Image: Courtesy The Caravan

Editor’s Note: At GIJN, we’ve long been impressed with the gutsy journalism of Caravan. In an India now under the sway of Hindu nationalism, the magazine is one of a dwindling number of independent, watchdog media outlets. So we were pleased to see this in-depth feature on Caravan, its dynamic editor Vinod Jose, and the impact of Hindu nationalism on a free press in the world’s largest democracy. We are indebted to author Maddy Crowell and The Virginia Quarterly Review, where this story first appeared, for permission to republish.

The offices of Caravan, a small but influential Indian monthly magazine, are housed on the third floor of a Soviet-style building in New Delhi. For a long time, Vinod Jose, the magazine’s executive editor, didn’t give much thought to the view outside his window: a budding thicket of gulmohar trees where, down below, smokers convened in small circles on their lunch break. But then, a few years ago, the view began to change. The netted steel cage of a new building began to rise out of the foliage, piquing Jose’s interest: It would be, he soon found out, the New Delhi headquarters for the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), India’s most powerful right-wing Hindu-nationalist organization, and a longtime fixation of Jose’s journalistic career.

“A colleague once told me that if he were writing a profile of me, that this would be the opening scene,” Jose said, gesturing to his view of the RSS headquarters, when we met in April 2019. Jose, who is forty and speaks in tranquil bursts, carries himself with a calm authority that can often feel out of place in Delhi’s cacophony. He crossed his office, passing precariously stacked books and locked filing cabinets with labels such as “The Gujarat Files” and “Amit Shah,” then fell into a worn swivel chair. For Jose — one of India’s more subversive journalists, and my former boss when I was an intern at Caravan six years ago — pointing out a good opening scene was no different than providing me with the weather forecast for the day. His life and his journalism are practically inseparable.

He was right: The scene was, indeed, a good metaphor. Caravan and the RSS are intimate adversaries in the Indian public sphere. Founded in 1925, the RSS has long advocated for India to abandon its pluralistic ambitions and become an entirely Hindu nation — an idea that has only gained strength since Narendra Modi, an early protégé of the group, was first elected prime minister in 2014 through the RSS’s unofficial political wing, the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP). Caravan, meanwhile, has embraced a mission of protecting India’s tradition of democracy and religious pluralism, more often than not through exhaustive investigations into the RSS and its affiliates.

For the most part, confrontations between the magazine and the nationalist organization have remained in the courts and online. This should go without saying in just about any democracy, but lately there has been concern that a story could lead to actual violence.

In one incident, a few months before Modi’s election, Caravan published an explosive cover story based on a series of interviews with Swami Aseemanand, a right-wing Hindu monk who claimed that the RSS had been aware of his plans to bomb multiple venues targeting Muslims from 2006 to 2008, attacks that left more than a hundred dead. The day the story was published, around one hundred RSS protestors gathered outside Caravan’s offices, waving the party’s saffron flags and carrying signs reading “BAN ANTI-HINDU CARAVAN” as they set fire to copies of the magazine.

That morning, Jose received dozens of calls, to both his office and cell phone, from anonymous numbers: “We are coming for you,” several callers told him; another screamed “motherfucker” and threatened, vaguely, to “stop” the magazine. Police and private security arrived to prevent protesters from entering the building, while television reporters covered the chaos outside. Since the protests, menace toward the magazine has persisted in the shadowy, nebulous way that most journalists are pressured these days: online trolls, breaches of its computer network, and, in Caravan’s case, a handful of defamation lawsuits.

Living under a constant, simmering threat is, for Jose, evidence that he’s doing something right as a journalist. Nearly every day, he receives ominous online messages that accuse him of being “rabidly anti-Hindu” or “anti-national” or a “Christian bigot” or “DEEP STATE JOURNALIST VINOD K JOSE … FROM COMMIE COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY.” Jose is almost certain that his cell phone is bugged, not to mention the entire Caravan office. Six months after Modi first became prime minister, Jose fired his personal driver, who had been acting suspiciously; friends, meanwhile, began warning him to take different routes to work each day, just in case.

Image: Courtesy The Caravan

As tense as the atmosphere was for India’s free press following Modi’s first election, things have only worsened since. A number of editors claim to have been bullied by Modi loyalists seeking to remove online coverage that was critical of the BJP; newspapers that have published negative stories have been penalized financially, often through the loss of government-funded advertisements. At the same time, journalists at mainstream outlets have become ever more explicit, if not boastful, about their political connections. When Arun Jaitley, the BJP’s finance minister, died in August 2019, a reporter from one of India’s largest television channels, Times Now, tweeted: “I’ve lost my Guiding Light my mentor. Who will I call every morning now?”

Most sinister of all, the censorship of Modi’s critics has escalated into violence. Since he first came into office, twelve journalists have been killed because of their work, and at least nine have been imprisoned. In 2017, the prominent journalist and editor Gauri Lankesh was gunned down in the early evening in front of her estate in Bangalore. Lankesh, an outspoken feminist and human-rights activist famous for her left-wing tabloidesque attacks on Hindu-nationalist figures, was a close friend of Jose’s — the two had worked together covering contentious riots in Goa in 2005. Her death confirmed the seriousness of what Indian journalists were up against under the new regime. Not long after, a right-wing nationalist followed by Modi on Twitter posted: “One bitch dies a dog’s death all the puppies cry in the same tune.”

After Lankesh’s murder, Jose began implementing protocols for Caravan’s staff to follow: All communications are now handled on encrypted channels, such as ProtonMail or Signal (WhatsApp, he believes, is compromised in India), and reporters working on sensitive stories are instructed to be especially vigilant in protecting their sources. And yet, like almost everyone else I spoke with at Caravan, Jose wasn’t all that interested in talking about the government’s intimidation. “You can’t slow down your work just because something has happened. There are certain requirements of the job.” Rather, he was eager to know whether I’d been following their coverage of the mysterious death of Indian special-court judge Brijgopal Harkishan Loya (twenty-eight stories and counting), or whether I’d read their cover story about how the RSS had been systematically infiltrating India’s intellectual spaces.

His phone rang — a source with a tip. A rumor had been circulating through Delhi’s high-profile social circles that, in anticipation of the upcoming national election, the BJP was using “chips from Silicon Valley” to meddle with polling machines in the state of Uttar Pradesh. The implications, if true, meant major election fraud in the world’s largest democracy. Did they want to look into it? Jose glanced at me, almost helplessly. He had never imagined that his little magazine, with limited funding, a staff of 38 people, and an inclination toward fiction and poetry, would ever become one of the only outlets breaking major, sensitive political stories in a country of over 1 billion people. “This is the job for leading newspapers and weeklies, but nobody was stepping in to cover them,” he told me after hanging up the phone. He couldn’t help but feel obligated. “How are you supposed to respond to stories which are journalistic but nobody else is doing them?”

