Table of Contents | Introduction | Chapter 1 | Chapter 2 | Chapter 3 | Chapter 4 | Chapter 5 | Chapter 6 | Chapter 7 | Chapter 8

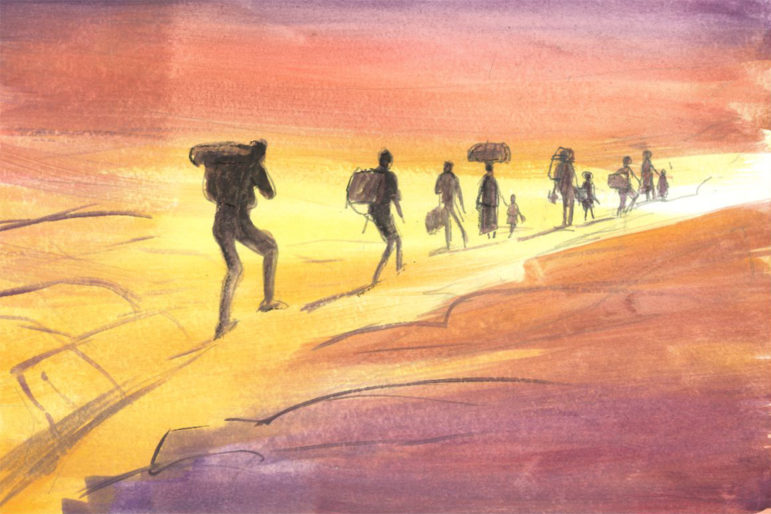

Illustration: Dominique Mwankumi for GIJN

The list of organized crimes tearing Africa apart is much longer than the chapters of this guide. Behind the horrific images of thousands of people perishing in the Mediterranean Sea, the deadliest migration route in the world, we must acknowledge, among other things, the action of criminal groups. Behind the drama of African girls and women forced into sexual or domestic slavery, there is no need to go far to find the hand of crime gangs. Do you know of the brouteurs (grazers)? These notorious networks of cybercriminals scour the cybercafés of some African cities, sowing human tragedy on the other side of the line. Do you really think that drug trafficking is the only lucrative business that attracts the attention of criminal groups? What would you say about cigarette smuggling, counterfeit goods, and antiquities theft? In this chapter, we will provide a brief survey of some of these other crimes and how to investigate them.

Human Trafficking and Migrant Smuggling

The International Organization for Migration (IOM) defines migrant smuggling as “the procurement, in order to obtain, directly or indirectly, a financial or other material benefit, of the irregular entry of a person into a State Party of which the person is not a national or a permanent resident.”

Human smuggling is often an element of other, broader misconduct involving trafficking in persons or human trafficking. The IOM notes they often involve other types of additional crimes such as, “the prostitution of others or other forms of sexual exploitation, forced labor or services, slavery or practices similar to slavery, servitude or the removal of organs.”

From sex workers to domestic helpers, from refugees to footballers, thousands of Africans are caught in traffickers’ nets every year. One common example of human trafficking revolves around the illicit smuggling networks that demand exorbitant fees to help African migrants cross the Mediterranean into Europe. Another tragic case: African migrants being sold into modern slavery in Libya, as uncovered by a 2017 CNN investigation that sparked international outrage.

To better understand migration-related terminology, this glossary from the IOM can help.

African migrants aboard an Italian Coast Guard vessel. They were part of a larger group who were trying to cross the Mediterranean Sea and who were intercepted 90 miles south of Sicily. Image: Shutterstock

Tips and Tools

Pulitzer Prize-winning reporter Maggie Michael, who has covered human trafficking in North Africa and the Middle East, suggests starting from the following sources:

- Anti-trafficking agencies in the countries of origin and destination. For instance, the Nigerian National Agency for the Prohibition of Trafficking in Persons, the Gambian National Agency Against Trafficking In Persons, or the United Arab Emirates’ National Committee to Combat Human Trafficking.

- Court cases involving trafficking, which can help the reporter get ideas on who is implicated in the trafficking in their countries and their allies, how they work, who was convicted, former victims, etc.

