A Kurdish guerrilla inspects an unexploded chemical bomb left over from the 1988 Iraqi Army poison gas attack on Halabja that killed as many as 5,000 civilians. Image: Courtesy of Ed Kashi, VII

Editor’s Note: This chapter contains graphic details and is an excerpt from GIJN’s Reporter’s Guide to Investigating War Crimes. Special thanks to Dearbhla Minogue of the Global Legal Action Network for her invaluable advice. The guide will be released in full this September at the Global Investigative Journalism Conference.

In 2018, as regime troops crushed the rebel-held city of Douma in Syria, the videos emerging from the ground were apocalyptic in nature. Fire rained down from above as heavy shelling forced the civilian population underground and into basements, where yellow-green chlorine gas dropped by helicopters suffocated victims in darkness.

The horror of the situation was overwhelming, but it was vital to log each piece of information, noting what weapon was used, and how, in order to identify if and how crimes had potentially occurred.

Weapons are designed to kill people and break things. Their effects can result in death, maiming, and life-long injuries. It is hardly surprising that an interest in weapons and how they work can sometimes be seen as something geeky, weird, or even bloodthirsty. Yet understanding how weapons work and how they can be categorized can be an incredibly important part of understanding what kind of harm is being done in conflict.

One of the crucial questions that a journalist may wish to answer about a particular incident is whether a crime has been committed — and to answer this question, or at least understand the issues surrounding it, it’s also necessary to understand the law around how and when weapons can be used, and when they are restricted or even banned.

There are a plethora of different definitions, rules, and principles which regulate the conduct of armed conflict. These same rules, and other more specific agreements, govern what weapons can and can’t be used, and in what circumstances. In theory the use of all types of weapons is restricted, due to the principles of International Humanitarian Law (IHL) — also known as the Law Of Armed Conflict or the Law of War — as well as Customary International Law (CIL).

- Some types of weapons, such as land mines, cluster munitions, or incendiary weapons like napalm, have specific treaties or customary international law rules which govern or restrict their use. Weapons may be outright prohibited under these treaties, while others may be restricted in the way they are used, for example because of the expected effects they are to have in certain circumstances.

Such treaties are only binding on states which have ratified them. However, legal obligations and many of the prohibitions regarding the use of specific weapons can also “crystallize” as CIL due to consistent and widespread practice by states and their acceptance of this practice as law, resulting in these obligations being applied universally. The International Committee of the Red Cross maintains a database outlining under what circumstances CIL may be applied.

None of the treaties governing the use of weapons have been signed by all governments of the world. If a state has not agreed to a convention or treaty, then it is not breaching any agreement by using a weapon which might be governed by that agreement, except where those rules have crystallized into CIL and as such are universally applicable anyway.

For example, neither Russia nor the United States of America are party to the Convention on Cluster Munitions, and there is no specific CIL prohibition on the use of cluster munitions. As such it is legal for them to stockpile and use cluster munitions, as long as they abide by the principles and restrictions of IHL and CIL.

Of course, there is also an argument that, due to their design and effects, cluster munitions may inherently breach the principles of IHL and CIL, thereby rendering them effectively banned in almost all circumstances anyway.

The ongoing and rapid development of weapons means that they regularly emerge as topics of debate, such as the use of artificial intelligence in weapons systems. In some cases, such as Unmanned Combat Aerial Vehicles (UCAVs), the legality of the use of certain weapons systems may be debated, not necessarily because of the specific effect of that weapon system, but rather due to rules regarding legality of a state using force within the territory of another state.

The large number of rules and principles can often be confusing to those who aren’t familiar either with the various laws or the application of force. Indeed even those who should be familiar with these rules, whether lawyers or soldiers, can and do make decisions that are inconsistent with these rules and principles. Rather than trying to summarize the entirety of the law regarding use of weapons, this chapter will lay out some principles and agreements. It will also address the topic of the use of phosphorus, which can be used to illustrate the identification and legality of the use of both incendiary and chemical weapons.