That Caravan has come to occupy such a critical place in India’s media landscape was hardly predictable. In its first iteration in the 1940s, Caravan was a leading general-interest magazine for India’s intellectual elites before it shut down in 1988. For the next two decades, the magazine lay dormant, until Anant Nath, the grandson of the founder of Caravan’s publisher, Delhi Press, decided to revive it. At the time, Nath had recently finished his master’s degree in political science at Columbia University, and he saw an opening in the South Asian media market for a magazine that could cultivate India’s rich literary scene. “The idea was very simply to have a magazine on politics, art, and culture, with a liberal bend of mind,” Nath explained when we met last spring, in an airy, modern corner of Caravan’s offices. “I didn’t want it to be newsy or overtly political,” he added, but beyond that, their only agenda was to “not be closed-minded.”

Caravan officially relaunched in 2010, a time when India’s prolific media industry was dominated by what Indian journalist P. Sainath dubbed “feel good” journalism. These stories portrayed India’s economic rise with great enthusiasm while neglecting the harsh social and economic inequality afflicting the majority of its population. “What this actually meant was that you couldn’t put the impoverished majority on the front pages,” Siddhartha Deb, the prolific author and a contributing editor to Caravan, told me. “Vinod was completely against this. He and Anant were interested in accurate reporting and research. They were concerned with stories ignored by the mainstream.”

At the time, longform journalism was relatively unheard of in India. A few magazines, such as India Today, Outlook, the Week, and Tehelka, had been around for years, but they were newsweeklies similar to Time or Newsweek. Caravan, on the other hand, was meant to be a literary experiment. In his original “Vision Document,” drafted in 2010, Jose declared that Caravan’s editorial temperament was to take its cue from the American wave of New Journalism pioneers such as Tom Wolfe, Gay Talese, and Dick Schaap. Jose envisioned creating a home for a new brand of Indian writer, to be read by India’s educated “pop-intelligentsia.”

In this respect, Caravan’s revival was a success. The magazine’s earliest writers and contributing editors included some of South Asia’s literary giants: Pankaj Mishra, Arundhati Roy, Siddhartha Deb, and Fatima Bhutto. “Caravan was, and remains, wholly distinctive in the English-language media in India,” Mishra wrote to me recently. “It helped focus attention on many forgotten writers.” Within a few years, Caravan was distributing around 25,000 copies across the country; its website now gets over 1.5 million page views monthly.

Image: Courtesy The Caravan

Much of Jose’s early inspiration behind Caravan’s editorial design didn’t come from inside the newsroom, but from the American journalist Matthew Power, who was a contributing writer to Harper’s magazine and was well-known for his peripatetic, character-driven stories filed from obscure corners of the world. Jose met Power in Delhi in 2002, and the two became fast friends, “like bread and butter,” Jose says. Power introduced him to magazines such as Harper’s, The New Yorker, and the Believer. Jose was stunned by what went into their production. “I thought, ‘This is a new school of journalism and a highly laborious exercise,’” Jose told me. “I thought, ‘Why doesn’t my country have anything like this? Why don’t we have space to do longform?’”

For India’s young intellectuals, the magazine quickly became an essential venue, cutting an anomalous figure in a media environment rife with sensationalism and government flattery. “Caravan is this lonely but incredibly brave beacon in this unending toxic sewage, fake news, social media violence,” said Deb. “It has been going it alone as far as Delhi is concerned.” It was neither entirely a literary magazine nor a newsweekly nor just a book review, but a combination of all three in the form of a periodical that, as Mishra put it to me, “analyze[d] the news with adversarial politics.”

When I arrived at Caravan as an intern in 2014, those “adversarial politics” were ramping up in response to the rise of the BJP. All the while, the magazine retained a quirky sense of humor and a conspicuously literary sensibility. I sat in the “intern corner” — a lonely, dusty space adjacent to the sales department where I and a couple of other interns helped fact-check and copy edit while stealing outside several times a day for unauthorized chai tea breaks. Most of the time, the office was monastery silent. A sign in Hindi hung over our heads: “SITTING IDLE IS NOT ALLOWED.” The content in those days was a balance of the idiosyncratic and the intellectually rigorous, with book reviews on the likes of Gabriel García Márquez (“a many-sided genius”) and Rabindranath Tagore (“a poet in full possession of his voice”) nudging up against critical think pieces about how to “untranslate a translation” and dispatches from countries such as Peru and Turkey and Cambodia, all running alongside massive political features for which the magazine was best known.

Modi’s rise had marked a shift in the magazine’s identity. “I don’t think you can plan it,” Nath told me, almost apologetically, as if he were nostalgic for a time when Caravan was better known for its book reviews. “But the magazine takes its own shape, and sometimes without very conscious thinking. In the last four years, the case has been that much of the mainstream media has not been objectively critical of the government.” Caravan began to focus almost exclusively on its political investigations, to the point where, for a self-reported “journal of politics and culture,” its cultural coverage began to feel ancillary. “Caravan’s arrival meant that the amnesiac journalism of the mainstream wouldn’t be the norm anymore,” Amitava Kumar, an Indian novelist and professor at Vassar College, told me. “Over time, however, a different aspect has emerged. At first I had thought that what Caravan would make possible was stories that ran to, say, 5,000 or even 8,000 words. It has done that. But the real strength is that their journalists have done deep, investigative stories. It seems they write a Watergate exposé in every damn issue.”