- NGOs focused on assisting trafficking victims may also help get testimonies for journalists to understand the patterns of human trafficking and migrant smuggling. Some of these agencies include Yocht in Yemen, Horizon Sans Frontières in Senegal, Association Iroko Onlus in Italy, and Do Bold, based in The Netherlands.

- Researchers who might have had a chance to get in touch with former traffickers, like those at the African Center for Study and Research on Migration or the Senegalese university-based Migration Studies and Research Group.

- From the local ministries of labor, find lists of recruitment companies (licensed in both the destination and origination countries) and find the stakeholders to determine if there are politicians or other powerful people behind them. Were any of these companies suspended or sanctioned, and if so, why? Look for the partners of the company in the country of destination and what has happened to the workers.

- Social media can help reveal their recruitment techniques. Interview people interacting with the recruitment companies. Use LinkedIn to identify former officials in these recruitment companies. See GIJN’s resources on how to mine social media.

Monitor the Latest Trends and News

Various global NGOs and government agencies monitor the field closely. They are useful for finding relevant data, reports, and sources.

- Minderoo (Walk Free) Foundation, Polaris Project, International Justice Mission, Free the Slaves, and Catholic Charities are NGOs that follow developments closely. They may have in-country representatives who can offer assistance in a particular region.

- Global Slavery Index gives an overview on the latest patterns of trafficking around the world latest patterns and numbers of migration.

- The UN’s International Organization for Migration “conducts and supports data production and research” related to migration policy and practice across the world.

- Mixed Migration Centre is a rich source of studies and reports because it has monitors on the ground who report on the movement of people.

- To look into how money laundering and terrorist financing risks arise from migrant smuggling, here is a 2022 report from the inter-governmental body Financial Action Task Force (FATF) that can help.

Follow Other Journalists’ Work

Follow specialized media, such as GIJN member The New Humanitarian, as well as the EU-funded platform InfoMigrants, which is a collaboration led by three major European media sources. Another good source is Enass, an online news site that intensively covers migration issues, putting the spotlight on the fate of sub-Saharan migrants transiting through Morocco on their way to Europe.

Going Undercover

Journalists in Africa have used undercover techniques to do groundbreaking investigations on human trafficking. Due to the number of people that traffickers aim to attract into their business, this offers the opportunity to set up a clever undercover exposé, which can provide high-impact camera scenes and first-hand evidence. See, for example, this series by a Ugandan New Vision reporter, who was trafficked and sold in the UAE and later put on a sale market in Saudi Arabia, before being deported on suspicion of espionage. Or this BBC Africa Eye piece that tells the dark trade of African women lured into India for sexual slavery. Or this chilling documentary (see video below) that shows disabled children being trafficked from Nairobi to Tanzania to beg for money on the streets while held in captivity by slave masters. (Note: undercover reporting presents many ethical and security risks, so to learn more about best practices, consult GIJN’s Guide to Undercover Reporting.)

Hold Aid Institutions to Account

International institutions like the EU grant aid to African countries — among them Senegal, Niger, and Libya — in an attempt to slow down the flow of migrants to Europe. But there is often little oversight on spending, and the aid may never reach those who need it. Consult this list of African countries and agencies that receive such aid from the EU.

Similarly, check the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs’ financial tracker to find out which NGOs receive aid from the EU and the US Agency for International Development — and how they spend it. Examine these projects on the ground to see if the money they receive is well spent.

In an effort to stop migrant flows, destination countries often violate immigrants’ rights. Illegal pushbacks have become a standard practice. See, for example, this exposé by a cross-border consortium holding the European EU border agency Frontex to account, or this investigation by Enass of an incident at the Spanish enclave of Melilla bordering Morocco, which left dozens of migrants dead.

