Members of Željko Ražnatović’s paramilitary group the Serbian Volunteer Guard, also known as the Tigers, gathered around executed, unarmed Muslim civilians during the first battle of the Bosnian war. This image was used as evidence in numerous procedures to indict and convict people of war crimes. Image: Courtesy of Ron Haviv, VII

Editor’s Note: This is a chapter excerpt from GIJN’s Reporter’s Guide to Investigating War Crimes. The full guide will be released on our website next week and an ebook version of the guide will be published later this month during the Global Investigative Journalism Conference.

One of the most critical things that journalists seeking accountability for violations committed by police, military, or other security forces can expose is the chain of command, or the process of how orders and policies are implemented. If the chain of command for the perpetrators is established, then senior officers and even political leaders in that chain of command can be held accountable for the actions of their subordinates through the international law concept of command responsibility (see this guide’s chapter on What Is Legal in War for more detail). Documenting the chain of command can be incredibly challenging, due to state secrecy, a general lack of information, or reluctance of those with knowledge of the chain to be sources for journalists. This chapter will lay out different approaches a journalist can take, primarily focusing on open source techniques that can be supplemented with additional reporting.

A chain of command is a hierarchy of military or police leaders of ever-larger units that continues up to a final commander-in-chief, which is often a country’s defense minister, president, or head of state. At the bottom level, typically, are small tactical units, which would most likely be the ones directly committing any violations or potential war crimes. Reporting on this chain of command by identifying specific units and commanders, as opposed to more generic reporting on “police” or “soldiers,” can provide more key details about a suspected atrocity, but it can also increase the risks for both reporters, who could be targeted for “naming names,” and senior commanders, who could be subject to criminal charges for the actions of their subordinates.

For senior commanders to be held accountable, a reporter has to connect the actions of individual soldiers, police, or security forces to them via the chain of command. However, just because someone is the minister of defense or president doesn’t necessarily mean they are responsible for every act or operation, nor that the path from low-level personnel up to them is clear (not every country’s defense minister is in the military chain of command, for example). Prosecutors and courts need to know the specific role of commanders at every level for successful prosecutions of misconduct or violations of international humanitarian law. Accurately reporting and identifying the individuals in the chain of command aids these efforts.

Reporting on the chain of command is a valuable endeavor even in situations where criminal accountability is not possible in the near term. Individuals who may be able to avoid criminal prosecution can still face consequences under a variety of national, multilateral, and international sanctions regimes, depending on their involvement in the commission of human rights violations. Even when commanders cannot be identified, naming specific units as perpetrators empowers advocates to question their own governments about any training or support that may have gone to those specific units. For example, advocates could use reports on atrocities or possible war crimes committed by specific units as leverage to pressure the United States to follow its own laws restricting training and support to units that have been linked to human rights violations. All of this relies upon identifying and reporting on specific units and leaders in the chain of command.

The rest of this chapter is structured to provide general background on the structures of police and military forces with tips for investigating them, general tools that can be used in any type of reporting, and, finally, case studies linking violations to the chains of command of different security forces around the world.

Chain of Command: Definitions

Overview

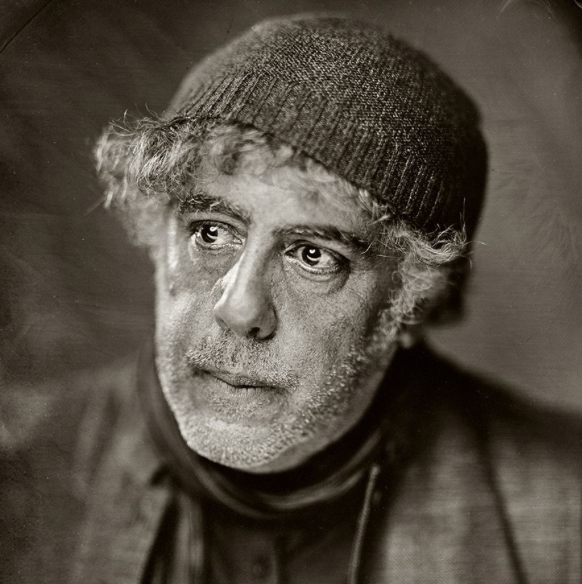

Serbian nationalist Željko Ražnatović (center) poses in front of the paramilitary force, the Serbian Volunteer Guard, also known as the Tigers. In 1997, a UN tribunal indicted Ražnatović for crimes against humanity for his role as leader of the Tigers while they conducted mass slaughter of Croat and Bosnian Muslim civilians in the early 1990s. Image: Courtesy of Ron Haviv, VII

The police, military, and other security forces of a country are hierarchical organizations where the chain of command resembles an inverted family tree with a single “head” at the top, usually the president or a minister. Below that sits a single or parallel senior commanders overseeing subordinate units that, in turn, command multiple smaller units. Thus, most security forces are ultimately controlled by a small number of civilian leaders, with the rest being members of the security force itself. Officers usually hold command positions within the security forces and exert control over each other based on their rank. The more senior the rank of the officer, the higher they will be on the chain of command, typically.