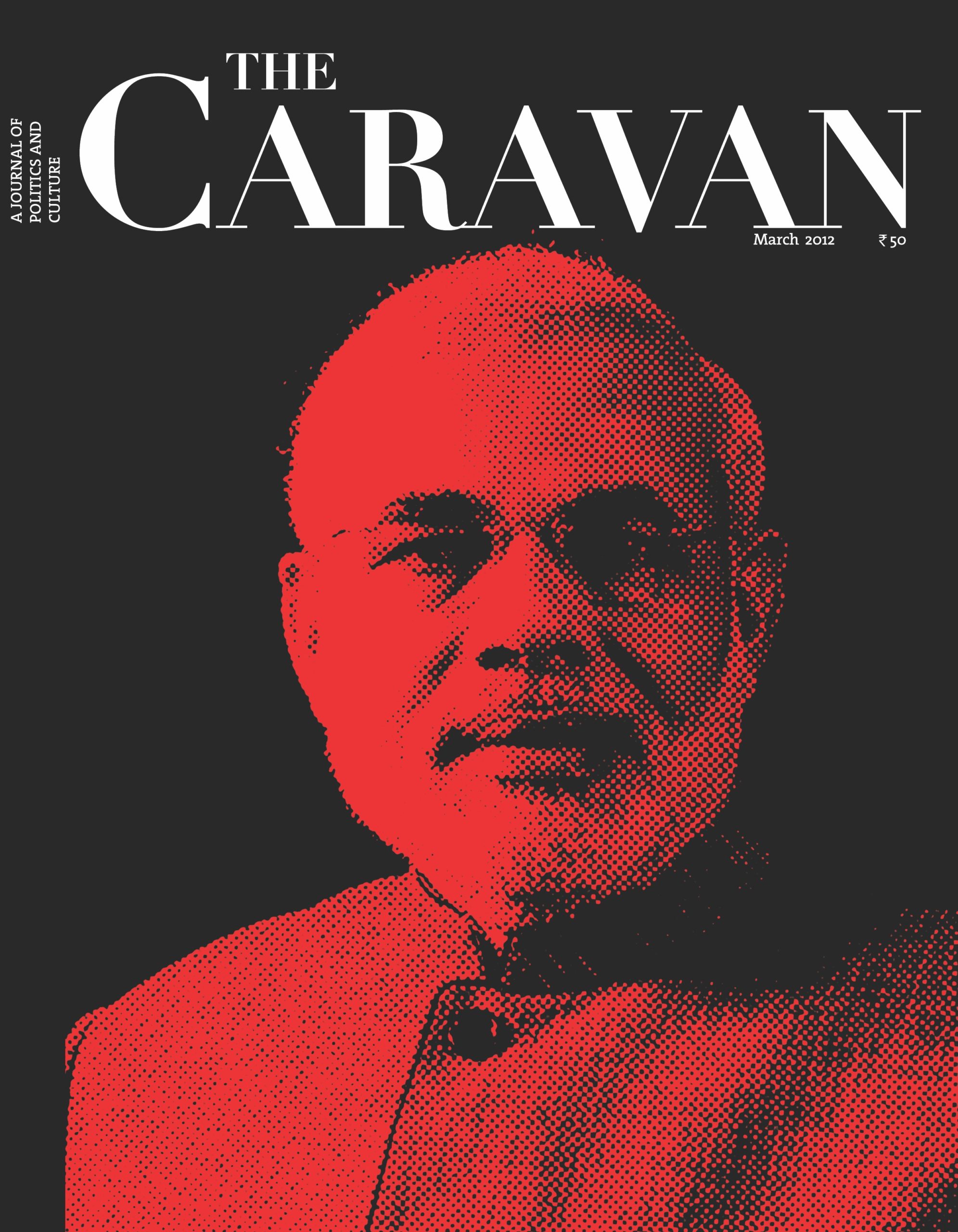

One of the best known of those features was written by Jose in 2012 — an eighteen-thousand-word profile of Modi, a star of the BJP who was rumored to be considering a run for prime minister. The article traces Modi’s political evolution, beginning at age eight, when he volunteered to join an RSS training camp in his hometown in Gujarat, to his ascent as one of the BJP’s leading figures. At the same time, the story exposed the inner workings of one of the most powerful political machines in India’s modern history. “The story of Narendra Modi,” Jose wrote, “is also the story of a series of organizations under which he was nurtured and trained,” the most important of which, he argued, was the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh.

According to Jose, to understand Modi’s rise is to understand a history nearly 100 years in the making — one that begins with the birth of the Hindu-nationalist movement in 1925, when an Indian doctor named K. B. Hedgewar founded the RSS. Hedgewar was concerned that the Hindu identity — which he saw not just as a religion but as an entire race — needed to be protected, purified, and preserved from other religions, and believed India’s Muslims and Christians were actually descendants of Hindus who had been converted to their respective religions by force.

A self-proclaimed admirer of European fascists, Hedgewar soon established military training camps in his hometown of Nagpur, in central India, in order to tutor young Hindus in combat techniques using swords, trishuls (three-pronged spears often seen in Hindu mythology), explosives, and gas cylinders. After Hedgewar died, in 1940, the group’s new “supreme director,” Madhav Sadashiv Golwalkar, maintained the RSS’s extremist views, writing glowingly of Nazi Germany in his popular manifesto, “We, or Our Nationhood Defined.” “To keep up the purity of the Race and its culture,” Golwalkar wrote, “Germany shocked the world by her purging the country of the Semitic Races — the Jews. Race pride at its highest has been manifested here. Germany has also shown how well-nigh impossible it is for Races and cultures, having differences going to the root, to be assimilated into one united whole, a good lesson for us in Hindusthan to learn and profit by.” To Golwalkar, India was not a pluralistic, religiously diverse country but “Hindusthan”: To him, Muslims and Christians were godless “invaders.”

In 1947, after three centuries of oppressive foreign rule that led to intense anticolonial backlash, the British government clumsily and hastily ceded control of the subcontinent, granting India and Pakistan their long-sought independence. Violence between Hindus and Muslims had been brewing for decades, such that by the time Partition became official, what should have been a rejoiceful night became, in a matter of hours, the beginning of a bloodbath during which an estimated 2 million people were killed. It did not take long for the two newly formed nations to adopt antithetical ideas of governance: Following a resolution endorsed by the All-India Muslim League party in 1940 for the creation of a separate Muslim-majority state, Pakistan declared itself an “Islamic Republic.” India’s founders, on the other hand, worked hard to maintain a sense, at least in theory, that it would be an egalitarian nation of Muslim-Hindu harmony with secular values.

The RSS never accepted the Indian constitution. Five months after independence, 78-year-old Mohandas Gandhi, India’s spiritual leader whose lifelong mission was to achieve self-rule for the subcontinent and broker peace among India’s sparring religions and castes, was assassinated while walking to a prayer meeting in New Delhi. The gunman, Nathuram Godse, a member of the RSS, surrendered to the police immediately, and subsequently used his trial as a political platform: Gandhi was “constant[ly] and consistent[ly] pandering to Muslims,” Godse bemoaned, which in turn had caused the “vivisection of the country, our motherland.” In response to Gandhi’s death, India’s first prime minster, Jawaharlal Nehru, temporarily banned the RSS, arresting more than 20,000 members. “But for decades thereafter,” Jose writes, “it retained the spirit of an underground organization.” Today the RSS has declared itself to be the world’s largest “social organization dedicated to Indian resurgence,” with an estimated membership in India of around 6 million.

Ten years after Indian independence, Modi joined the RSS. It only took a short while for him to rise through the group’s ranks, rejecting the arranged marriage his parents had set up for him at age 13 to devote himself instead to the austere and grueling life of an RSS pracharak — that is, a celibate “foot soldier.” In 1987, eager to take on a more powerful role within the group, Modi moved over to the BJP, eventually becoming chief minister of Gujarat in 2001. He was 51 — a lifetime dedicated to the organization.

