher who can cross-reference your translations. Interpreters’ impartiality is something journalists must not overlook. As many journalists do, asking one question several times in different ways provides a way to verify the accuracy of a translation.

Preparing for Traumatic Conversations

The cornerstone of any investigation into human costs of war is civilian testimony. Be prepared, as these civilians may be seriously impacted by the death of a family member, injury, various assaults including rape, psychological trauma, displacement, or loss of property. Journalists might get overwhelmed by the task of sitting with shattered souls to get their accounts for fear of retraumatizing them.

Victims or witnesses often open up only after a second or a third interview. And while journalists need to collect as much testimony as possible, conducting several interviews with one person may be difficult. However, journalists can also do initial interviews with victims to determine which ones would be the most important because they are direct witnesses, most affected, or have relatives or friends who support opposing forces in the conflict and who can provide more inside information about the attacks themselves.

Keeping a written timeline also helps journalists to understand the sequence of events and will lead to further questions which can fill in the gaps of information. Collecting names, contacts, and pictures of the interviewees is essential.

A counselor, Sifa Muhima, 47, (right) speaks with a rape victim at a “maison d’écoute,” also known as a listening house, in the Democratic Republic of Congo. These houses provide victims immediate medical care and support counseling after being raped. Image: Courtesy of Ron Haviv, VII

Cellphones are Gold Mines

Cellphones are a treasure of data for journalists, and getting access to a victim or witness’s phone can be indispensable. Once victims start to open up and share their stories, journalists should always ask them to “show me” whatever can support the victims’ account. Chats on social media platforms, such as WhatsApp or Telegram, can show last moments of conversations before an attack. They can also provide a definitive answer with whom the victim was communicating, the content of any discussions, movement, actions, and other factors that would indicate a victim’s status in the armed conflict around the same time of the attack.

In addition, journalists can ask victims to consent to share screenshots, pictures, or videos from their phones, including contacts of other victims, or sources who might have inside information or documents needed for the investigation. It’s important to check dates, locations, and to ask questions about the context of the photos so that they can later be cross-checked with locations and dates gathered during the course of the investigation. Reporters always need to carry copies of written consent forms for owners of the material to give journalists’ permission to publish.

Collecting Physical Evidence and Military Materiel

As many rights activists and experts have done in past decades, collecting shrapnel, spent ordnance, or other evidence of weapons and armaments are a crucial element in verifying the basic information about an attack. Marks or writings on this battlefield detritus can be examined by experts to determine the origins.

This kind of evidence paves the way for future investigation into the countries that exported the weapons to the attacking party. In addition to victims and insiders, look for accounts from other sources: medical teams, relief workers, lawyers, tribal leaders, local officials, drivers, and school teachers, all of whom can add depth and open up pathways for further investigations.

Getting coordinates, locations, maps, and accurate descriptions of the sites of attacks on civilians are important for seeking verification and documentation through satellite imagery or other geolocation techniques.

Case Studies

US Drone Strikes Killing Yemeni Civilians

What does it take to prove that a victim of a US drone strike is a civilian, and not an al-Qaida militant? Hundreds of documents, pictures, chat messages, and IDs.

This is what the Associated Press team collected in Yemen in 2018 to disprove US claims that its airstrikes had only killed al-Qaida militants in the region. AP’s Pulitzer Prize-winning investigation, in fact, found that roughly one-third of all deaths in that year’s drone campaign were civilians.

A months-long AP investigation in 2018 debunked US military claims that its drone airstrikes had only killed al-Qaida militants in Yemen. Instead, the AP found one-third of all airstrike victims were civilians. Image: Screenshot, Associated Press

The months-long investigation drew upon open source data from groups such as The Bureau of Investigative Journalism and Amnesty International, and from lists of US airstrikes in Yemen provided to the AP by the Pentagon.

However, none of the sources indicated the extent of the civilian casualties, nor that the casualties occurred in the context of international pressure on the Saudi-led coalition, which was waging a bloody war against Iranian-backed Houthi rebels. News about US drone strikes was almost nonexistent and the international media attention focused exclusively on Saudi atrocities.

The investigation covered a large geographical area across southern, eastern, and central Yemen where al-Qaida was active and where the drones were flying overhead.

