Two Yazidi teenage girls reunited in a camp for displaced people near the city of Zakho in northern Iraq. Both were captured by ISIS extremists, repeatedly raped, and forced to convert to Islam before ultimately escaping. Khanke, Iraq, 2015. Image: Courtesy of Ali Arkady, VII

Editor’s Note: This is a chapter excerpt from GIJN’s Reporter’s Guide to Investigating War Crimes. The guide will be released in full this September at the Global Investigative Journalism Conference. The end of this post also features a special focus interview by Olivier Holmey with Congolese investigative journalist Ruth Omar, whose coverage, including this BBC documentary, has extensively examined the epidemic of sexual violence during the years of violent unrest and civil war in the Democratic Republic of Congo.

There has always been sexual violence in war. From the Ancient Greeks, Romans, and Persians to the Spanish Civil War and World War II; from Guatemala’s Civil War to the onslaught by Islamic State (ISIS) across Iraq and Syria, and most recently Russian fighters in Ukraine, there is hardly a conflict where it hasn’t happened.

Sometimes this is random and opportunistic in the general chaos of war. But in recent years we have increasingly seen it used as a weapon of war — where forces are encouraged or ordered by commanders to rape or abduct women and girls for religious, ethnic, or political reasons. Sexual violence not only targets women and girls, it’s also used against men and boys — but the latter is rarely reported because it’s even more taboo.

Sexual violence is endemic in conflict. It has been written about in classical literature, and portrayed in famous works of art such as the Peter Paul Rubens’ painting The Rape of the Sabine Women. Yet until recently, it was hardly reported in the media, and is rarely prosecuted. Rape is the most neglected of war crimes — accountability for it the exception not the rule.

Defining Conflict-Related Sexual Violence (CRSV)

The term “conflict-related sexual violence,” as defined by the United Nations, refers to rape, sexual slavery, forced prostitution, forced pregnancy, forced abortion, enforced sterilization, forced marriage, and any other form of sexual violence of comparable gravity perpetrated against women, men, girls, or boys that is directly or indirectly linked to a conflict.

One in three women worldwide will experience physical or sexual violence in their lifetime — a figure that is far higher in conflict settings where societal norms can quickly break down. According to the UN report Conflict-Related Sexual Violence Against Women and Girls in South Sudan, conflict-related sexual violence even occurs with and around camps of displaced people in South Sudan. Relatedly, as many as 73% of the women and girls have been sexually assaulted, per a Prevent Sexual Violence in Conflict Initiative policy paper by the UK Government.

In the most recent annual report of the UN Secretary General’s Special Representative, 49 parties, a majority of which were non-state actors, had been reported for conflict-related sexual violence, in more than a dozen countries across the Middle East, Asia, Africa, and South America.

“Against the backdrop of ongoing political and security crises, compounded by trends of militarization and the proliferation of arms, sexual violence continued to be employed as a tactic of war, torture and terrorism,” the UN report concluded. “Civilians were disproportionately affected in settings in which actors pursued military interventions at the expense of political processes.”

However, that UN report was released before the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine, so it’s possible that CRSV is even more widespread now.

It’s important for journalists to understand that CRSV is prohibited under international law. Rape and sexual violence are serious violations of international humanitarian law and therefore can constitute war crimes, and since the 1990s it has been recognized that sexual violence can form part of crimes against humanity and as a means of perpetrating genocide. UN Resolution 1325 on Women, Peace and Security passed in 2000, calling on all member states to take action to curb CRSV — and also increase female participation in peacekeeping and conflict resolution as the two are related.

CRSV was first successfully prosecuted as a component of genocide in 1998 by the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda in the case of Taba Mayor Jean Paul Akayesu. That trial found that the sexual violence perpetrated under his orders “was an integral part of the process of destruction, specifically targeting Tutsi women and specifically contributing to their destruction and to the destruction of the Tutsi group as a whole.” However, as Bosnian sexual violence survivors could tell you, CRSV prohibition — and even the widespread reporting of it — does not translate into prevention or accountability.

