How can media make sense of a country that has over 1.2 billion people (about 17 percent of the global population), close to 800 languages, an electorate of 814 million, and the largest urban agglomeration in the world?

How does one plan for a country where, at the end of 2012, about 22 per cent of the population lived below the poverty line (with a daily spending of less than about US45 cents in rural India and US55 cents in urban India), but which also has 89 billionaires and features fifth in the Global Rich List? The country’s latest Census in 2011 was taken with the help of 2.3 million enumerators travelling to more than 630,000 villages and more than 5000 cities. Census officials counted the thousands of homeless scouring footpaths and railway stations, while managing to include even the lone surviving Pakistani terrorist behind the 2008 Mumbai terror attacks.

In a country so socially, economically, culturally and politically diverse, one would assume that statistics would be a crucial component of news as a way to ensure inclusive, truthful, and insightful coverage. Sadly, realities on the ground paint a different picture, and the media seem to be largely indifferent to the lure of digital data journalism that is charming global media houses.

A Goldmine of Data

India.gov.in, the Indian government’s open data portal.

Ironically, India, according to experts, has some of the finest data collection organizations among developing countries, with a few good enough to take pride of place alongside the best in the world.

“As far as the availability of data goes, India will be ahead of any of the developing countries in the world,” says Prof. Nagaraj Karkada, a respected statistician and head of the research wing at the Asian College of Journalism in Chennai, South India. “The pre-independence initiatives of the British and the post-independence initiatives during the Nehru era ensured this.”

The British, who were motivated by the need to govern a country that they did not belong to, set up decentralized systems with colonels gathering data at the village level and passing it on.

Post-independence, Nehru’s vision of mass industrialization and planning occasioned the need for reliable data and this set off another surge in data gathering.

Statistics are gathered both at central and state levels. At the center, the Statistics Wing of the Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation (MoS&PI) is made up of the Central Statistical Organisation (CSO), National Sample Survey Organisation (NSSO), and Computer Centre. India’s open government portal, data.gov.in, features nearly 10,000 resources and 240 visualizations. There are also several private organizations that work in this area, largely serving the needs of business.

Why then, when there is a felt need and the basic resources to fulfill it, is the media not subscribing to the idea?

Dumbing Down the News

“When data journalism as a form of journalism was gaining respectability, the Indian media was undergoing a transition away from serious informational and critical journalism to one with a greater focus on soft stories needing less reader or viewer attention,” argues Professor C.P. Chandrasekar of the Centre for Economic Studies and Planning at the Jawaharlal Nehru University, Delhi.

The cut-throat competition for eyeballs ushered in by the explosion of television channels and the spate of print and online publications in the country in recent years may account partly for this unhealthy trend.

The tabloidization of the media has dumbed down the quality of news and shifted the focus from information and transformation to 24×7 breaking news and frenzied bids to increase TRPs (television rating points).

In this scenario, it makes little short-term economic sense to focus on slow-to-produce but meaningful stories, when the money and the viewership appear to come from superficial and sensational over-the-counter fare.

An unfavorable cost-benefit ratio, the dearth of time and the challenge to both train journalists and retain expert non-journalists contribute to the problem.

Rajesh Mahapatra, executive editor at the Hindustan Times, shares his experience trying to set up a strong research and statistics wing at the newspaper. Financial constraints, high attrition, challenges of prioritization are all impediments, in his opinion.

“It took me six long years to set up a research wing at the Hindustan Times,” he explains. “In the first instance, my top resource quit to take up a job that paid twice as much and gave him the prominence of being a top-level economist at a prestigious organization. His replacement, a bright economics graduate with very impressive academic credentials, got lapped up by a corporate house about six months back.” Mahapatra has since given up efforts to consolidate his research team and feels outsourcing could be the way forward. Journalists also need to accord data experts their due respect, he adds.

His views are in tandem with those of Prof. Karkada. “For years, at every opportunity, I have tried to persuade media heads to set up a back-end wing with expertise in various areas including statistics,” he says. The “jack-of-all-trades” approach does injustice to the sense and sensibilities of the reader, he adds. A strong research and expertise wing will help journalists source stories that need to be told and tell them well. “If every media house finds it financially unviable to have its own research and statistics wing, at the very least a group of them can come together and form one,” he suggests. “The costs are not huge but the benefits will be significant.”

