Seen any good movies lately?

Hi, I’m Matt Carroll. If you’ve seen the movie Spotlight, then you’ve seen me, or at least seen the actor who plays me so wonderfully as a newsroom nerd. It’s a great show and won the Oscar this past year for best movie.

Hi, I’m Matt Carroll. If you’ve seen the movie Spotlight, then you’ve seen me, or at least seen the actor who plays me so wonderfully as a newsroom nerd. It’s a great show and won the Oscar this past year for best movie.

If you haven’t seen the movie, it tells the story of the Boston Globe’s investigative team — Spotlight — as it unravels decades of sexual abuse of children by priests in Boston.

I was a member of the Spotlight team, when we wrote our first stories back in 2002. It started when columnist Eileen McNamara wrote about a priest who had been repeatedly moved from parish to parish, despite molesting children.

The new editor of the paper, Marty Baron, handed the story to the Spotlight team. That was pretty remarkable because it was his first day on the job.

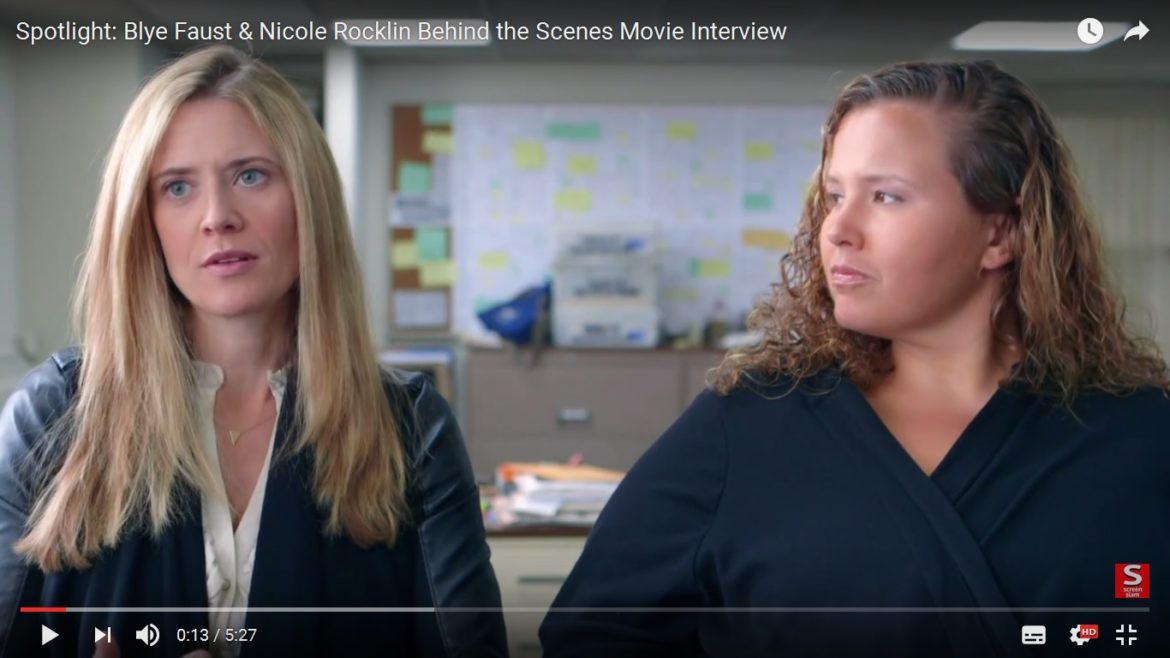

Spotlight’s Matt Carroll and his movie counterpart Brian d’Arcy in an interview about the movie based on The Boston Globe’s investigation.

On one level, the movie tells the story about the amazing courage of the survivors and how the scandal was covered up by the church. But it’s also a story about investigative reporting, and how that kind of reporting can ignite national, even international, changes.

Words have power. Back them up with deep reporting and you can have explosive stories.

That’s why we need investigative reporting. But investigative reporting is in danger, and reporters need your help. It’s in danger because the finances of the news business are crumbling. I’m not going to bore you with the details of why, but consider this:

In 1990, there were 57,000 journalists covering school boards, crime and doing investigations. Now there’s a few more than 30,000 reporters out there.

Think about that. Half as many reporters as back in 1990. That makes it tough to cover high school football, never mind do investigations.

Folks, it is a great time to be a corrupt politician in America. Let’s face it: Who’s watching the public store? We need reporters to do that. That’s one of our jobs.

Some newsrooms still have big investigative staffs. The Globe has 6 reporters, for example, 2 more than they had in the movie. But many newsrooms have cut back or given up their teams altogether. It can be easy to cut back on investigations when it’s a question of whether city hall gets staffed or not.