Nusreta Sivac, a Bosnian judge, was one of 37 women who suffered nightly rapes by Bosnian Serb forces in the Omarska concentration camp in 1992. Image: Courtesy of Ron Haviv, VII

Indeed, the situation has worsened since then. The past decade has seen sexual violence used on a mass scale against Yazidis, the Rohingya people, women and girls in Nigeria, and people from Ethiopia’s Tigray region. Though there have been a few recent successes in domestic courts, and we have seen the innovative use of universal jurisdiction by German courts to prosecute Iraqi abuse of Yazidis and by Gambia to bring Myanmar to the International Court of Justice, prosecutions continue to be very rare, allowing impunity to flourish.

Why Does It Happen?

CRSV is brutal, deliberate, and intended to punish and/or humiliate individuals and their communities. It is usually perpetrated against civilians who are targeted because of their perceived or actual membership in ethnic, religious minority, or political groups and may follow a campaign of dehumanizing them through propaganda. For example, in Rwanda, CRSV was accompanied by characterizations of the Tutsi minority as “cockroaches,” or in Russia where Ukrainians are defamed as Nazis.

It is very effective in clearing an enemy from the area — and cheap. As one militia member told me, perpetrating sexual violence was “cheaper than a Kalashnikov bullet.” CRSV can also be used as a tool to intimidate and punish political opponents’ family members and female human rights defenders.

Sometimes it is used to exact revenge by forces for what happened to their own people or from frustration after failing to achieve military objectives. Often it involves more than one perpetrator — gang rape. I have met victims as young as four months and as old as 83 years old.

As the International Tribunal on Rwanda recognized in the prosecution of Akayesu, it can be part of a strategy of genocide — to either wipe out another population by leaving the women infertile or to change a region’s ethnic balance by impregnating them.

Thousands of children have been born of conflict-related rape, and they are sometimes rejected by the mother since they can serve as a reminder of the worst day of her life. Apart from the emotional trauma, survivors can be left with sexually transmitted infections, including HIV. Some of those raped are so physically traumatized that they are rendered incontinent.

In addition, female victims of CRSV have been abandoned by husbands and families, outcast by their societies, and left destitute. As we said, it is generally the victims who are left to pay the price, while few perpetrators are brought to justice.

Reporting on CRSV Is a Step Toward Accountability

In the past, perhaps because the majority of war correspondents were male, there has been little coverage of this topic. The right questions have not been asked, and even when there has been plenty of evidence, like after World War II, war crimes prosecutors have regarded rape as a side issue, somehow less important than torture or mass killing.

Often, the victims have been reluctant to come forward because of stigma — rape is the one crime where the victims are often made to feel they did something wrong and in many cases even today, such as girls taken by Boko Haram in Nigeria, those who do speak out can end up ostracized by their community.

Yet in the last 10 years, we have seen more and more media attention about the issue, and increasing numbers of women coming forward. Many Yazidis spoke of their ordeal being forced into sex slavery by ISIS fighters. Numerous Rohingya women told of being gang-raped in their villages by Burmese soldiers. Afterwards, though, some of these victims became angry that they told their stories and nothing happened — and they felt used by journalists.

CRSV is no longer accepted as an inevitable side effect of war, thanks to the tireless work of journalists, civil society groups, and survivors themselves. But that hasn’t stopped it. Only by reporting and making people aware of the horror and scale can we make a difference.

Tips and Tools

Sexual violence can be one of the most difficult subjects to report on. Reporters are asking survivors to recount the most painful and intimate ordeal someone can experience. At the same time, local societal norms might make the victim feel they will be shamed or excommunicated if they come forward. The low likelihood of prosecution might also make them reluctant to speak out. In Ukraine, for example, thousands of women have called the CRSV hotline, but only around 160 have lodged official reports.

