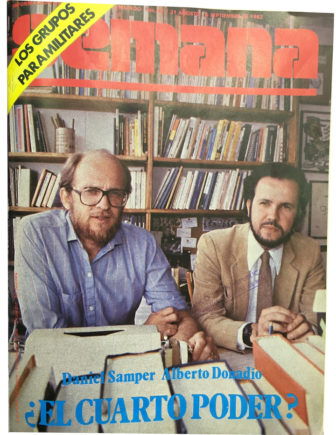

Alberto Donadío was part of Colombia’s first investigative unit and later wrote investigative books about almost every scandal in the Latin American country. Photo: Courtesy of Premio Simón Bolívar

Alberto Donadío has been called the father of the right to access public information in Colombia and one of the pioneers of investigative journalism in Latin America. Paradoxically, he is also a little known figure.

Originally a lawyer, he started out as a pro bono activist in the late 1960s, gathering information on violations of citizens’ rights and environmental crimes. He was then formally hired as one of the “three musketeers” that made up the investigative unit at Colombian newspaper El Tiempo, the first of its kind in the country. Their exposés became legendary; less well-known was Donadío’s crucial role in many of them.

After he left the paper, Donadío dedicated his life to writing books about investigative journalism. He’s written more than 10 books, involving just about every single financial and corruption scandal in the last 30 years, as well as a profile of former dictator Gustavo Rojas Pinilla, Colombia’s hidden role in World War II, and the country’s war with Peru. Sadly, most of the books are completely unknown to the majority of Colombians.

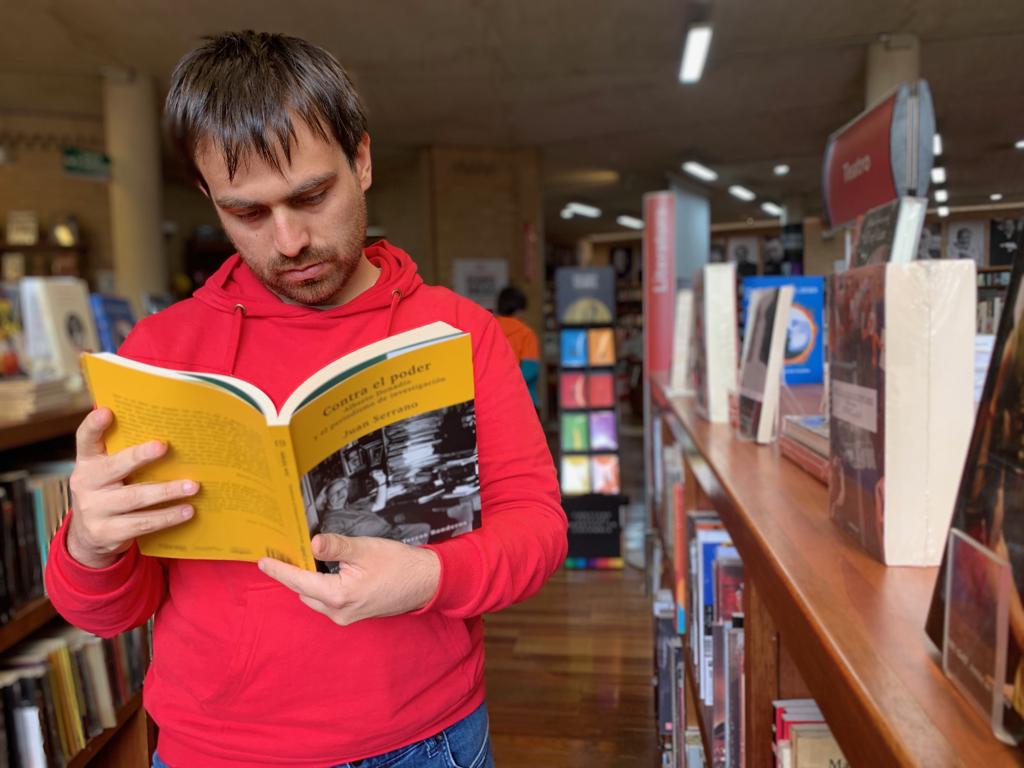

Why? Juan Serrano, a young journalist who is the producer of Podcast La No Ficción, became curious about the life and work of this enigmatic muckraker and ended up writing the book “Contra el Poder” (Against Power), which won the most recent Simón Bolívar prize, the most important journalism award in Colombia. GIJN’s Spanish editor Catalina Lobo-Guerrero talked to Serrano about his book and its main character.