Modi was well-known by the time Jose began writing about him. Jose’s task, then, was to go beyond the headlines and provide readers with a full psychoanalytic portrait — “an effort,” as he put it, “to understand the thought process of the man himself.” Reporting in Delhi and Gujarat for nearly a month, and conducting more than 100 interviews that included sources inside the RSS and BJP, Jose meticulously documented the forces that had brought Modi to power — and the ones that influenced his complicity in one of the most tumultuous events of his career: the 2002 Gujarat riots, a three-day pogrom against the state’s Muslims that left more than a thousand dead. Largely organized by the RSS, mobs of Hindus took to the streets in gruesome retaliation against Muslims who they believed were responsible for a fire in a train car that killed 58 Hindu pilgrims. As Jose wrote, Muslim women were raped and then burned alive; men were “cut to pieces.” Children, too, were butchered. A prominent Muslim politician, Ehsan Jafri, was “stripped and paraded naked before the attackers cut off his fingers and legs and dragged his body into a burning pyre.”

To this day, Modi has not shown any public remorse over the killings. Instead, immediately after the incident, he organized a Hindu-nationalist rally that seemed only to galvanize his support in the state. Later, when asked by a Reuters reporter whether he regretted the violence, Modi deflected. If “someone else is driving a car and we’re sitting behind, even then if a puppy comes under the wheel, will it be painful or not?” Modi said. “Of course it is.”

The diplomatic consequences of the Gujarat riots for Modi were calamitous at first. Both the American and British governments denied him a travel visa for nearly a decade. And even within his own party, a small number of more moderate BJP leaders voiced their concerns, both internally and publicly, about Modi’s possible hand in the violence. But, as Jose discovered, the BJP waged a successful and aggressive campaign to transform Modi’s image. Any BJP leaders who’d voiced criticism of Modi were systematically removed from the party — including Modi’s former revenue minister, Haren Pandya, who was shot dead in Gujarat in 2003. A month after Jose’s profile was published — and about four years into its own investigation of Modi’s role in the riots — a Supreme Court-appointed team (headed by the former director of the Central Bureau of Investigation) concluded there was insufficient evidence to charge Modi with a crime.

Published as the cover story in Caravan’s March 2012 issue to mark the 10-year anniversary of the Gujarat riots, which had largely faded from public memory, The Emperor Uncrowned triggered an intense debate about Modi’s political rise. The article was picked up both nationally and internationally, including by The Washington Post, The Wall Street Journal, the Guardian, Le Monde, and The New York Times, whose headlines later that year began to raise a new question: “Who is Narendra Modi?”

It didn’t take long, however, for Modi to revitalize his image. By 2014, Modi was elected in a sweeping victory, and a year later Time magazine devoted a glowing cover story to the new prime minister. The phrase “Why Modi Matters,” accompanied by a photo of a full-bodied Modi politely standing in a yellow kurta, the faint trace of a smile on his face, adorned the cover of the issue published in May 2015. It projected Modi as India’s answer to development and economic reform — a saint who would bolster India as Asia’s newest superpower. Not long after Time’s article came out, Sagarika Ghose, an Indian news anchor at the leading channel CNN-IBN, hosted a segment on Modi. In her right hand, she held a copy of Caravan’s cover story, and in her left, a copy of Time’s profile, as she asked the cameras: “Which Modi is the real Modi?”

By the end of his first year in office, it became clear that only one of those two Modis would emerge. The BJP’s consolidation of power coincided with the widespread silencing of the Indian media. Major news outlets, once critical of the government, suddenly diluted their criticism of it — and those that didn’t have been punished for it. As Dexter Filkins reported in The New Yorker, NDTV, one of India’s largest and most reputable television news networks, laid off a quarter of its staff of around 1,600 employees after the government pulled its advertising funding. A year earlier, Mukesh Ambani, Modi’s friend and the richest man in Asia at the time, acquired CNN-IBN. Ghose’s segment — along with most of the critical coverage of Modi — disappeared from the channel overnight.

“It’s the worst time for journalists,” Atul Dev, one of Caravan’s staff writers, told me when we met over lunch in New Delhi last spring. It was sweltering outside, the sort of heat that cast a lethargic spell. National elections were playing out energetically in all corners of the country. Modi had been appearing in a new city every few days with India’s mainstream media rapturously in tow. Dev compared what journalists were enduring in India today to the Emergency, a two-year span in the 1970s when Prime Minister Indira Gandhi suspended civil liberties — including censoring the press and imprisoning journalists at random. “But see, the Emergency was all out in the open, it was declared,” Dev explained. “Here we have a situation in which every institution seems to have been sabotaged from behind the scenes. And it can’t be fixed — unless it’s exposed first.”

Two-and-a-half years ago, Dev was assigned to work on one of India’s biggest stories, which the magazine had recently broken with a freelance reporter named Niranjan Takle: an investigation into the sudden death of Brijgopal Harkishan Loya, a special-court judge appointed to cases from India’s Central Bureau of Investigation, who reportedly suffered a heart attack while presiding over the murder trial of Amit Shah, Modi’s closest advisor. The story quickly became what The New York Review of Books described as a “scandal within a scandal within a scandal” — a debacle mired in secrecy and government cover-ups.

To report the story, Dev made several trips to Nagpur, home to the RSS’s national headquarters, often changing hotels for his own protection. Over the next five weeks he filed several stories, including one that showed how the records of Loya’s stay at the government guesthouse where he allegedly died had been manipulated, followed by another story in which a top forensic expert confirmed that Loya’s medical records showed possible trauma to the brain as well as possible poisoning. During his reporting, Dev was constantly on edge, increasingly paranoid. One day, during his third trip to Nagpur, he was walking through a neighborhood trying to track down a source when a man on a scooter pulled up next to him and, veiled behind the visor of his helmet, warned him in Hindi: “Go back to Delhi.”

Image: Courtesy The Caravan

The Nagpur-based reporting, which was soon transferred to another Caravan staff writer, Nikita Saxena, was grueling — a “glorified fact-check,” as Dev put it, “of everything being put out by the government, the newspapers.” While Loya’s death had been officially attributed to a heart attack, Caravan’s team, bolstered at that point by a large number of reporters working on different strands of the story, unearthed a number of facts that, by and large, discredited the government’s narrative: According to Loya’s family members, he’d been offered a bribe of $15 million to acquit Shah; what’s more, reporting revealed that Loya’s clothing was stained with blood; no one working at the guesthouse where Loya had been staying had heard an ambulance arrive that night; even the postmortem report had been manipulated by a doctor connected to the BJP.

When Caravan published its first story on Loya in November 2017, it was largely ignored by India’s mainstream news outlets. But it was shared virally among lawyers, activists, and journalists and was picked up by regional newspapers. Meanwhile, the State Intelligence Department of Maharashtra — the state in which Loya resided, worked, and died — began an investigation of the matter. Caravan’s Loya coverage also prompted a number of petitions to pressure the Supreme Court to open an inquiry into his death.

