Olga Rudenko, seen in the center, in a black jacket, with some of the team of the Kyiv Independent, in their office in the Ukrainian capital in the summer of 2022. Image: Kostyantyn Chernichkin, Kyiv Independent

This is the keynote speech given by Olga Rudenko, the editor-in-chief of the Kyiv Independent, at the Center for Investigative Journalism’s summer conference in London. It has been abridged and edited for length and clarity.

In November 2021, there were up to 50 people on the Kyiv Post staff. They came to work one day and learned that they were fired, effective immediately. All of them. The owner made it clear he was recruiting key staff to replace us with more obedient people that would not get him into trouble.

This is the manifestation of how things are done in Ukraine. Rich owners tell journalists what to do, tell newspapers what to write. Journalists are disposable, they don’t have a say. That’s what I was told by more experienced colleagues: Make your peace with it, this is how things are done.

We had a choice. Of the 50 people that were fired, over 30 were in the newsroom. We all had job offers that first day. We could leave and get a good position somewhere else, continue our lives, and just remember this adventure we once had. Or we could try to fight back.

Fighting back made very little sense from a practical standpoint. We had no money. There is, to my knowledge, no history of journalists launching a publication in Ukraine and making it sustainable, and the owner of the Kyiv Post had the money to hire the best people for the new Post, if he wanted to. But we thought if we just went away, then we accept that this is how things are done. Then we agree that, yes, money rules all. They win, we lose.

We were young and stupid enough to not want to accept that, so we decided: We are going to try and launch a publication of our own doing the same thing we were doing at the Kyiv Post, writing about Ukraine in English. Without a rich owner, without money, or clear ideas about how to make money. Just because we can’t not try. If we don’t then we surrender and let the bad guys win. My thinking was: it’s very scary to do it, I was putting my reputation at stake. If I fail, it makes me a failure. I was thinking, if we try, one year from now we either succeed or we put up a good fight. And we would be on the right side of history.

We launched the Kyiv Independent three days after we were fired from the Kyiv Post. It wasn’t named that yet — the name would come a couple of weeks later. People ask what was the hardest part, and picking the name was by far the hardest part. We set up a committee to pick the name: huge mistake. There’s no perfect name but any name you will learn to love. We ended up with the Kyiv Independent. We launched our website three weeks after being fired from the Kyiv Post. We launched the newsletter Ukraine Daily, our first product, one week after being fired. We got some emergency funding from the European Endowment for Democracy and we started a membership program.

Rudenko giving the keynote address at the 2023 summer conference of the Centre for Investigative Journalism in London. Image: Juliet Ferguson, CIJ

We decided we were going to explore every ethical way of supporting our reporting. A key one was to try to get our readers to support us. We wanted everything in the open, so instead of a paywall, we launched a membership program. On the surface it was great. Publicly, many people pledged to support us. The background was not as rosy. Almost no one was coming to the website at the beginning. On some days we had fewer people coming on the website than people donating to us. It was a rocky start.

For three months we worked very very hard, no time off, the usual start-up thing. In the background, the rumors were coming in about a possible Russian invasion of Ukraine. Troops massing near the Ukraine border. We thought it could be bluffing, intimidation. Something I learned: it’s incredibly hard to make yourself believe that something so abnormal can happen even when all the signs point to the fact that it will happen. Your mind really shuts down and says “no.” Up to the last minute, I thought it was not going to happen.

In early February 2022, we moved into our first office in Kyiv: two-and-a-half tiny rooms, but we were really happy. Our first general meeting in the new office discussed: Is Russia going to invade Ukraine and what do we do if it does? We didn’t have the resources to relocate all staff to western Ukraine. We asked members of staff to make the decision about whether they would stay in Kyiv, in Ukraine, or leave the country. I remember one saying “I’m going to stay,” and a colleague replying: “Make sure you know what you are talking about. If you are a journalist in Kyiv and Russia invades the city it can be a death sentence to you.” These were the kinds of conversations we were having.