GIJN: You say that Alberto Donadío, in literature, would be a cult author.

Juan Serrano: Yes … he’s completely exiled to the field of books. It’s where he’s found the freedom to touch on the subjects he wanted, without depending on the agenda of the media and without having to deal with the pressures he faced during his time at El Tiempo newspaper.

Juan Serrano’s book about Alberto Donadío, “Contra el Poder,” won the most recent Simón Bolívar prize. Photo: Courtesy of Juan Serrano

GIJN: The phrase from your book that best illustrates the position of the owners of the newspaper at the time was: “This country is not ready for Yankee style, Watergate style, investigative journalism.” Can you explain more about that?

Juan Serrano: Yes, in El Tiempo — which has always been a pro-government newspaper, it was the main newspaper and still is today — there was a journalist named Daniel Samper. He was very influenced by what was going on in the United States in the early ‘70s; he had studied there. The Watergate scandal was in full bloom, the environmental movement was also flourishing and Samper wanted to investigate like the journalists from The Washington Post or The New York Times.

He was an op-ed columnist, but he understood that if he wanted to give weight to his column, which among other things was a daily column, he needed an investigator. That man was Alberto Donadío, who started doing it for free and informally at first. He would look for information and documents and bring material for the columns that Samper wrote. That’s how he landed in journalism, first as an activist, eager to denounce ecological threats or abuses, for example, against consumers. (Some of the first abuses that Donadío discovered, for example, involved the US Consul General in the Amazon, who was trafficking tropical species.)

GIJN: How curious that investigative journalism in Colombia and the investigative unit of El Tiempo began through an opinion column by someone who already had a name. It’s interesting how they used that to their advantage.

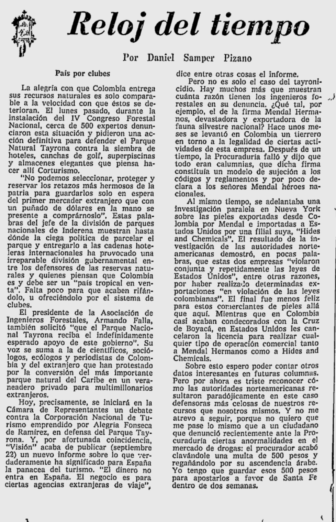

Photo: Courtesy of Juan Serrano

Juan Serrano: That’s exactly what happened. Initially, the exposés were published in Samper’s column. It was probably the most read column in Colombia, the most influential, the one with the most weight in public opinion. And I think that, in part, it was so popular because he would expose things in his column; he was serving the people. But of course, that evolved and changed when the investigative unit was created. And it’s very interesting what they did. The unit would write an article where they would reveal the wrongdoing. And then Daniel Samper would mention the investigation in his columns and would call for the resignation (of a minister or civil servant, for example) and wage those battles in public.

GIJN: That unit also began to work in a pioneering way by making freedom of information requests, using a law that I didn’t know had existed from the beginning of the 20th century, and that had been ignored or not used in decades.

Juan Serrano: Yes, Alberto Donadío — this is important to keep in mind — was a lawyer, a law student actually, because at that time he still didn’t have a degree. But he was someone who was also aware of certain trends in the United States. He knew investigative journalists there were using the Freedom of Information Act. Because he was a law student, he realized that in Colombia there was a similar law since 1913, that already gave citizens the right to access public documents, unless they were explicitly classified.

