Photo: Wayne S. Grazio / Flickr

Just how bad is America’s political polarization? New research by the peace institute Beyond Conflict and the University of Pennsylvania shows that a quarter of both Democrats and Republicans would support policies that harmed the other party — even if they also harmed their country as well.

And how pervasive is this level of mistrust? Pew Research found that 55% of Democrats and 49% of Republicans are “afraid” of the other party.

That is something very close to sectarianism, and it’s a game-changer for journalism. That’s because this “negative partisanship” between Democrats and Republicans is causing media audiences to selectively discount or exaggerate facts presented by reporters.

In the increasingly rare cases where rival partisans receive the same information, those facts are received differently due to psychological filters like closely-held “sacred” values, tribalism, and, especially, “confirmation bias” — where people automatically favor evidence that supports their existing views.

And polarization itself has, of course, been chosen as a core business model for several news outlets.

Screenshot: Negative partisanship is now key to the business model of news sites like Breitbart.

“It’s impossible to feel curious while also feeling threatened. In this hypervigilant state, we feel an involuntary need to defend our side and attack the other … No amount of investigative reporting or leaked documents will change our mind, no matter what.” This was the grim description of the mindset of the most polarized American voters by journalist Amanda Ripley, in her Medium piece Complicating the Narratives.

As an example, two years ago, a Pulitzer Prize-winning story by The New York Times revealed that US President Donald Trump’s fortune was the product of family gifts inflated by tax avoidance schemes. The story was hailed by some experts as one of the most perfectly crafted investigative reports in history — and yet it didn’t even move the needle on persistent Republican beliefs that Trump is a self-made man.

Getting conservatives to engage with new or inconvenient facts is, by far, the greater challenge, as most Republicans and Republican-leaning independents trust only seven of the 30 most established news outlets in the US. There has also been a general 15% decline in trust in media since 2014 among this group. One-third of Republicans rely on just a single source, Fox News, for their election information. By contrast, most Democrats expressed trust over distrust in 22 of those 30 news sources, and continue to trust facts provided by journalists in general.

Worsening matters, President Trump refers to the press as “the enemy of the people.”

America’s moderate ideological “middle” — including swing voters — has been shrinking since the 1990s. But political scientists are more alarmed by a phenomenon in which Americans are increasingly rooting for the other side to lose at all costs. Known as “affective polarization,” negative partisanship has grown much faster in the US than in other Western democracies, according to recent research by Brown and Stanford universities.

So journalists probably won’t be able to influence the judgement of most hyper-partisan Americans prior to the hugely consequential US election on November 3, no matter how perfect their stories. But journalists can take steps to reach a broader audience by staying clear of stereotypes and avoiding pushing hot buttons that feed the polarization.

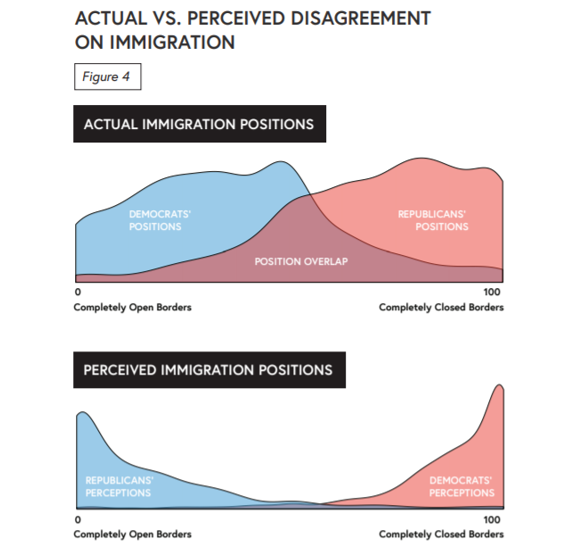

For starters, they should recognize that the press has fueled dramatic misperceptions about how many of the rival party hold extreme views. Research by the More in Common research group shows that the news media is partly to blame — with the views of Americans who consume news “most of the time” revealed to be three times more distorted than those who read it “only now and then.” Their surveys showed that the audiences of conservative news sources like Breitbart, Rush Limbaugh, and the Sean Hannity Show were the most misinformed about rival party attitudes.

Perhaps most striking is the false belief held among 49% of Democrats and 47% of Republicans that the other party dislikes them simply because of their political affiliation. In fact, recent research shows that only 18% of each party actually dislikes members of the other.

And smart adjustments might help new facts land with just a few partisan individuals, with those whose politics puts them in the shrinking middle of American politics, and some who might not otherwise have voted — and that could make all the difference.

