The early spring of 2015 saw thousands of angry people on the streets of Chisinau, capital of the tiny Republic of Moldova. While calling loudly for the resignation of the Government and the Parliament, they were shouting, “We want our billion back!”.

The early spring of 2015 saw thousands of angry people on the streets of Chisinau, capital of the tiny Republic of Moldova. While calling loudly for the resignation of the Government and the Parliament, they were shouting, “We want our billion back!”.

The demonstrators believed the politicians were to blame for the theft of almost $1 billion from Moldovan banks, which had left this poor country’s financial affairs in disarray.

Investigations are ongoing. But the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project’s (OCCRP) research indicates that this $1 billion was the tip of the iceberg, in a country where many more billions of dollars in ‘black’ money appear to have flowed through a flawed banking system – with the help of corrupt politicians and organized crime as well as untrustworthy judges and law enforcement officers.

We believe that the citizens of Moldova were victims of a transnational web of corruption, benefiting politicians and criminals who used complex multi-layered company structures to conceal both their identities and their activities. Regrettably, this story is not unique.

At the OCCRP, we have identified a number of cross-border money laundering schemes in Eastern Europe, serving criminal groups as diverse as Mexican drug cartels and Vietnamese and Russian organized crime gangs.

The power of these crime groups stems primarily from their ability to operate with ease across national frontiers. They complete a detailed risk assessment at the country level and then choose the least vulnerable approach to conduct their illicit activities, whether in narcotics, refugee trafficking or the massive money laundering exercises that follow such crimes. The problem for national law enforcement is that, by definition, it cannot follow this type of crime easily or quickly across borders. Data exchanges between states and law enforcement agencies take time. Modern crime schemes are designed to have very short lives to avoid detection, lasting sometimes just months before the associated companies and bank accounts are wound up and replaced by new ones.

Yet alongside the advantages available for criminals of operating on this global scale, making it inherently harder to track them down, there are also disadvantages that the clever journalist or law enforcement official can exploit to expose them.

So how do we do this? How do we stop criminal gangs and the corrupt politicians they rely on – conducting business as usual? Firstly, I will argue, through data: more data means more transparency, provided the quality of information is there and supported by tools that allow proper analysis. Secondly, by journalists using advanced investigative techniques, including the emerging discipline of data journalism, to identify the patterns and practices inherent in corrupt activity.

Criminals can’t predict the future of open data. Transparency is the natural enemy of international organized crime gangs and corrupt officials. Opaque systems allow them to thrive. And some of them go to great lengths to disguise their wrongdoing, using financial and company structures that span the world.

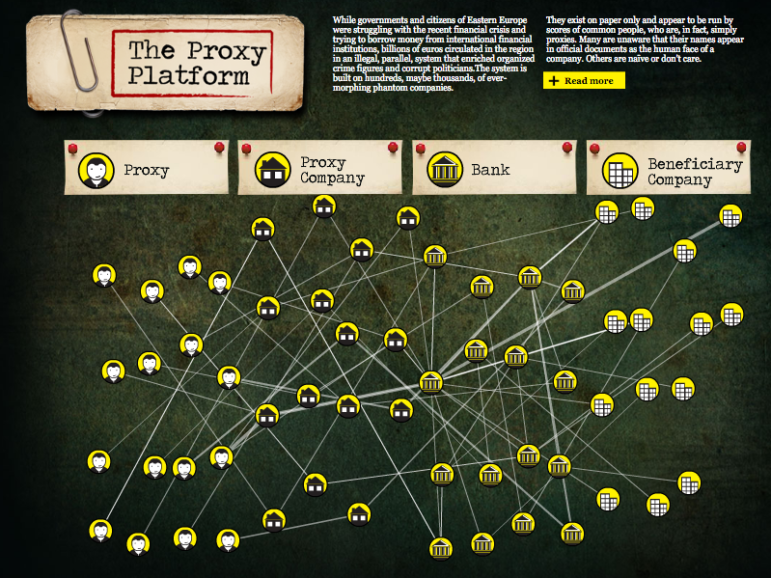

At OCCRP, we’ve found and exposed networks of companies based in New Zealand, with bank accounts in Riga, Latvia, that were transferring money to companies set up in the US state of Delaware, Cyprus or the United Kingdom. In turn, these companies owned bank accounts in yet other jurisdictions.

