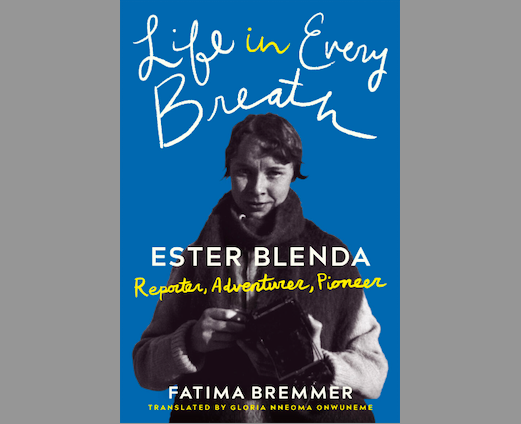

“Life in Every Breath,” written by Fatima Bremmer, tells the story of Sweden’s first female investigative journalist, Ester Blenda Nordström. Image: Screenshot

“Life in Every Breath” tells the story of Sweden’s Ester Blenda Nordström — a woman who in the early 20th Century went undercover to expose working conditions on rural farms, the difficult journeys of migrants traveling to the United States, and to explore the life of the country’s Indigenous Sami community. The book was written by journalist and author Fatima Bremmer, who won Sweden’s top literary award — the August Prize — for her work. The text below consists of excerpts from the book, which was recently published in translation, reprinted here with the author’s permission.

It had felt like such a fun idea at first. An adventure. And Stomberg, editor at the national daily Svenska Dagbladet, had been instantly intrigued when Ester told him about her unique holiday plans, having caught a whiff of a scintillating story with his experienced nose for news. Ester was his bravest reporter. She did the unexpected, and the readers loved it. Her reports and columns, all signed “Bansai,” had become topics of conversation all around the country. Among other journalists, she was known for being outspoken and bold. Ester liked it. It was a role that appealed to her.

Instant employment for A MAID Accustomed to performing household chores and willing and able to milk cows. Taninge Farm, General Delivery Nyköping Farmer Anton Holtz’s job ad for a new maid at Jogersta North Farm; excerpt from A Newswoman for a Maid — Rebuttal by a Farmer in Taninge.

It was sheer coincidence that had brought together this particular advertisement for a maid vacancy and the southbound train on which the 23-year-old Ester Nordström was sitting, on her way to Sörmland County, not feeling quite as confident and excited as she would have liked. There were countless similar vacancies around the country; it had been simply a matter of choosing one of the many farmers in desperate need of female servants. Ester herself had written articles about the so-called maid problem; it was a topic that had already been hotly debated for years.

In one of her interviews, she had quoted a woman saying that “it’s no wonder that young women don’t want to become maids nowadays. They’re all basically forced to become slaves.” She had also been closely following the Emigration Commission, a significant undertaking that politicians began after the Swedish exodus. Between 1851 and 1910, nearly one million Swedes had left for the other side of the Atlantic, in pursuit of happiness and a new life. Many were young women of working age. They preferred to move to America or take up jobs in city factories than work on some farm in their own home country. The commission had, among other things, established that emigration “deprives the agricultural industry of its required workforce.”

According to the Swedish Master and Servant Act of 1833, farmers had the power to independently decide on what “suitable” working hours meant and could exercise the same rights over their employees as they could over their own family. They even had the legal right to use corporal punishment on servants under the age of 16. And yet, the commission remained unable to identify a clear cause for the dire shortage of maids. It had been blamed on everything from modern notions of equality to the socialist movement. A comparison of the treatment of maids in Swedish and American households had shown that Swedish housewives were overly strict whereas affluent US families welcomed Swedish maids with open arms.

Ester had decided to do what no other Swedish reporter had done before: Dressed as a maid, she was going to take a job on a farm and see for herself why young women were fleeing these maid vacancies. She had to become one of them in order to be able to report their reality as faithfully as possible.

Journalist Fatima Bremmer received the August Prize for her book on Ester Blenda Nordström. Image: Screenshot

The train rolled along. It was the beginning of a journey that would make Ester Nordström Sweden’s most famous journalist and lead her out into the world on near-impossible adventures. In time, she would go on to use her pen to help overthrow a Swedish government and save thousands from starvation in the Finnish Civil War. She would live in a Sami collective in Lapland for six months and ride a mule on the narrow, dusty mountain trails between Argentina and Chile. She would walk around the ruins left behind by a devastating earthquake in Japan and travel like the train hoppers in America, clinging to the brake rods under a rushing freight train.

