Table of Contents | Introduction | Chapter 1 | Chapter 2 | Chapter 3 | Chapter 5 | Chapter 6 | Chapter 7 | Chapter 8 | Chapter 9

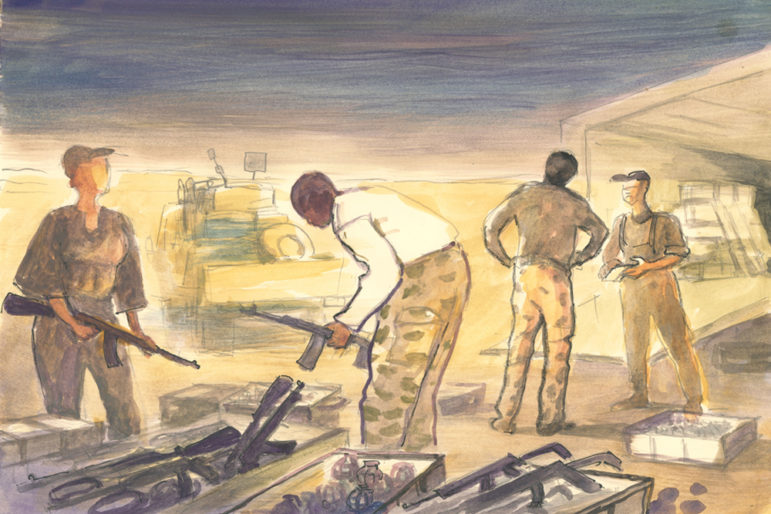

Illustration: Dominique Mwankumi for GIJN

Strife and suffering is big business.

The global arms trade is worth more than US$500 billion dollars annually, and accounts for as much as 40% of the world’s corruption, according to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI). The industry exacts a heavy economic toll while undermining social accountability and fueling human misery.

Yet the global arms trade has less mandatory regulation than the milk or soy industry. The licit and illicit marketplaces are often interconnected, with their legality obscured by arms export controls and “national security” secrets.

The industry’s top 100 companies generated sales of US$531 billion in 2020, SIPRI reported. Arms trading not only relies on global conflict, experts say, but actively encourages conditions that trigger or sustain conflict by providing weapons and other incentives to corrupt governments. To uncover the reality of today’s global arms industry, journalists must unravel a web of jurisdictions, intermediaries, and actors.

Developing nations rarely have the capacity to produce their own weapons or weapons systems and, as a result, they must typically import them from established and often credible private or state-owned companies in developed nations. Global powers, meanwhile, prioritize their national arms industries as a matter of security and foreign policy. The strategy of supplying large-caliber weapons or arms platforms also helps to secure long-term economic deals, as buyers become embedded in certain types of technology and training, such as the NATO or Soviet systems. Many African countries that were supplied by the Soviet Union during the Cold War, for example, continue to purchase the same types of weapons or parts for maintenance because these systems are already familiar to their militaries and it would be cost-prohibitive to switch to a new provider.

Arms may be imported for legitimate reasons such as anti-poaching activity, to secure borders, or to assist other countries with peacekeeping missions. But weapons may also be imported to trigger or sustain internal or external conflict, in anticipation of specific events like elections, and to benefit from corruption through inflated contracts, or diverted to a third party such as a private company or nation facing arms sanctions.

The issue of arms diversion is one reason why the United Nations in 2014 created the Arms Trade Treaty (ATT), a global pact now ratified by 112 governments, including six of the world’s top arms-producing countries. (Notable arms-producing countries that are not parties to the ATT include Russia, India, Iran, and Pakistan. The United States’ participation is in limbo as of publication of this guide.) Yet even for nations that have ratified the ATT, data on international arms deals is often incomplete, contradictory (with discrepancies between importing and exporting nations), or simply never submitted.

For countries that have not ratified the ATT, there is little or no oversight, even where sanctions are applied. Saudi Arabia, for example, is a leading importer of US arms and has, in turn, supplied these weapons, second-hand, to countries in conflict. Sanctions may even increase profits for exporting nations whose state-owned or private companies can charge higher prices to such banned importers.

