Table of Contents | Introduction | Chapter 1 | Chapter 2 | Chapter 3 | Chapter 4 | Chapter 5 | Chapter 6 | Chapter 8 | Chapter 9

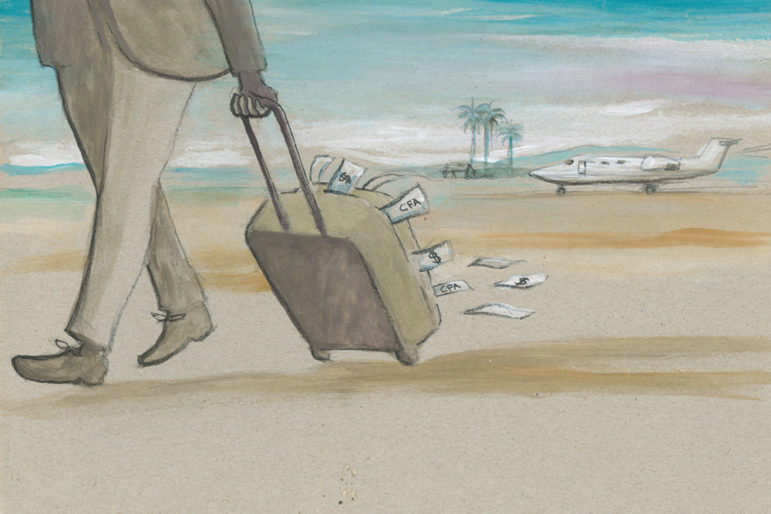

Illustration: Dominique Mwankumi for GIJN

Anyone who enjoys police dramas on TV knows that a criminal needs at least two things: motive and opportunity. Unfortunately, many countries in Africa offer both.

A motive in the rich resources that the continent offers, providing a chance for many to make a fortune. And opportunity in the perception by would-be crooks that countries are open to exploitation.

Financial crime is not unique to Africa. But a combination of ample natural resources and digital services, a legacy of colonialism, and cash-strapped governments have for decades enticed corrupt multinational corporations and individual criminals.

The Problem

Since the start of the millennium, the number of millionaires and billionaires in Africa has soared. By one UN estimate, from 2000 to 2013, the number of so-called high net-worth individuals across the continent rose by 150% — over twice the rate of the average worldwide growth rate of 73%.

While not every wealthy African has a secret to hide, investigations have repeatedly shown that some of the continent’s richest citizens, from Angola’s Isabel dos Santos to South Africa’s Gupta brothers, amassed great wealth through questionable means.

Multinational corporations make even more money in Africa — and have the means to make it harder for governments to find and recover it. In the mining sector, for example, the International Monetary Fund recently estimated that sub-Saharan African countries lose up to US$730 million every year in corporate tax revenue (see chart, right).

Despite the increased focus on the problems and mechanisms of financial crime and wrongdoing in Africa — in part spurred by media investigations like the Panama Papers and West Africa Leaks — money laundering, corruption, and other financial crimes are expected to remain a problem.

Best Practices

Passing the Smell Test

The starting point for any reporter is often right under their nose. In many cases, if it doesn’t make sense to you, it may not make sense to a judge or to a tax inspector.

If a businessman in Malawi operates an East African trading company, why does he need a private bank account in the United Arab Emirates, or Switzerland? If a Canadian multinational corporation signed a contract to operate a zinc mine in Senegal, why did it use a subsidiary in Mauritius to sign the contract?

Corporations and criminals pay high fees to talented experts to design schemes that confuse governments and the public, as well as journalists. “It’s complicated, you wouldn’t understand” is a common refrain by powerful people who don’t want reporters or other anti-corruption watchdogs to dig too deeply.

But a reporter should not be dissuaded by complexity. At the very least, this apparent lack of common sense is a good starting point.

Pay particular attention to any “consultancy agreement.” Financial crime exposés often uncover sham consultancy agreements that allow corporations, entrepreneurs, and politicians to siphon fortunes out of Africa.

Take the time to identify what the consultant is providing and whether the person providing the services has experience in doing so.

In the Pandora Papers, for example, the offshore company of an immediate family member of a Central African president signed a consultancy agreement to receive a 5% commission on the sale of medical devices. That family member is not known for their medical sector experience, yet the contract touts the child as someone who “knows well the African market and benefits from numerous contacts with African businesses.”

Identify the “Enabler”

Every reporter wants the glory of being the first to directly expose the corrupt president, CEO, or billionaire. Reality check: you won’t always be able to.

Don’t let this dissuade you. Remember that no criminal, not even the smartest, can pull off a heist on their own. Setting up a shell company in a tax haven, opening a bank account to launder money, receiving tax advice to hide illicit gains: each step requires the participation of a so-called enabler, a coterie of fixers that includes lawyers, accountants, consultants, and public relations professionals.