From interviews with reporters and audience engagement editors, and a survey of research on the topic, GIJN identified a dozen techniques that journalists can use to increase the chances that audiences across the divide will at least “hear” or absorb the facts they unearth.

Complexity, Candor Can Still Break Through

“When we … offer a complex story on a complex topic, we really see that engagement,” says Emily Goligoski, senior director of audience research at The Atlantic. “It may sound like the opposite of digital guidelines for [shorter and simple stories], but the sheer amount of inbound mail we’ve gotten for our long, detailed pieces on COVID-19 shows how readers respond to complex reporting; mail saying ‘I didn’t want to read this, but I’m so glad I did.’”

Goligoski also notes that readers are annoyed by false objectivity and balance in stories, like sweeping statements that any bad behavior being reported on happens “on both sides.”

“We hear: ‘When you are honest with me about where you’re coming from, it gives me more reason to trust you, not less,’” she says.

Experts say efforts by media to seem balanced — like this NYT headline — only increase polarization and media distrust. Outraged progressives skewered the headline as woefully out of context and untrue, while some conservatives called it false objectivity. The NYT changed the headline in response, and apologized. Image: Screenshot

More complexity and transparency — and fewer trigger phrases, false equivalence, and emotional language — emerged as the most common tips on reaching polarized Americans from the interviewed experts. Also recommended: the notion that investigative journalists can be the public’s independent investigator, by simply asking “What else would you like us to find out?”

Ripley — who has written about human behavior for The Atlantic and Time Magazine — is pessimistic when asked if reporters can reach polarized Americans prior to election day on November 3, because trust, she says, cannot be rebuilt in two months.

Instead, she says newsrooms need to identify which audiences do still trust them, and ensure that their facts reach them.

“Research shows us that the more journalism people consume [in America], the worse they understand each other — we should be very worried about that,” she says. “Americans think the country is much more dangerous than it is; that their opponents are much more hateful than they are. There are huge misperceptions. At some level, journalists have to own this.”

Ripley says there are a few “tricks” to get readers to absorb facts they might not want to hear.

“One short term solution is: ‘Don’t say anything — just do an infographic,’” she notes. “We know from research that people seem to trust information that is displayed visually more than data that is conveyed in words.”

Ripley points to the work of political scientist Brendon Nyhan, an academic at Dartmouth College in New Hampshire, whose work suggests that infographics work better with confirmation bias. “We tend to trust things that we discover ourselves more than someone telling us to believe something,” Ripley says. “With a really good graphic, it feels that you are coming to the conclusion about the issue or the candidates yourself.”

“Another trick,” she adds, “is to get really curious as a reporter — because if you’re really curious about something, it is kind of contagious.”

The opposing conclusions drawn by Democrats and Republicans to the Mueller investigation on Russian election interference illustrates the problem of confirmation bias. Screenshot: Morning Consult

How Listening to Readers Can Help

But how do you engage a few more conservatives with inconvenient facts without pulling your investigative punches? David Plazas, director of engagement for USA TODAY Network newsrooms in Tennessee, says there are dozens of small ways. For example: reporters can consider the phrase “shooting deaths” as a substitute for “gun deaths,” which is a trigger phrase that can cause conservatives to disengage with a story.

The Tennessean has seen an increase in subscriptions — and evidence of greater acceptance of facts across the political divide — since it launched a dedicated “listening campaign” in 2017, including a Civility Tennessee portal, and community forums arranged by Plazas’ Diversity and Inclusion Task Force.

The outlet invited a range of community groups — from young Muslims to older gun owners — to voice their opinions and concerns, and to play a role in news choices, information gathering, and op-eds.

“In 2016, like many of my colleagues, I did not see the Trump victory happening,” says Plazas. “In 2018, I traveled the state … and I finally understood why so many people voted for Trump. It was that sense of feeling abandoned, of not being heard. We have to find new ways to listen.”

Accuracy remains paramount, and the press needs to actively correct election misinformation. But neutrality is not necessarily a central goal, Plazas says. The news conversation has been one-way for too long. “Our newspaper buildings have become fortresses that are isolated from the community. We need to be out in the spaces where people are in. This election is obviously incredibly contentious already, and I think our goal is to ask the tough questions and to listen carefully.”

12 Tips to Land Inconvenient Facts in the Minds of Polarized Audiences

- Write complex stories. While polarization dampens curiosity, complex or counter-intuitive stories can increase both curiosity and media trust. By contrast, audience engagement experts say that simple “good-guy-bad-guy” stories can irritate readers, even when they favor their rooting interest. Dr. Emile Bruneau, a neuroscientist at the University of Pennsylvania, has found evidence that complexity in narratives heightens curiosity, and that people can feel patronized by simplistic narratives.

