Democracy cannot survive too much ignorance… I don’t worry about our losing Republican government in the United States because I’m afraid of a foreign invasion. I don’t worry about it because I think there is going to be a coup by the military as has happened in some other places. What I worry about is that when problems are not addressed, people will not know who is responsible … That is the way democracy dies. And if something is not done to improve the level of civic knowledge, that is what you should worry about at night.

— David Souter, Former U.S. Supreme Court Justice

The media, civil society, and democracy are under unprecedented duress around the world. It is important to see these phenomena as interconnected—to understand that the decline of the civic media poses a threat to civil society and, ultimately, to the democratic process itself. And it’s vital that philanthropy responds to this threat. In the face of these disturbing contemporary trends, philanthropy offers one of the few social resources with the potential to protect the civic role of the media and sustain civil society’s vital function in democratic life.

The media, civil society, and democracy are under unprecedented duress around the world. It is important to see these phenomena as interconnected—to understand that the decline of the civic media poses a threat to civil society and, ultimately, to the democratic process itself. And it’s vital that philanthropy responds to this threat. In the face of these disturbing contemporary trends, philanthropy offers one of the few social resources with the potential to protect the civic role of the media and sustain civil society’s vital function in democratic life.

In the past, the media’s complexity, political sensitivity, and historical tradition of support by commercial or governmental sources have all been deterrents to philanthropic investment. Additionally, the current philanthropic mindset tends to gravitate toward solving concrete, technically fixable problems and away from engagement with such knotty challenges as protecting and improving the quality of civic discourse.

Yet the urgency of current circumstances demands new thinking.

The Public Sphere’s Importance to Civil Society

To understand why, consider first the historical context of the public sphere and civil society. Modern civil society developed with an intimate relationship to the vehicles of public discourse—“mass media” in the form of newspapers, pamphlets, magazines, radio, television, and other forms of civic communication. In fact, a free and open system of civic communication can be understood as one of the constitutive elements of civil society as it has evolved from the 17th century to the present day, along with the rule of law, free and independent associations, and philanthropy.

Jürgen Habermas was the first modern theorist to describe this relationship, noting in 1962 that the public sphere—the realm in which a reasoning public shaped civic life—had emerged as an essential feature of early modern civil society (during the period known as the Enlightenment, in the 17th and early 18th centuries).

For Habermas, this sphere “presupposed strict separation of the public from the private realm in such a way that the public sphere, made up of private people gathered together as a public and articulating the needs of society with the state, was itself considered part of the private realm.” Although in his early work Habermas described this phenomenon as a conceptual ideal existing as a transitory phase, he has recently reemphasized the essential function of a public sphere that informs public agendas and enables democratic decision-making, free of governmental or commercial control, in today’s world.

Interestingly, the French diplomat and historian, Alexis de Tocqueville famously described this role of civic communication in both volumes of Democracy in America (1835, 1840), in his observation of the central function of newspapers in creating the conditions for democracy in early America, which stood as a radical departure from the elite control of the press that had been taken as a given in European societies. As he put it: “The newspaper brought [citizens] together, and the newspaper is still necessary to keep them united.”

Interestingly, the French diplomat and historian, Alexis de Tocqueville famously described this role of civic communication in both volumes of Democracy in America (1835, 1840), in his observation of the central function of newspapers in creating the conditions for democracy in early America, which stood as a radical departure from the elite control of the press that had been taken as a given in European societies. As he put it: “The newspaper brought [citizens] together, and the newspaper is still necessary to keep them united.”

Habermas and Tocqueville, writing from different traditions, nonetheless articulated a common view of the essential role that the public sphere plays in civil society, as enabling an independent citizen voice empowered to steer public policy and providing a vehicle for radically differing voices to interact freely on public matters.

