Image: Shutterstock

Editor’s Note: For the next several months, GIJN is running a series drawn from our forthcoming Reporter’s Guide to Investigating Organized Crime, which will debut in full in November at the Global Investigative Journalism Conference. This section, which focuses on money laundering, was written by Paul Radu, co-founder of the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project. For those interested in more tips and tools on covering money laundering, check out GIJN’s two-part “Investigating Company Finances” webinar, hosted by Finance Uncovered’s Nick Mathiason.

Most of the criminals I investigated over the past two decades could have been some of the world’s best entrepreneurs. They had what it takes: resourcefulness, creativity, fast thinking, motivation, the ability to network and lead, and an obvious if uncanny attraction to risk. Many of them could have been on par with the Elon Musks of the legitimate business world, but they chose crime instead and their skill sets made them into some of the most dangerous and toxic people on the planet.

They think big and their business plans are simple: “more victims, more money.” And their life is made easier by the fact that most high-level criminals operate with impunity at a continental or even global scale, where they have no natural enemy because law enforcement is generally confined by national borders and national interests.

Part One: How It Works

The Financial Blueprints of Crime

Because of the complications arising from transnational criminal enterprises, the fight against organized crime is mostly left to journalists and activists, who can network across borders and work in the public interest. But news organizations willing to take on one of the most powerful threats on the planet are limited in number and typically under resourced. The good news is investigative reporters have realized with the advent of cross-border collaborations that crime is, in many respects, a commodity and it follows general patterns making it easier to identify and expose. In short, if a criminal scheme works in a country or across a region, the same criminal model will be exported elsewhere in the world. It is the criminal blueprint and its elements that need to be understood to efficiently follow the money and stop criminals from doing business as usual.

We have to understand our adversary to efficiently investigate and reveal its illegal activities. So, let’s first go through some of the main instruments used by criminals to steal, hide, and invest their money. Then, in the second part, we’ll look at some of the best tools and ideas of our own to investigate and expose.

Criminals, both the ones just starting out as well as those who are already well established, have at their disposal regional and global infrastructure that is continuously built and maintained by what we at the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP) call the “criminal services industry.” This infrastructure entails scores of lawyers, bankers, accountants, company formation agents, hackers, reputation management companies, and many others who make money by enabling the crime and by helping the criminals invest their ill-gotten money. So, what are the main elements of a crime on the money side?

Offshore-Type Companies

A lot has been written about the offshore financial industry and the secretive companies that allow criminals to covertly steal and move large amounts of money across jurisdictions. Projects such as Offshore Crime, Inc., Panama Papers, and others brought this illicit money-laundering industry into the spotlight, and subsequent large collaborations such as OCCRP’s ongoing OpenLux project have highlighted that many landlocked countries such as Luxembourg provide or provided the same level of secrecy as the more traditional offshore locations. Understanding how criminals structure their businesses and identifying the errors they make or were forced to make is crucial when investigating high-level organized crime and corruption.

Proxies

Organized crime needs to hide behind other identities — proxies —so the offshore companies can provide the required secrecy for their transactions. During our investigative work at OCCRP, we’ve identified three main types of proxies: unaware, semi-aware, and fully complicit proxies.

Unaware proxies are people whose identities have been stolen (sometimes via large-scale information theft from internet service providers) and who have no idea that their name is being used to form a company or set up a bank account. Semi-aware proxies lend their identity documents in return for small amounts of money, but without being aware of the true extent of the criminality of the businesses or transactions tied to their name. Complicit proxies, as the name implies, are fully cognizant of the criminal schemes that they are abetting and get a chunk of the profits. Knowing what type of proxy is involved in a criminal scheme can determine what steps need to be taken by the investigative reporter trying to expose it.

Image: Jefferson Santos on Unsplash

Banks

Despite the recent rise of innovative products in the financial sector, such as cryptocurrencies, banks remain a critical part of the world’s financial systems. They are natural targets for organized crime groups, who seek to insert themselves and take advantage of the banking sector in various ways. As in the case of proxies, some banks are fully complicit, some are unaware, and some seem unprepared and perhaps unwilling to halt the criminal funds flowing through their accounts.