- Recognize that extreme-sounding voters are probably sincere. It’s easy for reporters to assume that liberals who say vaccines are bad — or conservatives who say climate change is a hoax — are being dishonest or deceitful, because the evidence to the contrary is so overwhelming. But research suggests that these people, while incorrect, are probably being honest and sincere. In fact, studies show that Americans are simply far “nicer” than polls and political news suggest.

- Avoid false equivalence and “both sides” reporting. Researchers and reporters agree that audiences tend to know that phrases like “on both sides” are typically inaccurate, and designed as political cover for the outlet, rather than serving the truth.

- Be transparent. In checking President Trump’s claims about generosity to charities, The Washington Post’s David Fahrenthold broadcast his questions on Twitter, so that everyone knew what he was doing, and that all potential sources had been invited to contribute statements. The transparency in his reporting promoted bipartisan confidence in his work. Also helpful: telling audiences why reporters reach certain conclusions, and on what they don’t know, as the Los Angeles Times did with candid statements about the limits of its COVID-19 knowledge in the paper’s Coronavirus tracker.

- Avoid unneeded trigger phrases. If you have reason to use a politically loaded “trigger phrase” — such as “Islamic terrorism,” “states rights,” or “gun violence” — then use it. Otherwise, consider alternative language, as research shows that they can cause a certain percentage of polarized audiences to immediately disengage from the story. If you are conflicted in choosing between terms like “protest” or “riot,” then explain that conflict to your audience.

- Be intentional about listening. Experts say that newsrooms should actively ask their audiences: “What else would you like us to find out for you?” They say that effective listening by reporters can include sit-downs with diverse communities; asking open-ended questions rather than leading questions; and inviting sources to expand on their answers.

- Avoid generalized attribution. Attributions like “most conservatives say” or “most Democrats insist” have been found to have polarizing effects, as well as negative results for media trust. Unnamed sources should also be avoided when possible.

- Use infographics on sensitive subjects. Research suggests that visually-displayed data can cut through confirmation bias in ways that text cannot.

- Avoid zero-sum reporting. The style of journalism in which a gain of X to one group is assumed to mean a loss of exactly that same X to another group was a common failing of the 2016 election coverage.

- Read your reader comments. “One really easy thing journalists can do is read reader comments, not just on their stories but across politics stories and news platforms,” says Kristine Villanueva, audience engagement editor at the Center for Public Integrity. “It’s a way to read between the lines and get a sense of … the questions people really want answers to.”

Image: Courtesy of Coda Story

- Avoid a scornful tone. Headlines sometimes feature dismissive words like “surreal,” bizarre,” and “absurd” about partisan behavior. Research indicates that this tone can alienate potential audiences from a brand entirely. The news site Coda Story illustrated the impact value of restraint in its investigation into a Facebook disinformation campaign which claimed that 5G technology somehow spread the coronavirus. Here, the reporters had ample ammunition for scorn, in finding that the man at the center of the campaign ran the huge Facebook page from his basement, and relied on a cheap radiation detector to feel safe from electromagnetic waves. Instead, the reporters treated the man with empathy — noting that the detector was “extremely important to him” — and ran a restrained, non-polarizing headline.

- Focus on the local. We know that partisans have already firmly coalesced around their trusted national media outlets. But research shows that cross-ballot voting — where people vote for Republicans and Democrats for different offices on the same ballot — is higher in towns where local newspapers still survive. In other words, minds still can be changed with new information on local issues.

Why Reporters Need to Understand the “Us-versus-Them” Mindset

Beyond the small adjustments, experts say that it is crucial that journalists understand the collective psychology that has driven toxic negative partisanship.

This division is not about disagreement over ideas. Research indicates that Americans don’t actually disagree much more on policy than they did 30 years ago. The difference is that Americans are now afraid of the other tribe.

Social scientists explain that — despite some sharp ideological differences — a collective “you-and-me” psychology was sustained in the latter part of the 20th century by factors including major news consumption from just three TV networks, a mix of liberals and conservatives in both parties, and a common foreign enemy in the Soviet Union providing space for compromise. They say that the rise of social media and talk radio, the collapse of local newspapers, a backlash on the right to increased diversity, and the reframing of politics in terms of group values, rather than coalition interests, have since put polarization in a toxic spiral.

Worse still: mainstream newsrooms are partly to blame. During the 2016 campaign season, only about 10% of all coverage of the 2016 US election focused on policy issues. Most of the coverage dealt with “horse race” issues and personal slights between candidates. There was also a massive and surprising bias toward perceived scandal. An analysis of thousands of stories in The Washington Post and the NYT by Harvard’s Berkman Klein Center found that sentences on Democratic candidate Hillary Clinton “scandals” outnumbered sentences on her policies by four to one, while sentences on then-candidate Trump’s policies outnumbered those on Trump scandals.

