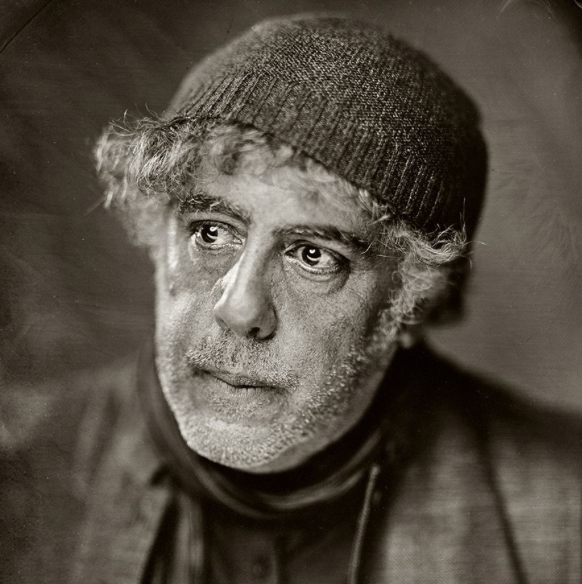

Bodies collected at various sites in Bucha, Ukraine, are brought to the cemetery for inventory as authorities investigate possible war crimes perpetrated by Russian forces in Ukraine, 2022. Image: Courtesy of Ron Haviv, VII

Editor’s Note: This is a chapter excerpt from GIJN’s Reporter’s Guide to Investigating War Crimes. The guide will be released in full this September at the Global Investigative Journalism Conference. The end of this chapter also features a special focus interview by Olivier Holmey with the editor-in-chief of the Crimean Center for Investigative Journalism, Valentyna Samar, whose site has extensively covered the 2014 and 2022 invasions of Ukraine by Russia.

On August 15, 2017, the International Criminal Court issued an arrest warrant for Mahmoud Mustafa Busayf Al-Werfalli, a commander of the Libya National Army’s Al-Saiqa Brigade, accusing him of having committed or ordered 33 murders between 2016 and 2017. Seven incidents captured in seven videos posted on social media accounts were key evidence for the Court to charge Al-Werfalli for murder as a war crime under Article 8(2)(c)(i) of the Rome Statute. Effectively, this arrest warrant was based upon open source information. While Al-Werfalli was never arrested nor saw the inside of a courtroom (he was shot dead in Benghazi by unidentified gunmen in 2021), this incident is seen as one of the first to acknowledge that open source information can be used as evidence for legal proceedings concerning violations of international humanitarian law or international crimes, namely, for war crimes, crimes against humanity, and genocide.

Of course, journalists had used open source research for years before this arrest warrant was issued. News organizations covered terrorist attacks in London in 2005 thanks in part to video filmed by eyewitnesses on London’s public transport system. This trend gathered pace in the early 2010s as Arab Spring protests in Tunisia and Egypt, and conflicts in Libya and Syria were filmed and shared on social media thanks to cheap camera sensors on mobile telephones and fast mobile internet connections. At the same time, the first commercial companies also launched satellites able to capture images of the Earth at less-than-one-meter (about 3.3 feet) resolution. As the cost to access these images fell, their use for newsrooms to analyze remote locations grew. News organizations started to collect content shared on social media networks and use it in their storytelling. When it became clear that this content also needed to be checked for authenticity, newsroom teams skilled in verification became important.

The 2019 book “Digital Witness,” by Sam Dubberley, Alexa Koenig, and Daragh Murray. Image: Courtesy of Oxford University Press

During the first years of the Syrian conflict, it became evident that open source information could not only be used to tell news stories, it could also play a role in investigating violations of international humanitarian law and possible war crimes. This wasn’t something new. As Alexa Koenig, Daragh Murray, and Sam Dubberley noted in their 2019 book “Digital Witness,” videos were played in the courtroom of the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia. Over the next decade, this investigative practice was codified by emerging standards and training practices, such as the Berkeley Protocol on Digital Open Source Investigations (last updated in 2022) by the United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR). Currently, newsrooms, human rights organizations, international fact-finding missions, and international legal mechanisms investigating violations of international humanitarian law and international crimes use open source information as a standard part of their work.