Broadly, there are two types of groupings — 1) territorial units that control operations in a particular area and remain within that area, and 2) mobile forces that are often deployed around a country to respond to events. How these units relate to one another can vary, either the mobile units can fall under the command of the territorial units when they are operating in their territory, or the mobile units can operate in parallel to the territorial command with both units reporting up the chain to higher level formations.

Generally the people at the top of the chain of command give orders and receive reports of outcomes of their orders while the people and units at the bottom carry out these orders. So, when reporting on a particular incident, it’s important to recognize that top level commanders will likely not be physically present during an operation. Instead, they rely on subordinates to communicate orders down the chain and carry information back up to them. The commander of a small police station might participate in an operation with the officers under his command, but that person’s superior may sit at a desk in the provincial capital and that person’s commander may be located far away in the nation’s capital. But even though these remote commanders are not present, they could still be held responsible for the actions of their subordinates (again, see What Is Legal in War for more information).

Similarly, security forces generally have units whose role is to conduct operations out in the world (such as arresting people) and other units which provide support, whether it’s logistics or managing personnel files. Understanding these roles and responsibilities for different units is important, though often the names of these units will provide a clue. The support units are usually part of a higher level unit as security forces become more “operational” and undertake more tactical missions further down the chain of command.

Tips

- Look at the constitution and laws of the country. These will establish who or what is at the top of the chain and give a framework that can help guide the rest of the investigation. Generally, these establish top-level control, such as the president is the commander-in-chief of the military who delegates day-to-day control to the defense minister or army chief. The Library of Congress, a US government body, can be a useful resource on the relevant laws or constitution, if it is not readily available elsewhere.

- Read experts/scholars. One of the best sources for finding books and other scholarly literature is WorldCat.org. Searching for “security forces” or related terms could provide details about basic formations of the military of a country. However, it may not cover aspects of the chain of command established by the constitution and laws of the country, so it is best to research both resources when possible. Expert analysis can also be found at the Geneva Centre for Security Sector Governance, International Crisis Group, and other organizations concerned with security sector governance.

- Listen to what the forces say about themselves. Security forces often publish information that, when combined with the constitution, laws and experts analysis, will give a clearer picture of the chain of command. For example, when the police publish their own report about an arrest that identifies the unit responsible, they could establish that unit is responsible for that geographic area. Militaries regularly have public-facing events with speeches given by commanders, donations made by prominent citizens, and other events where specific units and commanders are regularly identified.

Police Forces

The police generally reflect the political structure of the country, so unitary states often have a single unified national police force and federal states usually have a mix of national (federal) forces and sub-national forces. The command structure of the police will almost always follow the administrative boundaries of the country. The chain of command will have units responsible for the governorate, province, or region, with subordinate units responsible for the smaller administrative areas (district, sub-governorate, city, etc.), and individual police stations or posts responsible for even smaller areas. For example, the Philippines is administratively divided into regions, provinces, cities, and then barangays, which the Philippine National Police mirrors in its command structure. See the Tools section below for more information on how to find and navigate complicated administrative boundary hierarchies.

Occasionally, the police force of a country may be divided by function, into “judicial” police that investigate crimes after they have been reported and “preventative” police that conduct operations. In these cases, both judicial and preventative police are still often structured to follow the administrative divisions of the country. So a province will have a preventative police unit commanding other similar police units in the province, and the judicial police will have the same structure.

Militaries/Armed Forces

The president, head of state, or prime minister is almost always the commander-in-chief of the military for any country. From there, the chain of command may fall to the minister of defense, and then to an overall day-to-day commander of the military. Sometimes, however, the defense or interior minister is not in the chain of command, for example, the Ministry of Defence of Nigeria only provides administrative support — rather than operational control — to the military.

Militaries generally are divided into three major branches: army (responsible for ground operations), navy (responsible for ships and operations along the coastline or the ocean), and air force (responsible for aircraft and air operations). These branches usually fall under an overall commander of the armed forces with each branch having its own commander and separate chain of command. Gendarmeries (where they exist) are usually structured similarly to the police, but may fall under the command of the military. The Council on Foreign Relations provides a useful overview of the standard types of units and nomenclature that make up most military forces. For example, many countries’ militaries are organized with army divisions that command multiple brigades, with each brigade commanding multiple battalions.