In an attempt to debunk Caravan’s narrative, one of India’s largest newspapers, the Indian Express, published a story in response quoting two high-court judges who claimed to have been at the hospital when Loya died as saying, “There was nothing about the circumstances of the death to raise any suspicion.”

Caravan followed up with more than two dozen stories. Saxena spent six weeks in Nagpur, tracking down all employees past and current who had been working at the government guesthouse where Loya was said to have been staying the night of his death. “There was not a single testimony of someone who recalled seeing the judge during the time that he was staying there, or remembered hearing of a high-profile guest who had suffered from a heart attack and subsequently died during his stay there,” Saxena explained. “That was very surprising to us because it also happened that the room Loya was said to have been staying at was very close to reception. I think towards the second half of my reporting I’d go back there almost every day. That was the sort of attention we were paying: To say, is there any way we could get this wrong?”

In April 2018, Saxena went with Dev to India’s Supreme Court to hear whether it would finally open an independent investigation into Loya’s death. Saxena assumed, at the very least, that the court would open an inquiry based on the new evidence Caravan’s reporters had turned up. Instead, the court pronounced that Loya had died of natural causes, and that there would be no further investigation. “There was just this stunned silence,” she recalled. “I don’t think anyone knew how to react.”

The Loya debacle was one of the most robust examples of the extent to which India’s Supreme Court had fallen under the influence of the BJP government. At the same time, the Loya coverage signaled a turning point for Caravan. When the magazine published Jose’s profile of Modi back in 2012, he and the staff had hoped it would have a concrete impact on the nation’s political future. “I realized early on very few people realized the danger of Modi,” Jose said. “A lot of people had hoped Modi would use the RSS, come to power, then become this liberal who they’d love to work with.” Instead, Modi has embraced his role as a sanitized representative of the party’s agenda, running the country with an outspoken fidelity to India’s Hindus. By the time the Loya scandal became a national flashpoint, a new reality had sunk in. Whereas Jose had once warned about the peril Modi presented to Indian democracy, now, eight years later, the magazine’s reporters were resigned to charting, like scientists, that democracy’s demise.

It was closing week at Caravan’s offices, with national elections just weeks away, and the magazine was understaffed and overwhelmed. The space was dank and shuttered, separated into cubicles by narrow glass panes that did little to create a sense of privacy, with shades pulled over the windows to shelter the room from the deadening heat. I felt like I had happened upon a cell of clandestine academic operatives, with stacks of philosophy and literature books and magazines piled next to desktop computers. In the back row of the office, an intern was reading J. D. Salinger’s “Nine Stories” with his feet propped up on the desk.

With the campaigns in full swing, Modi’s face seemed to be all over India. At the magazine, the election played in the background like the static of a broken television. Jose had recently created a project for the fact-checkers and interns — the “Modi Meter” — in which hundreds of promises he’d made in a 2014 election manifesto were rigorously fact-checked and rated based on whether or not he had followed through. The project also included a map, titled “Hugs,” that marked everywhere Modi had chosen to hug political leaders on his 57 trips abroad, complete with photos of him embracing such heads of state as Presidents Trump, Erdoğan, and Putin. At the bottom of the map, the staff had rendered a calculation of Modi’s hug probability in relation to a country’s GDP. The higher the GDP, they found, the higher the probability of a hug.

The more important business that week was a hearing for yet another defamation lawsuit. Part of the reason Caravan has been able to maintain its editorial independence is because its publisher, Delhi Press, doesn’t depend on government advertising. It is buoyed instead by some 30 other popular home and special-interest magazines, which generate between 5 and 10 million dollars per year and allow Caravan to be “an editorial success, not a business success,” as Anant Nath likes to say. But the resources are not inexhaustible, and Caravan is often punished through defamation lawsuits. Over the years, Caravan had been under so many that Jose keeps a folder in his office labeled “The Defamation Files,” so as to not lose track. Their arrival in the mail has evolved into something of a Kafkaesque comedy for the staff, with lawsuits becoming something of a rite of passage for green journalists.

One day, Jose invited me to attend a hearing for the latest case, in which Vivek Doval, the son of India’s national security advisor, was suing Caravan for criminal defamation. The stakes were high: If Caravan were to lose the case, both the publisher, Paresh Nath, and a staff writer, Kaushal Shroff, would serve time in jail.

When I arrived at the Rouse Avenue court complex, a newly constructed, chamomile building where most corruption cases are tried, Jose was seated alone in the waiting area, dressed in a brimmed hat and button-down polo that made him look like he was heading to the beach. He looked relaxed. An hour later, more than half of the magazine’s staff showed up and were then ushered into a small, windowless, fluorescent-lit courtroom with four small rows of mahogany benches facing the judge.

By the time the hearing began, a crowd had filled the benches and spilled out from the door, extending their phones like lighters in the sky to record the complaints: Doval was suing Caravan for “irreparable damage” due to a short online article published a few months earlier claiming that he’d been running a lucrative hedge fund in the tax haven of the Cayman Islands, set up just 13 days after Modi’s government demonetized small rupee notes as “part of our battle against corruption.” Caravan’s lawyers delivered a concise rebuttal: The article was based on official trade documents and contained no factual inconsistencies; it had been rigorously fact-checked, and according to Shroff, Doval had ignored a list of questions sent to clarify the exact nature of his overseas business. Twenty minutes later, the hearing concluded. Caravan had to pay a bail of 40,000 rupees (about $560) on behalf of Nath and Shroff, with the next court date set for a few months later. The trial is expected to take years, if not decades, and threatens to drain the magazine of its resources. But as the staff gathered together for a photograph that day, they seemed happy. I asked Shroff why they were celebrating. “I’m on bail,” he said, signaling a thumbs-up. “I don’t have to go to prison!”

Later that day, I found Jose in his office, asleep in his chair. He’d been at his desk all night and into early morning, following up on the tip about the “Silicon Valley” chips with two mathematics professors who were looking into whether the BJP had tampered with the polling machines. It was a story he had been quietly investigating all week with his political editor, Hartosh Singh Bal. (The story, it would turn out later, never passed what Jose referred to as the “internal bullshit detector.” The numbers just weren’t adding up.)

When I sat down, he ordered his fifth coffee of the day, black, and said that he didn’t expect to get much sleep for the rest of the week. On his desk was a printed copy of Joseph Pulitzer’s 1904 essay that proposed the creation of a college of journalism, something he was studying in preparation for a commencement speech he’d been asked to give at a journalism school in southern India a few weeks later. For a brief moment, his normally tireless energy seemed to lag into exhaustion. “Things are dipping too badly, too fast,” he said, rubbing his eyes. “The decline is very evident in judiciary, media, universities, all across society.”