The first step involved collecting all of the dates and locations of the strikes provided by a Pentagon source. Then all incidents were checked, a list was compiled of strike sites, and local human rights activists, doctors, tribal leaders, security, and government officials in the targeted areas were identified.

The third step was conducting thorough interviews with people close to the victims to piece together their profiles to prove they lived civilian lives and had no record of terrorism. The interviews aimed at answering key questions such as: the proximity of the victims to the site of the strike, why the victim was at that specific location, who else witnessed the strike, was there any indication or sign that al-Qaida militants were nearby.

Families of the victims have called upon human rights groups and the International Committee of the Red Cross to further investigate these drone strikes, to no avail.

Myanmar Military’s Ethnic Violence Against the Rohingya

In a powerful investigation published in February 2018, Reuters exposed ethnic violence and massacres of Rohingya in its story How Myanmar Forces Burned, Looted, and Killed in a Remote Village. The piece won the Pulitzer Prize for international reporting in 2019, and resulted in two Reuters reporters being arrested and jailed. (The pair were ultimately freed in 2019 after spending more than 500 days in prison.)

The investigation focused on a single village in northern Rakhine state targeted by ethnic violence. It was the first time the massacre was pieced together from accounts of perpetrators. In previous coverage of the Myanmar genocide, only victims had spoken about the crimes committed against the Rohingya minority.

Notably, Reuters got sources with inside information to speak with them. Buddhist villagers, members of the paramilitary police, and security personnel who participated in the killings all spoke to reporters. Using photos of the massacre itself, Reuters was able to obtain indisputable evidence of the event.

The story noted that three photos provided by a Buddhist villager “capture key moments in the massacre at Inn Din, from the Rohingya men’s detention by soldiers in the early evening of Sept. 1 to their execution shortly after 10 AM on Sept. 2.” Other photos showed captives lined up in a row and men’s bodies in a grave.

Visiting the site of the massacre, taking pictures there, and showing them to forensic experts were also key elements of the investigation. The experts all “observed human remains.”

The Myanmar military told Reuters that its “clearance operation” in the region were legitimate, but the story noted “the United Nations has said the army may have committed genocide; the United States has called the action ethnic cleansing.”

Russian Siege of Ukraine’s Mariupol

In its eye-opening visual documentation of the Russian siege titled 20 Days in Mariupol, an Associated Press team was the only international media left in the Ukrainian city in mid-March 2022. It spent weeks exposing Russian attacks on civilians that have been alleged as war crimes, after invading forces cut off the city from the outside world, effectively imposing a media blackout. After nearly three weeks in the besieged city, the AP team had to be rushed out of Mariupol, upon learning that Russian soldiers were reportedly targeting them.

The AP’s important work also exposed the Russian government’s disinformation campaigns by providing a first-hand account of the attacks committed against civilians. Shocking AP footage of a maternity hospital under assault — and a pregnant woman rushing out from the building — prompted the Russian embassy in London to try to dismiss the shocking photos as fake. To counter the propaganda, AP reporters went back and found the woman and proved she was pregnant as she gave birth to her baby.

“With no information coming out of a city, no pictures of demolished buildings and dying children, the Russian forces could do whatever they wanted. If not for us, there would be nothing,” said Mstyslav Chernov, the AP videographer who, with his colleagues, won a Sundance Audience Award after their reporting was turned into a 90-minute documentary. “I have never, ever felt that breaking the silence was so important,” he added.

Killing of a Palestinian-American Journalist

After the shooting death of Palestinian-American Al Jazeera correspondent Shireen Abu Akleh in the West Bank, several media organizations launched investigations to understand what really happened.

The New York Times was among the media organizations that went beyond gathering official statements and testimonies of witnesses, including Abu Akleh’s colleagues who were at the site of the shooting. Notably, the team also conducted detailed forensic examinations of user-generated videos posted on TikTok and other social media to look for clues to reconstruct what happened.

The Times concluded that Abu Akleh was killed by a bullet fired from the same location as an Israeli convoy that was raiding a nearby refugee camp in Jenin at the same time. “Most likely by a soldier from an elite unit,” the investigation found.