The UN’s Arms Trade Treaty has more than 110 signatories (indicated in blue), but several of the world’s top arms producers — including Russia, India, Iran, and Pakistan — do not participate. Image: Arms Trade Treaty organization

To evade sanctions or publicity, arms buyers can create a layer of deniability between themselves and a seller via brokers, who use opaque jurisdictions and corporate intermediaries to mediate transactions and provide a legal vehicle for kickbacks structured as payments. Brokers may delegate to lower-level proxies well established in the industry and use them as conduits for both licit and illicit deals. This means governments may protect these arms dealers from prosecution so they can continue to act as a go-between to parties with whom they may not officially trade.

These brokers are also useful when it comes to establishing “offsets” — an integral part of the arms trade where an importing country allegedly benefits from technology transfer or added jobs as a justification for the deal. The supposed cost of these side deals can equal the price tag of the weapons and involve defense-related contracts such as purchasing valuable land as a military base or establishing a mine. The catch is that while it is nearly impossible to verify the legitimacy of offsets, due to the secrecy of arms deals, the added billions that they require are often paid for by the importing government using taxpayer money. In addition to offsets, there are also “add-on” service agreements for maintaining or refurbishing weapons — all of which have become ways to incentivize importing governments into arms deals.

South Africa’s Denel had its weapons shipments to Saudi Arabia and the UAE temporarily halted in 2019 over inspection demands. Image: CTBTO via Flickr

Even countries that seek to avoid fueling conflict can be drawn into questionable deals. For example, more than a third of the weapons produced by South Africa are purchased by Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates (UAE), two countries that have been fueling wars in Yemen and Libya. In 2019, US$1.7 billion worth of Saudi and Emirati weapons orders from South Africa’s state-owned munitions company Denel were temporarily halted because South Africa wanted to include a mandatory inspection clause to track the downstream flow of its arms. Unlike other major arms exporters, the South African government has sought to avoid fueling conflict and arms diversions around the world by adding an inspection clause to the first page of its end-use certificate. The clause mandates that arms inspectors must be allowed to verify the weapons, after delivery, through onsite verification and monitoring of designated military facilities. This includes inspections done on short notice or based on suspected illicit activities, such as on-selling or delivery of weapons to other nations.

The UAE and Saudi Arabia refused to comply with South Africa’s inspection demands, however. Arms manufacturer Denel was nearly bankrupt at the time and so, as an example of how economic pressure can trump good intentions, the South African arms inspector was replaced by a diplomatic inspector with no experience or knowledge of weapons systems. By 2022, South Africa’s weapons were flowing once more to these nations that were actively fueling conflict elsewhere.

While South Africa may appear to have lost its moral backbone when it came to the Gulf nations, it is one of the few countries in the world, alongside Germany, that has made arms inspection a requirement for sales. Thanks to the legacy of apartheid, it is also one of the few developing countries with a sophisticated domestic arms industry. But whether or not arms inspection is mandatory, every end-use certificate requires that all importing governments confirm the arms will not be sold, delivered, or transferred to a third party.

Africa is the largest geographic client for Russia’s state-owned company Rosoboronexport, accounting for over a third of its orders. The Russian government opportunistically targets cash-poor, resource-rich nations or “corridor countries” that barter minerals or geography (such as the use of ports or airports) in exchange for weapons or mercenary forces. As both buyer and seller implicitly agree to wrongdoing, the flow of arms is as secretive as the information involved. This includes the transport process, where details such as the provenance of the weapon and the classification — also known as HS Code — can be concealed.

For instance, the Russian government exports large-caliber weapons, armored tanks, and military helicopters to the Sudanese government. From Sudan, these weapons systems are illegally transferred into neighboring countries in conflict, such as Libya, where the end user is the US-sanctioned Russian paramilitary group Wagner Group, which operates as a private military force.

Other regimes, such as the emirate of Sharjah in the UAE, offer secretive flight registry services. Criminal syndicates or rogue companies may even own private fleets, airlines, or shipping companies that provide an appearance of legitimacy.

As a result, tracking the international flow of arms is a huge challenge. Official disclosures routinely fail to include corroborating data, and instead merely provide a checklist of claims that are impossible for the public, or foreign governments, to verify. In addition, in some countries that do report on their arms trading, a high-powered patron or politician may facilitate illegal activities under a legal framework. And among those nations that regulate the role of arms trading, sometimes the legal definitions of what constitutes illegal activity are vague or contradictory.