Tips

- Look out for missing “middle managers.” There is a natural bias to focus on commanders closest to events and high level commanders who are often in the spotlight. However, sometimes sources can be accurate but potentially misleading about the chain of command, which could negatively impact an investigation. For the purposes of illustrating this point, we’ll invent a 10th Battalion, which is part of the 35th Brigade, which is in turn commanded by the 82nd Division. Reports might say “the 10th Battalion, which is under the 82nd Division, committed the violations.” While this is accurate, it also omits the intermediary brigade, and potentially worse, could confuse someone into thinking that the battalion reports directly to the division. Missing this aspect could overlook the potential role in any incident played by the brigade commander, who could also be accountable for actions of the battalion.

- Double-check the numbers and nomenclature. The single most common source of bad information about security forces is the result of typos. The difference between the 11th Battalion and the 111th Battalion is a single keystroke. If you ever encounter two units with very similar numerals operating in the same area (or under the same superior unit), that is cause for careful cross-referencing to confirm that those two units do indeed exist. Simple typos like in the example above have mistakenly created non-existent units around the world, ballooning the estimated size of security forces in certain countries by 25 – 100%.

- Keep track of acronyms. Security forces use a myriad of acronyms, abbreviations, and other jargon that can make it difficult to understand. A simple Google Sheet is a free way to track these acronyms and abbreviations as they are discovered and decoded. Usefully, discovering the meaning of an abbreviation for one unit or type of group can aid an investigation into another similar unit.

Joint Task Forces and Other Ad-Hoc Groups

Governments will often establish some sort of joint force to conduct operations in an area in response to a crisis. This joint task force will often combine different military services — like the army and navy units — or take units sent from other parts of the country to operate in unison in the crisis area. These joint task forces often have their own chain of command that can be outside the regular hierarchy, with senior commanders reporting directly to ministers or even the president.

It’s important to realize when investigating a joint task force that they are rarely permanent. So, it’s best to focus on the individual units when reporting, as they will still be active after the joint task force is dissolved. For example, the Saudi-Emirati-led airstrike campaign in Yemen was made up of at least 19 squadrons that will continue to exist long after the coalition itself ends. Another example, the Nigerian Army has organized several different task forces around the country for different missions, which have been disbanded and replaced with other joint task forces. But all of these have been created using soldiers from permanent-established battalions and brigades within the Nigerian military.

An elderly Afghan man is questioned by two Afghan National Army soldiers during a 2011 mission conducted by a Polish Army joint task force in Ghazni, Afghanistan. Image: Shutterstock

De Facto Versus Formal Chains of Command

While laws and policies establish the legal and formal chains of command of state security forces, there can also be informal/de facto chains of command that supersede or exist alongside these formal structures. A good approach is to first map out the formal structure and then investigate whether there is any alternate chain of command, as these will often touch one or more parts of the formal structure. For example, an army battalion is technically controlled only by its parent brigade, but the battalion commander might also take orders from a powerful local politician because of personal or financial ties between them. As a result, the battalion has two functional chains of command, one formal and one informal. If the battalion committed violations while under the de facto control of the local politician, that public figure — and not the brigade commander — could be held accountable.

De facto chains of command outside of the formal structure can be established for a wide variety of reasons, often based on loyalties or shared identities outside of the rules establishing the formal chain of command. Previous service in the same area can also establish important ties among different actors in the security forces. Additionally, most security forces have formal academic programs for officers and these personal relationships formed in military or other academies can form important informal links between officers.

Tips

- Investigate the peer units. Use the chain of command as a guide to what units and commanders should be investigated in relation to any incident. There is a natural push to focus on the particular unit(s) most closely located to an incident, but this may obscure other relevant actors. So if the army is accused of committing violations in a specific town, look at all of the units under the command of the unit responsible for the district/province/governorate where that town is located. This may help frame any reporting on de facto relationships by having a comparable unit that follows the formal chain of command.

- Know the ranks. Information on the rank structure can often be found in the laws of the country and are important in establishing the hierarchical relationship between commanders. A useful reference point are NATO military ranks – which are often mirrored by other countries’ armed forces.

- Look at unusual sources. Phone books, social services for service members, obituaries, and other general sources could be tremendous assets providing a wealth of useful information about links between service members and their units.

