A police officer stands guard at San Martin Square in the Peruvian capital, Lima. The country has seen waves of protests since the latest political crisis erupted in December. Image: Shutterstock

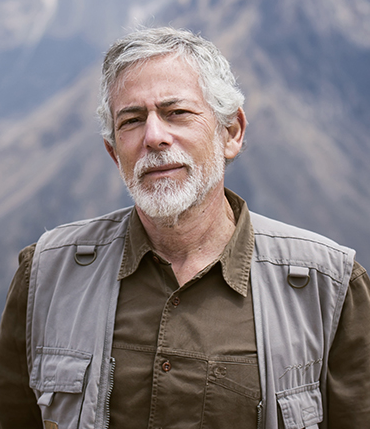

“There is no alternative other than to face all the disinformation campaigns, the slander, and the threats,” says Gustavo Gorriti, who leads a team of investigative journalists at the Peruvian digital outlet IDL-Reporteros, which is a GIJN member. “Defending the investigations means defending the truth.”

But just hours after we speak, more than 50 far-right activists attacked the IDL-Reporteros headquarters in Lima, insulting and threatening Gorriti, releasing flares and fireworks, and throwing garbage bags and tree branches.

This attack — the fourth this year — came two days after the outlet published a report related to the “Lava Jato” case, a sprawling corruption investigation that has been playing out across Latin America in recent years.

In a twist to the story, a handful of media outlets had tried to implicate Gorriti and the head of another newspaper in the scandal, accusing them of having ties to the directors of the controversial Brazilian construction company accused of paying million-dollar bribes to obtain contracts across the continent.

The IDL-Reporteros story — Anatomy of a Defamation — dug into how these outlets had created “clumsy and cretinous” rumors in order to discredit journalists like Gorritti.

This is just one example of recent attacks on the press in Peru, which has plummeted down the Reporters without Borders Press Freedom rankings — going from 77th place in 2022, to 110th position this year. RSF warns that journalists in the country “are often harassed or attacked by security forces” and that “some previously reliable media outlets have started publishing disinformation.”

Investigations into corruption, mismanagement of public funds, and human rights violations in Peru have made journalists and independent media outlets the target of attacks. Reporters have been assaulted while covering protests, and been on the receiving end of legal proceedings, smear campaigns, and attacks by extremist groups.

Gustavo Gorriti, of IDL-Reporteros leads one of the last few investigative reporting teams in Peru. Image: Screenshot, IDL-Reporteros

The Journalist’s Human Rights Office (OFIP) in Peru – which is linked to the reporting union — has detailed a number of assaults on reporters trying to cover recent large-scale social protests. They warned that 94 reporters were attacked in January 2023 — some were injured by protesters, they report, others by “police agents.” The month before that the figure was 59. On January 7, the Committee to Protect Journalists reported that “police officers threatened to kill Aldair Mejía, a photographer for the Spanish news agency EFE who was covering the anti-government demonstrations… Officers later shot Mejía in the leg with pellets, breaking his right tibia, according to those sources.”

Faced with criticism for a new attack on press freedom in Peru, Congress just backed down and shelved a bill to increase the penalties on defamation and slander. The proposed law’s objective was to intimidate the press, according to an analysis from the National Association of Journalists, a union that has registered 146 cases of journalists being brought before judicial authorities for retribution against their investigations.

A Press Crisis — and a Political Crisis

These challenges go hand in hand with Peru’s many political crises. Turnover at the top has reached epic proportions, with six presidents in the last six years. Three former leaders are imprisoned in the same jail: Alberto Fujimori, for human rights violations, Alejandro Toledo, who is facing corruption charges, and Pedro Castillo, who is accused of illegally attempting to dissolve Congress at the end of last year.

Since then, 50 people have been killed and hundreds injured during protests against the government of Dina Boluarte, who succeeded Castillo.

Outraged and concerned, journalists at GIJN member Convoca — where I work as a regional editor — and from other independent media outlets started to investigate how these deaths occurred and published videos, testimonies, and documents about the violence. Among our reports are investigations into alleged extrajudicial executions committed by agents of the police and the armed forces in the country’s poorest and most forgotten regions. The president has been accused of inaction, even by some former ministers, of “washing her hands” of any responsibility.

With the press under attack, investigative journalism has almost disappeared from the mainstream media. As a result, nonprofit digital outlets that do not depend on state or private advertising, such as IDL-Reporteros, Convoca, Ojo Público, and Salud con Lupa, have had to pick up the baton.