The banking system is made of a myriad of small, medium, and large banks and their subsidiaries. It is important to point out that small banks can only join the global financial system if they open up what are called corresponding bank accounts with larger banks, which ensure access to worldwide wire transfers. We’ve investigated many small and even medium-sized banks that were fully or partially owned and operated by criminals, but they still relied upon the largest banks in the world to send and receive vast amounts of dirty money. Smart criminals realized a long time ago that, much like law enforcement agencies are often tripped up by jurisdictional constraints, cooperation is also lacking between banks and that the financial compliance systems are geared towards identifying individual or small batches of suspicious transactions. The FinCENFiles made clear how banks can fail to identify high-volume money laundering. Criminals used this to their advantage by splitting large volumes of money between numerous banks and bank accounts, so no one bank would have a clear picture of their massive, money laundering operations.

Fake Contracts and Invoices

To execute widespread money laundering schemes, criminals use forged paperwork, fake contracts, and invoices that are attached to the banking transaction as justification. These fictitious invoices certify on paper that a cargo of, say, personal computers was sold from offshore company A to offshore company B. But, in fact, no real trade has taken place, even as the money travels between bank accounts. This illicit practice is called trade-based money laundering and it might account for the biggest chunk of this type of financial crime worldwide. It’s obviously impossible for a banking compliance officer to check the contents of every shipping container associated with a financial transaction — and organized crime counts on that.

In other instances, fake paperwork attached to banking transactions certifies fictitious loans and services with the same results.

The secret to efficient money laundering involves offering these four components as a full package to criminal groups and corrupt politicians. In fact, the criminal services industry even issues fraud manuals — sets of instructions on how to deploy companies, bank accounts, proxies, and fake invoices without triggering scrutiny from banking regulators or law enforcement. This is an example of what one of these money laundering manuals promoted by a bank in Latvia and uncovered by OCCRP — was advising clients to do:

“The delivery conditions specified in the contract or invoice should be realistic: When you specify goods, you have to think how they are going to be ‘shipped’ (weight of the cargo, volumes, address of the manufacturing plant, type of transport: road, rail, or ship.) In the case of ‘shipping’ of goods with very large volume or size, please specify a factory close to railroad or port.”

At OCCRP we call these turnkey money laundering systems “laundromats.” They act like all-purpose financial vehicles and are typically set up by a bank or other financial services company with the intent of helping clients launder the proceeds of crime, hide ownership of assets, embezzle funds from companies, evade taxes and currency restrictions, or move money offshore. OCCRP coined the term in 2014 with its investigation “The Russian Laundromat.”

A laundromat is the financial-world equivalent of the TOR network browser, which provides users complete anonymity on the internet. Laundromats allow people to split laundered money among different banks so that, much like with TOR, secrecy is preserved because no single institution has a full picture of what is going on.

Laundromats are made up of companies scattered across the world that appear independent but are actually controlled by a single party — usually the bank. The laundering process begins when a client wires money to a node in the network, often using fake paperwork showing a good or service being bought or sold. From there, the money’s parceled out to the other nodes, accompanied by more bogus paperwork. Eventually, the money is sent to an offshore company or other destination chosen by the client (minus a commission for the laundromat’s operators). The ownership and origin of the money is lost in the dizzying number of transactions, rendering it nearly untraceable, even by law enforcement. (For more on how this works, check out OCCRP’s laundromat FAQ.)

A clear example of how laundromats can evade scrutiny by some of the largest banks in the world was evident in a leaked, internal Deutsche Bank document, which details the bank’s failure to detect the Russian Laundromat that manipulated its global financial infrastructure.

Internal Deutsche Bank slide, leaked to OCCRP, describing how the bank was an unwitting partner to a massive Russian money laundering scheme. Image: Screenshot

There are many examples of how organized crime manipulates the financial systems of the world. Though the following are three examples from three different geographical regions, the pattern repeats itself and involves all or a smaller subset of the elements of the Russian Laundromat conspiracy above.

The Azerbaijani Laundromat and Iran’s Anti-sanction ‘Economic Jihad’

The Azerbaijani Laundromat primarily allowed the elites in Baku, Azerbaijan, to bribe European politicians and to siphon hundreds of millions out of the country. But OCCRP discovered that this money laundering machine was also used by Iran to bypass US and European sanctions thanks to the help of an organized crime group led by Reza Zarrab, an Iranian-Turkish criminal very close to the Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan. The money laundering conducted by Zarrab had all the classic elements enumerated above and turned into a growing geopolitical scandal between Turkey, the US, and Iran — and shows how organized crime thrives in times of unrest and can exploit political divisions.