Resources for Identification

Identification of weapons can sometimes be difficult: many explosions look very similar to each other. However, some weapons, such as incendiary and cluster munitions, have distinctive visual signatures. Many others can be identified by the fragments they leave behind. Fragments like this should not be picked up, but photographs of them, especially including any serial numbers, can provide clues to what they were.

Experts

The most valuable tool for journalists when trying to identify weapons and the legality of their use is a weapons expert. Some media organizations are lucky enough to have such experts near at hand in their newsrooms, but sometimes it may be necessary to reach out to an external expert to get the required information, especially if it’s regarding a more esoteric weapons system.

Contextual Understanding

While it’s unlikely that most journalists will be able to invest the time required to identify weapons from their effects or the fragments they leave behind, it is helpful to have an understanding of how different systems function, and their visual signatures. For distinctive weapons like incendiary or cluster munitions, it’s certainly possible to understand what they could look like, even if it might need an expert to confirm their use.

Websites like CAT-UXO provide an excellent resource on what weapons look like, while reports like the Atlantic Council’s Breaking Aleppo and Breaking Ghouta provide information about what the effect of these weapons can look like.

How Is the Use of Weapons Governed?

At the most basic level, the use of all weapons is restricted by the principles laid out in IHL, including the principles of distinction and proportionality, and the prohibition of causing unnecessary suffering or superfluous injury. States must also ensure in the study, development, acquisition, or adoption of new weapons that their use will not violate IHL. Since 2014, the Arms Trade Treaty, ratified by 113 states, regulates the transfer, including sales and export, of weapons by these states.

The legality of a weapon can depend on how it is used. For example, the GBU-43/B Massive Ordnance Air Blast (MOAB) is one of the most powerful conventional weapons ever made and has an extremely large blast radius. If it were used against a battlegroup assembly area in the middle of a desert during a conventional war, it would arguably be legal use of the weapon.

However, if a MOAB was used in the middle of a city populated by civilians to kill a man armed with a muzzle-loading gunpowder musket, then it would almost certainly breach certain obligations under IHL, such as the principle of proportionality. As such the use of all weapons is inherently restricted to some degree by these principles.

A model of the US GBU-43 Massive Ordnance Air Bomb, or “MOAB,” outside the McAlester Army Ammunition Plant in Oklahoma. Image: Shutterstock

Specific Treaties

The following list of treaties is not exhaustive, however it contains the most prominent examples of such agreements.

- The Ottawa Convention, also known as the Convention on the Prohibition of the Use, Stockpiling, Production and Transfer of Anti-Personnel (AP) Mines and on their Destruction.

This treaty prohibits the use, stockpiling, production and transfer of anti-personnel mines, and includes an obligation to remove anti-personnel minefields from the territory of member states, whoever laid them. It has 133 signatories (suggesting political support) and 164 state parties (states which are legally bound by the treaty).

It defines anti-personnel mines as “a mine designed to be exploded by the presence, proximity or contact of a person and that will incapacitate, injure or kill one or more persons.” It does not govern the use of anti-vehicle mines.

Due to continued use, it cannot be said at this stage that the use of anti-personnel land mines is prohibited under CIL.

This treaty governs the use of certain types of conventional weapons, such as land mines, booby traps, incendiary weapons, and blinding lasers. Note that this convention does not ban the use of most of these weapons, but rather restricts their use. It has four signatories and 126 parties.

Under CIL, there are restrictions on the use of land mines, booby traps, incendiary weapons, and blinding lasers.

Anti-personnel mines found inside an Al-Qaida house in Kabul, Afghanistan. Numerous papers with chemical formulas, weapons, and flight instructions were also found in the building. Image: Courtesy of Ron Haviv, VII

This convention prohibits the use, transfer, production and stockpiling of cluster munitions. It has 108 signatories and 110 state parties.

This treaty defines cluster munitions as “a weapon consisting of a container or dispenser from which many submunitions or bomblets are scattered over wide areas.” It should be noted that there are further, specific definitions within the Convention.

While there are no specific CIL restrictions on the use of cluster munitions, it may be argued that they can be defined as a “weapon that by its nature is indiscriminate,” and so prohibited.