Pros and Cons of Open Source Research

Advantages

When it comes to investigating violations of international humanitarian law or international crimes, open source information can offer a very valuable method to establish facts when used together with other sources, such as site visits and interviews. Open source information can help establish facts with respect to a wide range of situations in the context of armed conflict. These range from investigations into attacks on civilians and civilian structures, the types of weapons used to carry out attacks, investigations into actions by perpetrators, or investigations into whether certain attacks against civilians are widespread or systematic — a key feature of international crimes against humanity.

With respect to all these dimensions, open source information is an important tool to establish a multitude of facts. In terms of attacks on civilians or civilian structures, for example, open source information gathered from multiple images, videos, and satellites can help establish the location and time of an event, numbers of people present at a location, whether civilian, military, or other actors were involved, and possible legitimate military targets or the size and scale of the observable outcomes of military operations on the ground. In cases of possible violations of international humanitarian law or unlawful killings and torture, the perpetrators themselves, or their associates, have been known to film and share videos of their acts on social media messaging apps. These, too, constitute open source information and may be important evidence not only for proving that an individual committed an act in violation of international humanitarian law, but also for proving the criminal intent of the perpetrators or their superiors necessary for demonstrating an international crime.

Military activities, in particular in urban areas, are frequently captured by mobile telephone cameras or are visible in satellite imagery — providing key information that can play a role in understanding what happened. Here, open source information can help answer the question: “Should this incident be investigated further as a potential violation of international humanitarian law, or does it appear to be a legitimate military attack?” If, for example, open source information is able to support the observation that the object of the attack was a military target due to the clearly identifiable military presence at a location, these immediate findings may weigh against deepening the investigation into one of a possible violation of international humanitarian law. These types of conclusions invariably, however, require consultations with international humanitarian law experts. If, based on the initial analysis, further investigation is warranted, open source information can also help come to a determination that an incident is an apparent violation or not.

Journalists can use open source information to look for a number of vital details, including:

- Military units and activity. Are uniformed military personnel visible in videos or photographs? Are uniforms, emblems, and equipment recognizable?

- Possible military targets. Once the location of the military operation is identified, open source information can be a useful guide to help identify if possible military targets were at or closely adjacent to the location of an attack. With the right skills, it is possible to identify military targets using mapping tools and high-resolution satellite imagery to check for military compounds or installations, as well as identify large military vehicles such as trucks, tanks, other armored vehicles, and aircraft.

- Civilian activity. Where has the attack taken place — in a residential neighborhood, an evacuation point, an apartment building, a hospital, or elsewhere? Are there civilians to be seen, such as children or older people? What are they doing? Can you count the number of civilians either dead or alive visible in the open source information?

- Weapons identification. Victims of attacks who have filmed the scene can often post images of the remnants of weapons or other military materiel online. These can include shrapnel from missiles or rockets, bullet casings, cluster submunitions, ordnance packaging, and so on. Identifying these weapons can help in an overall determination as to the proportionality of an attack and whether it was indiscriminate.

- Injuries and forensic pathology. Determining causes of death is notoriously difficult using open source information, and must be done carefully, and only by referring to experts in forensic pathology. While what these experts can ascertain from a video is limited, it can help, for example, identify signs of torture, or establish a range of possibilities for cause of death, or exclude other possibilities. Any analysis here, however, must be approached with caution and used, in the main, to corroborate other information that the journalist has at hand.

- The prior state of the attack site. Open source information can help determine if there was known civilian activity or information that military commanders should have been aware of prior to the military activity, or if the location was being used for a military purpose before the attack. For example, historical satellite imagery enabled journalists to identify the word “Дети” (“Children” in Ukrainian) painted outside the Drama Theater in Mariupol, Ukraine, in the days before an airstrike destroyed the building sheltering hundreds of civilians in March 2022. This attack has been decried by some international human rights groups as a likely war crime.

Russia’s bombing of a drama theater in Mariupol, Ukraine (seen here with red roof, two days before the attack), which was used to shelter children, prompted war crimes accusations from organizations like Amnesty International. Image: Screenshot, The Moscow Times

Drawbacks

Journalists should follow words of warning when using open source information to investigate violations of international humanitarian law or international crimes. Even though open source techniques are now seen as a compelling storytelling technique in their own right, researchers should avoid relying solely upon them and instead see these techniques as but one part of the larger investigative process. For open source information to play its role, journalists should collaborate with a broad range of actors, including, just to mention a few, on-site investigators, weapons experts, forensic pathologists, and lawyers.