Signs of Hope

Among the notable outlets for Indian data journalism is the Economic and Political Weekly, an intellectual journal covering the social sciences “They make it a point to draw reader attention to the latest surveys and studies that are available,” says Prof. Karkada, who feels the magazine is among the best in India in terms of telling stories with numbers.

However, C. Rammanohar Reddy, the magazine’s editor, is modest about the publication’s attempts at data journalism. While he admits that the EPW does process a lot of information, he says the information is put out in traditional ways that he terms “old” data journalism.

However, C. Rammanohar Reddy, the magazine’s editor, is modest about the publication’s attempts at data journalism. While he admits that the EPW does process a lot of information, he says the information is put out in traditional ways that he terms “old” data journalism.

“Data Journalism is a highly skilled job; the ability to visualize a story must be combined with the careful use of information,” he observes. “I do not see any Indian media outlet, print or online, doing so satisfactorily, though many are trying.”

One significant step forward is the 2011 founding of Mumbai-based IndiaSpend, an independent non-profit which describes itself as “the country’s first data journalism initiative.” The group aims to become an “agency of record” for data and facts on the Indian economy. Staffed by journalists and financial experts, IndiaSpend has attracted attention with data-driven stories on Hindu-Muslim clashes, the vast numbers still mired in poverty, and analysis of India’s shifting electorate.

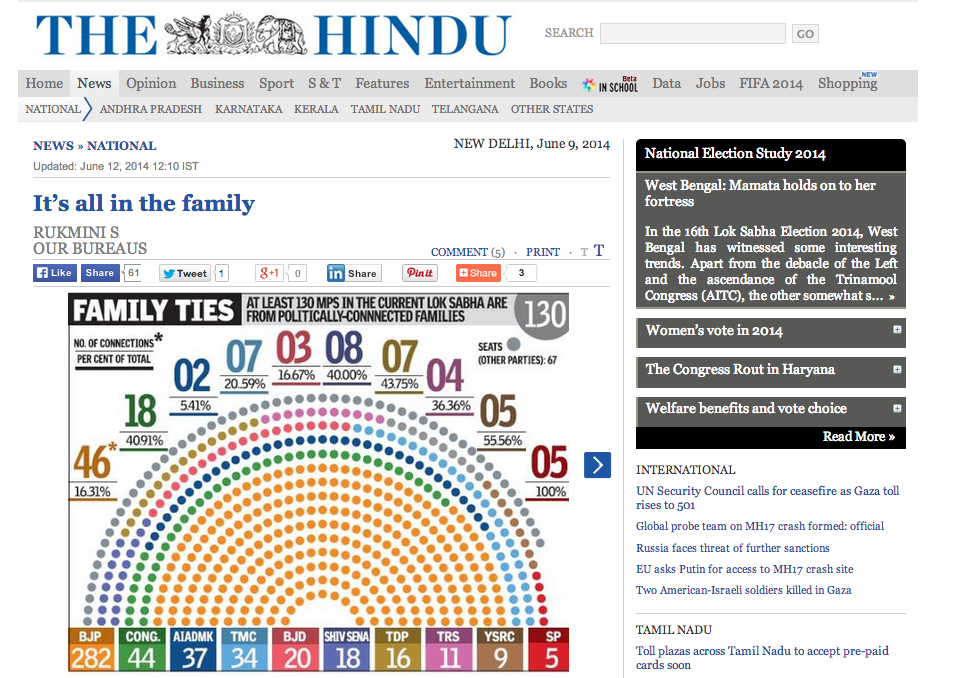

There are other noteworthy examples. A June 2014 analysis by The Hindu found that at least one quarter of MPs recently elected to the Lok Sabha (India’s lower house of parliament) are from politically connected families. The online business site Quartz has done pieces looking at data on India’s huge money-losing bus system and the vast amount of smuggling between India and Bangladesh.

