Investigating on TikTok. Graphic: Courtesy of NRK

On March 4, less than 10 days into the Russian invasion of Ukraine, the Russian State Duma passed a law imposing jail sentences of up to 15 years for spreading “fake news” about the Russian military – one of many moves by the Kremlin to control the narrative on the war in Ukraine.

Almost overnight, Russian coverage of the war by independent news organizations became nearly impossible, with outlets such as Novaya Gazeta, one of the last bastions of investigative journalism in Russia, suspending their operations.

The Kremlin’s manipulation of the information war also included blocking social media sites such as Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter, the first two banned after a Russian court labeled their parent company, Meta, as “extremist.” Chinese-owned TikTok was one of the few social media platforms to avoid an all-out ban, thanks in part to a rule prohibiting new uploads and livestreaming inside Russia and the imposition of a digital block banning content from outside of the country.

TikTok, a looping video sharing platform mostly recognized for dancing and lip sync videos, has over one billion monthly users worldwide. Most adult users are in the United States, Indonesia, and Brazil, but the country with the fourth-most active users is Russia, with 51.3 million. (Douyin, which is how TikTok is branded in China, is reported to have another 600 million daily active users in that country.)

Though the site wasn’t closed down after the invasion, the content available on it has been severely restricted. According to Tracking Exposed, a European nonprofit that investigates the impact of social media platform algorithms, 95% of TikTok content previously available to Russian users was removed after March 7. As a result, US and European content, including information from official international organizations such as the UN, is no longer available to those inside Russia. Tracking Exposed found that, by April, Russian TikTok had been effectively transformed into state propaganda, with 93% of the site’s content about the invasion espousing pro-war views.

To more closely examine what the invasion looked like to TikTok users on the ground, and the differing digital narratives presented to users in Russia versus those inside Ukraine, a team of journalists from NRK, Norway’s public broadcasting company, launched an investigation.

On one side of the border, users saw cat videos, on the other, tanks and plumes of smoke from the conflict. Image: Courtesy of NRK

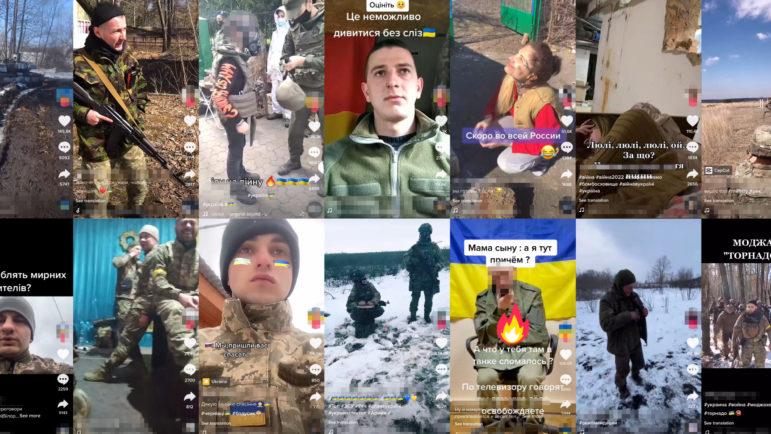

Through the use of two fictional avatar characters, NRK found that while Russian TikTok users were shown videos such as a dog petting a duck, on the Ukrainian side of the border, users saw videos showing smoke plumes from explosions, accounts from soldiers on the ground, and addresses from Ukraine’s wartime president.

GIJN interviewed Christian Nicolai Bjørke and Henrik Bøe, part of NRK’s 10-member investigative team, about their project, which illustrated how coverage of the war on TikTok is worlds apart for viewers in Ukraine and Russia.

GIJN: What was the initial concept for the story — did you base it on a hypothesis or a broader theme?

Christian Nicolai Bjørke: At the time, we were researching another project looking into TikTok algorithms, which had nothing to do with the war. So we thought — “Is there a way that we can apply the methods that we are now researching to another subject – maybe the war?”