The Troika Laundromat comprised a complex financial system that allowed Russian oligarchs and politicians in the highest echelons of power to secretly invest their ill-gotten millions, evade taxes, acquire shares in state-owned companies, buy real estate in Russia and abroad, and much more. The Troika Laundromat was designed to hide the people behind these transactions and was discovered by OCCRP and its partners through careful data analysis and thorough investigative work. The investigation involved one of the largest releases of banking information, some 1.3 million leaked transactions from 238,000 companies. To see a video explainer of the scheme, click here.

The Troika Laundromat exposé was born out of data work done on a large set of very dry banking transactions. We had to look for patterns in order to identify and isolate transactions that stemmed from what we later defined as the Troika Laundromat. We had to look for the errors, the bad links, in order to identify who was the organizer and who were the users of the system. Through careful data analysis, we finally found out that the bankers putting this together made a small, but fatal, mistake: they consistently reused just three shell companies to make payments to formation agents in order to set up dozens of other offshore companies that were themselves involved in transacting billions of dollars. These payments, which were only in the hundreds of dollars each, were of course lost in a sea of millions of much larger transactions, so we had to find them and trace them back to recognize they were part of a larger pattern. The whole Troika Laundromat came in focus after identifying this common thread.

The Riviera Maya Gang (RMG) was a ruthless and violent cross-border organization, and this case offers a clear example of how organized crime scales up and into different businesses. The bandits in this case started small in Europe as skimmers — people who steal debit and credit card numbers by implanting illegal devices or software into ATMs. Crossing continents, they then partnered up with a Mexican bank and managed to install more than 100 ATMs on the Riviera Maya — the tourist area between Cancun and Tulum in southern Mexico — generating more than $200 million a year in criminal gains. The RMG used fake documents, fake identities, and proxies not just to build their business, but also to offer shelter to fugitives from justice while using the same infrastructure to smuggle people from Mexico into the United States.

Part Two: How to Untangle It—Tips & Tools

As seen in the examples above, organized crime groups can be quite sophisticated when stealing, hiding, and investing their money. But one thing they cannot control is time. And with each passing day, journalists, activists, and other investigators are garnering more transnational reporting experience while governments around the world implement more rules about transparency, company ownership, and property.

Banking and Court Records

Access to bank records is the Holy Grail when investigating organized crime financing, but banking records are difficult to obtain because they are confidential, private documents. Reporters can’t always count on leaks and whistleblowers inside of banks and financial regulators to hand over records. But there is another way to get banking records. These types of documents are often attached to criminal court cases against organized crime or even to commercial, civil litigation. It all depends on the jurisdiction, and the US is a prolific source for global banking records that become public on the Public Access to Court Electronic Records (PACER) service.

For example, OCCRP obtained hundreds of thousands of banking records by checking PACER and filing freedom of information requests with US courts after that country opened a legal case against the Azerbaijani Laundromat kingpin, Reza Zarrab. Previously, we obtained similar records from courts in other parts of the world. These banking records are often subpoenaed in bulk by law enforcement agencies and are a boon for investigative reporters who can get hold of them.

Leaked suspicious activity reports (SAR) from financial institutions, like those obtained in the FinCENFiles investigation, can also offer a glimpse into the world of banking secrecy. Leaks will only grow in quality and quantity, and if used in conjunction with court records, they can be extremely valuable to investigative reporters and the public they serve.

Court records and especially commercial litigation between two criminal parties are also very useful to investigators as criminals get to launder their dirty clothes in public, as are divorce cases.

Property Records

Criminals like to own things and while the luxury car, watch, or other bling-y items are a must for many, the ill-gotten gains generated by organized crime often end up invested in real estates, like luxury mansions, or vast agricultural and forest lands. Investigative reporters should increase their focus on property records to untangle the investments and the scale of money laundering on the side of organized crime. In most countries, property documents are public records and will show the current owner, previous owners, as well as some financial details like the purchase price and taxes.

Company Records

National and international registries of companies can provide information not only about shareholders and board members, but in many cases also contain a company’s financial data. On rare occasions, these records also reveal banking transactions, property records, and even granular information or beneficial ownership information about offshore-type companies that might be shareholders. Quite often we get information about a beneficial owner through registries of companies or property in places where these companies invest their illicit funds. Also, keep in mind that not all information is digitized and indexed in databases, so a trip or a phone call to the registry might give you access to a lot more data than what is available online.