Hard-to-catch errors in apparently legitimate transactions include: contracts or shipments that contain more products than are listed, differences in reporting that create inconsistencies by year, and countries categorizing weapons differently. This makes it difficult to understand the production, proliferation, and justification of the arms trade as well as the accompanying debt, barter trades, and trade-offs involved.

So, how can you dig deeper and bulletproof your investigations by leveraging public data?

Tips and Tools

Like any transaction of goods, weapons must be ordered, manufactured, documented, bought, sold, or bartered, and transported from sender to receiver.

There are generally only two layers of legality to arms deals: regulations of the importing and exporting nations and the UN’s ATT. An additional layer exists, if EU countries are involved: the EU Common Position on arms exports.

Unless a country is embargoed or sanctioned, arms trading between nations is a largely private affair with little in the way of checks and balances. But to start your reporting, it helps to understand the basic process of an arms deal.

- An importing government typically advertises tenders or privately solicits suppliers — or has been on the receiving end of lobbying from foreign companies and governments that seek to sell to them.

- The exporting government then authorizes the international sale of weapons, as well as services and technological systems, to the importing party. Each country has its own domestic process for this approval. Find out how the countries you’re investigating operate and the degree to which these sales are public knowledge.

- Weapons are either manufactured and sold by private companies or by government-owned or controlled entities. Private companies are usually not forced to disclose what they sell.

- The weapons may be sold by the exporting government as a “foreign military sale” or by a private company as a “commercial deal,” which still requires exporting government approval.

- Offsets — or add-ons — almost always accompany deals in developing countries and are paid for by the importing country’s public budgets. Though not disclosed, these can increase the cost of the overall arms deal significantly.

Most exporting countries subsidize and protect their private defense sector as a critical part of national security as well as a tool for forging geopolitical alliances. End-user certificates — the primary paperwork signed by the importing government — itemize the goods purchased and declare the weapons will only be used for specific purposes, such as “training, anti-terrorism, security, and stability operations.” Part of the intent of end-user certificates is to prevent arms from being used in atrocities or human rights abuses, or the reselling or “gifting” to pariah states or rogue entities.

A cache of small arms seized by the US Navy in the Arabian Sea that was likely bound for Houthi rebels in Yemen. Image: US Navy via Flickr

However, the reality is that many weapons, especially small arms, sold to one buyer end up somewhere else. The UN arms embargo against Libya, for example, did not significantly affect weapons flows into that country. Corporate secrecy and shipping through false flags or maritime tax havens such as the Bahamas, Liberia, and the Marshall Islands have allowed the country to import illegal or banned supplies in violation of the UN-embargo. Shell companies have also enabled Libya to acquire armored military vehicles, weapons, and bombs from suppliers in the UAE as well as from private Russian security companies.

Countries may not always pay in cash. Pre-financing deals by commodity traders, trade-based financing, and securities such as debt-based financial instruments often play a role in arms deals. In Sudan, gold was exported from Jebel Amir, one of Africa’s largest gold mines in conflict-ridden Darfur, to the UAE as payment. In exchange, shell companies registered in that Gulf nation provided armored troop carriers and other military materiel.

Study the economic role of a country’s defense budget. Many African countries with no active conflicts, such as Botswana and Namibia, spend a disproportionately high amount of their GDP on defense and arms. Study what the government spends each year on defense and with whom, the security threats it faces, and the size and posture of its military. By understanding this, journalists can get a sense of whether corruption is taking place and how it is financed. Combine this with national reports of arms trading by countries.

Read voraciously. Familiarizing yourself with the arms industry requires extensive reading. A compendium of 40 global cases, including many African examples from Nigeria to Tanzania, has been compiled by the World Peace Foundation. Each case study comes with key facts, primary actors, and the context in which it unfolded. In Tanzania’s case, leading UK arms company BAE eventually admitted wrongdoing to a UK court and paid a fine related to a $12 million kickback used to facilitate the sale of overpriced and ill-suited military air radar systems for civil purposes. Several other cases, including the company’s dealings in South Africa, have raised suspicions of alleged bribery.