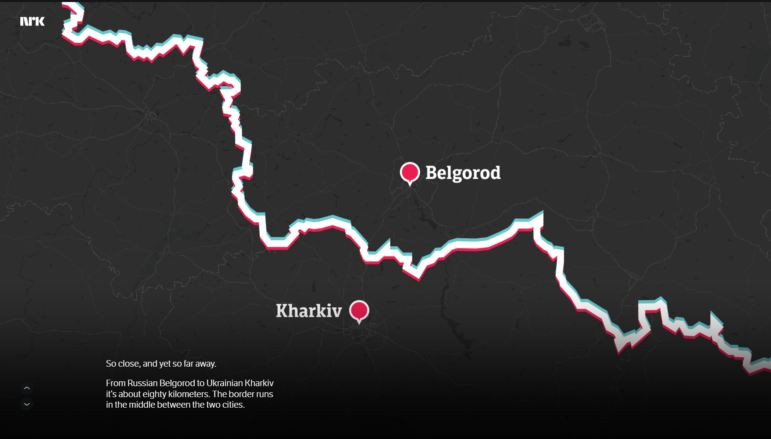

The idea came when we were looking at the map. At that time there was heavy fighting in Kharkiv and we saw that this city was close to the Russian city of Belgorod. The idea came in light of the discussion about Russian information freedom and to what extent Russian people had access to information, and of course the closing of major social media sites such as Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram. The thought struck us: Does a citizen in Kharkiv see the same videos on TikTok as someone in Belgorod, which lies only 80 kilometers (50 miles) away?

Henrik Bøe: We were inspired by a Wall Street Journal investigation into TikTok algorithms. They created bots [software applications programmed to complete certain tasks automatically] in 2021 to see what kind of rabbit hole they were sent down when programmed to watch videos with certain hashtags and topics for longer amounts of time. We wanted to do something similar. We already had an early functioning bot that could scroll through TikTok and we could program it to have different interests when the war started and that’s how this idea came about.

GIJN: How did you go about creating the bots?

HB: We created two TikTok accounts, using residential proxies to place our bots in specific cities — Kharkiv and Belgorod. We chose to create new TikTok accounts and we wanted these to be 19-year-old men because they are young, but still old enough to fight in the war.

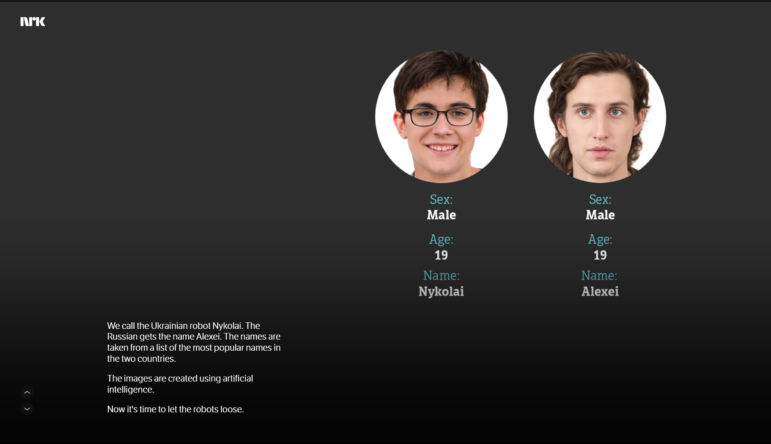

The avatars created by the journalists for the investigation. Alexei, on the right, was said to be in Belgorod, Russia, and Nykolai, on the left, in Kharkiv, Ukraine. Image: Screenshot