Tactical Technology Collective

Photo: Paul Radu. Screenshot from “Our currency is Information: Exposing the Invisible” by Tactical Technology Collective

Such criminal schemes are designed by creative and intelligent, if misguided, people. Some of them could have been the next Steve Jobs, but found crime more appealing. They often work for what we call the ‘criminal services industry’ – the lawyers, registration agents, business intelligence firms and other legitimate businesses that earn lucrative income from servicing the needs of criminal clients. But no matter how clever they are, they can’t predict the future; transparency rules change. For years, from the early 1990s, Russian, Ukrainian, Romanian and many other Eastern European mobsters and politicians were using Cyprus as a place to hide their activities behind labyrinthine corporate structures.

It reached the point where Cyprus, with a population of little more than one million, became one of the main investors in Eastern and Central Europe. Not all of these investors were criminal enterprises as many used Cyprus for tax optimization purposes. But there is hardly a country in the region – from the former Yugoslavia to Russia and beyond – where Cyprus-based companies were not involved in huge, rigged privatization scandals.

In 2004, when Cyprus joined the European Union (EU) and started opening databases, including a registry of locally based companies, things began to change. Investigative reporters began combing through millions of records and, in many instances, came across the names of beneficial owners the real owners of the company – who thought they were sheltered from public scrutiny.

Politicians and criminals were caught off guard and exposed in press articles that led to arrests and resignations. Their past misdemeanors made future involvement in business problematic. However, they started fighting back almost immediately, substituting their names in company documents with those of professional proxies – usually Cypriot lawyers who would lend their name to just about anyone who wanted to conceal their identity.

In addition to this, the Cyprus registry is relatively expensive to use and searchable only by company name. This poses a serious problem for investigators, who often embark on an enquiry with only an individual’s name, be it a member of the local parliament or a controversial business owner. As a result, Cyprus still offers only partial transparency.

Yet even in countries with a stronger record, you can hit barriers. For example, New Zealand – ranked fourth in Transparency International’s (TI) anti-corruption index – has a well-organized register of companies that is free of charge and allows for name-based searches. But, as with the UK’s Companies House database, it’s more difficult for investigative researchers to identify nominee shareholders and directors, especially in cases where they are proxies – not beneficial owners – acting for criminal groups and corrupt politicians.

And in the past few years, OCCRP investigations have revealed the involvement of an Auckland-based company (that was run by a nominee) in obscuring the ownership of companies across Eastern Europe. One such example was a Moldovan TV station. Secretive media ownership is a huge problem across the region where, in many instances, the general public has no idea who is delivering the news. Once OCCRP exposed this non-transparent structure, its ownership was just moved to British companies that were again meant to obscure the identity of the real owners of the television station.

In a global economy, this isn’t just an issue for New Zealand. In 2016, the UK Government is implementing a new central registry of company beneficial ownership to enable researchers and other interested parties to access information on individuals with an interest in more than 25% of a company’s shares or voting rights, or who otherwise control the way it is run.

It matters because well-structured and accessible databases can be goldmines for investigators and members of the public. In 2008, British computer programmer Dan O’Huiginn reshaped the Panama registry of companies and built a simple interface that, for the first time, allowed name-based searches. This was the catalyst for investigative articles that exposed corrupt dictators, criminals and their close associates all over the world. This simple technical adjustment opened their activities up to public scrutiny, costing them untold millions of dollars.

The same principle applies to other official databases. For example, court records, government spending and tenders databases vary greatly in their organization, accessibility and quality of data. In many jurisdictions, it takes investigators a lot of navigating, mining and shopping for data to find the evidence they are looking for. The opening up of company information and databases has to be accompanied by effective policies that ensure their accessibility, integrity, security and usefulness. Civic hacker collectives, journalists and civil society groups should be consulted to help determine the most useful access to data that also mitigates any privacy concerns. Governments requiring offshore companies operating in a country to identify their true beneficial ownership would also greatly reduce the space in which criminals can work and increase the costs they incur.

Fighting from Within Borders

Grand Theft Moldova, an OCCRP investigation.

Law enforcement must also jump on board the open data train and take advantage of advances in technology in order to keep pace with the criminals. Just like journalists, police officers and intelligence analysts need to master cross-border, multi-language, open-source intelligence to fight sophisticated serious crime. While it is true that data obtained in informal ways cannot always be used to build strong court cases, it can greatly shorten the time required for the investigative process.

Obtaining documents sequentially through official channels from other countries can take months or even years. Say, for example, that the police in the UK need information on a company based in Russia. They have to file requests and wait, sometimes for a year, only to find out that the Russian company is owned by a Cyprus limited firm. It might take another year to identify the next owner in a nested structure. Finally, the trail might end with bearer shares: where the owner of the stocks is not registered or is a proxy who doesn’t know the real owner.