India’s online Quartz news outlet, founded in 2012. Smart use of data, but where are the in-depth investigations?

But there are few if any examples of in-depth investigative reporting that utilizes extensive data analysis, as can increasingly be found in Western media outlets. (See, for example, winners of the Philip Meyer Award, sponsored by the U.S.-based Investigative Reporters and Editors, or the Data Journalism Awards given by the Global Editors Network.)

Another area of debate is opinion polling by the media, a popular trend in India which the country’s media also groups under data journalism. Prof. Karkada vehemently questions the need for polling by the media, given, he says, that the polls fulfill no journalistic purpose, failing even the paramount one of truth-telling.

Mahapatra of the Hindustan Times justifies the trend and feels opinion polls do have a role to fulfill. “Curiosity and the need to gossip are innate human traits and opinion polls do serve a purpose,” he argues. He does add a word of caution, however, about the need to frame the question correctly and be clear about the answers that are being sought.

While it is heartening to see the flood of visualization tools available today, there is an almost unanimous consent on the fundamental difference between beautiful data visualization and meaningful data visualization. Design should enrich rather than take center-stage, according to the general consensus.

A good story needs truth, context, insight, and impact. Design is only one aspect. “Presentation is not the critical issue,” points out Mahapatra. Understanding data and telling the right story in context, with insight, impact and broad takeaways for the average reader are more important, he says.

The Next Generation

Understandably, young journalists and those at the threshold of their careers, as digital natives, will be more adept at picking up digital visualization skills. At the Asian College of Journalism in Chennai, India, journalism students are taught a module on news and numbers. Students of the new media stream are also introduced to the latest, often free tools that help with visualization such as Google Fusion Tables, Tableau Public, and mapping tools such as Carto DB and Datawrapper. They are also introduced to coding.

Nasr Ul Hadi, a data journalism expert and Vice-President at iamWire, a media and technology start-up based in Delhi, has been working in this area for many years. He endorses this method of introducing students to data visualization while providing them with a basic grounding in code.

“It’s important for journalists to be able to do both,” he reasons. For instance, a cub journalist or a journalist familiar with digital tools might be able to create three standalone elements for a story. However, to tell the story in an engaging manner, he or she should be able to incorporate all the different elements into the multimedia story so they all fit together nicely, Hadi explains.

If journalists have to rely on technical staff every time thet need to tweak code for a project, it would put considerable strain on resources. But, with a basic understanding of coding, they will not only be able to independently handle the whole effort, they will also be aware of the limitations and possibilities, Hadi says.

Hadi, who is also actively involved with the New Delhi wing of Hacks Hackers, a global collective of people interested in the intersection between news and technology, says that groups like this help both journalists and technical experts. While journalists are able to familiarise themselves with systems, code and design, technology professionals often get fascinated with the potential and possibilities of applying their expertise in journalism.

But what about pay? Can a media house match salary levels offered by the IT industry?

Nasr Ul Hadi proves the point by pulling out salary details of CTOs of some of the mainstream media, some making as much as US$50,000 annually. “Not only are the salary levels impressive, most media house CTOs are also much younger than the average IT firm CTO and once they get into the thick of things, they find their work interesting and challenging enough to stay on,” he says.

Not So Open Data

Other factors remaining favorable, access to open data is crucial to meaningful data journalism, and mere availability of data without ease of access serves no purpose.

Ravi Bajpai, multimedia editor of the Hindustan Times, speaks from experience. In an earlier role with Down to Earth, a science and technology publication, Bajpai routinely found himself using free data visualization tools. While he is optimistic about the prospects for digital data journalism, he is quite critical of the quality of open data.

“Open data is hardly available in India,” he says. “The Indian government’s idea of open data is limited to the Right to Information Act. That legislation is perhaps the best tools data journalists can exercise to access robust data sets.”

He is critical of the fact that it could take an inordinately long time to access comprehensive government data on basic issues. “The time loss proves costly and the story often does not see the light of day,” he observes.