Cybercrime

Cybercrime is defined by the UN Office of Drugs and Crime as an illegal act “perpetrated using information and communication technology (ICT) to either target networks, systems, data, websites and/or technology or facilitates a crime.” According to the UN Economic Commission for Africa, cybercrime is “one of the top risk factors likely to jeopardize Africa’s economy.” Kenyan IT cybersecurity company Serianu estimates that “cybercrime reduced GDP within Africa by more than 10%, at a cost of an estimated US$4.12 billion in 2021.” Similarly, the French daily Le Monde reports that Africa today is threatened by “digital chaos.”

Based on input from member countries in Africa, Interpol identified five major cyber threats in Africa: online scams (considered the highest-reported and most pressing cyberthreat across the region), digital extortion, compromised business email, ransomware, and botnets (networks of compromised machines used for large scale campaigns such as DDoS attacks, phishing, and malware).

Start with Victims and Police Records

Journalists from Radio-Canada, in collaboration with colleagues from Côte d’Ivoire, investigated an online love scam that originated in the West African country and left a dozen victims in Canada. As a member of the team that conducted the 2021 investigation, Michael Deetjens shared with GIJN some tips for digging into other online scams.

“We started our research from raw data provided by the families of the victims and some police records,” Deetjens explained. As with any online love scam, the victim is unaware that the person for whom he or she has feelings is a fraudster. “It is, therefore, essential to begin the investigation by demonstrating, with evidence, that the profile is fake,” he added.

Scammers often use photos that are already circulating on the internet. “We can therefore check if the same photo is found elsewhere on the Internet,” Deetjens said. They then use online research techniques like reverse image search. For more on online research techniques, visit this GIJN resource.

While tracking online scammers, Deetjens also advised keeping a sharp eye out for details: scammers often modify their fake accounts by changing their profile picture, photo albums, and their profile name. However, many forget to also change their profile’s URL address, where one may find the previous name used.

In Deetjens’ investigation, the fraudster posed as a US soldier, Mark D. Kelly. But when Deetjens looked at the profile’s URL address, he noticed that the name on it was someone else, who was linked to a profile in Nigeria. Deetjens called that “a big clue that we are facing a fake account.”

Another best practice: when investigating possible fake profiles online, save frequent screenshots of the accounts, the posts, and the comments, before the scammers can delete them. The Radio-Canada team also uses tools like Fireshot and DumpItBlue+ (available on Chrome) to scroll through comments on a Facebook page.

Deetjens also pointed out that scammers want to save time, so they will use the same approach and even send the same messages to potential victims. Searching Google by using direct quotes from either parts of or whole conversations can help locate other social media impostors or similar accounts from the same person, or even other victims accusing the person of fraud.

By paying attention to the spelling and syntax used by the fake account, Deetjens and his colleagues could tell if a fake account was run by a single person or a team. For example, they had access to some exchanges between one victim and a fraudster.

“The main suspect in the investigation was a man trained at a French-speaking university in Quebec,” Deetjens explained. “However, when reading the exchanges, the handwriting showed that the fraudster barely spoke French, which was not consistent with the profile of the suspect. We later learned that the fraudster behind the exchanges was in fact another accomplice based in Côte d’Ivoire who did not have a complete command of written French.”

Science news site SciDev has done numerous reports on the spread of cybercrime in Africa. Image: Screenshot, SciDev

An illuminating series on cybercrime in Africa, by science news site Scidev in 2016, also gives an insight on how to track down cybercriminals on the continent.

Another resource: The specialized Africa CyberSecurity Mag publishes news as well as trends and statistics on internet security.

The EU-funded West African Response on Cybersecurity and Fight against Cybercrime (OCWAR-C) and the Cybersecurity Capacity Centre for Southern Africa (C3SA) can also be places to go for data, expertise, or training. Faced with the rapid and critical scale of the phenomenon, African countries have set up national response agencies in Kenya, Ethiopia, Nigeria, South-Africa, and Togo.

Tobacco Smuggling

Cigarette smuggling — done to build market share and evade taxes — is one of the world’s biggest black markets. The costs are huge, both personally and financially, fueling smoker-related health costs and robbing countries of billions of dollars in lost tax revenue. It is also a prime driver of organized crime, pouring vast amounts into the pockets of smugglers, who find the risks low and the profits high.