Compare this with the adaptability of organized crime, which – albeit operating under no formal constraint – broke free from the nation-state mindset long ago. In the international space governed by weak international protocols and bilateral agreements, organized crime at present has no natural enemy. While criminals recognize no borders and are not bound by strict local rules, national and legal boundaries, a lack of resources continues to hamper law enforcement. Geopolitics can also deter cross-border collaborative initiatives between nation-states, which may find themselves at odds with their neighbors or dealing with governments that are themselves riddled with corruption.

There are, to be sure, examples of criminal networks being disbanded in a number of countries as a result of co- operation between law enforcement agencies. This did not necessarily prevent the mobsters from re-forming elsewhere outside those jurisdictions. Nevertheless, increased access to open data could help to boost cross-border co-operation and journalists can play an increasingly important role in it.

It Takes a Network to Fight a Network

Investigative reporting is – and can be even more – the natural enemy of criminal networks and, when practiced collaboratively, it acts as an effective watchdog. It can change the status quo in innovative ways that are not immediately obvious.

Journalists and the public alike expect prosecutors to act after each journalistic exposé, with the desired result being arrests, convictions, repatriation of lost assets and other positive outcomes. Owing to limited human resources and a lack of skills, interest or even competence, this expectation is not always realized. However, regardless of law enforcement action or inaction, public exposure can adversely affect, and even stop, criminal businesses operating in other jurisdictions. Such exposure can also influence long-term changes in public attitudes, which can lead, in turn, to protests against, and even election defeats for, discredited parties or politicians.

With the stakes so high, it is essential that the journalism itself is rigorous, credible and transparent. Investigative articles must be linked to evidence, well- designed databases and ‘how we did it’ guidance, so that readers can recreate the investigative process if they want to. Governments, banks and financial institutions in general rely on open source information when deciding whether to give loans, enter business deals or accept money transactions. Effective data journalism can also help expose financial irregularity or illegality and prevent crime figures or oligarchs securing loans, opening accounts or making other transactions.

Using advanced investigative techniques, journalism can degrade international organized crime and corrupt networks even before they are firmly established within a jurisdiction. Corrupt politicians, officials and criminals view the proceeds of their illicit schemes as commodities to be repeatedly imported and exported and are always looking for new territories in which to generate profit.

When journalists work collaboratively across frontiers, sharing data, this practice can be identified and compromised. It takes a network to monitor a network.

International reporting groups such as the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists, Arab Reporters for Investigative Journalism (ARIJ), OCCRP and others already co-operate on individual stories or sporadically share datasets. However, such is the scale of the problem and the ubiquity of organized crime that these efforts can seem to be only scratching the surface.

What journalists can do is share with colleagues in other countries details of the patterns of crime they have already detected in their own. This would enable wider cross-border investigations to determine whether the same criminal groups are setting up shop in other jurisdictions.

For example, a criminal group sets up Limited Liability Partnerships (LLPs) that are all owned by a set of companies with their headquarters on a particular street in Belize City, Belize. Replications of this simple pattern can be searched for in the company registries of other countries or in related datasets, potentially revealing the group’s activities in those territories too.

In future, with the proper resources, this kind of pattern recognition could be facilitated and automated through the development of specific algorithms. Crime groups will inevitably react by altering their activities to avoid detection. But, crucially, this will hamper their operations and cost them more in money and time.

Automated searches of ever-larger, global, transparent datasets can feed real-time alerts to journalists all over the world. The result could be that the public has earlier and reliable information about who the real corrupt beneficiaries of crimes are, such as the $1 billion bank theft that left the Republic of Moldova with an uncertain future.

To conclude, a key component to fighting future crime is increased cross-border co-operation between journalists and programmers, who need to employ and create new advanced investigative techniques on top of massive amounts of data. At the same time, activists and governments need to push for more transparency, quality and common standards in open data.

This story originally appeared on the website of the UK Government as part of the policy paper “Against Corruption: a collection of essays” and is reprinted with permission.

Paul Radu is the Executive Director of the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project, which investigates transnational crime and corruption in Eastern Europe. He is also a board member of the Global Investigative Journalism Network and has received many international awards for his journalism.

Paul Radu is the Executive Director of the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project, which investigates transnational crime and corruption in Eastern Europe. He is also a board member of the Global Investigative Journalism Network and has received many international awards for his journalism.