This convention governs disease-causing organisms or toxins which are used to harm or kill humans, animals, or plants. It effectively prohibits the development, production, acquisition, transfer, stockpiling, and use of biological and toxin weapons. It has 185 state parties and four signatory states.

The UN’s World Health Organization defines biological and toxin weapons as: “either microorganisms like virus, bacteria or fungi, or toxic substances produced by living organisms that are produced and released deliberately to cause disease and death in humans, animals or plants.”

Under CIL the use of biological weapons is prohibited.

This convention prohibits the development, production, acquisition, stockpiling, retention, transfer, or use of chemical weapons by state parties. It has 165 signatories and 193 state parties. Only four UN states are not parties: Egypt, Israel, North Korea, and South Sudan.

This treaty defines chemical weapons as: “toxic chemicals and their precursors… munitions and devices, specifically designed to cause death or other harm through the toxic properties of those toxic chemicals… and any equipment specifically designed for use directly in connection with the employment of munitions and devices.”

Under CIL the use of chemical weapons is prohibited. Some chemical agents, such as tear gas, may be lawful in some circumstances, such as for riot control purposes, but may not be used as a method of warfare.

A 54 year-old woman receives care for her wounds in the town At-Ta’mim in Halabja, Iraq, 1991. This woman received her scars during an Iraqi Army mustard gas barrage on the area in 1988, which is believed to be the largest chemical weapons attack directed against a civilian-populated area in history. Image: Courtesy of Ed Kashi, VII

Controversial Weapons

White Phosphorus

In order to illustrate how these conventions might be applied, this chapter includes a case study on the use of white phosphorus, which can be used in war and conflict in several different capacities.

White phosphorus is a chemical that ignites spontaneously when it reacts with oxygen, producing an extremely hot flame and a large amount of dense, white smoke. When it comes in contact with flesh it produces extremely severe burns and is difficult to remove or extinguish.

Reporting on the use of phosphorus can sometimes display a poor grasp of how and why certain weapons are restricted or banned. In various forms (red, white, and black), the element phosphorus can be used in a smoke-producing or illuminating projectiles that are not specifically restricted; as an incendiary weapon governed by the Convention on Certain Conventional Weapons’ or, in very specific contexts, as a chemical weapon governed by the Chemical Weapons Convention. As such, examining where and which kind of phosphorus can and cannot be used is a useful case study.

The most frequent reason for the use of white phosphorus — which is by far the most common type of phosphorus in military munitions — is to produce a smoke screen. The smoke it produces is very thick and screens both visually and in the infrared band, meaning that thermal optics cannot see through it. White phosphorus can also be used for its bright flame, illuminating a particular area.

In both these cases, if all the other principles of IHL and CIL are followed and the intent is to achieve either a screening or illuminating effect, then the use of white phosphorus is perfectly legal.

The primary area of concern relates to the use of white phosphorus as an incendiary weapon. An incendiary weapon is defined by the CCW as “any weapon or munition which is primarily designed to set fire to objects or to cause burn injury to persons through the action of flame, heat, or combination thereof, produced by a chemical reaction of a substance delivered on the target.”

If the user is a member of the CCW then the use of white phosphorus will be governed by that convention. Under the CCW it is prohibited to use incendiary weapons to:

- Make civilians or civilian objects the object of attack;

- Target a military objective within a concentration of civilians by air-delivered incendiary weapons;

- Make any military objective located within a concentration of civilians the object of attack by incendiary weapons other than air-delivered incendiary weapons, except:

- When the military objective is clearly separated from the concentration of civilians;

- Where all feasible precautions are taken with a view to limiting the incendiary effects to the military objective;

- Where the attack avoids or minimizes incidental loss of civilian life, injury to civilians and damage to civilian objects;

- Target forest or plant cover, except where it is used to cover, conceal or camouflage combatants or other military objectives, or are themselves military objectives.

Rule 84 of CIL states: “If incendiary weapons are used, particular care must be taken to avoid, and in any event to minimize, incidental loss of civilian life, injury to civilians and damage to civilian objects.”

As such, the use of white phosphorus as an incendiary weapon is in fact permitted under CCW and CIL in an extremely limited set of circumstances. The reality of war is that most large battles take place in and around population centers and means that it is unlikely, but not impossible, that an incendiary attack is justifiable under the CCW, IHL, and CIL.