One sobering poll, published last year, found news media brands represent 12 of the 15 most polarizing brands in America.

There is also evidence that these tribal fears and resentments are even more powerful than “sacred values,” which used to be considered values beyond compromise. For instance: in 2011, only 30% of white evangelicals believed that elected officials who had engaged in immoral conduct could fulfill their public duties. By 2016, this number had soared to 72%, as evangelicals leaned on fears of the Democratic party to justify their continued support for Donald Trump.

Perceptions by Republican and Democrat voters of what the other party believes on how open or closed America’s borders should be are wildly incorrect. In fact, research shows significant overlap in their positions, with only a small minority of Republicans wanting completely closed borders, and a small minority of Democrats wanting open ones. Image: Courtesy of Beyond Conflict.

“The negative partisanship and deepening polarization we are witnessing in the US reminds me of the destructive us-versus-them mindset that fed and accelerated conflict and violence in many countries around the world, from Northern Ireland to the Balkans,” says Tim Phillips, founder of the international peace-building nonprofit Beyond Conflict. “When increasing numbers of people see others across the divide as enemies and not as fellow citizens, then we are in trouble.”

However, Phillips says the “goods news” for reporters is that much of the divide is shaped by false “meta-perceptions” — what people believe others think of them — which he insists can be corrected with credible facts over time.

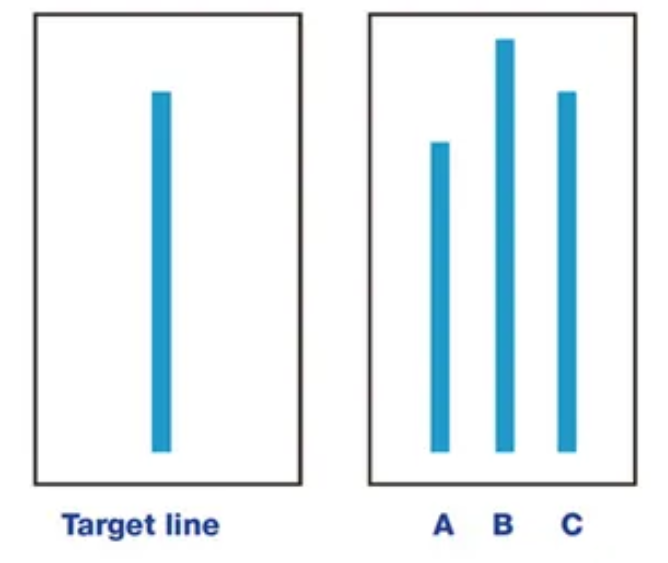

Psychologists have found useful explanations for phenomena that bewilder journalists on the polarized campaign trail — especially, why many smart, honest voters and sources seem to make blatantly wrong conclusions from clear data. The surprising power of tribal conformity is just one reason, as psychologist Solomon Asch discovered in a study in which one-third of participants consistently agreed to an obviously false conclusion reached by actors in their group.

Some 99% of people know that the correct match to estimate the length of the target line here is “C”. But 32% of people made the obviously wrong match for the target line — “A” or “B” — when actors first pretended to believe A or B were the correct answers, in Solomon Asch’s experiment on the power of tribal conformity.

Other explanations include “duelling fact perceptions” — the process that allows rival sports fans to honestly “see” two different games from the same broadcast — and negativity bias: the reason we tend to forget a compliment within hours, but stew over a criticism for days.

Ripley points to this NYT story on abortion by Nate Cohn to show how informative reporting can be done on the most polarizing of issues without alienating people on either side.

“The most straightforward interpretation may be that the polls aren’t clear because for most Americans, abortion is a difficult, even wrenching issue that they can’t easily resolve for themselves, let alone the country,” Cohn wrote. That, says Ripley, hits the mark, with “transparency and nuance and empathy. The story was not oversimplified, it was detailed; and I suspect that readers on both sides of the issue could come away feeling informed, and confident in the journalist.”

Rowan Philp is a reporter for GIJN. He was formerly chief reporter for South Africa’s Sunday Times. As a foreign correspondent, he has reported on news, politics, corruption, and conflict from more than two dozen countries around the world.

Rowan Philp is a reporter for GIJN. He was formerly chief reporter for South Africa’s Sunday Times. As a foreign correspondent, he has reported on news, politics, corruption, and conflict from more than two dozen countries around the world.