Let’s look at what’s involved in an investigation. An investigation is gritty, slow, laborious. We researched for months before we published that first story. Four people, months, that’s a lot of shoe leather.

And it’s expensive. The movie shows 4 people working, but over the course of the year, the team grew to about 8. What did that cost? Back of the envelope calculations put the cost at about a million. One million dollars. That’s a lot of cash for one investigation.

Look at how we spent that time. Before writing the first story, we spent months looking for people who’d been abused. One woman we tried to find was Maryetta Dussourd. I finally found her in Jamaica Plain, in Boston. I turned up on her doorstep on a cold grey day in the fall.

She didn’t have a phone, but by chance she had a cold so had stayed home from work that day. She invited me in. It was a little funny at first. Maryetta had a parakeet named Xerxes. Xerxes was out of his cage and flying all over the apartment.

I was trying to interview Maryetta, but Xerxes was a curious bird. He kept landing on my head, and on my knee — driving me a little crazy. And I kept taking notes and swiping at Xerxes. Xerxes, man, go away. Thinking back, I laugh a little bit about that bird.

But I never laugh at what Maryetta told me.

I knocked on her door and told her I wanted talk about a priest named Fr. John Geoghan. As soon as I mentioned Geoghan’s name, tears started to roll down her cheeks. She cried and talked and cried and talked, for the next 3–½ hours. She couldn’t stop.

I knocked on her door and told her I wanted talk about a priest named Fr. John Geoghan. As soon as I mentioned Geoghan’s name, tears started to roll down her cheeks. She cried and talked and cried and talked, for the next 3–½ hours. She couldn’t stop.

She was a young mother when she met Geoghan, who was her parish priest at St. Andrews. They hit it off. She invited him home to visit. Soon he was like a member of the family. She even bought him a blue Teddy bear.

She was delighted. She was a deeply religious Catholic. He was a priest, someone on a pedestal. She had seven young kids in her house — her own and the kids of a sister. She was so happy that Geoghan was there, helping with the children. He’d take them upstairs at night, put them to bed, pray with them.

Then she found out that he’d molested the children while he was supposed to be praying with them. All seven. Seven young innocent kids.

Geoghan shattered her world. Her life was in turmoil. But she stood up, she went public and told the world what Geoghan had done, one of the first victims to do so. Now at this point when I spoke with Maryetta, we were still doing research and hadn’t published any stories.

Geoghan was one of the priests we were investigating because there were so many complaints against him — eventually more than 130. We were doing what we call a “deep dive” on Geoghan, trying to get as much information as we could.

It turned out that Geoghan lived on Pelton Street in West Roxbury. Hey, I live in West Roxbury. I pulled out a map. Pelton was around the corner from my house. Literally around the corner. I walked to his house. It took maybe three minutes. The same priest who’d abused Maryetta’s kids was my neighbor.

My wife Elaine and I had 4 young kids at home — Kasey, Alex, Leigh, and Jack. They were 8 to 14 years old. Prime years for an molester. I thought I’d be sick to my stomach. We were totally rattled.

We suddenly had a much better understanding — even if it was only an inkling — of what the victims of abuse and their parents go through. What parent would not do anything to protect their kids from a predator like that?

Spotlight movie screenshot: Reenactment of Matt Carroll warning his children with a note on the fridge

I printed out a picture of Geoghan and taped it to our refrigerator, telling the kids — if you see this guy, run the other way.

It was an amazing coincidence that Geoghan lived so close. Too amazing, actually. The movie makers decided to unsensationalize it in the movie. They said no one will believe that Geoghan was a neighbor. So they turned Geoghan’s house into a treatment center instead.

Well, we had neighbors with kids. I talked with Robby — Walter Robinson — who ran our team. I asked him if I could tell neighbors about Geoghan. He said, No, don’t do it we’re in the middle of a major investigation. If word gets out, the whole investigation could be jeopardized.

My head understood what he said, but my heart didn’t. I did keep my mouth shut. But not my wife. I didn’t know until years later that Elaine said, screw that, and told neighbors to keep their kids away from Geoghan.

Our first story ran on Jan 6, 2002. Like all reporters, we hope our stories — whether it’s on the City Council or an investigation — will result in changes.

Boston Globe Spotlight team’s first front-page story which exposed the sexual abuse of minors by Catholic priests.

But nothing we had ever done prepared us for what happened next. The reaction was overwhelming. The phones and emails exploded. Hundreds and hundreds of victims reached out from all across the country, and eventually the world. We never expected anything like that.

The intense reaction was driven largely by the Internet. Remember, this is the early days of the Web. There were web sites and email, but no social media.

