The media environment has become increasingly hostile in Nicaragua, and many journalists are now forced to report from exile. Image: Shutterstock

The award-winning Nicaraguan journalist Carlos F. Chamorro delivered the annual Reuters Memorial Lecture in Oxford earlier this month. Chamorro is the editor of the news site Confidencial and hosts several TV shows. You can watch the lecture, and read the original post on the site of the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism.

On February 15 of this year, 94 Nicaraguan citizens were stripped of our nationality by the regime of Daniel Ortega and his wife Rosario Murillo. It was an illegal and unconstitutional act, in violation of international treaties signed by Nicaragua. The penalty also included the loss of our political rights in perpetuity and the confiscation of our properties and assets, including our Social Security retirement pensions.

The list of 94 includes 11 journalists, directors such as myself of exiled media outlets like Confidencial, 100% Noticias, Artículo 66, Nicaragua Investiga, Radio Darío, Divergentes, Café con Voz, and others.

Six days earlier, on February 9, another 222 people, all political prisoners, were released from prison, deported to the United States, and also stripped of their Nicaraguan nationality. With this act of revenge, Ortega erased with one hand the gesture he made with the other.

The only political prisoner who refused to accept the forced exile was Catholic Church Bishop Rolando Álvarez, who was sentenced a day later in a speedy trial to 26 years in prison. He has been transferred to a maximum security cell.

Among those released from prison were 12 people linked to the media: a sports reporter and blogger, three executives of the daily newspaper La Prensa, the journalist who founded the cable television channel 100% Noticias, a political television commentator, several local journalists, and even a driver for La Prensa, whose crime was having transported the reporters who covered the news of the expulsion from Nicaragua of the nuns of Mother Teresa of Calcutta’s order on July 6, 2022.

All of them had been convicted without any evidence for alleged crimes of “conspiracy against national sovereignty,” “money laundering,” and “spreading fake news,” and were held in isolation in prison or under house arrest for up to 600 days. Among the 327 people stripped of our nationality are political and civic leaders, economists, political analysts, attorneys, businesspeople, diplomats, academics, scientists, doctors, priests, and social activists.

Many of them have been essential sources of information for the independent press in a country where for more than 15 years, access to public records has been prohibited. As a result of the persecution, there are no longer any independent sources in Nicaragua to whom facts, data, or analysis can be attributed. Because of fears of official reprisals — including imprisonment — all of them, without exception, request anonymity as a condition to inform or give their opinion to the press.

This double-sided criminalization of both freedom of the press and freedom of expression with the purpose of silencing journalists, news sources, and freedom of opinion, represents the latest stage in a long process of demolishing the rule of law in Nicaragua.

Under the de facto police state, there is no freedom of assembly or association in Nicaragua. The regime persecutes the Catholic Church and even prohibits religious processions. In 2021, it got rid of all political competition and erased the possibility of holding free elections, and since 2022 it has increased its relentless persecution against civil society, shutting down more than 3,100 non-governmental organizations.

In this context, journalism done from exile remains the last reserve of all of our constitutional freedoms. Let me briefly explain where we have come from and how we got to this point.

Collapse of the Democratic Transition

Carlos F. Chamorro delivering the Reuters Memorial Lecture. Image: John Cairns, Courtesy of Reuters Institute

I began my journalism career under the dictatorship of Anastasio Somoza Debayle 45 years ago, in February 1978, one month after the assassination of my father, journalist Pedro Joaquín Chamorro, director of the newspaper La Prensa.

At that time, 20 years before the invention of the internet, journalists defied censorship of radio newscasts, reading the news in the atriums of churches in what was baptized as “catacomb journalism.” And in the final days of the insurrection against the dictatorship, Somoza ordered the destruction of the newspaper La Prensa, launching a tank attack against its installations, as if it was a military target.

During the Sandinista revolution, facing a war of foreign aggression and the civil war in the 1980s, the militarization of politics replaced journalism with war propaganda and counter-propaganda, imposing state censorship and self-censorship as norms.

In 1990, a democratic transition began in which the media flourished, in a true springtime for freedom of expression. Under the government of my mother, Violeta Barrios de Chamorro, freedom of the press and tolerance towards freedom of expression became government policy, along with the professionalization of the army and the police.

Mistakenly, we thought that democracy and the achievements of the transition were irreversible. But since Daniel Ortega’s electoral return to power in 2007, democratic institutions have been demolished in more than 16 years of authoritarian regression.

Combining electoral fraud and the illegal reelection of the president, Ortega was able to consummate the co-optation of all branches of government. Ortega’s wife, Rosario Murillo, who is the official spokesperson of the government, designed a communication strategy to impose so-called “uncontaminated information,” that is, information in what she called a “pure state” that would reach the citizens directly through the official media, without passing through the filters of questions or investigations by an independent press.