The tobacco black market in Africa is massive. A 2019 World Bank report puts Africa’s annual illicit trade in tobacco at “around 43 billion sticks a year.” It estimated that the illicit cigarette trade accounted for as much as 41% of the tobacco sold in Cameroon, 38% in Ethiopia, and 25% of the market in Algeria, Nigeria, South Africa, and Zambia. The resulting tax loss: about US$10 billion a year across sub-Saharan Africa.

An investigation by nonprofit news network CENOZO showed how tobacco smuggling has paved the way for cocaine trafficking and how this has, in turn, fueled terrorism in the Sahel, which is now plagued by armed groups. Above all, the story alleges that a powerful businessman, considered to be the richest in Burkina Faso, is tied to a vast smuggling network that stretches 5,000 km from Cote d’Ivoire to Libya.

“Cigarette smuggling sounds like nothing, but I have the impression that this is the most prominent of all other trafficking in the war-torn Sahel region,” observed Gaston Sawadogo, who co-authored the CENOZO investigation. “I came to understand through my investigations that one package of cigarettes has the equivalent value of one bullet, one carton equals an ammunition magazine and one container equals one heavy 12.7 weapon.” (Here, “12.7” refers to a Soviet-era heavy machine gun that fires 12.7mm ammunition.)

A second CENOZO investigation dug into cigarette smuggling in Mali. That story reported that, despite seizures by enforcement officials, the involvement of political and economic figures “complicates the fight against the illicit sale of tobacco” and cost the government nearly three billion CFA francs (about US$5 million) in 2017.

Tips for Tracking Down Tobacco Smugglers

Sawadogo suggested taking the time to collect the import authorizations issued to cigarette traders, which are typically issued by the Ministry of Trade. In some countries like Burkina Faso, the authorizations are renewed every year. These documents should include the company, the manufacturer, and the brand of the tobacco products authorized. The authorized brand is important, as some companies will violate this, importing other brands or rebranding other tobacco products. Knowing what their license allows can be a good starting point in an investigation.

Be sure to also check with customs and tax authorities, who may be tracking the illicit tobacco trade. Ask for documents with information on the identity of the cargo, the quantity and value, the origin (to assess if it is suspicious), the importer, and its destination. Experts, data, and analysis can also be found with the African Tobacco Control Alliance, a network of civil society organizations dedicated to preventing a tobacco epidemic in Africa. The ATCA has groups in 39 member countries on the continent. Also worth a look: the Center for Tobacco Control in Africa.

In addition, tobacco industry sources are worth developing – the big companies all have security units responsible for anti-smuggling and anti-counterfeiting work. But the global tobacco industry itself has a long history of being implicated in smuggling, mostly to hook more people on smoking by flooding regions with cheaper cigarettes. Still, reporters may consider asking for industry help in using Codentify, a digital marking and traceability system initially developed by Philip Morris International, later adopted by other major firms and presented as part of their effort to address smuggling.

A slide from a 2012 presentation on Codentify by Daniel Hubert – former Director of the Digital Coding and Tracking Association (DCTA). Image: Codentify

Antiquities Theft

The debate over African antiquities has gained momentum in recent years with campaigns for the restitution of artifacts once looted from Africa during colonization and kept in museums in Western countries. The illicit antiquities trade is a lucrative business, thought to be worth many millions of dollars, and a popular endeavor for organized crime and smugglers across the continent.

This report on the restitution of African cultural heritage, commissioned by the French government and written by French and Senegalese researchers, offers some perspectives on the history of looted African antiquities. According to the researchers, 90% of African cultural heritage objects are being displayed in museums outside the continent.

What’s more, looting and trafficking of antiquities did not end with the independence of African countries. It has been carried on by criminal syndicates that derive vast revenues from it.

“This illegal trade drives corruption, provides an income for criminals and, in several countries, is part of the criminal economies that have emerged amidst violent conflict,” stated a 2020 study by ENACT, a group supported by the Institute for Security Studies and INTERPOL. With a title of Culture in Ruins: The Illegal Trade in Cultural Property Across North and West Africa, the study warns that the illegal trade “continues to cause untold damage to sites and monuments, draining the continent of its collective history.”