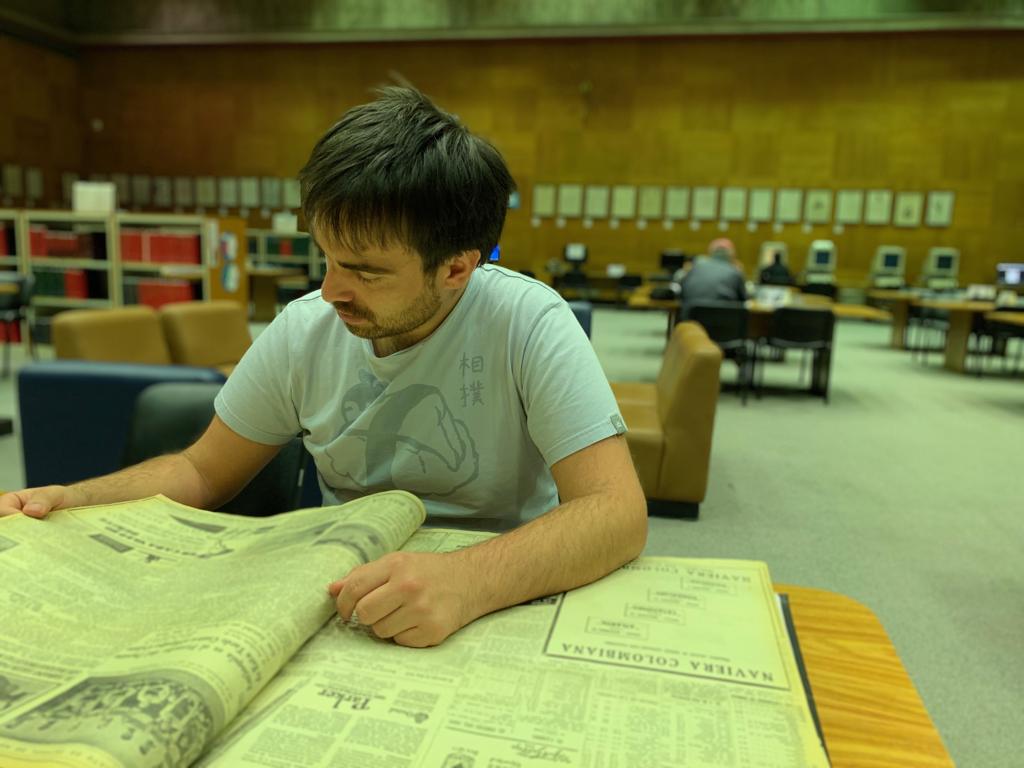

GIJN: One thing that didn’t exist in Colombian journalism either was the tradition of working with documents, of researching in the archives. Let’s talk about that too, because I was surprised to read that when Alberto decided to do a book on the dictator Gustavo Rojas Pinilla and tried to rely on historical documents, he discovered a very sad reality.

Juan Serrano: Yes, there is a total disregard in the ministries for the value that those documents may have, for the documents that a public entity produces. There are cases — this was told by Alberto and Silvia Galvis [the journalist and wife of Donadío] — when they did the book, “El Jefe Supremo” (The Supreme Boss), they found that in some public entities they had discarded the archives as old paper or had thrown them into the Salto del Tequendama [a waterfall in Colombia] or sold them to make tiles or burned them. So, there was a lack of a culture of preservation of official documents, and that is a void that any researcher who is interested in reconstructing a passage of Colombian history will encounter.

Serrano’s book is based on historical documents and interviews with Donadío. Photo: Courtesy of Juan Serrano

GIJN: What is the Record Group 59? Why were Alberto Donadío and Silvia Galvis so obsessed with researching that archive?

Juan Serrano: At the beginning of the 1980s, Donadío read an article in a magazine published at that time by the association of Investigative Reporters and Editors which talked about the National Archives in Washington, that were being underused by journalists. Historians were getting a lot out of it but journalists could also find wonderful jewels for stories in there.

So, on a vacation, Alberto and Silvia Galvis go to Washington with the purpose of getting to know that archive. They go to the front desk and ask: Where can we find documents related to Colombia? And there they tell them: ‘Look, there is a section of this whole archive called Record Group 59, where you can find the memos and letters that ambassadors from all over the world have sent to the State Department.’

