Sudanese girls seen in Darfur, Sudan, 2005. The 12-year-old girl wearing the striped scarf (front), tells how she was separated from her two friends and raped by soldiers from the Sudanese government. Image: Courtesy of Ron Haviv, VII

Editor’s Note: This is a chapter excerpt from GIJN’s Reporter’s Guide to Investigating War Crimes. The full guide will be released on our website next week and an ebook version of the guide will be published later this month during the Global Investigative Journalism Conference.

As an investigative journalist interviewing witnesses to potential war crimes, you will encounter one constant: the work involves trauma. Reporters will routinely face situations involving death, injury, sexual violence, or the threat of those.

Some of a reporters’ contacts will be more peripheral witnesses to violence, some survivors of direct military attacks, and yet others may have been subject to intense interpersonal cruelty, expressed in torture, sexual violence, or detention in inhumane conditions. The scale of impact is likely to be greatest among those closest to events.

Everyone you meet in a conflict zone, however, will have had to adjust to living with pervasive threat, disruption, and immense uncertainty. This chapter explores what effective and sensitive interviewing in this context looks like.

Starting Points

Journalists often worry that the act of talking about painful experiences can re-traumatize an interviewee. Many trauma experts, however, believe that expression may be more confusing than helpful in clarifying where the risks lie.

When people talk about painful events in the past, distress — manifested in concentration lapses, heightened emotionality, numbness, and other difficulties — is likely. If journalists are working responsibly, that distress will be a natural by-product of those past (or continuing) events — not fresh injury.

During conflict-related violence, perpetrators treat their victims as objects, a means to an end, rather than as individuals deserving dignity and consideration. The key is to avoid behaving in any way which echoes the original abuse and deepens a source’s feelings of powerlessness.

Some examples of behaviors to avoid: over-interviewing a source by a procession of journalists, forcing someone to discuss details they would rather not, dismissing or ignoring a source’s emotional state, or displaying a lack of transparency about how someone’s contribution will be used.

The suggestions below delve deeper into how you can build safety into these conversations by extending choice and control to interviewees. Working in this way will also increase your chances of returning with an account that is accurate and insightful.

Don’t forget, survivors and witnesses often do very much value the opportunity to have their story heard.

A family poses with a portrait of their daughter, 16, who was killed while serving with the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam, LTTE, in Sri Lanka, 2007. Image: Courtesy of Ron Haviv, VII

Begin With a Clearly Established Plan

The more internal clarity you have, especially on where your limits as a journalist lie, the better positioned for an interview you will be. The following silent mantra may sound obvious, but it is surprisingly easy to lose sight of when talking to someone in distress. Before setting out, it may help to remind yourself: I can facilitate someone’s attempts to relate the most relevant information they are able to share — and do that well — but I can’t take away the pain or mend the situation.

Confronted with horror, journalists can often feel compelled to make promises beyond their power to keep, like offers of future emotional support, aid for the community, or the certainty of justice. This can lead to interviewees feeling betrayed, and interviewers feeling morally compromised.

Some other interview planning best practices are as follows.

Allow for enough time. People need more conversational space to relate emotionally challenging experiences; they should not be rushed. If security dictates short time windows, explain that in advance and focus the conversation on surface-level facts.

Be prepared for their distress (and yours). Being ready for the possibility that the conversation may be upsetting, both for your interviewee and for you, can make things easier to manage. Taking a few moments to reflect on this in advance is analogous to packing a raincoat before heading out into bad weather. The rain might get through in places but that is OK.

Research the context. Different cultures may have different sensibilities around eye contact, physical proximity, gender, etc. If you are not local, find out more. Those working with translators will find this discussion a good primer on bridging cultural divides when establishing consent from your subjects. And do, of course, brief yourself on the historical and cultural background, including recent political developments.

See each story as unique. Doing many, near identical interviews can lull someone into believing that they already know what the next person is going to say. This is an easy — but potentially toxic — trap that can undermine productive interactions.

Look for the person beyond the atrocity. Descriptions of horrifying events have the power to suck us in, simultaneously obscuring sight of the more positive dimensions of people’s lives. Be careful not to reduce someone to the worst thing that happened to them. Remember people are also likely to read what you write about them. This resource discusses your responsibilities when writing up atrocities and covering graphic details.

Try not to blur your experiences with their experiences. Having similar personal backgrounds or trauma can generate some valuable insights as an interviewer, but watch out for unhelpful forms of projection. The focus of the conversation should primarily be on them — so share personal detail appropriately and sparingly.

Understand trauma’s role in memory. Memory encoding — the way the brain creates memories — works differently during intense, life-threatening events. Afterwards, people may inadvertently reorder events out of sequence, confuse who did exactly what, or have whole gaps in what they can recall. Inconsistencies are not in themselves evidence of deception. You will need to use multiple sources to construct timelines and fact-check sensitively in ways that don’t imply that you disbelieve them. Keep in mind it may be unfair to expect some sources to clarify certain details.