Although the definitions above may seem relatively straightforward, there may still be cases where the legality of its use is unclear. For example in 2017, video footage showed white phosphorus munitions being fired into an urban area of Mosul by the US-led coalition. Although this would appear to breach the principle of distinction in IHL as well as the CCW, a statement from the coalition claimed that these munitions were being used to create a smoke screen to hide civilians who were being attacked by ISIS while attempting to flee. Human Rights Watch also noted that in this incident the “the projectiles burst very close to the ground in what seems to be an attempt to minimize the footprint of the effects.”

In this case, it is hard to know what capacity white phosphorus was being used without direct knowledge of all factors of the situation and without knowledge of the effect that the commander intended to have on the target. These elements are necessary to establish whether its use constituted a war crime or other violation of applicable laws. Taken at face value it could easily breach IHL principles such as proportionality and distinction, as well as the CCW itself. However if the statement from the coalition is true, then the use of white phosphorus to create a smoke screen in this case could be argued to be justifiable under various agreements given the circumstances.

White phosphorus can also, in theory, be used as a chemical weapon. The definition of a chemical weapon according to the Chemical Weapons Convention is “a chemical used to cause intentional death or harm through its toxic properties.”

Phosphorus is a pretty nasty chemical by itself, but even when used as an incendiary weapon it is not necessarily a chemical weapon. In order to fulfill the definition under the Chemical Weapons Convention, it must be deployed with the intent to utilize its toxic properties.

Therefore, it is difficult to identify if white phosphorus is being used as a chemical weapon. First, it requires knowledge of the commander’s intent. Second, phosphorus has multiple uses on the battlefield, where it can be used for smoke, illumination, or its incendiary qualities. This is different from agents such as sarin or even chlorine, which only have a single viable use on a battlefield: as a chemical weapon. As such it’s more difficult to disaggregate the effects of white phosphorus and identify if it is being used for its toxic properties.

A clear example of where the use of white phosphorus could be governed by the CWC is if written orders were leaked showing that a commander had ordered their men to blow the smoke from burning white phosphorus into a tunnel system in order to kill or drive out enemy fighters. In this case, it is clearly not being used for illumination, a screening effect, or as an incendiary. It is only being used for its toxic properties, which can incapacitate and kill.

Unmanned Combat Aerial Vehicles (UCAV)

UCAVs, or armed drones, are governed by the same rules as all other weapons. There is currently no specific international agreement governing the use of unmanned vehicles as such, and the law draws no distinction between manned and unmanned platforms. An airstrike which kills 10 civilians at a wedding carried out by a manned F-16 is, legally speaking, essentially the same as an airstrike which kills 10 civilians at a wedding carried out by a Predator drone. The fact that the pilot is sitting several thousand miles away is unlikely to make substantive difference in the law, although there may be considerations regarding actions which may be taken to protect the pilot.

The primary legal controversy over the use of drones relates not to rules of IHL or the actual effect it has on target, but rather the where and how drones are used, according to other international laws regulating the use of force between states. The United Nations Charter prohibits “the threat or use of force against the territorial integrity” of another state. This may include drone strikes, the use of which by one state on the territory of another could be a prima facie breach of the Charter.

There are many examples of the United States carrying out such drone strikes in Pakistan and Yemen, campaigns that also resulted in high numbers of civilian casualties. The United States has justified such strikes under the principle that the targets of such drone strikes represent an “imminent threat” and that the state where the target was located either consents to the use of force or is “unwilling and unable” to take appropriate action to address the threat itself. It is often unclear how the US has evaluated what represents an “imminent threat,” especially since so much of the information regarding these strikes remains classified.

A US Air Force Predator drone takes off from Balad Air Base in Iraq, June 12, 2008. Image: Shutterstock

Some states, such as Iran, have avoided debates regarding the legality of the use of armed drones, or drones modified to become loitering munitions, on the territory of other states by simply refusing to acknowledge that they carried out such attacks.