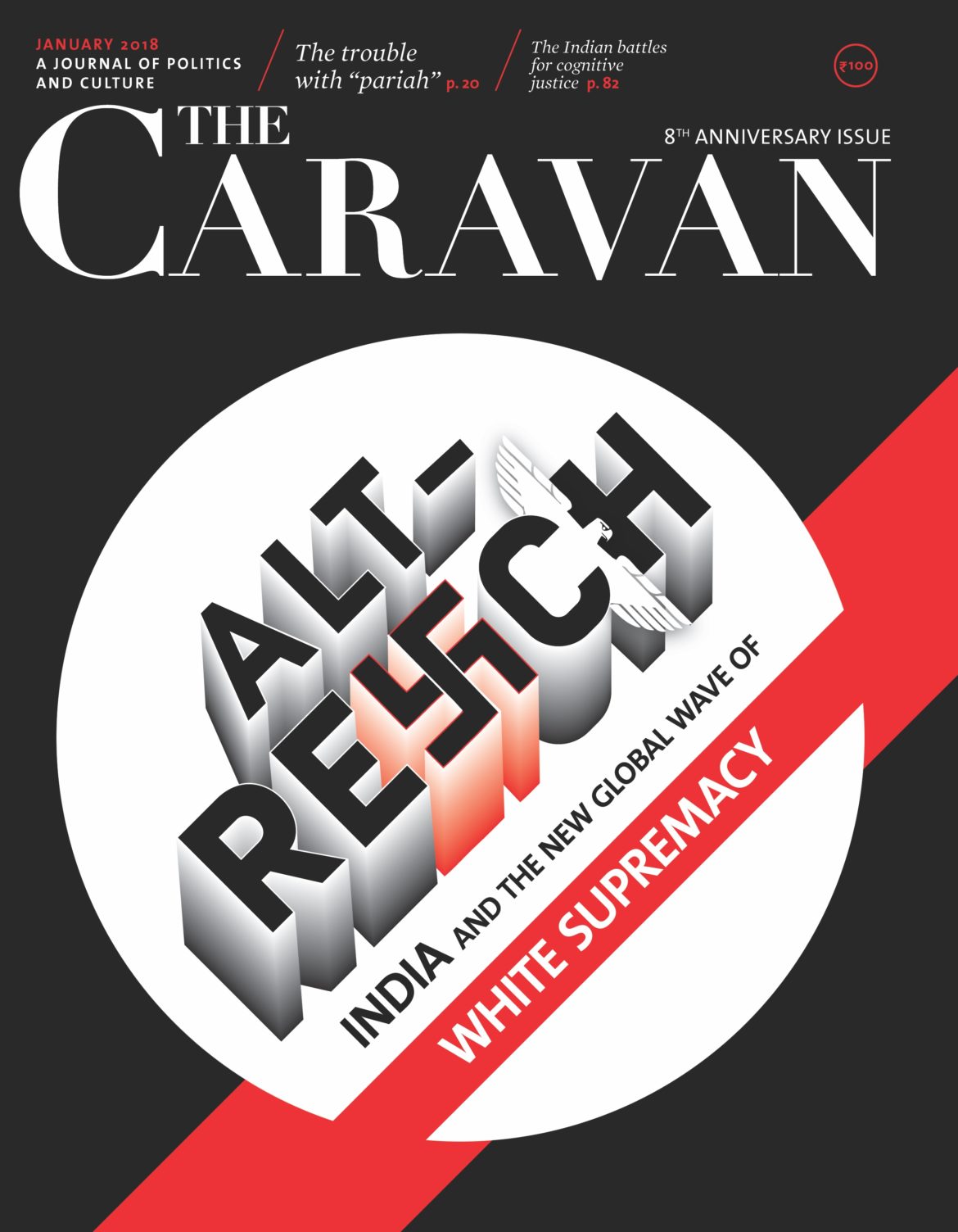

Caravan’s cover story that month was about how the RSS had been quietly targeting students at India’s most prestigious state-run university, Jawaharlal Nehru University, in order to indoctrinate them with a Hindu-nationalist agenda. To report the piece, Singh Bal had spent more than a month studying court documents, visiting the RSS headquarters in Delhi, and interviewing professors and students. The RSS, he discovered, had organized a closed-door “knowledge summit” to discuss how to bring the “true nationalist narrative” to academic spaces that remained bastions of left-wing and liberal power. The entire movement, Singh Bal wrote, was “propaganda” used by the Modi government so that “any form of dissent, or attempt to question the views of the RSS, the BJP, or Prime Minister Narendra Modi, is now framed as a threat to national integrity.”

“My worst fear is the direction the country seems to be riding,” Singh Bal explained to me later, in one of the magazine’s few semiprivate meeting spaces — a glass telephone booth of a room that stored dusty back issues. Singh Bal, who had trained as a mathematician before he became a journalist, spoke in lengthy digressions that looped neatly back to his original point. “I’ve been covering the RSS for more than 20 years; I’ve seen their growth, their takeover, their work in tribal areas, schools.” For him, the RSS’s targeting of intellectual spaces was a symptom of the “closing of the Indian mind” — a process that had been occurring, in all corners of the country, for more than a century. The strength of the RSS, he believed, would only amplify in the years to come. “Modi can be voted out,” he said. “But you cannot vote out the RSS.”

Image: Courtesy The Caravan

In May 2019, Modi was re-elected in a landslide victory whose margin stunned even his own party. The BJP won 303 seats, well more than the minimum 272 seats needed to gain majority in the lower house in Parliament. In his victory speech, Modi promised to follow through on the RSS’s long-held plans for India to identify as a Hindu nation. “You have seen that from 2014 to 2019, the people who used to talk about secularism have now gone quiet,” he said. “In this election, not one political party has been able to deceive the people of India by wearing the label of secularism!”