Tools for Journalists

- Check WhoWasInCommand.com. The Security Force Monitor runs WhoWasInCommand.com, a comprehensive platform with data on police, military, and other security forces. The data is freely available to use and individually sourced for each datapoint. It may be that the information needed for an investigation has already been collected and published on the platform. The Monitor’s entire methodology and approach is available online as well as a sample spreadsheet to organize information on state security forces.

- Finding deleted/removed information. The Internet Archive’s Wayback Machine can be a powerful tool for preserving many (but not all) types of digital information, in particular for government or other official websites where information has been taken down. Governments will regularly delete information from their websites, often not in an attempt to hide information but simply as a process of “updating” old content. Bellingcat has a useful guide for thinking about digital preservation of materials in addition to the Wayback Machine.

- Understand administrative boundaries. OpenStreetMap and its Nominatim tool are the two best resources to find, discover, and analyze geographic information, in particular administrative boundaries of a country. Make sure to understand the hierarchy of administrative divisions, as this will be reflected in the chain of command of the security forces. OpenStreetMap’s data can be used to create maps as well for any final publication.

- Visualizing a command tree. A fantastic free tool to build a command tree is yEd, which offers a multitude of ways to map out chains of command.

Case Studies

Identifying US Support of the Saudi-led Airstrikes in Yemen

This joint investigation conducted by The Washington Post and the Security Force Monitor at Columbia Law School’s Human Rights Institute (SFM) used information drawn from books, media reports, and videos to establish the specific units participating in the Saudi-Emirati led air coalition in Yemen. This was combined with a careful combing of the US Department of Defense daily contract announcements to connect specific contracts with support for the coalition airstrike campaign.

The Washington Post collaborated on an exposé on Saudi-led airstrikes in Yemen. Image: Screenshot, The Washington Post

Confronting Mexican Army Misconduct

By conducting extensive interviews with soldiers, journalists worked to understand the thousands of confrontations between the Mexican Army and civilians or non-state actors across an eight-year period that often resulted in deaths of civilians. Using the data on these incidents put out by the army itself, where civilians were described as the aggressors, numerous journalists collaborated on the project Cadena de Mando (Chain of Command, in Spanish) in Mexico, which dug deeper into the dynamics that led to 19 people being killed for every death of a soldier. The interviews, which often focused on specific incidents, were combined with information drawn from laws, media reports, and army press releases to connect the experience of individual soldiers to the larger chain of command.

How an Elite Nigerian Unit Killed Dozens of Protesters

Videos allegedly showing the killings of protestors by the Nigerian Army in Abuja prompted The New York Times’ visual investigations team to identify the specific units responsible. Reporters compared the army’s version of events to what could be reconstructed via social media from multiple different angles before, during, and after the army opened fire, zeroing in on specific parts of videos showed the insignia of the army units that shot at the protestors. Using a mix of open source information and traditional reporting, The Times journalists were able to identify the specific battalion seen in the video and establish the chain of command from that battalion all the way up to the president.

The Uncounted Dead of Duterte’s Drug War in the Philippines

Gathering reports from the police, media, and civil society, journalists built a comprehensive dataset of drug-related killings by the Philippine National Police in the first 18 months of that country’s “drug war.” Using information on the areas of operation of specific police stations and their chains of command, a team from The Atlantic was able to conduct on-the-ground reporting of the impact of the killings. Using their data, the Human Rights Data Analysis Group was able to conduct a statistical analysis that showed the actual death toll could be more than three times higher than the official count. The story was cited in a request by the Prosecutor of the International Criminal Court to open an investigation into the situation in the Philippines.

Tony Wilson is the founder and director of the Security Force Monitor at the Columbia Law Human Rights Institute. He has led the research on security forces of over 20 countries and contributed to investigations published in The Atlantic, The New Humanitarian, The New York Times, and The Washington Post.

Tony Wilson is the founder and director of the Security Force Monitor at the Columbia Law Human Rights Institute. He has led the research on security forces of over 20 countries and contributed to investigations published in The Atlantic, The New Humanitarian, The New York Times, and The Washington Post.

Ron Haviv is a director and co-founder of The VII Foundation and co-founder of VII Photo Agency. In the last three decades, Haviv has covered more than twenty-five conflicts and worked in over one hundred countries. His work, which has won numerous awards, is featured in museums and galleries worldwide.

Ron Haviv is a director and co-founder of The VII Foundation and co-founder of VII Photo Agency. In the last three decades, Haviv has covered more than twenty-five conflicts and worked in over one hundred countries. His work, which has won numerous awards, is featured in museums and galleries worldwide.