Consider how to involve sources in visual choices about their lives. Survivors often find it upsetting when journalists take images of themselves or their relatives off social media without consulting them first. It feels invasive and the images may not correspond to how they would like their loved ones to be remembered. Taking and using pictures and video is a complex area that benefits from planning in advance and prioritizing consent whenever possible.

The more one knows about trauma, the more insights a reporter will have into innovative and impactful ways of covering these stories. Check out the Dart Center website for examples of how other journalists have approached these challenges.

Include a Plan for Your Interviewee’s Physical Safety

In crisis zones, you are responsible for assessing the risk of your interviewees’ physical safety as well as your own. Ask yourself some key questions: Could an interview expose your source to further danger? Is there potential for backlash from the community? Does anonymity need to be protected? Who shouldn’t be in the room? How can we talk without being overheard? This guide on covering conflict-related sexual violence — specifically chapters two and eight — offers detailed checklists for you and your editors to discuss.

Take Additional Care With Consent

Your interviewee needs to have a clear understanding of what they are getting into by talking with a reporter — it may not be obvious to them. So do take extra time to explain what the process involves and how their contribution will be used, including how you are planning to record and edit images and sound.

Finding out that the final product also includes the voices of alleged perpetrators can come as a nasty shock to victims who are not expecting that.

Asking what your interviewee expects to get out of talking to you can help bring hidden assumptions to the surface. For example, you might need to state clearly that you can’t guarantee that speaking to you will bring the perpetrator to justice.

Your sources also need to know that, thanks to the internet (or broadcast piracy), anything published could be accessible to anyone, including people in their community. You may want to show them examples of similar work and warn them that trolling may be a possibility.

If there are any aspects of granting an interview that might complicate their ability to seek future legal redress, explain that too. The principal dangers revolve around breaking the chain of custody, asking leading questions that could bias responses, and a source volunteering multiple accounts that contain apparent inconsistencies.

Think of the consent conversation as an audition. If a contributor or source is likely to drop out, it is good to know early, especially on films and projects which can involve a major time commitment.

Cede Control Where You Can

Typically, trauma reduces people’s sense of control. In response, look for ways of increasing your interviewee’s agency. Even small gestures can make a real difference.

- Involve people in the decision about where the interview takes place and whether they would like someone they know to be there.

- Acknowledge that speaking might be difficult and explain that there is no need to discuss anything they would rather not. Ask ahead of time if there are any topics that are off limits.

- During the conversation itself, recheck permissions with the occasional: “Is it OK to ask about…?”

- Try not to fish for feelings. The classic “How did you feel?” prompt can dig into people’s emotions in a way that is unbalancing.

- Be aware that why questions and snappy requests for specific details are used by interrogators. Framing a question like: “Why did you do that?” can imply that someone made an error and amplify blame.

- If you meet resistance, don’t push through defenses. Find another route to the information you need.

Be mindful that the standard interviewing strategies reporters employ for powerful figures, such as business people and politicians, are often about wresting control away from your sources and pressuring them to reveal more than they are comfortable saying. You still need certain information, but these reflexes are best put aside when dealing with victims or eyewitnesses to atrocities.

Facilitate the Best Conversation

Having a plan is still important when interviewing survivors or victims. These conversations benefit from being well-structured with clear objectives.

Listen actively. Nothing builds a sense of being in good hands as effectively as the feeling of being listened to. When a journalist is fully present, people are generally forgiving of the need to take notes or check sound.

Try structuring in thirds. Dividing the conversation, so that the most challenging events are sandwiched in the middle, can lessen the danger that your interviewee leaves the encounter with the worst details still at the top of their mind.

Start on topics that are likely to be relatively safe or neutral. This also builds rapport. Then move on to the key events you need to explore. Finally, try to bring the conversation back onto safer ground. There is no exact science to this. If the conflict is over, you could ask about life since the war. Finding less traumatic ground to finish on is harder if fighting is ongoing or recent. You could always ask what someone is planning to do after the interview, later in the day or that week.

Favor simple, open questions. Setting out with a broad topic, e.g. ‘What can you tell me about the day the soldiers arrived?’ can be easier to answer than more specific queries. A broad question gives people choice over what they are most comfortable discussing. Once some mapping has taken place, reporters can circle back with more narrow, detailed questions.

As discussed above, traumatic memory is often fragmented and less linear. People may find the question ‘What happened next?’ surprisingly hard to answer. Instead, ‘What else can you tell me about X?’ may prompt a more useful response.

Keep an eye on the clock. Talking about trauma can be exhausting, and people may forget their own needs out of a desire to be helpful. At the outset, remind interviewees that they can have a break at any time, and during the conversation, watch for signs of unusual fatigue. You may want to offer the option of following up on another day.

Wrap up well. Have a contact plan in mind for afterwards and always follow up on any promises you make. Consider reading out the quotes you use so your source knows what to expect on publication.

As discussed above, you are not a clinician and so offering detailed, unsolicited advice is usually not a good idea. But where someone expresses an interest in seeking additional support, you can guide them to relevant local organizations and resources.