Then the morning of February 24 came. The day before, I left the office around 3 a.m. I was in a taxi riding home when I read that [US Secretary of State] Antony Blinken was saying the invasion is going to happen. When I came home the Kremlin started broadcasting an address by [Russian President] Vladimir Putin. As he is speaking we are texting each other in our work Slack channel. Someone said: this doesn’t sound like he is talking about something that is just going to happen in eastern Ukraine. This is not an escalation, he is about to announce war. So I pre-wrote several paragraphs of a news story, with the headline: Putin Declares War On Ukraine. I had it in a draft, praying I did not have to publish it. Then he ends his video address by saying: “We are starting a special military operation in Ukraine.” We published the story — saying Putin announces war — and immediately we started hearing explosions.

All I could understand was that it was coming from the sky. I did not know how air attacks work. At that time the only association I had at that moment was the bombings of World War II. After hearing this hateful, hateful speech about Ukrainians and then hearing that from the sky, I thought: the road ends here. This is how I die, how we all die. Kind of anti-climactic to be killed by Russia in my own flat in Kyiv, but I guess that’s it. At the same time, all around the city, my colleagues were thinking the same thing. We did what we know how to do: opened up our laptops and started writing. Things were happening very fast. We heard the explosions, we heard Russia was attacking key military sites, airfields. Videos started popping up of troops entering Ukraine. It was an invasion from all sides.

The next couple of days are all kind of a blur. Some of the team members left Kyiv, some stayed, some decided for their safety they needed to leave the country temporarily. We all continued to work, then some days later something strange began to happen; we are in this state of shock, barely sleeping, just writing, writing, writing. Then someone says: Did you see how many Twitter followers we have? It turns out the numbers went from 30,000 to one million in the week after the invasion, then to two million where we are now.

The same was happening to the website. Then journalists started calling, asking to interview us, about the Kyiv Independent. That was overwhelming. Then a couple of months later Forbes did their annual 30 Under 30 Europe list, and four are people from the Kyiv Independent. Then there is a call from Time magazine, that they want me to be on the cover. I say no at first then they talk me into it. So a few months into the war, I raise my head from the computer, look around, and realize we are going to make it. It looks like we are a success.

Investigations in Times of War

Summer started and things in Kyiv were beginning to feel normal. Kyiv was kind of calm, though there was active fighting in other parts of Ukraine. I was just starting to breathe again when the next challenge comes. A journalist comes to me and says she has a tip for an investigative story and she needs to talk to me about it because it’s a risky one. She has information that some really bad things are happening in one of the units of the Ukrainian army, specifically in the International Legion, formed from foreigners who wanted to volunteer to fight for Ukraine.

Sources were telling us there was quite a bit of misconduct, mismanagement, and some abuse by commanders. To top it off, one of the commanders is a former Polish gangster wanted in Poland and under a criminal investigation in Ukraine as well.

The trouble with the story was that, at the time, investigative journalism in Ukraine was kind of on pause. All that everybody was focusing on was investigating Russian war crimes. No one was even thinking about investigating the Ukrainian military. We had this overwhelming feeling that we are in the same boat, the military are defending us, they are untouchable. We worried that if we published the story… it can tarnish the image of Ukraine at a time when we rely on our allies for aid, weapons, and funding. We can be labeled traitors at home. We can face bullying or actual prosecution since Ukraine is under martial law, which gives a lot of freedom to the government when it comes to the press. The third threat was that the main protagonist of the story is allegedly a gangster who has access to a lot of weapons at the moment. What if he wants to go after the reporters of the story? Journalists have been killed in Ukraine, it’s not something that has never happened.