While he is appreciative of data.gov.in as a first step to open data, Bajpai feels the project potential has not been fully exploited. “To illustrate, www.data.gov.in doesn’t have either the shapefiles or kml files (data formats used for Google mapping) of Indian parliamentary constituencies that are needed to build interactive color-graded maps on Google Fusion tables, a mapping tools used by publications like the Guardian,” he says. “Imagine how useful it could be to journalists covering the Indian general elections 2014.”

Despite the criticisms, change appears just around the corner. The experts and the media practitioners are optimistic. With mobile and internet platforms growing at impressive rates, market forces will propel media firms to take data more seriously. Hopefully, the quality of journalism will also improve in response to demand-supply persuasions.

“So long as serious journalism exists, the amount of data journalism is I think bound to increase. What is under threat is serious journalism that privileges fact and analysis above baseless opinion delivered in a high pitched tone,” observes Prof. Chandrasekhar.

Mahapatra, while speaking in complimentary tones about the HT group magazine Mint’s efforts in this area, talks about the future as being about intelligent collaboration between agencies that specialize in this area (such as Indiaspend.org) and media houses.

Meanwhile, as Nasr Ul Hadi points out, senior, mid-level, and fresh journalism graduates will need to equip themselves to harness this wonderful opportunity that data journalism presents.

Whether to investigate corruption and crime, or enquire into what needs to be done to guarantee ordinary citizens of India their constitutional rights, there is little doubt that data journalism will help journalists fulfill their obligation to the truth and remain loyal to the people they are serving. Indian media needs to acknowledge this big opportunity in data and soon.

Priya Rajasekar is a freelance journalist and columnist. She is also assistant professor and coordinator of the new media stream at the Asian College of Journalism in Chennai, India. @priyaarajsekar.

Great read! Although, you should check out the data driven journalism and data visualisation work done by Rediff Labs at labs.rediff.com.

It is always good to read in print what we already know (read those within the industry.) I am a lifestyle features writer (the divide between journalist and writer sure befuddles me but when you write features, then you are never given the designation ‘features journalist’ but just ‘features writer’, is this something we see only in India or abroad as well?) and am right now working with a health magazine. Sure, the readership is very niche and small (if you compare it with TOI or Navbharat Times i.e, though I will never know the official number, my workspace believes that is none of my business!) but they need well informed stories as well, not just the people who are poor in our country. What then about such niche journalism that can benefit from data? First of all, can it benefit at all? If so, how? Has anyone even thought about that? If I want to write about prostate massage or arranged marriages in India or how the diets that nutritionists recommend today has been theorised by well meaning but upper caste Brahmin men (Vishnu Shatrugna says in a ‘Down to Earth’ interview), do I need data? If I need to write about health threats (sudden cardiac arrest or diabetes 2) or myths about depression or suicide for a young, upwardly mobile readership, should I not get training in number analysis? Why was this never even mentioned at the premium journalism school I was at, is one thing to ponder over. I want to write about the ideas I expressed but frankly my editors don’t know or read or write or follow health stories. Even if I do write some of those, they will be poorly edited and may lack a vision or perspective. Certainly the so called editors/ senior journos need training themselves or at least the will to invest in training.

Thanks for the comment, Priya. I can well understand your frustration. I suppose, for most people at decision-making levels (editors are invariably accountable to the management and it is almost impossible to keep that kind of interference completely away), return on investments is the driving force and you mention you are working for a niche magazine. This can only mean an even closer watch on ROI. Of course, health-research is almost always backed by data and it would be myopic to ignore that.

However, this phenomenal growth in the availability and accessibility of data is a recent development, and we need a few big success stories in India before those set in their ways shed the skepticism and take notice. For this to happen, some strategic, well-timed pitching of story ideas may be the way forward. Perhaps, with that, the coin will drop and editors will make a beeline for the training and the software. After all, as they saying goes, “nothing succeeds like success” and we have a great deal of data to prove that!

Very informative. Tomorrow on 19th October I am going to attend a workshop on data Journalism organized by Gujarat Media Cub at Ahmedabad. One of the speakers is Dr. Umashanker Pande from the University of Calcutta. While doing some homework I came across your Data Journalism article. Really informative.