It goes without saying that the last thing to do is ask the question “Anyone here been raped and speaks English?” which was reportedly posed by a British reporter to Belgian nuns and other European survivors of unrest in eastern Congo in the early 1960s as they disembarked from a US military plane. However in spring 2023 in a recently liberated village near Kyiv where rapes had been reported, I heard TV reporters asking: “Anyone know where there’s a victim?”

Sometimes a conflict reporter will find themself in a place where survivors are fleeing horror and some will want to talk and may even find some relief in doing so. But remember these people can be psychologically and emotionally fragile, and making them relive their experience can retraumatize them or damage future legal proceedings. No one should be asked to talk about this unless they are willing. Nor is there any need to publicly name victims, though, very occasionally, some survivors want to be identified as they feel so strongly and have reported or gone to court. Informed consent is key.

Another section of this guide delves into how journalists should conduct such interviews, but I have spent a lot of time talking to survivors about CRSV and they tell me they want to tell the stories the way they want, where they want, and how. And that it’s also very important who else is in the room at the time. “We had no control over what happened to us, but at least allow us the dignity of control over how we tell it,” one woman who had been assaulted told me.

Ask them about their lives and dreams, not just about the attack. “We don’t just want to be our trauma,” a young Yazidi girl said.

A good starting point for journalists researching this topic is the Murad Code, named after the brave Yazidi advocate and survivor Nadia Murad. It was specifically written for interviewing survivors of CRSV. The Dart Center also has useful guidelines and resources.

Telling stories with sensitivity and respect is possible: for example this CNN photo essay of Rohingya refugees in a camp in Bangladesh preparing to give birth to babies conceived during rape is a powerful example of how you can convey tragedy, pain, and strength without showing faces.

Take care of yourself too. These are hard stories to listen to as well as to tell. And be mindful of the toll this kind of reporting has on your local partner, fixer, or translator, for whom it may be even harder if they are hearing about atrocities in their own country.

Sources

Where possible, it is better to go through trusted third parties working with survivors who can ask their clients if they wish to talk. These can be medical organizations such as the wonderful Panzi Hospital in eastern DRC; counselling agencies such as Medica Zenica in Bosnia; or legal aid groups such as Trial International.

Often first reports of atrocities might emerge internationally from big human rights organizations such as Amnesty International or Human Rights Watch, who can provide contacts on the ground.

Another best practice: go local — find activists, survivor networks, women’s groups and local lawyers or prosecutors. Some children of rape have formed support or activism groups. If people are trying to prosecute their perpetrator, it is much more likely they will want to speak. I like to have a psychologist working with the survivors sit in on interviews to make sure the process is not too overwhelming.

And bear in mind that some NGOs and UN workers have instead sadly taken advantage of the most vulnerable, or may have vested interests in hyping up a situation to get more attention. (There are also instances of aid workers jeopardizing investigations by telling survivors they will receive more support for recounting abuse.)

War in Ukraine

The Russian invasion of Ukraine in late February 2022 shocked the world. As Russian soldiers subsequently pulled out of Bucha and Irpin north of Kyiv that they had briefly occupied, journalists could enter. There, they found bodies in the streets and stories began to emerge of sheer horror.

Many involved rape, often of young girls — and boys. “What we are seeing in Ukraine is a terrifying echo of the Red Army’s mass rapes committed in 1945,” said Antony Beevor, the British military historian. His acclaimed book, “The Fall of Berlin,” estimates that as many as two million women were raped by Soviet soldiers in World War II — not only Germans but also Poles, Hungarians, Serbs, Ukrainians, and even Soviet women.

Across Ukraine, similar tales of horror have emerged — so many that a special hotline set up by the Ombudsman for Human Rights took 1,500 calls within the first six weeks of the invasion last year and was having to operate 24 hours.

Ukraine President Volodymyr Zelenskyy spoke of the rapes in the same breath as torture and killing, unlike many male leaders who have tended to downplay its impact. A father of a teenage girl himself, he fought back tears as he visited Bucha and Irpin in April 2022, later saying, “Hundreds of cases of rape have been recorded, including those of young girls and very young children. Even of a baby!”