On the Trail of Corruption Through Crises and COVID

Nuns walk past a church in Lima, closed because of the coronavirus pandemic. Image: Shutterstock

Although investigative journalists in Peru face many challenges, there are also opportunities, especially with “mega cases” regarding corruption that crosses borders, and we understand now that it is better to be allies than rivals.

Investigating corruption is challenging because political and private powers use sophisticated mechanisms to hide corrupt practices, as Convoca founder and director Milagros Salazar often says. So to investigate corruption networks that have a major impact on citizens’ lives, we at Convoca weave collaborative networks, working with independent journalists, media outlets, and journalistic organizations.

We specialize in investigative journalism and data analysis, and understand that our reports have a greater impact when we join forces, as in the Investigating Lava Jato project, where we covered corruption cases involving the construction corruption scandal in Peru but also in Brazil, Argentina, Angola, Bolivia, and Colombia, among other countries. We also worked across borders for our project Vigila la Pandemia (Monitor the Pandemic), which dug into the misuse of public funds in the fight against COVID-19 in Latin America.

Image: GIJN

The coronavirus pandemic hit Latin America hard, but even as the crisis recedes, there is still scope to investigate. Peru saw 220,000 deaths — and the anti-corruption public prosecutor’s office is investigating if masks, mechanic ventilators, soap, and alcohol were overpriced, impacting how the public health system served the sick. Although the World Health Organization has declared the end of the emergency, deaths from the virus continue. In the last week of May, Peruvian health authorities reported 62 deaths, mostly of unvaccinated older adults.

On a more traditional follow-the-money note, journalists across the country have been investigating public funding. Intense rains earlier this year left thousands of people homeless, many of them in regions that were hit by flooding in 2017. Back then, sizable government funds were promised for reconstruction and prevention schemes, but the works were either poorly executed, yet to be finished, or in some cases, haven’t even been started. As a result, more than 800 state officials have been implicated in acts of corruption.

If investigative journalism is difficult to carry out in Lima, Peru’s capital, it is all the more so in the country’s interior. This is why we have also formed collaborative networks with local journalists and media outlets, in order to learn from them and support them in the dissemination of their reports. Through an itinerant newsroom, which we call “Investigatour,” our team travels to remote regions like the Amazon, accompanying reporters in the far corners of Peru for research and data analysis.

Peruvian investigative site Convoca launched an itinerant newsroom project “Investigator” to report on issues out in the country’s more remote regions. Image: Screenshot, Convoca

Press Freedom Issues Across the Region

Looking — and working — across the continent, we see that the difficulties we face in Peru are not unique. In Ecuador, reporters face challenges from the state, and from organized crime groups that have killed journalists and forced others to leave the country, warns Christian Zurita, founder of the Periodismo de Investigación platform, an investigative journalism lab.

It’s important, Zurita says, that the press is “not forced into censorship and silence, as has happened in the last 15 years in Central America, which is the great mirror in which we have to look at ourselves.”

For Óscar Martínez, editor-in-chief of El Salvador’s digital newspaper El Faro, investigating corruption in the region is ever more complicated due to the persecution of journalists and their sources, online harassment from “troll farms,” and the blocking of nearly all public information.

Despite the wave of persecution that has driven many journalists from Guatemala, Nicaragua, and El Salvador into exile, Martínez is optimistic: thanks to leaks and “the courage of some sources who decide to speak up, we have never carried out more corruption investigations than since Nayib Bukele came to power,” he says, speaking about the controversial president of El Salvador.

In Central America, to confront the authoritarianism of governments that persecute and criminalize those who attack power, journalists from Nicaragua, El Salvador, Costa Rica, Honduras, and Guatemala came together last year to create the Central American Network of Journalists. “Silence is not an option,” they warned in their first manifesto.

In Peru, the situation for journalists has not improved despite warnings from various international organizations about attacks on press freedom. The challenges of investigating corruption, human rights violations, and other serious problems, in the midst of the political and social crisis, are as great as they have ever been. None of this, however, will stop us.

Additional Resources

Under Attack: El Faro’s Gutsy Reporting in Latin America

In a Hostile Climate, Guatemala’s Journalists Fear the Law Being Turned Against Them

Editor’s Pick: 2022’s Best Investigative Stories from Latin America

Elena Miranda is a Peruvian journalist who lives in Lima. She is a regional editor at Convoca, a portal for investigative journalism and data analysis. She has worked in the newspapers Correo, Ojo, Perú 21, Liberación, and La República.