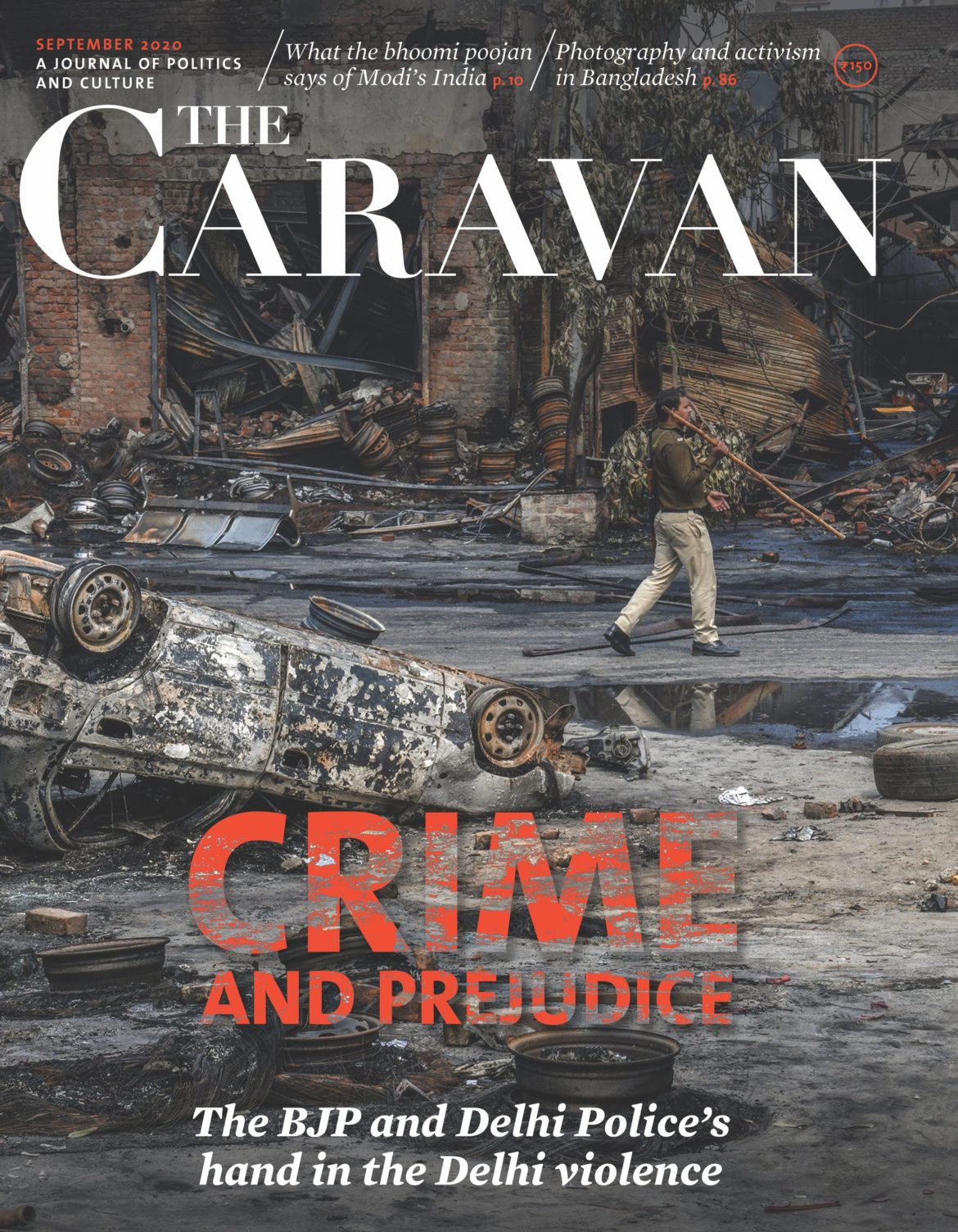

Modi acted swiftly to advance the RSS’s vision. In August, his government revoked Article 370 of the Indian Constitution, which had long protected the limited autonomy of the disputed territory of Kashmir, and imposed a complete communications blackout. Kashmiri activists and journalists went missing, hospitals and cell towers were shut down, and Army officers were instructed to shoot anybody who disobeyed curfew. That same month, the government finalized a list, known as the National Register of Citizens, of “official” citizens living in its far-flung corner state of Assam, stripping nearly 2 million Indians of their citizenship. Then, just before the new year, the Supreme Court approved a Citizenship Amendment Act, which granted a path to citizenship for religious minorities living outside India who claimed to be religiously persecuted — everyone, that is, except Muslims.