A decade before the emergence of Donald Trump in the US and Jair Bolsonaro in Brazil, Daniel Ortega had already labeled the independent press as “the enemy” and long before the era of “fake news” he accused journalists of being the “children of Goebbels,” unleashing virulent lynching campaigns in the official media in response to allegations of corruption and abuses of power by his government.

In the early years, Ortega promoted intimidation against the independent press, as well as political espionage and the blocking of access to public records. He also created his own private media empire. However, during the time he governed based on an economic alliance with big business without democracy or transparency, he tolerated the existence of media such as Confidencial that investigated the corruption of the regime, such as the diversion of more than five billion dollars of Venezuelan aid to his private businesses, or the mega-swindle of the failed interoceanic canal project. Probably because he had total control over all branches of the government — including the army and the police — he did not consider the weak political opposition to be either competition or a threat to his control.

Journalism Under a Totalitarian Dictatorship

When this model of authoritarian government collapsed under the explosion of civic protests in April 2018, the regime saw its power threatened, and it responded with brutal repression that left more than 300 murders in impunity. The press was also deemed an enemy to be crushed.

Repression against journalism included assassinations and physical assaults against journalists, television censorship, physical destruction of media outlets, and customs blockades to prevent newspapers from getting paper and other materials. All this culminated in the closure and confiscation of media outlets, the imposition of new repressive laws, and the imprisonment of journalists.

In the almost five years of socio-political crisis between 2018 and 2023, between de facto and judicial attacks, Nicaragua has concentrated all the crimes against the press that took more than a decade to carry out in Venezuela.

In 2020, the Special Law on Cyber Crimes was approved. This punishes with prison sentences of one to five years the alleged crime of spreading so-called “fake news” through social media and media outlets, which, according to the law, causes anxiety, destabilization, and moral damage. The law does not define what “fake news” is.

Under this law, more than 20 people have been sentenced to prison terms for the alleged crime of “fake news,” including journalists, activists, priests, and even a peasant who did not have any social media accounts.

Doing journalism under a dictatorship — to continue reporting and telling the truth — is an act of resistance. My own newsroom at Confidencial has been seized twice. First, our offices were raided by the police, without any warrant, at midnight on December 13, 2018, and then continued to be permanently occupied by armed guards. In November 2019, we set up a new temporary newsroom, but on May 20, 2021, we were again raided by the police, who once again stole all our computers and TV equipment. Despite all that, we never stopped reporting and broadcasting, not even a single day, by using digital platforms.

Ortega also seized the offices of the cable TV channel 100% Noticias and the newspaper La Prensa. But he has never been able to seize journalism itself, and the seized media continue to report from exile.

The regime has also shut down more than 40 local radio and television stations, and more than 150 journalists have been forced into exile. Some of them have reorganized around some 25 digital media outlets, mainly in Costa Rica, Spain, and the US. However, more than a third of exiled journalists have had to take on other jobs to survive, or have left the profession for fear of reprisals against their families.

Our television programs Esta Semana (This Week) and Esta Noche (Tonight) have been banned from broadcast and cable television, but we continue to reach an audience of more than 415,000 subscribers through Confidencial’s YouTube channel and Facebook.

Social media represents an extraordinary vehicle for overcoming censorship, but it has also become a space for disinformation and political polarisation that competes against the independent press. Without democracy and the rule of law, the existence of a free press is threatened by the arbitrariness of power without limits, as is the case today in Nicaragua, Cuba, and Venezuela, where there is no protection for journalists.

Human rights organizations and organizations that work for freedom of the press in the Americas and Europe have made an extraordinary effort to document and make visible the persecution of the press in these three countries.

But ultimately, our only protection lies in doing more and better journalism to strengthen the credibility of the media and our relationship with our audiences. Only quality journalism can determine the effectiveness of the press against the machinery of disinformation and propaganda of the five television stations, dozens of radio stations and internet portals which are managed by the ruling family as private businesses paid for by the state.

Lessons from Nicaraguan Journalism in Exile and Beyond

Since mid-2021, I have been in exile in Costa Rica for the second time to avoid being silenced because of a criminal indictment and arrest warrant for me in Nicaragua. My entire newsroom, and practically all independent media, are working from exile.

Exile is no longer a temporary emergency situation that forces us to leave and relocate to another country. It’s now a permanent, medium-term condition that poses immense challenges for journalism. Our purpose continues to be to tell the story of how to change a dictatorship through civic resistance, but this news is not to be reported in the exile bubble in Costa Rica or the US but in Nicaragua.

Reporting on Nicaragua from outside the country requires cultivating sources that are actively at risk under the police state. At the same time, it means raising the standards of verification and corroborating anonymous sources in order to continue publishing reliable information.

