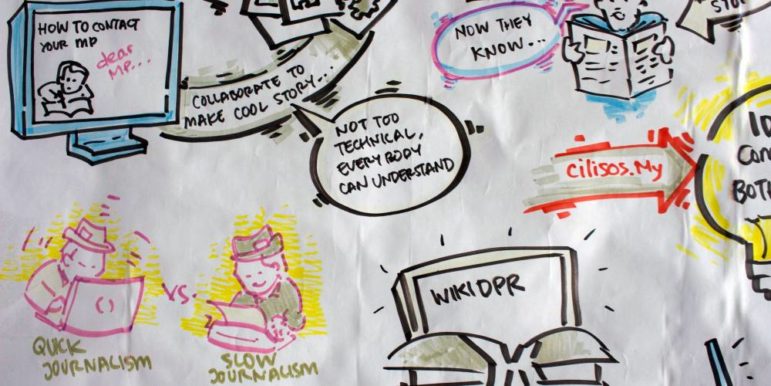

A visual representation of Sinar Project’s data work.

Data. It’s the buzzword of the moment. Gathering it. Analyzing it. Improving policy with it, and making money from it. For journalists, data can help keep governments accountable and expose wrongdoing.

But that doesn’t mean data is necessarily easy to find or use.

In Malaysia, the Sinar Project has taken up the challenge of collating patchy government statistics to provide the public, and journalists, with useable data.

Taking its name from the Malay word for sunlight, Sinar hopes to encourage government agencies to become more transparent and accountable — to embrace the idea of “Open Data” as much as “Big Data.”

Taking its name from the Malay word for sunlight, Sinar hopes to encourage government agencies to become more transparent and accountable — to embrace the idea of “Open Data” as much as “Big Data.”

“Government information is really important, but the information is actually hard to get to,” says Sinar founder Khairil Yusof. “As tech people, we do have the skill set that can make it easier for everybody.”

Sinar has its roots in the activist movement that rose from the Bersih 2.0 rally in 2011, when tens of thousands of Malaysians took to the streets calling for free and fair elections and an end to corruption.

In the crowd were, as Khairil describes them, “tech types” who were suspicious about government plans to regulate the IT industry. “All of them felt we need to do something for the country,” Khairil told Splice in an interview in the Kuala Lumpur studio apartment where Sinar is based.

“I suppose this was the first time we had this civic-tech movement in which people thought maybe we should use tech for good. It was the idea that we could build these tools for the public good.”

Malaysia’s government is an enthusiastic supporter of “Big Data” and the digital economy, which the World Bank estimates makes up about 18% of the country’s GDP.

But a lot of data doesn’t necessarily translate to useful data, says Khairil. “One of the problems Malaysia faces — and it’s not just a Malaysian issue, it’s a global one — is there’s very limited data in terms of governance and transparency,” he says. “There’s very limited open data related to budgets, there’s limited data on detailed expenditures on how government is spending, procurement — as in contracts and whatnot — and limited details on beneficial ownership of companies.”

One of Sinar’s first projects was relatively simple. MyMP is a database of members of parliament, their constituency boundaries and their work, freely available online using open source technology. The project was recently expanded to Myanmar, where it had a greater impact than in Malaysia.

One of Sinar’s first projects was relatively simple. MyMP is a database of members of parliament, their constituency boundaries and their work, freely available online using open source technology. The project was recently expanded to Myanmar, where it had a greater impact than in Malaysia.

Sinar has also mined parliamentary replies — often the only time when the government provides information on more “sensitive” topics — to create databases, including one on the incidence of sexual assault. (In Malaysia, crime statistics are not publicly released.)

In 2015, on the sidelines of the International Anti-Corruption Conference, Khairil and other open data activists worked round-the-clock to create a database of construction contracts being awarded by the government. Using data uploaded onto the website of the Construction Industry Development Board, they set out to match construction contracts with the names of politicians and reveal the private interests of public officials.

Some of those whose business activities were exposed in the resulting online database have been charged with corruption by the Malaysian Anti-Corruption Commission. Among them was Johor state politician Abdul Latif Bandi, who was charged with 13 counts of money laundering in June.

Lackluster Local Media

But despite the wealth of information in the database — stretching over 15 years — the project and Sinar’s other work has struggled to gain traction in the local media.

“We still see data as infographics,” says Kuek Ser Kuang Keng, a former reporter with online newspaper Malaysiakini who now trains journalists across the region in data. “There has to be an awareness that data is important. We have NGOs that have the technological capability and the resources, but the media has to play its part to use and publish it.”

But it’s not just about the availability of data. Malaysia has a raft of laws, including the Official Secrets Act and the Sedition Act, that leave people vulnerable to investigation for disclosing information the government would prefer not to share with the wider public. And while Freedom of Information legislation has been passed in Selangor and Penang states, there is no law at the federal level. Nor is there protection for whistleblowers.

Khairil Yusof, the coordinator of the Sinar Project, in his Kuala Lumpur office.

A few local journalists have picked up on Sinar’s work, particularly on socio-economic issues. A series of stories in the Malay Mail Online, for instance, used official data to explore the lives of the people in government flats in Kota Damansara on the outskirts of Kuala Lumpur.

Creating an impact is important for an organization like Sinar, which relies largely on grants and donations to stay afloat — which at times has been a struggle. Journalists can help transform dry numbers into a story that people can relate to and understand.

“Charts are fancy and stuff but they don’t connect with people,” Khairil says. “I get excited about the numbers and can imagine the situation for why those numbers are bad — a cut of 50 million and clinics closing — but people need the imagery, they need the human story behind it. That’s the part of the story that’s often missing with the focus on data journalism.”

This post first appeared on The Splice Newsroom site and is cross-posted here with permission.

Kate Mayberry has been a print and broadcast journalist in Southeast Asia for over 20 years, and was part of the team that launched Al Jazeera English in 2006. She freelances for such media as Mongabay, Al Jazeera, and Nikkei Asian Review.

Kate Mayberry has been a print and broadcast journalist in Southeast Asia for over 20 years, and was part of the team that launched Al Jazeera English in 2006. She freelances for such media as Mongabay, Al Jazeera, and Nikkei Asian Review.