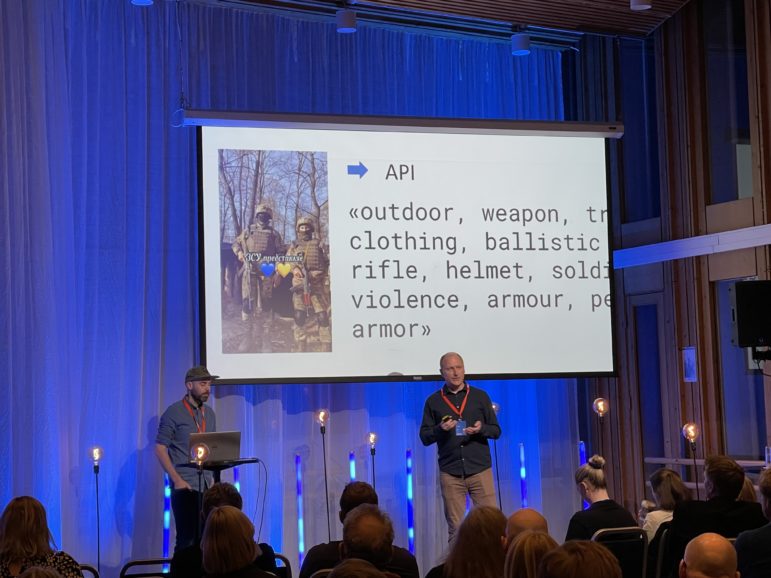

We used the programming language Python and the tool Selenium, which controls a web browser. It automatically scrolled through a web-based version of TikTok and then scraped all the data (i.e. text and cover image). We then used the Microsoft Azure Computer Vision API — to send the cover image there to get artificial intelligence to send back to us what it saw in the image, so that we could use those keywords as part of the determination of: “Is this a video about war or is it something else?” If it was about war, our bots would watch that video for a longer amount of time. However, in the very beginning, the first few hundred videos our bots scrolled through, they saw each video for about the same amount of time. We just wanted to see what TikTok was serving us by default, and then after a few hundred videos we programmed the bots to be interested in the war because we wanted to see if the Russian bot would see more of the war after a while.

GIJN: Was it quite important when you produced the story to make it reflective of a TikTok page?

HB: Yes, because we wanted readers to feel like they were browsing TikTok — we wanted to give them the experience of these two different people and to scroll through the story the same way you do on TikTok. That is why the cards in this story are TikTok videos — so you go from the first to the second in the same way that you do with scrolling down.

CNB: We wanted the TikTok generation to read it. It might be a prejudice, but I think the concentration of the average TikTok user is not sufficient to tolerate a very dense long read. It was really important to create an easy read with the feeling that you were in the TikTok universe, because most users scroll through the page with ease, with a lightness. We wanted to create the same feeling.

GIJN: How important do you think different data presentations such as scrollytelling are to making an investigation approachable to everyone?

HB: I think it depends very much on the story that you want to tell. Our main goal was to show the main differences on TikTok, and this format is similar to TikTok and it works well in this story. We have also seen many instances where we don’t feel it works as well because sometimes it feels like you’re just scrolling and scrolling and getting a picture and a little slice of text… I think if you have a very clear idea and it’s not too long then it may work well.

CNB: We thought hard about it and we have used this theme before. We see that it has quite a high exit rate and people come into it and see they have to scroll a lot and they may think: okay, I’ll just head back later. So, we thought hard about if we should do it or not, but in this case it was the right choice because of the TikTok theme. But I have become more and more wary of using scrollytelling.

Some of the videos shown in the content stream of the fictional Ukrainian TikTok user, Nykolai. Image: Courtesy NRK

GIJN: When organizations do deep investigations it can be quite dense. Do you think walking an audience through an investigation as you do with this story is an important way to conduct investigations?

CNB: Of course it’s context-dependent. TikTok in its nature is kind of a light thing — this story would be something else if it had been about trafficking. I would say that very early on from this investigation we were focusing on storytelling – that was a very important part of this article and I think some of the things we did, the thing about the neighboring cities was important because you can see that Kharkiv is here, Belgorod is there. It’s easy to visualize the city you live in, you know how far you get if you go 80km — not far — and people in these two cities still live worlds apart. We know it’s a border and they are two neighboring cities — that’s a storytelling technique.