Second, we must develop our sources’ trust in order to investigate corruption, government employees’ discontent, and the crisis of the regime from within. We also have to guarantee secure channels of communication to protect our sources.

Third, we have to expand our capacity for observation and reporting through a network of collaborators, and we professionally curate the torrent of images and information on social media to be able to see, hear, and report on the mood of daily life, the social crisis, repression, resistance, and hope for change.

Fourth, we face the challenge of continuing to innovate in digital platforms in order to strengthen our relationship with our audiences and to tell memorable stories that allow us to counteract official lies and viral misinformation on social media.

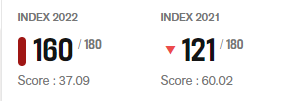

Nicaragua has plunged down the rankings in the annual Press Freedom Index, dropping nearly 40 places in one year. Image: Screenshot, Reporters Without Borders

Fact-checking initiatives are necessary but not sufficient means to overcome misinformation. In addition, it’s necessary to recover the credibility and trust in a useful press, capable of reconnecting with its audiences, and even of taking advantage of the reach of social media to promote quality journalism.

Fifth, journalism in exile also is involved in international and Latin American collaborative journalism initiatives, such as the Latin American Center for Investigative Journalism (CLIP) or the Journalistic Platform for the Americas (CONNECTAS), to produce regional stories that unfold in several countries that we tell through innovative multimedia narrative formats.

And last but not least, we face the challenge of the financial sustainability of journalism in exile. In addition to the crisis caused by the digital revolution and unfair competition with technological giants, we face the criminalization of our traditional advertisers. The crisis forces us to look for new models of economic management to finance the independence of our media through international donations, audience contributions, and commercial monetization.

But this also demands a paradigm shift for philanthropic foundations and international aid agencies that support independent journalism. It becomes necessary to recognize that the survival of the press in exile, not only in Nicaragua, Cuba, and Venezuela, but also in Russia, Ukraine, Iran, Afghanistan, Myanmar, Azerbaijan, and other countries as a democratic imperative that requires long-term support strategies.

Investigating Repression

I have selected a sample of 10 stories, published in Confidencial between 2018 and 2023, some of them international award winners, that best illustrate how we are reporting under a dictatorship.

- The investigation They Shot to Kill with Precision was published in Confidencial in June 2018. Based on nineteen CT scans of victims killed and wounded during the repression, it revealed the existence of a lethal pattern of shots to the head and thorax of civilians, carried out by snipers with weapons of war. The evidence, corroborated by medical specialists and by the testimonies of the victims’ family members, became one of the pillars supporting the subsequent reports of the international human rights commissions on the massacre and the so-called “clean-up operation” in Nicaragua.

- This in-depth interview with economist Ligia Gómez, former political secretary of the Central Bank, was published in November 2018. It was about the moment when the government issued the order “Vamos con todo” (“Let’s go all out”) to unleash the massacre, and was the first in a series of investigations into how the chain of command of repression functions as a coordinated operation between police and paramilitary groups.

- The series of investigations, published in February 2020, on Extrajudicial Executions in the Countryside and the Massacre of Peasants revealed a hidden reality in rural areas, with more than 30 murders that occurred between 2018 and 2019, and the co-responsibility of the Nicaraguan Army.

- Investigations on governmental concealment of the tragedy of the massive numbers of deaths caused by COVID-19, published in 2021 and 2022, showed that Nicaragua was one of the countries with the highest rates in the world of excess mortality due to COVID-19, based on a comparative analysis, during the first 21 months of the pandemic, of the official death certificates for pneumonia, heart attack, diabetes, and hypertension. This was a data journalism story with a human face, thanks to the testimonies of the victims’ family members and of the doctors and health workers who defied official censorship, many of whom paid the cost of dismissal and repression.

- Reports on the conditions of hundreds of political prisoners subjected to prolonged torture and isolation as well as investigations on the impunity of the police, the Prosecutor’s Office, and the judiciary have dominated the news between 2018 and 2023. All the while, the regime failed in its effort to erase political prisoners from the national memory.

- The investigation into the Ortega-Murillo family’s network of 22 private companies, published in February 2022 and based on official board minutes, revealed the existence of a network of frontmen and a system of corruption in their private businesses that are financed by public funds and the diversion of Venezuelan government aid.

- The identity-protected testimonies of senior government officials and dozens of public servants on corruption and repression, published in 2022, revealed the increasing erosion of political support for the regime which has turned government workers into hostages.

- Between 2018 and 2023, there has been a mass exodus of more than 600,000 Nicaraguans, mainly to the US and Costa Rica, equivalent to 10% of the total population. Confidencial’s Nicas Migrantes platform has told the story of the other Nicaragua: migrants stranded in Ciudad Juarez, Mexico, those who have drowned trying to cross the Rio Bravo or perished suffocated in a van in Mexico abandoned by coyotes, and migrant workers who are victims of labor exploitation in Costa Rica.