Journalists must also recognize the limitations of open source investigations. For example, these techniques are of limited use in establishing what type of information military personnel had available to them at the time they decided to attack. Likewise, they’re of little to no help in understanding what type of military advantage was pursued with one or a series of targeting operations, which are necessary elements when proving the existence of certain types of international crimes.

In addition, reporters must consider the weighty legal or ethical reasons that may exist for not publishing open source information. The use of such information publicly may be outright banned by international humanitarian law (such as the use of images and videos that openly identify prisoners of war) or there may be concerns with respect to the freedom from inhuman or degrading treatment or the right to privacy of individuals who are recorded. Alongside this, ethical considerations could include risk to the captured individuals whose likenesses are uploaded or depicted in the open source information if the content is amplified by a news organization. Journalists should also remember that, even in an armed conflict, copyright considerations may apply if the content is to be used in reporting.

Aside from these limitations on open source information in general, there are also technical limitations.

Image quality. Photographs and video shared to social media have been compressed from their original quality. This means, for instance, it may be difficult if not impossible to verify logos or letterings on uniforms of a military unit, or to distinguish between weapons and, say, farm tools.

False analysis. Geospatial analysis is an area of open source research that requires training to conduct the analysis properly. It is also an area where a little bit of knowledge can lead to false conclusions. It is, therefore, important that investigators understand the limitations of what is visible in a satellite image and be able to analyze what they see correctly. For example, it is important for journalists to understand that disturbed Earth seen from space does not automatically equate to evidence of a mass grave. Earth can be moved for many reasons, and craters can be created by other incidents prior to an alleged attack.

Using satellite imagery from Planet Inc., GIJN member Texty identified masses of train cars (red), trucks (blue), and freight ships (green), possibly smuggling stolen grain out of Ukraine by Russia. Image: Screenshot, Texty via Planet Inc.

Tips and Tools

Mindset Is Bigger than Toolset

While below we outline tips and tools for using open source platforms for investigations, one of the biggest challenges of using open source information is that the tools and methods for searching and verifying can change very quickly. This is predominantly because a lot of the tools are free, and are provided by the social media platforms themselves. More important, therefore, than relying on the tools is having the mindset of an open source investigator. That means being creative in finding solutions and constantly learning and thinking about new ways of doing research or gleaning information. Without this mindset, the skills of the open source researcher will grow stale quickly.

Searching for Content

Each social media platform is popular in different parts of the world. Therefore, a key first step is to understand what kinds of open source information are likely to be shared and how the search functions of the local preferred platforms work. For instance, in the Ukraine conflict, Telegram has been by far the most important platform on which one can discover text, videos, and photographs posted by witnesses, military personnel, and government officials. Relevant information on that war as well as individual incidents can be found using a combination of English, Ukrainian, and Russian keywords. Cities and towns across Ukraine have established Telegram channels that act as aggregators where local residents post content to be shared. (Note: Some of these local channels also have been flagged as bots or potential Russian disinformation sites.) By identifying these aggregator channels, journalists have been able to collect and verify large amounts of videos and photographs showing killed or injured civilians, destroyed civilian infrastructure, and remnants of munitions.

Collecting Content

Considering the volume of photographs and videos now posted to social media from conflicts across the world, ensuring a robust way of collecting and analyzing information is critical. Failure to do this can very quickly lead to feelings of confusion or being overwhelmed. While there are content management systems designed for open source investigations, such as Truly Media by Deutsche Welle or Uwazi by HuriDocs, a lot can be done by a well-designed spreadsheet. These allow the researcher to more easily sort the data and perform analysis on individual items, which can allow determinations to be made about weapons, patterns of violations, and so on.