She would go on to fight for women’s suffrage alongside Sweden’s most prominent feminists and suffrage activists and take part in an expedition lasting several years among wild bears and rumbling volcanoes in Siberia. As a pioneering motorcyclist, she would show the world that women, too, could ride and love fast vehicles. The girls’ book series created by Ester Blenda Nordström would not only be widely celebrated; it would change the entire genre and serve as clear inspiration for the greatest works of world-famous children’s author Astrid Lindgren. In the end, the future maid would even become a farmer running her own farm.

It all started here.

The dime novel she’d bought to pass the time on her four-hour journey remained untouched in her handbag by the time the train rolled into the small town of Nyköping. She sensed it was her employer as soon as she saw the man on the carriage fastened to a yellow mare. Farmer Anton Holtz gave her a firm handshake on the courtyard just outside the train station and passed her the reins.

****

Undercover

Twenty cows were waiting to be milked. Ester gulped heavily. She thought she had prepared so well for this role. She’d thought about how she would talk, behave, the chores she would be given. Now, she was seated on a milking stool in front of a huge cow and had to make every movement seem second nature. People could be deceived; cows could not. Ester knew this all too well. They were sensitive to unfamiliar hands and might refuse to let down any milk. If things got bad enough, they could even take to kicking and screaming.

The shiny, well-groomed animals impatiently stomped around their stalls on the clean-swept cement floor. Sigrid [her fellow maid] was sitting on her own stool a bit farther down, humming a polka tune to the rhythm of her hand movements. Ester took hold of the cow’s teats. When she realized that she actually remembered how to make the lukewarm milk stream down from the udder, she sighed with relief. The sharp smell of manure, the stillness, and the barn’s warmth caused a sense of unexpected calm to spread within her.

Two hours later, her arms felt numb and swollen. Her hands ached, and the first signs of blisters made themselves known on her fingers. They moved on to the pigsty. Now, the pigs and 22 chickens had to be fed. Mixing up the thick mass of potatoes, wheat bran, and grits took work. Hunger pierced Ester’s belly. A while later, once the farmhands had left the table, the maids had their own breakfast. Herring, potatoes, and whole-meal rye bread with margarine had never tasted so good. To wash it down, they drank the cream from separated skimmed milk. Ester’s cup had a crack in it.

Ida [the mistress of the house] entered the room and smiled wide. She sat down at the large folding table and poured herself a cup. She was carrying her youngest in her arms; the girl was only eight months old. The infant was fed with mash consisting of a chewed-up biscuit mixed with coffee, while the new maid was asked whether the cows had been difficult to milk that morning, and whether Ester also had potatoes and herring for breakfast back home. Ester mumbled her answers, trying to speak and express herself the way she figured a maid might.

Ester’s replies were her first lies of the day, and they were quickly followed by more, because Ida kept asking questions. About the division of labor on the farm where Ester claimed to have grown up; about whether she’d ever visited Stockholm or been for a ride in a real car.

****

Keeping Up Appearances

She wondered how to go about washing herself and brushing her teeth in the morning. No one in the house seemed to make any effort to cleanse themselves, neither body nor mouth. At one point, when no one was watching, she sneaked out the door and walked down the bumpy path leading to the barn where the water pump stood. The heavy clogs sank into the dirt. Sharp pebbles found their way in and immediately got stuck under the soles of her feet. Ester rinsed off with rapid movements; the water was icy cold. She froze as soon as she heard Sigrid ask whether she’d lost her mind or simply thought herself “so fancy” that she needed to wash herself on a regular Thursday. Before she could even come up with a response, Sigrid had gone back inside. Ester exhaled. She had learned her lesson: no more washing herself before the weekend.

By 9:00 am, they had already served breakfast to the four resident loggers and the children. All rooms except the parlor — the family’s pride and joy with its sky-blue panel sofa, desk, and walnut chest of drawers with a mirror — were thoroughly swept and dusted.

Next, Ester was urged to sit at the loom. The house needed new sheets. She carefully stepped on the squeaky treadles. On the couch behind her lay the master of the house, wearing a leather vest and stockings, and reading a copy of the weekly magazine Vecko-Journalen. A few years later, Ester would become one of that very same newspaper’s most important and prominent writers, a nationally recognized and acclaimed star reporter traveling around the world and reporting back to Sweden. But for now, she was seated at a loom on a farm in the depths of Sörmland County, pedaling and beating with all her might, and thanking the gods for the little she already knew about weaving.

****

Asking Questions

Ester had kept a low profile ever since Ida’s cross-examination about her family, and ever since Sigrid caught her by the water pump. She focused on trying to learn all the daily routines. She had carefully copied Sigrid in everything from her dialect to her technique of scrubbing her face with soap on Saturdays without subsequently rinsing it, to make it as shiny as possible.