Newsrooms did not have a good understanding of how stories could mushroom. This was one of the first investigative stories to go viral. I don’t even think the term “viral” was in popular use at that point.

Our small team doubled in size. We ended up writing 600 stories in a year.

It was an amazing time. Those stories made a difference. The Catholic church made changes. Cardinal Law was booted from Boston, to a gilded cage in Rome. Laws were changed to better protect children. A lot of people who had been abused as children received help, counseling and money.

And we ended up winning a Pulitzer, which is very cool, no doubt about it. That was the end of round 1.

Here comes round 2. Fast forward a few years. The scandal had faded into the background, but not gone away entirely.

New scandals kept breaking in other cities and countries. We were approached by two spunky Hollywood producers, Nicole Rocklin and Blye Faust. They wanted to do a movie about our work. We kind of looked at each other and asked, Let’s get this straight: You want to do a movie about reporters talking on the phone? “I’m sorry sir, can you spell your name for me again?”

And they said, yes. They brought in a writer, Josh Singer, and a director Tom McCarthy, who also co-wrote the script. A great pair.

And they said, yes. They brought in a writer, Josh Singer, and a director Tom McCarthy, who also co-wrote the script. A great pair.

And they assembled an amazing cast. Michael Keaton. Mark Ruffalo. Rachel McAdams. Liev Schreiber. John Slattery. And the guy who plays me, Brian D’Arcy James.

And much to the surprise of everyone on the Spotlight team, they actually made the movie. It’s a heck of a movie, it really is, if you haven’t seen it.

It’s cool as much for what doesn’t happen, as what does: No gunshots, no car chases, no sex. Just two hours of people talking. It doesn’t sound exciting — but it is — and you really get the point.

So what happens after the movie comes out? Another wave of victims comes forward. More people who’d been abused courageously put up their hands and talked about what happened to them.

Those stories have stayed with me. At one point, after the first stories ran, I talked to a gentleman who was in his 80s. One day back in the 1920s — 1920s, think about that, how long ago that was — a priest drove him to a quiet spot behind a lake in New Hampshire and molested him.

This guy did OK, he led a good life, unlike a lot of others who were destroyed by booze or drugs. But still. Decades later he tells me about this terrible thing like it happened to him yesterday. He could still remember details about the wind shaking the leaves on trees and the waves on the water.

But he stood up. He wanted to to be counted. Like Maryetta. We think our team — that investigation — changed so many people’s lives. In Boston, at least 270 clergy have been accused of child sexual abuse. More than 1,200 victims have come forward.

Worldwide, the Vatican has defrocked more than 800 priests. It’s been incredibly humbling to realize we have helped so many people. Men and women have called us, telling us how relieved they were that we had listened to them and written their stories.

They had been telling their tales of abuse for years, decades in some cases, and many had a hard time finding people who would believe them.

Phil Saviano, one of the survivors, wrote: “The Boston Globe Spotlight Report rocked the environment and quickly shifted public perceptions of the clergy abuse issue.

“Suddenly, we survivors who revealed our childhood traumas found ourselves believed, even respected. We took comfort and strength in the unimagined numbers of other survivors going public.”

That’s a wonderful note from Phil. And that’s what I mean when I say: Investigative journalism can change the world.

All the people who worked on that investigation — and there were many more than are shown in the film — are immensely proud of what we accomplished. The question is: Can these types of investigations continue, when news organizations are in trouble?

Maybe they can, with our help. But they do need our help. What does that help look like? Well, it could mean reading quality journalism and ignoring clickbait. Do your homework and look for reliable news outlets.

Maybe speak up when someone talks about changing libel laws, which would make it tougher or even impossible to print stories like Spotlight.

And I hate to say this, because it sounds like an ad, but paying a few bucks a week for quality news is a good thing too. A digital subscription costs per week about the same as an extra-large coffee at Dunkins. It won’t keep you caffeinated, but it will keep you informed.

So please support quality news in some way. Because without the support of the public — that’s us — investigations that should be done, will not get done. And that could mean investigations as big and as important as the Spotlight series.

Thank you.

This post, which is a lightly edited version of Matt Carroll’s TedX Beacon talk on Nov. 19, in Brookline, Massachusetts, first appeared on Medium and is reproduced with the author’s permission.

Matt Carroll is a journalism professor at Northeastern University in Boston and was part of the Spotlight team that exposed the clergy sexual abuse of minors scandal. He is also the publisher of the “3 to read” newsletter, a once-a-week email with links to that week’s top stories about journalism.

Matt Carroll is a journalism professor at Northeastern University in Boston and was part of the Spotlight team that exposed the clergy sexual abuse of minors scandal. He is also the publisher of the “3 to read” newsletter, a once-a-week email with links to that week’s top stories about journalism.