This was a huge, very important test for us. We decided we were going to run the story doing our best possible job. We are going to verify sources, we are going to be very diligent, but we are going to run the story. Why? We don’t believe in self-censorship, and we don’t think war is an excuse for that. We believe shining light on misconduct in the Ukrainian military even during war is in the long run helping Ukraine. And we were ready to take risks. A couple of days before publication, I was sitting on the floor of my kitchen with a final printout of the story, 18 pages, and I was having a bit of a panic attack. All those risks dawned on me. I was fearing for the safety of the journalists, of the possible implications for them, and for the Kyiv Independent. But we ran the story and ran the second part a few months later. The second part included new allegations, including the misappropriation of weapons, which is a very dangerous topic.

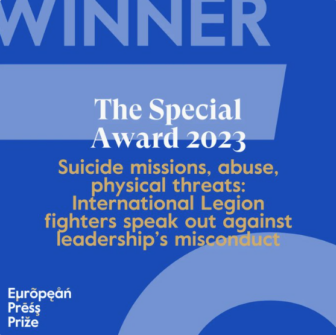

The Kyiv Independent’s uncompromising look at corruption and abuse inside a Ukrainian military unit won a special 2022 European Press Prize. Image: Screenshot, European Press Prize

About three weeks ago, this story won the European Press Prize, one of the most prestigious awards you can get in Europe. I cried when I learned because I remembered sitting on the floor of my kitchen panicking about it, I remembered all the strength we needed to publish this story, and I felt like it kind of paid off. What we did not see was an official reaction from the Ukrainian authorities. From what we know, the people implicated in the story are still in the International Legion. We are still waiting for that to change.

Building a Sustainable Operation

We had this early success, the kind of success that was unheard of for Ukrainian media, but what now? We were in a very precarious moment — we are still in this moment, I think — where you can make the mistake of relaxing and saying ‘OK, this has been great, we are a success, done, check.’ We don’t want to be a short-lived accidental success story. We want the Kyiv Independent to be there when the war ends. When the reconstruction of Ukraine begins. We want to cover that. We want to be the window of the world into Ukraine for many years to come. It took some humility to sit down, look around, and say: ‘Great but now we have to work even more. To preserve what we’ve got. To use this to make this organization sustainable. To go beyond this early attention boost and create something that’s here for many years.’

It was not easy after the first few months. The initial boost we got from people donating, following us, began to wind down. That’s when we had to start working on boring things like a marketing strategy, community development, how to reach more people, how to retain people. It sounds boring, but it wasn’t. We have learned to enjoy it and have managed to overcome the trend and are still growing in page views and members. Now we have approximately 10,000 members and we are fighting to get more. This slow painful growth that came in the last nine months or so is no less of an exciting journey than the explosive growth of the first few months.

We are now a team of 40 people; most of them very young. I’m 34 and I’m one of the oldest. We still face a lot of tough challenges. One of the toughest ones for me is when to authorize reporting trips by staff to the front line. I have no experience as a war reporter, I have to make these decisions based on very little information. My biggest fear is having one day to make a call to someone’s family to tell them someone they loved was killed or injured while on assignment.

One of our journalists, Artur Korniienko, a wonderful culture reporter, volunteered to join the military on the first day of the war. He is still serving. He is now in eastern Ukraine, he has been in some of the hottest spots. When I’m asked what the future looks like, I don’t have a good answer, but one thing I picture very clearly: Artur back in Kyiv, writing about culture.

I thought I would end with a few lessons I learned from this experience:

- Being a journalist covering a war that’s happening in your own country is both a blessing and a curse. A curse because you have to stay so close to everything, you have to watch videos of the atrocities all the time. The number one mental health advice that people in Ukraine give to each other is to turn off from the news for several days. We can’t afford to do that. At the same time, being a journalist in these circumstances is also kind of a blessing because it gives you a certain framework to look at these atrocities. Last year, when we saw what the Russians did in Bucha, the massacring of civilians, the only thing that got me through those days was that I was looking at those pictures thinking: How do we cover it? Do we send someone there? Who? What’s the next story? That gives you some distance, some mechanism to deal with it. You have a feeling as a journalist you are in a way part of the fight. You are on the good side. You can do something, you are participating in your own way.