We agree, and it follows that the weakening of the system of free communication severely undermines a democratic system. The hallmark of authoritarian societies, in fact, has been the repression of independent institutions that might challenge the central control exercised by the dominating state or oligarchic group. Examples abound; consider post-WWII Eastern European states, Maoist China, Burma in the last half of the 20th century, Iraq under Saddam Hussein, Franco’s Spain, Pinochet’s Chile, Cuba under Fidel Castro, and the most notorious cases of Nazi Germany and Stalinist Russia.

Historically, this control has been exerted through the imposition of top-down state power, eliminating independent organizations and dissenting voices, often in the name of adherence to an overriding ideology—political, nationalist, or religious. One of the first priorities of all such regimes is seizing control of the media. If the public lacks an ability to communicate about important matters of civic concern, it also fails to have an ability to organize effectively through independent associations, draw upon philanthropic resources to support them, defend the legal institutions that protect the public sphere, or develop consensus positions that could be translated into actions through the electoral process.

But in recent years we are beginning to witness a new and quite different way in which the public sphere is being undermined. Civic communication is increasingly threatened by repression not from top-down authoritarian systems (although this too still exists) but rather from corrosive interior social and economic forces, described in the next section. These emerging economic and technological influences have become the primary drivers of civic media. And the result is a significant deterioration of the quality and quantity of accurate civic information that ultimately threatens the public’s ability to form coherent views and reach democratic decisions.

Weakening Civic Communication

Five trends of the late 20th and early 21st centuries reveal this general pattern: 1) a radically diminished funding base for print media, 2) increasingly fragmented audiences, 3) an accelerating pattern of random and instantaneous digital dissemination of information, 4) video’s increasing displacement of the written and spoken word, and 5) diminishing amounts and lower quality of civic education, and related declines in knowledge of public affairs. Individually, these trends are problematic; together they pose a severe threat to democracy.

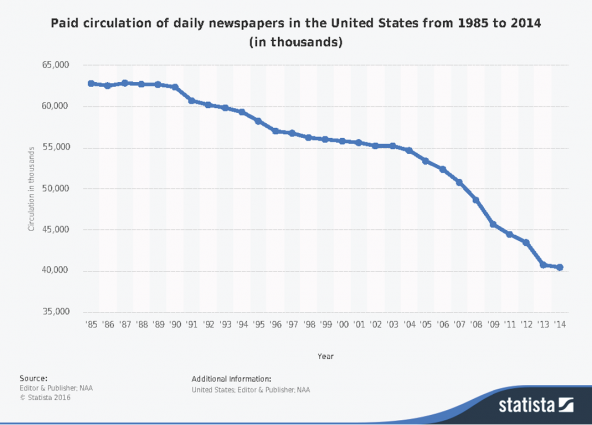

Evidence of decline in the quality and quantity of civic communication is apparent across the spectrum of modern media. Consider the precipitous descent of US newspaper circulation (see chart below). Circulation has dropped from 63 million in 1985 to 42 million in 2014 (a 32 percent decrease), despite a growth in the US population during that period from 238 million to 319 million (a 34 percent increase). Thus, the per capita figure for newspaper consumption in the United States fell from 26 percent to 13 percent from 1985 to 2014. A wide range of studies have described this decline and have projected a continuation of these trends, leading toward what many see as the possible extinction of the printed newspaper in the coming decades. And similar patterns prevail in all liberal democracies.

Paid circulation of daily newspapers in the United States from 1985 to 2014. (Image source: The Statistics Portal)

Some argue that such figures simply demonstrate that printed newspapers are succumbing to natural market forces, and that they’re being replaced by alternative waves of digitally or otherwise disseminated information about public affairs. But Tim Wu and many other observers provide strong evidence that most forms of traditional civic communication, not just newspapers, are experiencing similar declines both quantity and quality in the contemporary era.

Four other sources present the possibility of financial support for print journalism, to offset dropping revenues: public financing, Internet pay portals, subscriptions, or support by foundations and other philanthropic donors. Of the four, though, we believe that only the last holds real promise for substantial expansion.