Look for clues in the conflict around you. Whether it is poaching of endangered species, timber trafficking, or confiscation of water and minerals, those involved often acquire arms to militarize resource-rich areas as a means of extracting profit. Identifying areas under the control of terrorists helps explain the flow of arms and the financing behind it. See, for example, West Africa’s W-Arly-Pendjari Complex, the continent’s last intact ecosystem and the place where two journalists and the founder of an anti-poaching unit were gunned down in April 2021.

Search for trade organizations and exhibitions. Exhibitions and trade organizations are used by global arms manufacturers and African buyers to market products, make deals, and build relationships. The Africa Aerospace and Defense Expo, for instance, advertises air, land, and sea arms from private and state-owned manufacturers such as Russia’s Rosoboronexport. Such events are a good way for journalists to develop sources and more importantly, to become familiar with the industry. Similarly, the Aerospace and Defense Industries Association of Europe is frequently attended by African arms brokers and high-level military officials.

Map national and international arms manufacturers by weapon, producer, and supply chain. Manufacturers who produce explosives, small arms, and aeronautics often work in very different spaces and require different supply chains. Some companies publicly disclose the products they sell. In fact, most weapons can be identified by public reverse-image searches. By identifying the weapons, journalists can map and identify, to a reasonable degree, arms importers and maintenance companies. The nonprofit IPIS mapped out manufacturers and agents of more than two dozen categories of arms across Africa. Compile original data whenever possible, and make use of existing datasets to cross-reference what you’ve found.

Use legal, media, sanctions lists, and corporate data to identify agents and brokers. Currently, there is no international consensus defining arms brokers. Though these actors rarely take physical possession or ownership of the weapons, legal cases, media investigations, and sanctions routinely disclose names of brokers tied to questionable deals. Creating a spreadsheet of brokers and countries, with associated scandals and companies, helps to see the bigger picture. Southern Africa’s SAFLII, the UK’s BAILII, and the US’s PACER are good places to create alerts. Meanwhile, OCCRP’s Aleph and Open Sanctions provide the most comprehensive global sanctions-related data.

Tap publicly verified resources to analyze politically-connected owners and operators. This helps when investigating whether the person flying on a private jet or the company behind the fleet itself is an illicit actor. For instance, when the Republic of Congo sought to purchase 500 tons of weapons just prior to elections in 2016 and 2021, officials used a private carrier — Silk Way Airlines, an entity closely tied to Azerbaijan’s ruling family — to transport the arms supplied by Saudi Arabia. By understanding who is involved, interests become more apparent.

Speak to the experts. Institutional knowledge resides in NGO staff and journalists, and in former employees who worked in the arms industry. Scour social media such as LinkedIn and even company staff lists from past years through internet archives to identify relevant names. UK-based Shadow World Investigations, run by former South African arms deal whistleblower Andrew Feinstein, and South Africa’s Open Secrets, led by arms expert Hennie Van Vuuren, are two organizations replete with resources and contacts. Another helpful resource involves investigators working on various special commissions such as the UN Panel of Experts.

Understand national legislation, particularly around public procurement and the defense industry. The key to military contracts is learning what is legally allowed by the importing and exporting countries, and where loopholes and inconsistencies may allow for deals to go ahead without public tender or in secret. The EU Common Position has slightly higher criteria and consequences compared to the ATT, which is voluntary disclosure, but these too are easily circumvented.

Arms registries. The UN Register of Conventional Arms (UNROCA) was created in 1991 to document the official trade in arms between nations through voluntary disclosures. This information is publicly accessible and may expose secrecy on the part of one government when it fails to report arms sales. The registry includes small arms, such as machine guns and rocket launchers, as well as major weapons systems like armored combat vehicles, attack helicopters, and longer-range missiles. Another informative resource is the SIPRI, which offers country reports, data on military expenditures, arms transfers, arms embargoes, and military assistance between nations.

Flight records: Aviation datasets such as FlightRadar24 and FlightAware can provide information on planes including tail codes, country of registration, and recent activity, while aviation forums like Reddit’s r/aviation or Airliners.net provide unique information observed by pilots and technical crews around the world. Be sure to also check GIJN’s planespotting guide and C4ADS’ Icarus flight tracking platform. Such details also allow for investigations based on common air platforms. For instance, Antonov cargo planes, formerly manufactured by the Soviet Union, are still commonly used by the military in West Africa. Identifying registries also exposes where planes sold are not airworthy.