But at the same time, Ester tried to observe everything that was said and done on the farm, without being too intrusive or asking questions that a maid wasn’t supposed to ask. She tried to memorize almost everything that she saw and heard, from the most mundane chores to differences in how maids and farmhands were treated. She thought of herself as a camera capturing reality. And all the while, in this tiny village in Sörmland, people were completely unaware that Bansai, one of the capital city’s most daring reporters, was currently paying them a visit. That pseudonym still meant nothing to them. The topics of conversation around the Jogersta North Farm table included neither world nor national news. Newspapers weren’t things that people in the house spent money on, with the exception of the odd copy of Vecko-Journalen — or a lottery ticket whenever there was a huge jackpot out. Everyone — the farmhands, the forest workers, and the Holtz couple — would then get involved. Even Sigrid would invest some money for a quarter of a ticket. She dreamed of buying a velocipede.

During a walk, when Sigrid shared that she had used only ten kronor of her salary in the last six months to be able to buy a single ticket in the near future, Ester saw her chance to ask Sigrid what she earned. Sigrid replied, “One hundred eighty kronor a year,” and went on to say that she also planned to buy a summer coat and a hat a little later. Ester was shocked to realize that this amounted to only fifteen kronor a month. Their working days were at least sixteen hours long, and they had only a few hours off each week.

Ester had discussed the issue of salary many times with her female journalist colleagues in Stockholm. They were few in number, barely a dozen, and they earned about half as much as the 30 men. The dissatisfaction had been brewing for several years, but even they would get around 150 kronor a month. She looked at Sigrid with a mixture of pity and complete admiration.

****

The Exposé

The tears burned behind her eyelids as she left the farm and traveled back to Stockholm and her place at the editorial office. She was already gripped with doubt.

When I came back, I had no desire to write at all [. . .] It was only the promise of an additional month of vacation, as compensation for the month as a maid, that drove me to do it. Such an offer was, of course, impossible to resist.

-

- From an interview with Ester Blenda Nordström in Dagens Nyheter, by the journalist signed “Clementine,” May 17, 1931.

The tales that began with the article below seem to have been written by one of Svenska Dagbladet’s famous pseudonyms, Bansai.

A young female journalist hides behind the mask of Bansai. Instead of enjoying a traditional holiday, she has applied for employment as a maid on a farm in Sörmland. She has thus passed a month there without anyone around her knowing that her presence is nothing more than a performance. For such a whim to strike a young lady may, at first glance, seem an instance of pure eccentricity. However, it has been steered by other motives that Svenska 35 Dagbladet wishes to briefly state here. Year after year, it was becoming increasingly difficult to acquire the required female workforce for farm labor. Why was this the case? The answer may be of utmost importance to our agriculture. The answer would also likely be best offered by whosoever was personally involved and sought to have their eyes opened to the surrounding influencing factors while under the weight of such toil. The author herself will give an account of her experiences below and in the following issues. Hence, we give her the floor and invite readers to an interesting and perhaps instructive study of how a farm girl lives.

-

- From Svenska Dagbladet, June 28, 1914.

The headline couldn’t be missed as it ran across four columns: A month as a maid on a farm in Sörmland. The article was illustrated with two pictures of Ester at work, wearing a headscarf and apron. One was staged on her return. The other had been borrowed from Anton Holtz, who still had no idea that the photo he’d sent along with his maid on her way back home had now been published in a national newspaper — a paper in which he would personally be described in detail in a series of articles throughout the summer.

Bansai’s articles transported readers from their wicker chairs, upholstered armchairs, and plush sofas to the Sörmland County farmhouse. They sensed the smells and the flavors, heard the language, felt how the yoke cut into their shoulders and how their hands ached. They went back and forth between laughing and sinking into somber reflection. The articles were personal and revealing, with a humorous edge. No journalist in the country had done anything like this before. Swedish investigative reporting was born.

Additional Resources

Join GIJN in Sweden for the Global Investigative Journalism Conference

GIJN’s Guide to Undercover Reporting

GIJN Bookshelf: Investigative Titles for Your 2022 Reading List

Fatima Bremmer is a journalist and author. She has worked as a reporter and editor-in-chief at the news department at Aftonbladet and Expressen and also at Svenska Dagbladet’s editorial department for culture. She is currently writing a biography about an infamous league of women who dared to challenge the rules of their time to win freedom for women.

Fatima Bremmer is a journalist and author. She has worked as a reporter and editor-in-chief at the news department at Aftonbladet and Expressen and also at Svenska Dagbladet’s editorial department for culture. She is currently writing a biography about an infamous league of women who dared to challenge the rules of their time to win freedom for women.