Our view is at odds with the argument made by Professor Robert McChesney and The Nation correspondent John Nichols that much greater public support might be sought in the United States from a variety of government programs, taxes, and user fees. But we believe that American resistance both to higher taxation and to increased government involvement in the media would defeat such an effort. What’s more, in European countries that already enjoy high levels of public support for media, this funding has not prevented continued decline—as much as negative 4.7 percent between 2014 and 2015. And as for online paywalls and increased subscriptions, the numbers thus far just don’t add up. Philanthropy, as we said at the beginning of this article, is the most viable and promising option.

Here’s what would need to happen to make any philanthropic efforts to preserve and sustain the civic media—and by extension, the democratic way of life—effective.

The Philanthropic Imperative

First, charitable donors would have to increase significantly their investment in the news media. Journalist Rodney Benson estimates that the current level of philanthropic support in the United States for this purpose is $150 million. Simply increasing the amount contributed to the support of news media to 1 percent of total US giving would generate more than $3.7 billion.

Generating philanthropic support to respond to this crisis in civic communication would entail two fundamental commitments by funders: 1) a commitment to direct support toward strengthening the media per se rather than to use the media for advancing another philanthropic cause (for example, environmental protection or improving public health), and 2) a commitment to maintaining a separation of control between the sources of financial support and the content produced by the supported organizations.

Anya Scriffrin, director of technology, media, and advocacy specialization at Columbia University’s School of International and Public Affairs, explores the importance of both of these commitments extensively in a recent report issued by the Center for International Media Assistance and the National Endowment for Democracy.

Anya Scriffrin, director of technology, media, and advocacy specialization at Columbia University’s School of International and Public Affairs, explores the importance of both of these commitments extensively in a recent report issued by the Center for International Media Assistance and the National Endowment for Democracy.

With agreement around those two fundamental tenets, a foundation could take purposeful action. At an October 2016 gathering entitled “Beyond Disruption” (BD), practitioners and scholars from philanthropy, nonprofits, government, and the media explored and inventoried a number of concrete paths philanthropy could take. Among the ideas proposed, however, we believe that five show particular promise:

1. Apply the Limited-Profit Limited Liability Company (L3C) corporate model to news organizations

The L3C combines for-profit and nonprofit characteristics in ways that can attract new capital resources to news organizations without placing priority on maximizing profits. University of Auckland Professor Gavin Ellis has argued that L3Cs “may be a means by which the news media organizations of the future could attract capital in an environment where newspapers and television stations are no longer seen as attractive investments, and news websites have a lower earning capacity than their traditional counterparts once enjoyed.” He has noted that this is a vehicle through which “trustee governance might be maintained, while allowing an entreprise to generate enough commercial revenue to sustain itself.”

2. Take philanthropically-minded ownership of news entities

Promising examples already exist of socially concerned, major investors taking ownership of newspapers with the goal of returning a profit while sustaining the quality of journalism: Washington Post (Jeff Bezos); Boston Globe (John Henry); and 63 regional newspapers (Warren Buffett), including Richmond Times-Dispatch and Winston Salem Journal. In each case, the investor has exhibited significant interest in journalism along with investment performance.

Europe, meanwhile, provides a number of like-minded examples of media owned by trusts: The Scott Trust Limited owns The Guardian, and The Irish Times Trust owns the Irish Times. A third case, the Democracy & Media Foundation (DMF) in the Netherlands, provides another model. (This foundation was one of the BD forum conveners.) Originating with a courageous loan of 1,000 guilders to a printed “illegal” newspaper, Het Parool, at the time of the Nazi German occupation of The Netherlands, DMF became the publisher of Het Parool and associated periodicals after World War II. It then grew into a shareholder in several Dutch newspapers and publishing companies. Today, DMF uses the returns on its investments “to counter all forms of totalitarianism in social and political life, and to strive for a vigorous democracy and multifaceted, opinionating media.”