- There’s no perfect time. I always thought that if I was ever to launch a publication it would be in the perfect circumstances: I would take some time off, think about the perfect name, the staff, plan everything out. But we were pushed into launching the Kyiv Independent and it worked out. When it happened I was five weeks into a sabbatical: I felt like I burned out after 10 years in a weekly newspaper. I took time off and thought I would not work for a few months, look after my mental health, my physical health. That did not happen. That’s alright. It taught me there’s no perfect time.

- Every person is stronger than they think they are. When we started the Kyiv Independent we had a wonderful lifestyle reporter on the team. She was the lifestyle guru: she knew every restaurant, every club, every fashion designer. Since the full-scale war started, she has been focusing on stories of human suffering. She speaks to parents who’ve lost their children. People who had their whole family killed. Her name is Daria Shulzhenko. She has written some of the most painful and important stories of the war. I would never have thought a couple of years ago she would want to do something like that, but she’s one of those many cases where people turned out to be amazingly strong.

- Sticking to what you believe in — your principles — and standing up for them always pays off down the road. If we decided to obey the [Kyiv Post] owner and stop writing stories about the prosecutor general, it wouldn’t be a big deal, right? Stay off this one official and we would still be in a safe and comfortable position. But we would never have launched the Kyiv Independent, never had the success we had, or been on this journey together.

- Another very important lesson is you always, always have a choice. When somebody tries to show you that you are powerless, you can choose not to be shaped by external circumstances. When we were launching the Kyiv Independent — instead of succumbing to pressure from the Kyiv Post owner — someone from the journalism community told me we were behaving like children, like we were born yesterday. He said: ‘This is how things are done’ and started naming other news outlets in Ukraine, good ones, he said: ‘Don’t you think that’s how they do it? They also get told not to write about someone.’ We decided — we don’t care. We have a choice, we don’t have to go along with it. If we think things have to be done differently, we deserve to try. We tried and it paid off.

It sometimes strikes me how the story of the Kyiv Independent has some parallels to the story of Ukraine itself. Standing up for your beliefs. Standing up against a stronger opponent. Succeeding against the odds. Except that no one was killed building the Kyiv Independent and many of my fellow Ukrainians are getting killed every day for exactly these values — for saying Ukraine has the right to decide its own future.

I always say, and it’s not wishful thinking but something I truly believe — no, something that I know: I know Ukraine is going to win this war. I don’t know the price, don’t know when, but Ukraine is going to win… and my work is now focused on making sure that we at the Kyiv Independent do the best possible job covering this amazing story for the world to see. And that after the victory, we will be there to cover the story of the rebuilding of Ukraine.

Additional Resources

10 Tips for Founding a Successful Investigative Startup

One Year of War: How Watchdog Journalists Have Dug Into Russia’s Invasion of Ukraine

Want to Launch a Membership Program? Here Are 6 Things to Consider

Olga Rudenko is the editor-in-chief of the Kyiv Independent, an award-winning media start-up launched in November 2021 by the former editorial team of the Kyiv Post. Rudenko — the former deputy chief editor of the Kyiv Post — was a fellow at the Chicago Booth School of Business in 2021. She was featured on the cover of Time magazine in May 2022 as one of the publication’s Next Generation Leaders, and won the Women of Europe award in the “Woman in Action” category in December 2022.

Olga Rudenko is the editor-in-chief of the Kyiv Independent, an award-winning media start-up launched in November 2021 by the former editorial team of the Kyiv Post. Rudenko — the former deputy chief editor of the Kyiv Post — was a fellow at the Chicago Booth School of Business in 2021. She was featured on the cover of Time magazine in May 2022 as one of the publication’s Next Generation Leaders, and won the Women of Europe award in the “Woman in Action” category in December 2022.