In fall 2022, the UN Office of High Commissioner on Human Rights issued an update on the ongoing war in Ukraine. Covering a three-month period from August through October 2022, it included a summary of CRSV allegations. The report “documented 86 cases of CRSV against women, men, and girls, including rape, gang rape, forced nudity and forced public stripping, sexual torture and sexual abuse. The cases occurred in different regions of Ukraine and in a penitentiary facility in the Russian Federation.”

Many international organizations have sent missions to help investigate. Among them has been Karim Khan, chief prosecutor for the International Criminal Court, who was has pledged to improve the court’s poor record on prosecuting sexual violence. Of note: only one person has been successfully prosecuted for this war crime in 20 years.

“Ukraine is an opportunity — a dreadful opportunity,” Khan said in a March 2023 Sunday Times interview. “It represents an opportunity for us to succeed but also a risk because if we can’t show international justice can play a role here when the world seems on a precipice — we might as well be blowing hot air on a cold day.”

Also, notice the compelling use of detail in this Sky News podcast, including this quote: “I remember very well the creak of the table where I was raped, the number of times — five, the smell in the room — smoked sausage mixed with alcohol and sex, the thunder of explosions and the names of books that were on the shelves in front of my face, I read them over and over again while they took turns raping me.”

Case Studies

Abductions and Rape in the Democratic Republic of the Congo

Journalist Lauren Wolfe has written chilling accounts of the desperately poor village of Kavumu in the eastern part of the Democratic Republic of the Congo where children as young as 18 months were being mysteriously abducted from their homes and raped, often left irreparably damaged. Why was it happening and what action could they take?

Wolfe has spent years in conflict zones focusing on violence against women and you can read more of her work. She offers great examples of how to cover these issues with sensitivity.

In 2005, members of Médecins Sans Frontières were operating a clinic in Irumu, eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo, that treated victims of rape, sexually transmitted diseases, and other issues related to sexual violence during that region’s civil war. Image: Courtesy of Ron Haviv, VII

Sexual Slavery of Yazidis

This 2016 investigation by the Associated Press looked into how ISIS established a complex tech infrastructure to engage in widespread human trafficking and sexual slavery of Yazidi women and girls. (Men from these communities were shot while fleeing or killed in mass executions.) In 2021, UN investigators ruled that ISIS had committed genocide against the Yazidis, killing or kidnapping thousands of civilians.

The AP found that ISIS extremists in the far north section of Iraq used ads on the encrypted app Telegram to sell many of the 3,000-plus Yazidi women they captured in 2014. These women and girls, some as young as 12 years old, had been repeatedly raped by members of the terror group, who view the Yazidis as less than human because their religion combines elements of Islam, Christianity, and Zoroastrianism.

The hand of Jwan, 18, a Yazidi woman from Sinjar wearing a watch she stole from the home of an ISIS emir to aid her escape, after being captured and raped by ISIS militants. Khanke, Iraq, 2015. Image: Courtesy of Ali Arkady, VII

I also investigated Yazidi sexual slavery. In a 2020 report, I looked at one southern German state’s efforts to rescue female Yazidis and evacuate them out of Iraq and Syria. In my reporting on the Special Quota Project, I documented its rescue of more than 1,100 formerly enslaved women, and the nearly two-dozen secret shelters across Baden-Württemberg where the survivors have been housed. I was also able to interview several of these Yazidi women, who told me their harrowing experiences of abuse and the long-term psychological trauma that they continue to confront.

Special Focus: Sexual Violence in the Democratic Republic of the Congo

Interview of Ruth Omar, by Olivier Holmey

Ruth Omar has one piece of advice for interviewing victims of sexual violence: “Be human.” The freelance journalist, who has reported for the BBC World Service on the use of rape as a weapon of war in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, says she always makes sure her interviewees feel perfectly at ease in her company. “Think about what those people are going through,” she recommends. “Doing interviews, I just listen to them, I let them feel comfortable.” Only then will they share their stories, she says.