Identify and question the enablers who surround your primary subject of interest. You may be surprised where it leads you.

Law, accounting, and financial services firms based in the West, such as in the City of London, have helped corporations and individuals worldwide avoid taxes. Image: Michael Gwyther-Jones/Flickr Creative Commons

Understanding who these enablers are is important for another reason. You won’t always be able to expose a scandal from start to finish. What you can do, however, is lay the groundwork for others. The enabler who helps a multinational corporation avoid taxes or that London-based attorney who represents a money-laundering business tycoon may have also helped others do the same thing.

Identify them, document their involvement in your scheme, and they may lead you to a future investigation.

Multinational accounting firms, for example, have a well-documented history worldwide of failing to identify corporate fraud and providing tax avoidance services to corporations and wealthy individuals across Africa. In 2020, ICIJ and media partners revealed that the global accounting firm PricewaterhouseCoopers earned US$1.3 million helping Isabel dos Santos and related companies dodge taxes. PwC later launched its own internal probe into the work it performed for the Angolan billionaire.

Think about who your subject of interest may be hiding behind or who from their circle may have so far avoided scrutiny.

Long gone are the days when most politicians or powerful people would be foolish enough to put their own name on a piece of paper, contract, or bank account. So also consider your subject of interest’s children, spouse, private secretary, chauffeur, or best friend from high school when investigating their financial holdings and activity.

Read the Footnotes, Go Beyond the Pictures

Look for publicly-traded companies’ annual reports, even if they’re traded outside your country. Who hasn’t read the annual report of a mining company or a construction firm and not been struck by photos of smiling children or a new water pump installed thanks to corporate social responsibility? But read past the fluff. The most useful parts of a company document will often be near the end. Look for keywords and terms like “contingencies” or “contingent liabilities.” In this section of an annual report, for example, a publicly traded company must disclose any future risk, such as a government inquiry. A one-sentence reference to a potential tax dispute is a perfect starting point for a journalist to ask further questions.

Remember that when investigating corporations, the company whose name you know will rarely be all you need. A complex web of subsidiaries — sometimes with names you have never heard of and registered in locations you have never visited — will be where you need to lead you onward. Local officials may be as mystified as you are. “Every transaction performed outside the country is invisible to our tax office given the highly fragile tax and legal framework within our country,” one tax inspector from Madagascar told ICIJ in 2018.

Seek Alternatives When Powerful People Seek to Stop You

Media are often reluctant to pursue revelations about millionaires and billionaires. Why? The economic model of most of the media in African countries, as in most parts of the world, is based on advertising. Often, the same businesses and company owners investigated by reporters are paying the news organization handsome advertising fees. So how do journalists publish investigations when their editors or managing directors express reluctance or outright refuse?

External publishing platforms exist to overcome this barrier, such as the Norbert Zongo Cell for Investigative Journalism (CENOZO). Burkina Faso journalist Sandrine Sawadogo experimented with such an approach during her investigation that was part of the FinCEN Files. In September 2020, Sawadogo revealed that a French-Lebanese businessman used a company in Burkina Faso to buy weapons from Serbia. This purchase allegedly breached local Burkinabe import laws.

She based her exposé, in part, on leaked records obtained from the US Department of the Treasury, which revealed that a bank had flagged the payment by the Burkina Faso company as potentially suspicious. Sawadogo went beyond leaked records and obtained documents from the local chamber of commerce, which offered up names of company directors and shareholders. None of them ever responded to her questions. It was only thanks to a collaboration with a reporter in Serbia that she was able to interview the president of the Serbian company that had sold the weapons and who confirmed the story.

Sawadogo’s employer, L’Economiste du Faso, published the investigation online. But every time the story went live, that site was hacked and her piece was taken down. Her only chance to keep the story alive online was to publish elsewhere. That’s when she turned to CENOZO. Other journalists in Burkina Faso and across West Africa also published Sawadogo’s investigation, giving even more visibility to the investigation.

Tips and Tools

Below is a list of starting points for financial crime investigations. As with all databases, the sources below may be able to help you tell part of the story — but not everything. The following databases include information from a wide range of sources, including leaked information and public records.

-

Online court records from African countries. These databases can be great starting points to learn more about who owns companies or legal controversies in which companies or individuals are involved. In 2021, for example, reporters used ULII.org to learn more about the business deals of Uganda’s then-security minister. In 2022, reporters at ICIJ used KenyaLaw.org to find out more about a court case involving a company accused by Kenyan officials of having avoided paying taxes.

-

Court websites outside Africa can be helpful to identify lawsuits and controversies involving African-based companies that are not otherwise reported on the continent. Legal information websites in Australia and Canada, two countries with a large mining sector presence in Africa, are particularly useful.

-

Data.CENOZO, a new database created by CENOZO; Currently under construction.