Archiving Material

Videos and photos depicting war crimes are often, by their nature, violent, disturbing, or distressing. So, it is no surprise that these can quickly disappear from the platforms on which they were posted for a variety of reasons. (Most social media networks’ terms of service prohibit sharing of violent or disturbing content, which means offending posts are often removed by the platform itself.) It is therefore essential that content is preserved promptly when researching incidents. Tools such as the Internet Archive or archive.today are good for preserving photographs or text posted to websites, and have the advantage that they are then saved for other researchers as well. Videos, however, currently require the researcher to take preservation into their own hands. Those who feel comfortable with Terminal command-line interfaces can use an open source tool named youtube-DL to preserve video. If an organization is using a lot of open source video, it might be a worthwhile investment to build a user interface for YouTube-DL that preserves content on the organization’s own servers for security reasons. (Note: YouTube-DL has faced shutdown issues in the past due to alleged copyright complaints, and recently a German court ruled that its website host could be liable for content rights violations.)

Verification of Open Source Information

The failure to verify open source content comes with a very high risk — and is not recommended. That risk grows even higher when making claims about the most serious of charges, such as violations of international humanitarian law or war crimes. Much has been written elsewhere about the processes of reverse image search, checking metadata, geolocation, and chronolocation, which are all key for the verification process and apply here. But investigating the activities of warring parties needs further verification steps. For example, if geolocated, user-generated tools that map military installations such as Open Street Map or Wikimapia can help identify if a documented attack that led to civilian casualties was close to a legitimate military target. Camopedia describes itself as a database of “major military and paramilitary camouflage patterns that have been in use around the world since the beginning of the 20th century” and is essential to verify if military uniforms seen in a piece of open source information are consistent with the military of the country they are supposed to represent.

Case Studies

Russian Airstrikes on Syrian Civilians

This 2019 New York Times investigation used open source information, including video analysis, drone imagery, and cockpit radio recordings, to reportedly show that Russian Air Force fighter pilots were responsible for airstrikes that unlawfully killed civilians in a camp for displaced Syrian families in 2019. The team at The Times spent months deciphering the cockpit recordings of pilots allegedly involved in the attack.

The abandoned, debris-strewn streets of Aleppo, Syria, 2013. Aleppo, Syria’s largest city, endured some of the heaviest fighting between members of the Free Syrian Army, or FSA, and forces loyal to President Bashar al-Assad. Image: Courtesy of Franco Pagetti, VII

Cluster Munitions Attack in Ukraine

Human Rights Watch and the New York City-based visual investigations agency SITU Research meticulously recreated a cluster munition attack on a train station in Kramatorsk, eastern Ukraine, in April 2022. Their report debunked claims by the Russian Ministry of Defence that its armed forces had not deployed the weapon onto the Ukraine battlefield. Open source information and geospatial analysis was coupled with on-site research to provide compelling evidence that the station was a known civilian evacuation hub, that Russian forces had deployed the weapon, and that the cluster munitions had brought harm to civilians.

Execution of Tigray Men

Demonstrating the strength of collaboration in open source investigations, CNN International and Amnesty International worked together to verify five videos reportedly showing Ethiopian government forces executing several dozen men on a cliff near a small town in Tigray Province, in early 2021. Key to the open source element of this investigation was the use of 3D modeling and geolocation of where the massacre took place.

Special Focus: Covering Russia’s Invasion of Ukraine

Interview of Valentyna Samar, by Olivier Holmey

Before Russia’s annexation of Crimea in early 2014, the Information Press Center (IPC) and the Crimean Center for Investigative Journalism (CIJ) leveraged an extensive network of branches on the peninsula – in Yalta, Sevastopol, Yevpatoria, Feodosia, Dzhankoi, and Simferopol – to investigate corruption, despite the pressures of then-Ukrainian President Viktor Yanukovych.

Valentyna Samar, editor-in-chief of the Crimean Center for Investigative Journalism. Image: Screenshot, National Union of Journalists of Ukraine

On March 1 of that year, men in fatigues bearing the Russian flag forced their way into the IPC and CIJ’s joint headquarters. “The activities of media centers in all cities, except Simferopol, were stopped,” recalls CIJ editor-in-chief Valentyna Samar. “Journalists were threatened with physical reprisals by paramilitary formations controlled by the Russian special services.”

By the end of the year, most of the media team had relocated to Kyiv. CIJ continued to cover Crimea in depth – from afar. From that experience, Samar says she learned to assess risks and look for opportunities to minimize them on a daily basis, if not several times a day. “Yesterday’s decisions may be wrong today,” she tells GIJN.