Learning from the experiences of these organizations, philanthropists could build on their success and expand the reach of this type of venture.

3. Fund experimentation with new types of news organizations

During the past two decades, a number of news professionals have sought to develop new kinds of organizations to replace declining newspapers and reach new audiences while protecting free and independent media. Nonprofit examples include Pro Publica, Center for Investigative Reporting, Center for Public Integrity, and First Look Media, all of which are supported by a limited number of foundations and individual donors.

During the past two decades, a number of news professionals have sought to develop new kinds of organizations to replace declining newspapers and reach new audiences while protecting free and independent media. Nonprofit examples include Pro Publica, Center for Investigative Reporting, Center for Public Integrity, and First Look Media, all of which are supported by a limited number of foundations and individual donors.

In Europe, examples include De Correspondent, a successful Dutch-language, online journalism platform (seed funded by DMF), which launched on 30 September 2013 after raising more than 1 million euro over eight days in a crowd-funding campaign, and eldiario.es, a Spanish online newspaper created in 2012, which receives a significant portion of its revenue from socios: partners/members of the site who pay five euros a month.

In the field of investigative journalism, one venture that emerged from the BD process (and has secured seed funding) is an Investigative Journalism Production House modelled on vehicles used in the film industry. This initiative is intended to create a system that would “pre-fund” a collaborative network of journalists. Such a system would:

- Apply the same mechanism used in film financing for investigative journalism: The agency would broker ideas generated by a pool of participants to production financing entities (book publishers, TV, film, exhibition, and other commercial entities).

- Create a governing entity (a B-corporation or a cooperative) that would mediate between journalists and sponsors. It would market the original idea to all possible distribution channels.

- Provide a common funding pool: If one idea succeeds as a blockbuster, it would replenish the pool for everyone.

Another urgent need is the creation of one or more independent organizations dedicated solely to the purpose of vetting and certifying the accuracy of the content and sources of news circulated on the Internet. Responding to the vast wave of inaccurate or false news that threatens to engulf public discourse, a kind of “consumer reports” for news would provide a valuable resource for all modes of media.

Another urgent need is the creation of one or more independent organizations dedicated solely to the purpose of vetting and certifying the accuracy of the content and sources of news circulated on the Internet. Responding to the vast wave of inaccurate or false news that threatens to engulf public discourse, a kind of “consumer reports” for news would provide a valuable resource for all modes of media.

4. Endow existing news organizations or other types of civic media

Again, there’s precedent in this area providing a model that’s worth studying and building on. One institution currently supported through such an endowment-like entity is the Poynter Institute and its ownership of the Tampa Bay Times (formerly the St. Petersburg Times).

Again, there’s precedent in this area providing a model that’s worth studying and building on. One institution currently supported through such an endowment-like entity is the Poynter Institute and its ownership of the Tampa Bay Times (formerly the St. Petersburg Times).

But endowment support might be also appropriate for another kind of model institution proposed at the BD forum—a new kind of organization provisionally named LYRA. This entity would develop new methodologies to tap online and offline sources of information and deploy them through a collaborative network of different actors to expose abuse of power, collect evidence for judicial proceedings, and share knowledge. The components would involve a “constellation” of different actors and organizations—including activists, NGOs, and investigative and media outlets—working toward a common goal. The long-term goal would be reducing abuse of power, advancing transparency, and increasing accountability of public authorities.

5. Support advancement of public discourse at all levels

Beyond existing efforts to improve civic education in US schools—vitally important to counter the steady decline in civic knowledge and engagement throughout the country—there have been a number of initiatives, most notably those of the Kettering Foundation, aimed at advancing the level and reach of public discourse. One project prototyped at the BD forum envisions a digital framework, called CIVx, that would enable communities to host and facilitate collective conversations in an inclusive and safe public space. The framework’s overall aim would be to improve public debate by getting people to share their individual stories. Through CIVx, individuals would engage in civil discussion through different media such as events, videos, or publications, after agreeing to respect a set of core values (listening, inclusivity, safety), and to certain rules of engagement.