- The investigations on the Ortega regime’s main international allies — Russia, Cuba, Venezuela, China, and Iran — have revealed clientelistic relationships with governments that promote political espionage and impunity and that have had little or no positive impact in terms of investment, international trade or foreign aid received by Nicaragua.

- The cartoons by PX Molina, and the political satire of the television segments La Ultima Mirada News (The Last Look News) and Fuera de Broma (Joking Aside) have demonstrated that humor and mockery represent the most effective resource in the face of authoritarian power as a way to dismantle the Orwellian language of official lies.

None of these journalistic investigations produced any change in the public policies of Daniel Ortega’s authoritarian regime, which is not designed to be held accountable. However, many of these stories and these data are valuable inputs for the report on human rights violations in Nicaragua presented today in Geneva by the Group of Experts at the UN Human Rights Council meeting. The report concludes that there is clear evidence of the responsibility of President Daniel Ortega, Vice President Rosario Murillo, and the chain of command of the State in the commission of crimes against humanity that continue to this day in Nicaragua.

The evidence of this significant report is the imprint of Nicaraguan journalism in exile. Together with the families of the victims of the repression, journalists have documented the first draft of truth and memory to lay the foundations of justice as one of the pillars for the restitution of democracy in Nicaragua. Meanwhile, the state maintains the hate speech it uses to stigmatize citizens as “coup perpetrators,” “terrorists,” and now “stateless.” But despite the fear and silence — and the attempt to normalize a dictatorship in impunity — the independent press is winning the battle for the truth.

The main challenge for the press in the face of the deterioration of democracy will always be to monitor power and do good journalism, even in the midst of the worst conditions of political polarization.

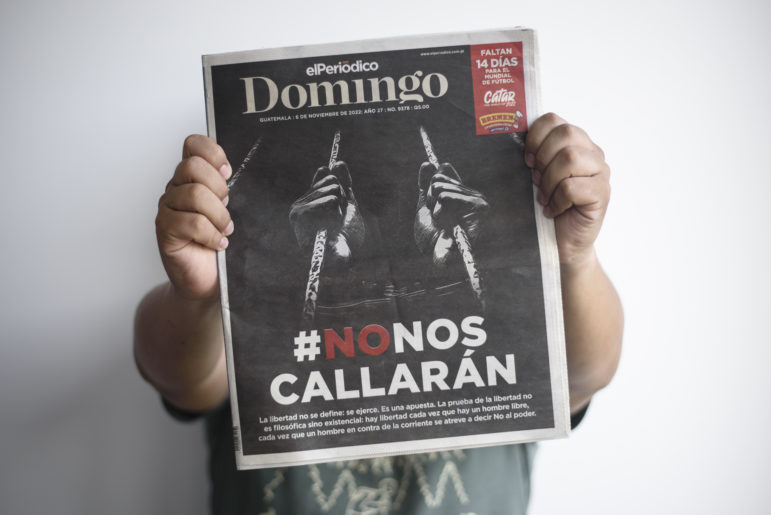

The collapse of the rule of law in Nicaragua and the consolidation of the dictatorship is a mirror in which the Central American press, threatened by authoritarian tendencies, is reflected today. In Guatemala, the Giammattei government has kept José Rubén Zamora, editor of El Periódico, in jail for seven months. In El Salvador, the Nayib Bukele regime has already tagged the independent press as “the enemy.” In Honduras, we celebrate the Gabriel Garcia Marquez award that was conferred by the Gabo Foundation to young journalist Jennifer Avila, director of Contracorriente, as an example of courage and practicing good journalism in the context of violence, corruption, and organized crime.

In Guatemala, Ramón Zamora, son of detained journalist José Rubén Zamora, holds one of the last printed editions of elPeriódico. The cover reads “We won’t be silenced.” Image: Raúl F. Pérez Lira

Central American journalists are united by our commitment to not give in to intimidation and censorship, nor to fall into self-censorship. As proclaimed by the new Central American Network of Journalists, created last year in Guatemala: “Silence is not an option.”

And in the face of the temptation that journalists sometimes suffer to supplant the role of political parties and other institutions in crisis, we have to remember every day that journalists are not judges, detectives, police, or auditors. Our mission is also not to stray into activism but to preserve our autonomy to monitor public and private powers and the new forces that advocate change.

Nicaragua’s experience shows that the resistance of the press in exile under a dictatorship is not enough to clear the way for democratic change, but as long as it continues to do more and better journalism, it will keep the flame of the freedom of the press burning as the last reservoir of all freedoms.

Additional Resources

In a Hostile Climate, Guatemala’s Journalists Fear the Law Being Turned Against Them

Forced Out: Latin America’s Investigative Reporters Pushed into Exile