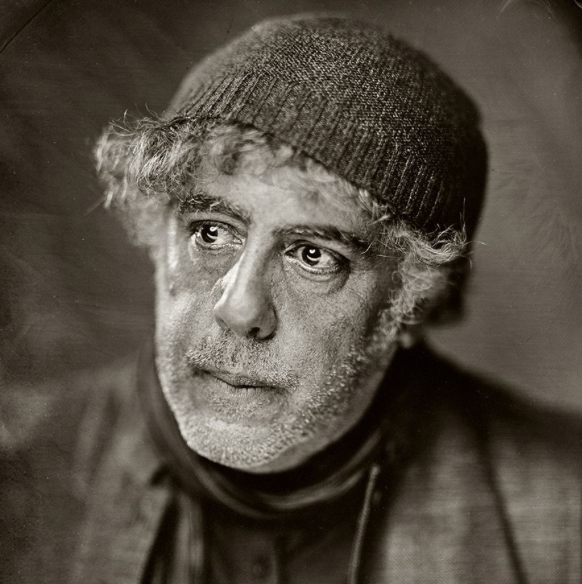

Investigative journalist Ruth Omar. Image: Screenshot, LinkedIn

Omar grew up and lives in Goma, the capital city of North Kivu, a region that has known conflict for decades. She says that sexual violence is widespread in the area, and not only because of the war between the government and rebel forces, including the M23 movement. “Sexual violence is not only connected to war,” she explains. “There are also social, economic, political, and historical dynamics connected to sexual violence. When one is reporting on sexual violence, one needs to draw these connections.”

“Reporting on sexual violence has always been a sensitive issue,” she continues. “It takes so much time to go about it carefully. It requires one to dig deep.”

She tells GIJN that NGOs are essential partners to her reporting. These have included Doctors Without Borders, the UN High Commissioner for Refugees, USAID, and the International Rescue Committee. Not only are these organizations able to introduce Omar to those who have endured sexual violence at the hands of rebel forces, but they are also able to reassure these individuals that they can trust her. NGOs also help keep her safe when she travels to potentially dangerous parts of the country.

Although her reports reveal heart-wrenching stories, Omar also always shines a light on the Congolese activists working hard to address these issues. Only by covering the solutions as well as the problems will readers trust the media and will society change for the better, she argues.

Additional Resources

Investigating Sexual Abuse: An Updated Reporting Guide

Best Practices for Journalists Covering Conflict-Related Sexual Violence

Reporter’s Guide to Investigating War Crimes: Attacks on Civilians

Christina Lamb is a bestselling author and award-winning Chief Foreign Correspondent of the Sunday Times and has reported on conflicts around the world from Afghanistan to Ukraine since 1988. Her work has always focused on what happens to women in conflict. She has written ten books, including co-writing I Am Malala and also Our Bodies, Their Battlefield: What War does to Women, and is a global envoy for the UN’s Education Cannot Wait campaign.

Christina Lamb is a bestselling author and award-winning Chief Foreign Correspondent of the Sunday Times and has reported on conflicts around the world from Afghanistan to Ukraine since 1988. Her work has always focused on what happens to women in conflict. She has written ten books, including co-writing I Am Malala and also Our Bodies, Their Battlefield: What War does to Women, and is a global envoy for the UN’s Education Cannot Wait campaign.

Ron Haviv is a director and co-founder of The VII Foundation and co-founder of VII Photo Agency. In the last three decades, Haviv has covered more than twenty-five conflicts and worked in over one hundred countries. His work, which has won numerous awards, is featured in museums and galleries worldwide.

Ron Haviv is a director and co-founder of The VII Foundation and co-founder of VII Photo Agency. In the last three decades, Haviv has covered more than twenty-five conflicts and worked in over one hundred countries. His work, which has won numerous awards, is featured in museums and galleries worldwide.