Open source tools proved essential to her team’s investigations, she says, as did working with Russian sources and with sources living in the occupied territories. Those years of remote coverage also taught her to part ways with those who disregard safety rules and professional standards. “‘One more chance’ for an irresponsible person can ruin the whole team,” she warns.

Following Russia’s large-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, almost all Ukrainian investigative media outlets began to work as CIJ had done during the previous eight years of the Crimea occupation.

“Many methods of investigation have come in handy in the new conditions of armed conflict,” Samar says. “For example, our skills in maritime open source investigations of violations of the sanctions ban by ships in Crimean ports were very suitable for investigating the “grain express” – the export of Ukrainian grain looted by Russia.”

CIJ makes sure that editors in Kyiv have access to the communication accounts of on-the-ground reporters, in order to delete their contents remotely in case of danger. Reporters even file reports in the “drafts” folder of shared email accounts, so that the reports can be accessed and deleted by editors without ever being emailed.

As for those who wish to cover Russia’s war on Ukraine, Samar first recommends learning the law and basic terminology of war crimes. “It is impossible to write professionally about war without basic knowledge of the laws and customs of war,” she says.

Additional Resources

Reporter’s Guide to Investigating War Crimes: Collecting and Archiving Evidence

Reporter’s Guide to Investigating War Crimes: Open Source Research

Reporter’s Guide to Investigating War Crimes: Attacks on Civilians

Sam Dubberley is the managing director of the Digital Investigations Lab at Human Rights Watch. Prior to joining HRW, Sam was the head of the Evidence Lab at Amnesty International where he conducted and led on a wide range of open source research for Amnesty International, including investigative collaborations with several media organizations, including CNN and NHK. Sam is a fellow of the Human Rights Centre at the University of Essex and has been a fellow of the Tow Center for Digital Journalism at Columbia University. He is the co-editor of the book ‘Digital Witness: Using Open Source Information for Human Rights Investigation, Documentation, and Accountability’ published by Oxford University Press in 2020.

Sam Dubberley is the managing director of the Digital Investigations Lab at Human Rights Watch. Prior to joining HRW, Sam was the head of the Evidence Lab at Amnesty International where he conducted and led on a wide range of open source research for Amnesty International, including investigative collaborations with several media organizations, including CNN and NHK. Sam is a fellow of the Human Rights Centre at the University of Essex and has been a fellow of the Tow Center for Digital Journalism at Columbia University. He is the co-editor of the book ‘Digital Witness: Using Open Source Information for Human Rights Investigation, Documentation, and Accountability’ published by Oxford University Press in 2020.

Başak Çalı is Professor of International Law at the Hertie School and Co-Director of the School’s Centre for Fundamental Rights. She is an expert in international law and institutions, international human rights law and policy. She has authored publications on theories of international law, the relationship between international law and domestic law, standards of review in international law, interpretation of human rights law, legitimacy of human rights courts and implementation of human rights judgments. She is the Chair of European Implementation Network and a Fellow of the Human Rights Centre of the University of Essex. She has acted as a Council of Europe expert on the European Convention on Human Rights since 2002. She has extensive experience in training members of the judiciary and lawyers across Europe in the field of human rights law. She received her PhD in International Law from the University of Essex in 2003.

Başak Çalı is Professor of International Law at the Hertie School and Co-Director of the School’s Centre for Fundamental Rights. She is an expert in international law and institutions, international human rights law and policy. She has authored publications on theories of international law, the relationship between international law and domestic law, standards of review in international law, interpretation of human rights law, legitimacy of human rights courts and implementation of human rights judgments. She is the Chair of European Implementation Network and a Fellow of the Human Rights Centre of the University of Essex. She has acted as a Council of Europe expert on the European Convention on Human Rights since 2002. She has extensive experience in training members of the judiciary and lawyers across Europe in the field of human rights law. She received her PhD in International Law from the University of Essex in 2003.

Ron Haviv is a director and co-founder of The VII Foundation and co-founder of VII Photo Agency. In the last three decades, Haviv has covered more than twenty-five conflicts and worked in over one hundred countries. His work, which has won numerous awards, is featured in museums and galleries worldwide.

Ron Haviv is a director and co-founder of The VII Foundation and co-founder of VII Photo Agency. In the last three decades, Haviv has covered more than twenty-five conflicts and worked in over one hundred countries. His work, which has won numerous awards, is featured in museums and galleries worldwide.