Reporters wanting to investigate the issue will find tips and resources in this GIJN guide to investigating antiquities trafficking globally.

Counterfeiting

Counterfeiting is known to be a highly lucrative business and therefore attracts and fuels criminal groups. The weakness of enforcement on the African continent makes it fertile ground for criminal enterprises that traffic in knock-off versions of everything from luxury goods to more sensitive products like pharmaceuticals.

The counterfeiting of medicine is a particularly serious problem for Africa. Some counterfeit medicines bring more profits per kilogram than illicit narcotics, according to the UNODC.

Africa is hit harder by fake drugs than anywhere else in the world, accounting for 42% of all global seizures. The impact on public health is considerable. The UNODC has warned that counterfeit antimalarial drugs may cause an additional 270,000 deaths annually in sub-Saharan Africa.

The Brazzaville Foundation, which focuses on the issue of counterfeit drugs on the continent, has noted that “these drugs are introduced into the market in the same way as drugs, weapons and human trafficking.” In 2020, the foundation brought together six African heads of state, the World Health Organization director-general, and others in a high-profile conference called the Lome Summit, to fight the epidemic of fake drugs. Enforcement is key, the group concluded, noting that counterfeit medicines accounted for an estimated 30 to 60% of all medical products in African countries with poor counterfeiting regulation, whereas the figure was just 1% in countries where regulations were implemented and strictly enforced.

On the continent, reporters or citizen investigators have done various investigations on the issues in their countries, including in Mali, Benin, and Cameroon.

Journalists interested in investigating counterfeit medicines may find these organizations useful for data and insights.

- Medisafe is an EU-funded project that fights against falsified medicines in 11 partner countries: Burundi, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Ethiopia, Ghana, Kenya, Malawi, Rwanda, Seychelles, Tanzania, Uganda, and Zambia.

- The Association of Pharmacy Industry Professionals in Francophone sub-Saharan Africa (Association des Industriels Pharmaceutiques en Afrique Francophone Subsaharienne) represents and defends the pharmaceutical industry, but it is also a major player in the fight against counterfeiting and street drugs in the region.

- Organizations such as the UNODC and the African Organization for Intellectual Property can also be good sources on counterfeiting in Africa.

Table of Contents | Introduction | Chapter 1 | Chapter 2 | Chapter 3 | Chapter 4 | Chapter 5 | Chapter 6 | Chapter 7 | Chapter 8

Additional Resources

Tips for Reporting on Human Trafficking and Forced Labor

Investigating Antiquities and Stolen Art Trafficking

Expert Tips for Following Ships, Smugglers and Supply Chains

Maxime Domegni is GIJN’s Francophone Africa Editor and an award-winning journalist with years of experience in investigative journalism. Previously, he was editor-in-chief of the Togolese investigative newspaper L’Alternative. Based in Dakar, Senegal, he has also worked for BBC Africa as a planning producer for Francophone Africa and as a CPJ correspondent for the same region.

Maxime Domegni is GIJN’s Francophone Africa Editor and an award-winning journalist with years of experience in investigative journalism. Previously, he was editor-in-chief of the Togolese investigative newspaper L’Alternative. Based in Dakar, Senegal, he has also worked for BBC Africa as a planning producer for Francophone Africa and as a CPJ correspondent for the same region.

Aïssatou Fofana is GIJN’s Francophone Africa Editorial Assistant for the GIJN Afrique program. She is based in Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire, and is also a communications specialist,blogger, and a freelance journalist with a strong background in environmental journalism. As a media entrepreneur, she recently co-founded an online media,L’écologiste, to amplify environmental information.

Aïssatou Fofana is GIJN’s Francophone Africa Editorial Assistant for the GIJN Afrique program. She is based in Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire, and is also a communications specialist,blogger, and a freelance journalist with a strong background in environmental journalism. As a media entrepreneur, she recently co-founded an online media,L’écologiste, to amplify environmental information.