An important stage in exposing high-level money laundering is exposing the beneficial ownership of banks. Treat banks like any commercial company and try to find out who owns them. This is especially important in the case of newly formed, small- and medium-sized banks.

Import-Export Databases

Frequently, we use databases such as ImportGenius or Panjiva to track down import-export operations. These are expensive databases — downloading one year of a company’s US import data from ImportGenius costs $199 — but they can be helpful to identify trade-based money laundering and the companies involved with it. We have used these databases to confirm if companies involved with the laundromats were also involved in other phony commercial operations. Of note: In many countries, the annual import-export transactions are available via national freedom-of-information laws, while the United Nations Comtrade site offers useful global trade data where import-export patterns can be identified.

Aleph

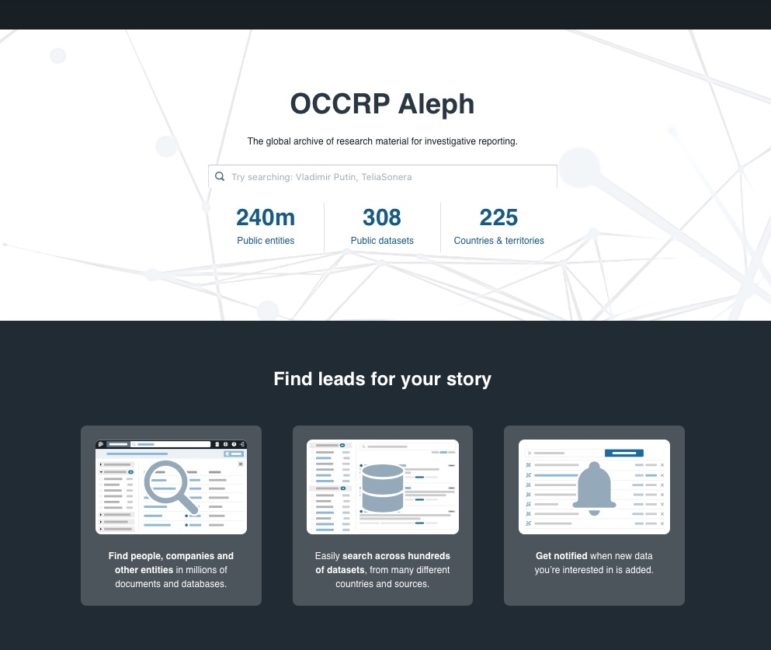

At OCCRP, we built a global archive of research material for investigative reporting called Aleph. Here, we index information on companies, property, bank accounts, court cases, leaks, and many other entities. But the indexing is just the beginning, as Aleph allows journalists to make sense of data and to identify the criminal patterns that are critical for starting a meaningful investigation in the public interest. Journalists can also keep person-of-interest watchlists inside Aleph and our system will continuously match the names in the lists against the other data contained within the system. This automates our workflow and helps ignite fresh and useful investigative reporting.

The OCCRP has developed Aleph, a useful resource that allows investigative journalists to search for public records and leaks. Image: Screenshot

What Does the Future Hold?

For the past few decades, transnational organized crime was many steps ahead of law enforcement, investigative reporters, and activists. Things started to change slowly with journalists joining forces across borders, but criminals still enjoy an advantage thanks to the huge resources at their disposal and because they are early adopters of new technology that allows them to stay one step ahead of law enforcement.

One group often overlooked are so called criminal angel investors, people who finance other criminals because the return on investment is great and crime brings more opportunity to people used to this lifestyle. Investigative reporters need to better understand the financial ecosystem built around crime, where the criminal services industry thrives and develops new money laundering and covert investment techniques.

To keep up with organized crime’s evolving techniques, investigative journalism organizations should invest time and money understanding cryptocurrencies, blockchain, non-fungible tokens (NFTs) and any other new tools of the trade criminals have adopted for their business models.

“Follow the money” will soon become “follow the code” (as in an algorithm), but in the end, it all takes a physical form in the shape of property and the visible lifestyle that crime brings with it.

Additional Resources

How to Follow the Money: Tips for Cross-border Investigations

A 10-Step Program to Fight Kleptocracy Around the World

GIJN Series: How to Uncover Corruption

Paul Radu is co-founder and chief of innovation at OCCRP. He founded the organization in 2007 with Drew Sullivan. He leads OCCRP’s major investigative projects, scopes regional expansion, and develops new strategies and technology to expose organized crime and corruption across borders.