Shipping and maritime records. For maritime shipping, start with GIJN’s Tracking Ships at Sea, and move on to datasets such as Marine Traffic, Import Genius, and Panjiva for data on routes, products, senders, receivers, dates, and addresses. Like planes, ships must be registered in a country and owned by a government, company, or person. Red flags on shipping include tax jurisdictions specializing in maritime and aviation secrecy such as the Marshall Islands, Bermuda, and Liberia.

Corporate structures. In addition to identifying ownership and management of companies through company registries, seek out the legal and financial structure of the firms involved. This includes the purpose of the company, countries of operation, details of linked or associated companies. Also, it’s worthwhile to match the origin of assets and revenues, what taxes, losses, and profits are recorded and where, as well as whether any litigation is ongoing that may force legal discovery. This requires scouring public data such as court and tax records.

Audits and freedom of information requests. Many African countries do not have access to information laws and where they do exist, they are often weakly enforced. In Uganda, for example, a 2005 law allows exemptions for state security. Both the state and private companies may drag the process out for years, but it is worth an attempt. Also, check for audits and official inquiries. One OCCRP investigation reported US$800,000 in kickbacks from a Uganda deal for eight used and poorly maintained MI-24 helicopters from Belarus. The information came from a special commission in Uganda that also detailed the intermediaries. The report helped explain the broker’s newly created bank account in Switzerland.

Look for intermediaries, offsets, and countertrades. Many importing countries require that sellers “reinvest” technology from a deal back into the country, but this may be done in ways that often enable corruption. These so-called offsets and various barter agreements are worth close scrutiny. To date, no registry of brokers, offsets, or counter-trades has been made mandatory by the ATT nor the EU’s Common Position.

Case Studies

Nigeria’s Armsgate Scandal, Premium Times (2015)

From 2007 to 2015, and particularly under the presidency of Goodluck Jonathan, key national security advisors of the Nigerian government allegedly spent more than US$2 billion on corrupt kickbacks — framed as “failed contracts.” The accused have denied the charges and trials for several of them are still ongoing more than seven years later. These alleged bribes were part of a complex deal involving over 500 weapons contracts worth billions, ostensibly to fight Boko Haram. The story was broken by Nigeria’s Premium Times and later covered by the BBC and others.

Angolagate Scandal, Maka Angola (2019)

More than two decades ago, Angola’s dictatorship spent US$790 million through a series of official French government intermediaries to evade sanctions and purchase weapons sourced from Eastern Europe. Bribes of US$56 million were reportedly paid to politically-exposed persons throughout the government of Angola — including, allegedly, the then-president’s daughter — working through men with a long history of brokering deals for the regime. The scandal was exposed in increments by Angolan investigator Rafael Marquez through his online blog, Maka Angola.

Niger’s Arms Baron, Jeune Afrique (2022)

This story centers around a businessman implicated by Nigerian officials in a major scandal in which nearly US$1 billion in aid money was allegedly diverted to rigged bidding and overpriced deals involving Russian and Chinese arms. Roughly US$240 million of these deals were said by Nigerian authorities to be fake or never delivered. Initially exposed by Niger journalist Moussar Aksar of L’Evenement, the arms deals were also investigated by OCCRP, which built on Aksar’s intrepid work.

Editor’s Note: Some parts of this chapter have appeared in GIJN’s Global Guide on Investigating Organized Crime.

Table of Contents | Introduction | Chapter 1 | Chapter 2 | Chapter 3 | Chapter 5 | Chapter 6 | Chapter 7 | Chapter 8 | Chapter 9

Additional Resources

Reporter’s Guide to Investigating Organized Crime

Reporter’s Guide Investigating Arms Trafficking

South Africa’s Extraordinary Year: Journalists Turn the Tide Against Corruption

Khadija Sharife is a senior global investigator with the Organized Crime and Corruption Project. She is the former director of the Platform for the Protection of Whistleblowers, has a master’s in law, and has contributed to investigations about illegal logging in Madagascar, corruption in Angola, and arms trafficking in Cote d’Ivoire.

Khadija Sharife is a senior global investigator with the Organized Crime and Corruption Project. She is the former director of the Platform for the Protection of Whistleblowers, has a master’s in law, and has contributed to investigations about illegal logging in Madagascar, corruption in Angola, and arms trafficking in Cote d’Ivoire.