-

CBRIS online search offers basic information about companies incorporated in Mauritius. The Indian Ocean island nation is considered a notorious tax haven that has long sought to offer tax avoidance strategies and other financial benefits to corporations with activity across Africa. The names of companies, officers, and enablers may be a good starting point for a story.

-

ICIJ’s Offshore Leaks Database provides information on more than 800,000 companies created in secretive tax havens as well as names of owners, shareholders and directors. The data is drawn from investigations such as the Pandora Papers, Paradise Papers, Bahamas Leaks, Panama Papers and Offshore Leaks.

-

OCCRP’s Catalogue of Research Databases is a wide ranging collection of public data sources, ranging from court records to tax agency portals..”

-

OCCRP’s Aleph global archive of research material for investigative reporting.

-

United Nations Comtrade Database provides detailed global trade statistics by product and trading partner. In 2019, for example, Reuters used this UN database on global imports and exports to expose how gold worth billions was being smuggled out of Africa.

-

United Kingdom property records. Many wealthy individuals and politicians from around the world buy property in the UK. This website allows you to download a list of property owners in the country from 1999 to 2014. Many of these owners are so-called “shell companies” based in tax havens. Though this list is no longer updated, it still helped reporters in 2021 uncover details about the luxury London properties owned by the family of former Kenyan President Uhuru Kenyatta.

-

French company records. Many wealthy individuals and politicians, especially from Francophone Africa, own companies in France. Reporters used this database of companies in 2018 to uncover more details about a luxury home in Paris linked to a prominent Chadian businessman with ties to that country’s ruling family.

Case Studies

The Taking of South Sudan, The Sentry (2019)

For years, US-based nonprofit The Sentry has produced well-documented investigations into corporate and individual malfeasance in Africa. In 2019, that site published The Taking of South Sudan, which revealed how a network of foreign actors — including oil companies and traders from China to the United Kingdom — allegedly helped South Sudanese politicians and military leaders siphon money from Africa’s newest country. The report focused on South Sudanese politicians who allegedly committed crimes and wrongdoing as well as those who helped them, including bankers, real estate agents, and attorneys who set up anonymous shell companies.

GuptaLeaks, Daily Maverick and AmaBhungane (2017)

In 2017, reporters from South African media houses AmaBhungane and Daily Maverick released the first stories in the so-called GuptaLeaks investigation. The investigation involved more than 20 reporters and used thousands of emails and other documents from whistleblowers to reveal how the three Gupta brothers — friends of the then-South African President — had “captured” political decision-making in that country. According to the exposé, GuptaLeaks showed how the brothers “benefited from state contracts and allegedly laundered [billions of rands] [hundreds of millions of Dollars/Euros] offshore” and revealed the role of multinational corporations that had facilitated the alleged wrongdoing. The investigation showed the power of collaboration among reporters from different newsrooms within one country.

Opacity in Cameroon’s Mining Sector, Le Monde Afrique (2021)

In 2021, as part of the Pandora Papers investigation, Cameroonian journalist Josiane Kouagheu revealed that the wife of Cameroon’s former mining minister received shares in a mining company while her husband was in office and responsible for granting mining permits. “This affair is emblematic of the opacity that reigns in the raw materials sector,” a commodity network investigator told Le Monde Afrique, which published the story. While a number of story details came from leaked records, some of the most important findings were already publicly available online. Until that time, however, many reporters had not connected the dots. This is an example of how information already in the public domain can become more significant with extra research and context provided by subject matter experts.

Table of Contents | Introduction | Chapter 1 | Chapter 2 | Chapter 3 | Chapter 4 | Chapter 5 | Chapter 6 | Chapter 8 | Chapter 9

Additional Resources

GIJN’s Guide to Investigating Organized Crime

Lessons from the Pandora Papers: How to Investigate Financial Crime Stories

GIJN Webinar: Investigating Organized Crime in Sub-Saharan Africa

Elza Sandrine Sawadogo is an investigative reporter with L’Economiste du Faso, a leading economic weekly in Burkina Faso, and RSF correspondent. She specializes in financial reporting, illicit financial flows, and corporate fraud, and participated in the Panama Papers, West-Africa Leaks, Pandora Papers, and Shadow Diplomats.

Elza Sandrine Sawadogo is an investigative reporter with L’Economiste du Faso, a leading economic weekly in Burkina Faso, and RSF correspondent. She specializes in financial reporting, illicit financial flows, and corporate fraud, and participated in the Panama Papers, West-Africa Leaks, Pandora Papers, and Shadow Diplomats.

Will Fitzgibbon is a reporter with the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists and coordinator of its partnerships with journalists in Africa and the Middle East. Will has worked on major ICIJ investigations, including the Panama Papers, FinCEN Files, Luanda Leaks, and Pandora Papers.