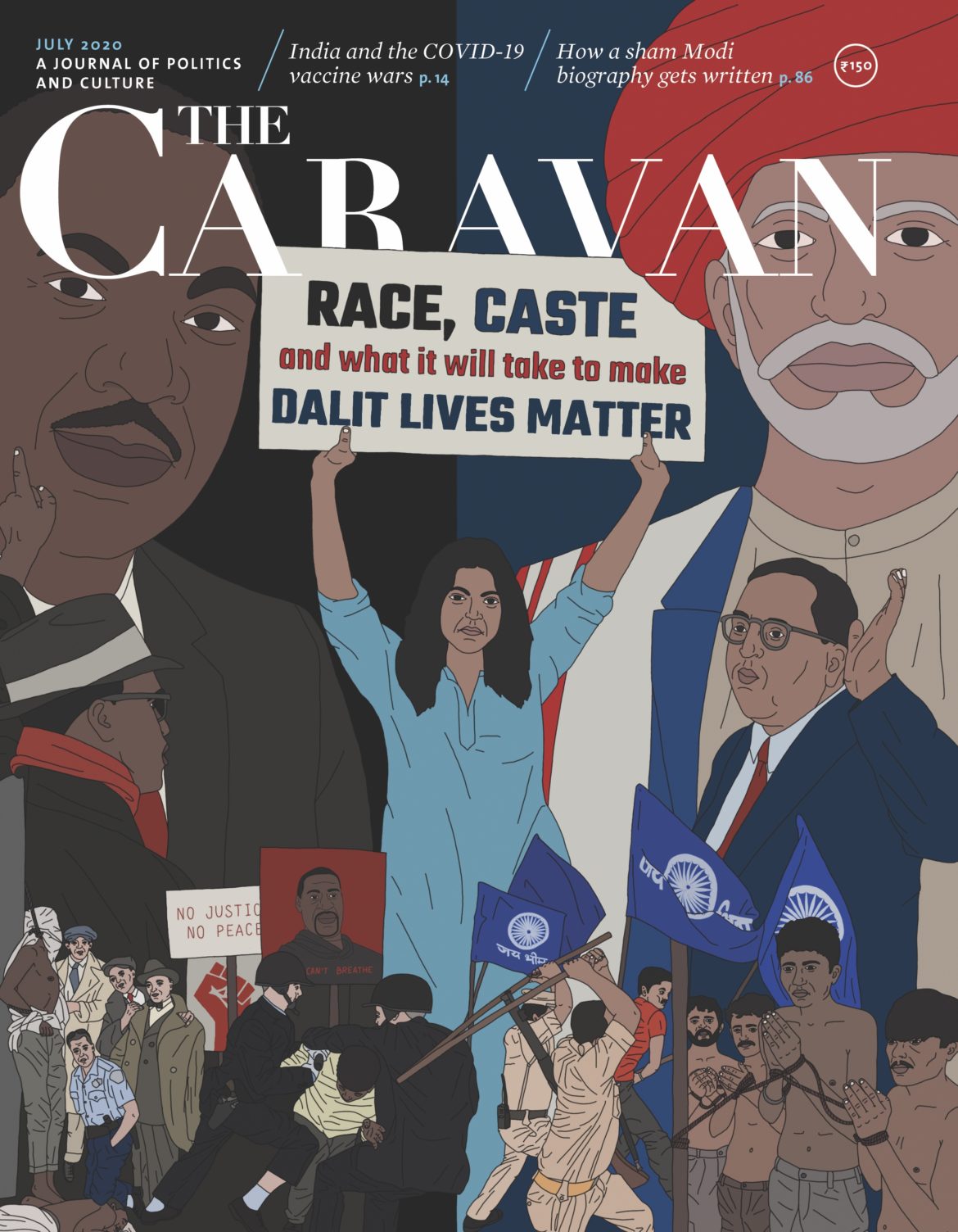

In December, protests erupted in cities across the country. The government responded with draconian measures, shutting down mobile internet services in places where there were planned protests, detaining people at random, and banning all public gatherings. When a group of students organized a peaceful protest against the recent citizenship amendment at Jamia Millia Islamia, one of the country’s prominent Islamic universities, police rampaged the campus, firing tear gas and live rounds and even raiding the library in order to beat students who were simply studying there. A few weeks later, a masked mob affiliated with the student wing of the BJP — armed with metal rods, cricket bats, and rocks — attacked leftist student leaders at Jawaharlal Nehru University, the very campus that, 10 months prior, Singh Bal had written was under threat from the RSS. These attacks, seen as an explicit reversal of India’s liberal, secular core, confirmed many Indians’ worst fears. As Arundhati Roy wrote in a Caravan cover story, “For the RSS to portray what it is engineering today as an epochal revolution, in which Hindu are finally wiping away centuries of oppression at the hands of India’s earlier Muslim rulers, is part of its fake-history project. That idea turns everything that is beautiful about India into acid.”

Then, this past spring, with the onset of COVID-19, the authoritarian potential that had already worried veteran observers of Modi and the RSS became painfully clear. India’s first case had been reported back in January, in the southernmost state of Kerala — the same day, in fact, that the World Health Organization declared a global health emergency. But Modi had said little to nothing about the pandemic for months. Instead, he moved forward with a massive public ceremony in honor of President Trump’s visit to Gujarat, where a stadium filled with more than 100,000 greeted Trump’s arrival as passionately as if the national cricket team had won the World Cup. Indian business, meanwhile, carried on as usual, exporting protective suits, gowns, and gloves, threatening to deprive local hospitals of vital resources.

On March 19, as hospitals across the country began to fill, Modi gave his first televised address on coronavirus. He called for a “Janata Curfew” and told Indians to applaud healthcare workers from their balconies just as people were doing in Italy and New York. The following week, Modi appeared on television again, around 8 p.m., to announce that, starting at midnight, the entire country — a nation of 1.3 billion people — would be under strict lockdown: All markets would be closed, all transit services suspended, no parks open, and no one permitted to walk outside. Soon after, videos began to surface on social media of police beating people on the streets — including, in one case, a doctor trying to get home from work.

The consequences of the outbreak were immediate and dire. India’s health ministry repeatedly blamed an Islamic movement, Tablighi Jamaat, for spreading COVID-19 across the country after the group held a religious gathering that became an early source of more than one-third of India’s coronavirus infections. Muslims were soon attacked across the country, often beaten by mobs. In the state of Punjab, loudspeakers broadcast from Sikh temples began instructing people to stop buying milk from Muslim dairy farmers. Party officials started to warn people about the “corona jihad.” With millions of workers suddenly let go and no buses running or food available, masses of poor workers began a slow march back to their villages. It was, according to The New York Times, one of the biggest migrations in India’s modern history. Most walked for days, fleeing major cities like Delhi, toting what they could carry with them — pots and pans and blankets, oxen, and children. More than two dozen people died of fatigue and exhaustion and dehydration along the way, their corpses left on the sides of highways. Perversely, police guarding various state borders enforced the lockdown by beating people with their batons, in some cases forcing men to squat and jump like frogs as a way to humiliate them.

Predictably, India’s mainstream coverage of the pandemic was carefully orchestrated by the BJP. A day before the lockdown, Modi held an emergency videoconference with the owners and top editors of major media organizations around the country. Their reporters, he instructed them, should “act as a link between government and people,” publishing “inspiring and positive stories” about his administration’s efforts to fight the disease. Afterward, a number of editors publicly thanked the prime minister on Twitter for, as one put it, his “strategic clarity on how to move forward.”

Caravan’s editors were not invited to the meeting. Not coincidentally, the magazine has been one of the few places — along with a couple of other online outlets such as the news websites the Wire and Scroll — that have continued to cover the epidemic critically and objectively. One of Caravan’s bigger stories uncovered how the Modi administration had failed to consult a special task force appointed by the Indian Council of Medical Research, comprising more than 20 leading scientists from across the country, before making the decision to impose a nationwide lockdown. In response to the article, the government’s press office tweeted: “Do not Fall for Fake and Baseless media reports,” adding the imprint of a red stamp reading, “Fake Fake Fake.” By May the daily death toll had reached more than 100 people, with the number of reported infections totaling about 50,000.

“Where’s it all headed?” Jose asked as we spoke over WhatsApp recently. “To a lot of destruction, a lot of tragedy.” He spoke slowly, amplifying the space between his words.

I asked him if he felt worn out, or frustrated by the fact that Caravan’s investigations seemed to be ending up in a media vacuum, rarely making a difference in government policy or even making a dent in Modi’s popularity.

“Things could get worse from here. It’s sort of a Gramscian thing of pessimism of the intellect; optimism of the will,” he said abstractly. “Crisis could lead to decay. History shows us that power remains static. Empires have fallen; crowns have been thrown down. Now, the RSS is the state. The building you see behind me is the state.”

He turned his phone’s camera to face the view behind him. The New Delhi headquarters of the RSS had grown since I’d last seen it, almost a year earlier, a pair of concrete towers reaching toward the white haze of the morning sky. The buildings would be able to house more people, Jose estimated, than India’s Parliament, the president’s house, and the prime minister’s house combined. Jose held the camera up to the window to show me a closer view. The towers dominated the frame as the camera lingered there in silence. Then, abruptly, Jose circled the camera back to his office — its papers, file cabinets, a framed photo of The Washington Post’s Nixon resignation — and the buildings disappeared from sight.

This article first appeared in The Virginia Quarterly Review and is reproduced here with permission from the author. This story was supported by the Pulitzer Center.

Additional Reading

A Small Publication in India Plays a Big Role in Citizen Matters

Pandemic Accelerates Global Decline in Digital Freedom

Investigation Keeps Work of Silenced Journalists Alive

Maddy Crowell is a freelance writer based in New York City. Her work has appeared in Harper’s, The Atlantic, Lapham’s Quarterly, The Point magazine, the Christian Science Monitor, and Slate, among others.

Maddy Crowell is a freelance writer based in New York City. Her work has appeared in Harper’s, The Atlantic, Lapham’s Quarterly, The Point magazine, the Christian Science Monitor, and Slate, among others.