However, in the case of drones, some argue that the law has lagged behind on what is technologically possible, while others suggest what is needed is clarity on how existing laws apply to such cases. While there are very clearly considerable legal concerns about the use of UCAVs due to their unique capabilities, there is currently no specific international agreement restricting or banning their use.

Case Studies

Israel’s White Phosphorus Bombing Campaign in Gaza

Forensic Architecture (FA), a London-based investigative group that brings a scientific approach to civil society issues, was commissioned in 2012 to examine the Israeli military’s use of white phosphorus munitions during the 2008-09 conflict in the Palestinian territory of Gaza. Using 3D modeling and video analysis, FA found that the Israeli air force repeatedly deployed white phosphorus shells on the urban population, harassing and terrorizing civilians who abandoned entire neighborhoods. After initial denials were contradicted by video evidence, Israel acknowledged using the munition, but claimed that its only purpose was for smoke screening operations. FA ultimately presented its report to both the UN Convention on Conventional Weapons and to the Israeli High Court. While the Israeli military continued to dispute the findings, in 2013 it declared that it would no longer use white phosphorus in urban or populated areas.

US Drone Strikes’ Widespread Civilian Casualties

In 2021, The New York Times published an in-depth series on the widespread failure to prevent civilian casualties in the US military’s use of drone strikes. The Times uncovered hidden US Department of Defense records documenting airstrikes and their impacts in the Middle East stretching back to 2014. These archives revealed the military’s own assessments of nearly 1,300 dead or wounded civilians in Iraq, Afghanistan, and Syria, despite the Pentagon publicly claiming that precision drone strikes had resulted in almost no known civilian casualties. The Times exposé, which was awarded the 2022 Pulitzer Prize for International Reporting, uncovered an internal culture of recklessness in identifying so-called terrorist targets and widespread impunity for members of the military who made documented mistakes that ended up killing innocent men, women, and children.

Additional Resources

Dig into the Open Source Database of Chemical Weapons Attacks in Syria

Reporter’s Guide to Investigating War Crimes: Collecting and Archiving Evidence

Reporter’s Guide to Investigating War Crimes: Open Source Research

Nick Waters is an ex-British Army officer and open source analyst. He is the Justice and Accountability Lead for Bellingcat and has a special interest in the conflicts in Syria, as well as social media, civil society, intelligence and security.

Nick Waters is an ex-British Army officer and open source analyst. He is the Justice and Accountability Lead for Bellingcat and has a special interest in the conflicts in Syria, as well as social media, civil society, intelligence and security.

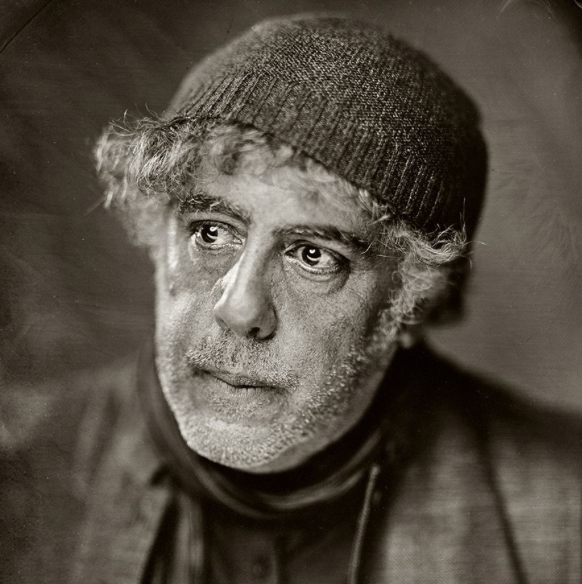

Ron Haviv is a director and co-founder of The VII Foundation and co-founder of VII Photo Agency. In the last three decades, Haviv has covered more than twenty-five conflicts and worked in over one hundred countries. His work, which has won numerous awards, is featured in museums and galleries worldwide.

Ron Haviv is a director and co-founder of The VII Foundation and co-founder of VII Photo Agency. In the last three decades, Haviv has covered more than twenty-five conflicts and worked in over one hundred countries. His work, which has won numerous awards, is featured in museums and galleries worldwide.