CIVx would provide an open source database of “recipes” for civil dialogue and potentially civic engagement, based on projects that have worked before in different places. The framework would also offer training for facilitators and experts who could then teach others how to create similar spaces for civil discussion.

The challenge of improving the quantity and quality of civic communication falls into the category of a classic “wicked problem” in philanthropy. That is, it is one in which the definition of (and hence the potential solution to) the problem evolves in accordance with the diverse perspectives of the participants in the system. Strengthening the structure of civic communication in democratic states will require that we grapple with exactly these reflexive elements of social change.

Clearly, additional rounds of prototyping and experimentation in multi-actor, design-mode environments similar to that of the BD event, are needed. For example, there’s much to learn from the loan program of the Media Development Investment Fund (MDIF). Operating in the global south since 2006, MDIF has deployed approximately $150 million in low-interest (1-3 percent), private capital for independent news companies. Media organizations can borrow affordable capital against the cash flow offered by their successful generation of income. Additional study could yield other, similarly viable methods of supporting independent media.

Clearly, additional rounds of prototyping and experimentation in multi-actor, design-mode environments similar to that of the BD event, are needed. For example, there’s much to learn from the loan program of the Media Development Investment Fund (MDIF). Operating in the global south since 2006, MDIF has deployed approximately $150 million in low-interest (1-3 percent), private capital for independent news companies. Media organizations can borrow affordable capital against the cash flow offered by their successful generation of income. Additional study could yield other, similarly viable methods of supporting independent media.

But that’s just one avenue, of many, worth pursuing. The consensus view of those gathered at the BD forum was that making progress on civic communication requires nothing less than fundamental social innovation. Drawing on a term frequently invoked at the event, we suggest that work in this arena is an “entangled challenge,” one in which public debate and its influence on civil society are inextricably enmeshed with other dimensions of the complex social system.

Protecting the independent media and the public sphere presents an epic challenge to contemporary philanthropy, but we believe that today’s philanthropic organizations are up to the task. To support their efforts, and multiply their impact, we encourage much wider discussion and resource allocation to what today may be the most vulnerable pillar of the democratic state.

Note: This article draws heavily upon conclusions and recommendations that emerged from an October, 2016 gathering entitled “Beyond Disruption” in Turin of 50 practitioners and scholars from philanthropy, nonprofits, government, and the media to explore the possible role philanthropy can play in addressing the contemporary crisis in civic media.

This post was originally published by the Stanford Social Innovation Review (SSIReview) as “The Civic Media Crisis and What Philanthropy Can Do.” It is reproduced here with permission.

This post was originally published by the Stanford Social Innovation Review (SSIReview) as “The Civic Media Crisis and What Philanthropy Can Do.” It is reproduced here with permission.

Bruce Sievers is a visiting scholar at the Stanford Center on Philanthropy and Civil Society and lecturer in political science at Stanford University. He is former CEO of the Walter and Elise Haas Fund in San Francisco.

Bruce Sievers is a visiting scholar at the Stanford Center on Philanthropy and Civil Society and lecturer in political science at Stanford University. He is former CEO of the Walter and Elise Haas Fund in San Francisco.

Patrice Schneider (@aristipus) started his publishing career as a journalist reporting from conflicts in Central Asia at the end of the 1980s. After managing media companies and working for the World Economic Forum, he joined the Media Development Investment Fund, where he is the chief strategy officer.

Patrice Schneider (@aristipus) started his publishing career as a journalist reporting from conflicts in Central Asia at the end of the 1980s. After managing media companies and working for the World Economic Forum, he joined the Media Development Investment Fund, where he is the chief strategy officer.