Be Accepting

Do acknowledge people’s distress. Depending on what is appropriate to the situation, you might say variations on the following: ‘I am so sorry that happened to you,’ or ‘That must have been unbelievably hard.’

Big emotions like shame, guilt, anger, fear, and helplessness are the unseen currents that drive the weather system of war. People often blame themselves for things over which they had no control. And in cases of torture and sexual violence, enduring stigma may well linger in some communities.

If somebody shares details that horrify you, avoid betraying your reaction by making an uncomfortable face or anything else that might trigger shameful feelings from your source.

Crying is not at all unusual in these interviews. In fact, it often happens when people start to feel safe in the conversation. Again, be open. You might give someone a moment to compose themselves, then ask if they want a short break or prefer to carry on.

Sometimes, people may re-experience elements of the actual pain that they had during the attack itself. An interviewee might start to dissociate (space out) or become hyper-alert, as if they were back in that danger. You need to exercise real care in these moments, as this could be a sign that someone is starting to lose control of their emotions.

An elderly Bosnian woman sits and smokes a cigarette by the side of a road in Bihac Pocket, Bosnia, 1995. She was expelled from her hometown and arrived in a village that had just been cleansed of Serbs, where she was forced to flee again a few days later when Serb troops retook the village. All forces attempted to cleanse areas into ethnically pure groups during the war in Bosnia. Image: Courtesy of Ron Haviv, VII

If someone is stumbling over a memory, don’t dig into that gap, as it may disorientate someone further and undermine their efforts to look after themselves. Similarly, avoid direct touch: it can feel invasive.

Instead, model calm and change the conversation in a way that helps the person focus back on the present — that is, being in the room with you — rather than back in the experience of what happened. There is a helpful guide that has more detailed advice on this.

If interviewees get angry, express opinions that you find hard to listen to (or morally repellent), or complain about personal losses that appear trivial compared to other people you have recently interviewed, let people have their feelings. This is probably not the time to challenge them.

There is also a safety dimension here: if someone becomes threatening, find a pathway to de-escalation and an early route out of the conversation.

Other Resources

The Dart Center Style Guide for Trauma-Informed Journalism

GIJN’s Guide on Interviewing Witnesses to Violence

Reflections from an Editor on Working with Torture Survivors

Gavin Rees is Senior Advisor for Training and Innovation at the Dart Center for Journalism and Trauma, an organization dedicated to promoting ethical approaches to the coverage of trauma and violence. With a previous background in broadcast journalism and documentary filmmaking, Gavin has been working since 2008 as a trainer and consultant to news organizations, film production companies, and media support organizations in more than 25 countries. He was a leading producer on the BBC film “Hiroshima,” which won an International Emmy in 2006. He is a board member of the UK Psychological Trauma Society, and was on the board of the European Society for Traumatic Stress Studies for more than ten years.

Gavin Rees is Senior Advisor for Training and Innovation at the Dart Center for Journalism and Trauma, an organization dedicated to promoting ethical approaches to the coverage of trauma and violence. With a previous background in broadcast journalism and documentary filmmaking, Gavin has been working since 2008 as a trainer and consultant to news organizations, film production companies, and media support organizations in more than 25 countries. He was a leading producer on the BBC film “Hiroshima,” which won an International Emmy in 2006. He is a board member of the UK Psychological Trauma Society, and was on the board of the European Society for Traumatic Stress Studies for more than ten years.

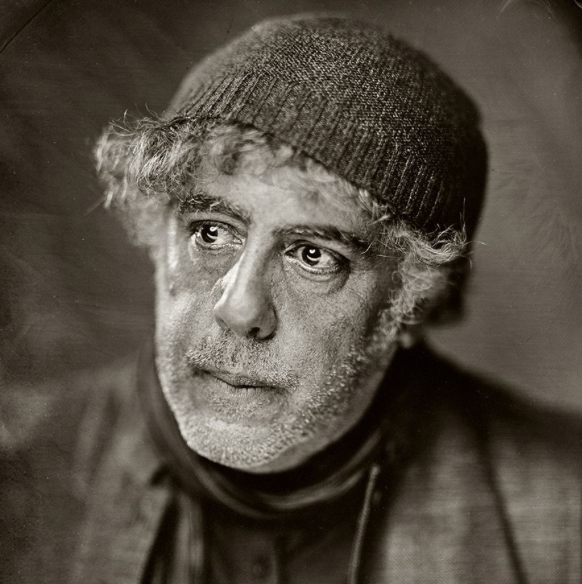

Ron Haviv is a director and co-founder of The VII Foundation and co-founder of VII Photo Agency. In the last three decades, Haviv has covered more than twenty-five conflicts and worked in over one hundred countries. His work, which has won numerous awards, is featured in museums and galleries worldwide.

Ron Haviv is a director and co-founder of The VII Foundation and co-founder of VII Photo Agency. In the last three decades, Haviv has covered more than twenty-five conflicts and worked in over one hundred countries. His work, which has won numerous awards, is featured in museums and galleries worldwide.