Also, by giving our bots names and pictures — the names are taken from the top 10 common names in Russia and Ukraine and the pictures are created through artificial intelligence — the readers get a sense of “Oh, this is Nykolai, he looks like this. This is Alexei.” Instead of saying the Russian bot or the Ukrainian bot, you have names so it gives a feeling of a person even though it’s data.

GIJN: On a cognitive level, how do you approach a story in terms of thinking and feeling?

CNB: I’m quite new to investigative journalism and to data journalism, but I’ve caught the bug — it’s really cool and I love it. But my background for almost 20 years was in feature writing. I’ve done a lot of portraits and feature pieces from around Norway and abroad. I’ve worked a lot with storytelling, but I’ve worked very little with data journalism, so that’s kind of a new feature for me. But, it’s nice to use the background that you have in a new area. This also may be a prejudice, but I think a lot of data journalists are really into the data stuff and tend to forget that storytelling is equally important. Henrik is a really good visualization guy, he can create really cool visualizations and he is also very good with the data. When you combine things, when you have a [different] background you can maybe see things that perhaps people who only work with data can’t see.

HB: Christian is a very good storyteller and he located these cities and saw that we could tell stories with these two concrete cities. He came up with using these names and personalizing the bots, while I saw stuff like ‘it would be really cool if this border stays from one card to the next.’

Bjørke (left) and Bøe speaking at the Nordic Media Days festival. Image: Courtesy of Ketil Moland Olsen

GIJN: Do you have any tips for other organizations on how to utilize these kinds of platforms?

CNB: I think it’s important to think about your target group. We wanted the TikTok generation to read this, so it felt quite natural for us to use some of the same themes and to make them feel at home. At NRK, we have this thing about writing in a way that you can look people in the eye and tell them things. You don’t tell them from above like ‘Hear ye! Hear ye! I will tell you something about this, so please listen to me.’ It’s one of the things we did with this story: like I’m telling this to a friend. If you are investigating social media that most people are using, you need to, at least I think it’s important to, use some of the same vibe.

GIJN: Do you have any general tips in terms of what to investigate during a conflict, how best to utilize what skills you have, and maybe what you want to bring into an investigation?

HB: We have been very lucky with the group we work with because it consists of people with different skills — we have some that are good at photography, video, data journalism, and storytelling. When you team up with the right people with different skills I think it makes it much easier to create something good. It’s also important to trust each other. I know that Christian is very good at storytelling, so it was good that he wrote the text and we worked a little bit differently than we usually do in this article because we built it together, but we’re doing different things simultaneously. While he was writing I was creating graphics and illustrations for the cards and we called each other and we said either “that’s great” or “improve it a little.”

GIJN: Is there anything you would have done differently with the story?

HB: It is important to keep in mind we did not do a deep investigation with many bots or over a long period of time with plenty of data. It was just a picture of how it was then and there. [One thing we learned]… we could have made it easier because we didn’t gather the video url’s, so we had to find them again, and do a lot of searching of TikTok videos.

CNB: In technical terms, there are a lot of things we would have done differently. Of course there are a lot of things we would like to dig into deeper, but I think given the time frame we had we covered what was necessary. In a way, I think we dug deep enough and managed to get up again to tell the story. Of course, there are a lot of questions we still have and we were really glad that other people followed up and also researched and investigated data algorithms.

Additional Resources

Beyond Viral Clips and Lip Syncing: A Guide to Investigating on TikTok

Using Snapchat as an Investigative Tool: Q & A with Paul Bradshaw

How Journalists Can Investigate on Telegram

Hanna Duggal is a freelance data journalist based in London. She has reported on issues such as policing, surveillance, and protests using data. Her work has been published by Al Jazeera and The Calvert Journal.

Hanna Duggal is a freelance data journalist based in London. She has reported on issues such as policing, surveillance, and protests using data. Her work has been published by Al Jazeera and The Calvert Journal.