All that material becomes public, or is declassified, I think after 30 years. And when they arrive, it’s been more than 30 years since the end of World War II and they discover important information that talks about the repercussions that the war had in Colombia, which had been completely hidden. So based on that information they write the first book, which was really explosive: it’s called “Colombia Nazi.”

Donadío continues using that file for the book about the dictator and for another one he wrote about the war between Colombia and Peru. So, it’s a file that he really took advantage of and which provided an escape from the pressures he felt at El Tiempo newspaper, because he felt impotent many times. Some of the stories he wanted to publish would never be printed.

GIJN: If Alberto Donadío has been one of the fundamental figures for investigative journalism in Colombia, why is he such a shadowy figure?

Donadío started as an investigative researcher for El Tiempo columnist Daniel Samper. Photo: Courtesy of Juan Serrano

Juan Serrano: I would say there are several reasons. On the one hand, there’s the fact that, even in the investigative unit, he was always very much in Daniel Samper’s shadow. Both he and Gerardo Reyes [the Pulitzer prize winner and currently director of investigations at Univision] were actually Daniel Samper’s lieutenants and they never had that interest in appearing under the spotlight. I think that took its toll on them, on Alberto in particular. Because when he left the investigative unit, he began to write books that were no longer on current affairs, but about history. So he does not have the same media visibility as other journalists.

GIJN: How was the process of investigating an investigator?

Juan Serrano: I think when Alberto saw that I wasn’t just going [to him] for a statement to put together a story, but that I was genuinely interested in knowing who he was and telling his full story, he opened up and shared more things. I didn’t want to rely only on interviews, I also worked with documents, read his books and the investigations he published during his time at El Tiempo. I had the advantage that Alberto is very transparent and talks about the behind-the-scenes reporting in many of his books.

GIJN: When you came into contact with him, or when you met him, were you intimidated?

Juan Serrano: No. He’s a very shy person. He speaks very softly, but he was very nice to me and open; I didn’t find any barriers on his side. I think he was flattered that a young person was genuinely interested in him.

GIJN: When you set out to do the book did you have, as a goal or purpose, to rescue from oblivion this investigative journalist that your generation had never heard of or did not know?

Juan Serrano: I didn’t set out with the desire to vindicate anyone, or do them justice. I wanted to tell a good story.

GIJN: What did you learn about investigations from someone like him, who has been doing this type of journalism for 40 years?

Juan Serrano: I’m still asking myself many questions about what kind of journalism I want to do. And this book helped me realize what kind of work is really worthwhile… I’m not belittling any other kind of journalism; everyday journalism is very important to know what’s going on. But this journalism that is more demanding, that is more slow-cooked, is the one that can change things.

GIJN: Donadío thanks Bertrand Russell for what he calls his “political education,” which is at the very base of the kind of journalism he has been practicing. He takes from him the idea of fighting for certain rights, for just causes, of always speaking the truth. But that has a cost, often a very personal one. After writing this book about him, what do you think about investigative journalism?

Juan Serrano: I don’t think you can generalize, and say that this kind of journalism is completely unappreciated. But what Alberto’s case shows is that a person who has dedicated his whole life to investigating… to doing the best he can for the public interest, doesn’t get the recognition he deserves.

GIJN: Just to finish up: Was there any phrase that Donadío said to you during the interview process that has stuck in your head?

Juan Serrano: There was one occasion when I mentioned something like: “I have been studying your journalistic career,” and he cut in: “No, I don’t have a career.” The word career, me speaking in terms of a journalistic career, was offensive to him. He explained that this was his craft and not a path to consecration [as a journalistic hero]. And then he added: “My only interest has been investigation.”

Catalina Lobo-Guerrero is GIJN’s Spanish Editor and a freelance journalist. She has reported on politics, armed conflict, human rights and corruption in Latin America, mostly in Colombia and in Venezuela, where she was a correspondent for three years.

Catalina Lobo-Guerrero is GIJN’s Spanish Editor and a freelance journalist. She has reported on politics, armed conflict, human rights and corruption in Latin America, mostly in Colombia and in Venezuela, where she was a correspondent for three years.