The investigation also ruled out the theory, initially promoted by Israeli officials, that Palestinian gunmen were behind the shooting, based on the distance and positioning between the gunmen and Abu Akleh’s location.

One of the most important tools used by the Times was audio analysis of the sound of the gunfire recorded in these user-generated videos. “Measuring the microseconds between the sound of each bullet leaving the gun barrel and the time it passed the cameras’ microphones, they were able to calculate the distance between the gun and the microphones,” the Times explained. “They also considered the air temperature that morning and the type of the bullet most commonly used by both the Israelis and the Palestinians.”

Special Focus: Civilian Casualties from US Military Drone Attacks

Interview of Azmat Khan, by Olivier Holmey

When, in early 2018, Azmat Khan visited western Mosul in Iraq, the destruction was so extensive that all the residents had moved away – and the reporter found few people to interview. Only on subsequent visits, once some of the population had returned, was Khan able to collect testimonies that helped establish that drone attacks had killed civilians in the area in greater numbers than what the US-led coalition fighting Islamic State (ISIS) had claimed.

Azmat Khan, a Pulitzer-Prize winning member of The New York Time visual investigations team. Image: Courtesy of Khan

Khan has led extensive investigations into the civilian casualties of US remote warfare in Iraq, Syria and Afghanistan – most notably for two New York Times reports, The Uncounted and The Civilian Casualty Files. On-the-ground reporting is at the heart of her work – and it typically requires multiple visits.

Khan has also relied on classified US military files and open-source reporting tools. “We can do some things from a distance,” she says, “but it is my view that going on the ground allows you to reach a higher bar of investigation. All too often, reporting from a distance can flatten people.”

To make sure those she encounters answer her questions as candidly as possible, Khan says that she does not give advance notice of her visits. She also avoids asking leading questions. On one occasion, an eyewitness spontaneously brought up the fact that a man in a wheelchair was in a house that was struck, which matched a piece of information that had come up during her research, thereby confirming his reliability as an interviewee.

Khan has relied on a variety of sources – some of them unlikely ones. She says that ISIS propaganda videos turned out to be surprisingly reliable when it came to footage of civilian casualties. Meanwhile, the US government’s own YouTube posts about coalition airstrikes helped her date and geolocate attacks that the US was simultaneously denying. In Iraq, she was able to consult death certificates to confirm casualties. But in remote parts of Afghanistan, she found that she had to study tombstones instead, as official death notices were not available.

Determining who counts as a civilian among the casualties can be tricky, she notes. Her own definition did not include the family members of ISIS fighters – a decision she made because she was not able to gather information about those individuals, but which she acknowledges likely means that she undercounted civilian casualties.

Additional Resources

Reporter’s Guide to Investigating War Crimes: Open Source Research

How the NYT’s Pulitzer-Winning Series Exposed Civilian Deaths in the Air War on ISIS

Lessons Learned from Syrian Journalists Investigating Russian War Crimes

Maggie Michael is an investigative journalist with Reuters based in Cairo. She has over 15 years of experience covering conflicts in the Middle East. In 2019, she was part of an Associated Press team that won various awards, including the Pulitzer Prize for international reporting and the McGill Medal for Courage for groundbreaking investigations of corruption, torture, and other war crimes in Yemen.

Maggie Michael is an investigative journalist with Reuters based in Cairo. She has over 15 years of experience covering conflicts in the Middle East. In 2019, she was part of an Associated Press team that won various awards, including the Pulitzer Prize for international reporting and the McGill Medal for Courage for groundbreaking investigations of corruption, torture, and other war crimes in Yemen.

Ron Haviv is an Emmy-nominated filmmaker, award-winning photojournalist, and co-founder of the photo agency VII, dedicated to documenting conflict and raising human rights issues around the globe. He is also the co-founder of the nonprofit VII Foundation, which concentrates on documentary projects and provides free visual journalism education.

Ron Haviv is an Emmy-nominated filmmaker, award-winning photojournalist, and co-founder of the photo agency VII, dedicated to documenting conflict and raising human rights issues around the globe. He is also the co-founder of the nonprofit VII Foundation, which concentrates on documentary projects and provides free visual journalism education.