Illustration: Smaranda Tolosano for GIJN

GIJN is introducing a new series in which we ask 10 questions of leading investigative journalists in tough press freedom environments around the world. The aim is to provide insight and inspiration to other journalists, to offer some practical tips, and to raise awareness about the impact that watchdog reporters and editors are having at this critical global moment.

For this inaugural edition we interview Vinod K. Jose, executive editor of The Caravan, India’s premier long-form journalism magazine. An alumnus of the Columbia Graduate School of Journalism in the United States, Jose leads an intrepid team that champions accountability and media independence in the face of rising autocracy and Hindu nationalism in the world’s largest democracy.

- Of all the investigations you’ve worked on, which has been your favorite, and why?

Vinod K. Jose: The best long-form stories we carried in The Caravan had serious elements of investigation, be it the profile of a politician, watching the growth of a corporation, or looking back at a historical event. But in what we call through-and-through investigative journalism, there must be over two-dozen stories that captured national attention. The best investigations involved forming a hypothesis, advancing the reporting, testing the hypothesis step-by-step with each finding, carrying out a diligent systematic inquiry through all aspects of reporting, and — once the story is written up — distrusting every fact as a potential mistake and putting it through a rigorous bullshit-detector process.

But for the way the state and judiciary responded, I would put the Judge Loya death series as among the most interesting. A judge who refused to acquit Amit Shah — the second-most powerful man in India, who is also Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s political lieutenant of four decades — died under mysterious circumstances. The judge died a few days after he refused to take a US$15 million bribe to acquit Amit Shah.

What was initially seen as a single story grew into 28 follow-up stories; four of the senior-most judges in the Supreme Court carried out a press conference stating stress on the judiciary, and part of the material on this story went into the first-ever impeachment process against the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of India. This was unsuccessful, since the opposition did not have the requisite numbers. The afterlife of this story still lingers.

We developed the story through sources cultivated in big political offices and got information about doctors who manipulated the postmortem reports of the judge. We also traced 17 former employees from different parts of the country… And we proved the medical evidence produced by the government was wrong. Each follow-up story was done under tremendous pressure.

- What kind of impact has your work had, and what topics would you like to see watchdog reporters tackle more deeply in India?

VKJ: Often a good piece of investigative journalism, if it exposes the people in the government, draws the attention of the opposition, social media, and independent media. Compromised legacy media organizations try to ignore a story as much as possible since they don’t want to hurt the government in power. Our investigative stories went viral in India — whether related to the Rafale fighter jet deals, the multi-million-dollar payoffs made to national leaders of the ruling BJP, or the national security advisor’s son operating his company in the tax haven Cayman Islands. [Editor’s note: The national security advisor’s son has denied this claim, and has filed a defamation suit against The Caravan. The magazine is standing by its story in an ongoing case.]

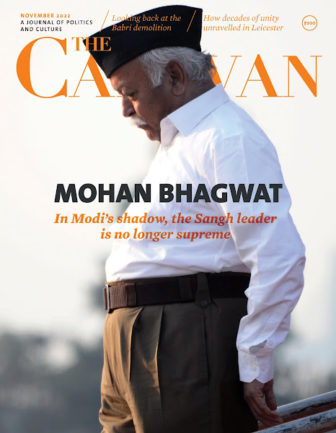

The latest issue of The Caravan, edited by Vinod K. Jose. Image: Screenshot

- What are the biggest challenges for watchdog reporting in India — and what has been the greatest challenge you’ve faced personally?

VKJ: The biggest challenge for watchdog reporting in contemporary India is the overall lack of institutional support from media investors, publishers, and editors. An investigative journalist finds it very hard to push a story through the biggest media platforms in India, who play the role of gatekeeper, often conveying this message to the watchdog journalists: “Don’t bring an investigative story. You will be paid your salary without that.” The big media interests align well with the political and social interests of the ruling ideology, and with the rise of [PM] Modi. Whether it is the political, administrative, or journalistic class, there’s very little challenge to the prime minister through government reporting. The greatest hurdle we face in India is to operate in an increasingly authoritarian ecosystem, where sources and whistleblowers also fear for their lives. This has myriad implications, including the targeting of journalists and the weaponizing of the law by the government or allied interests, or the harassing of sources who talk to journalists or leak documents. Journalists and sources are operating at a time when the price they pay for siding with the truth is higher than ever before.

- What is your best tip or trick for getting and then maximizing accountability interviews?

VKJ: To persuade a shy or uncooperative source, the investigative journalist should not come across as transactional. Sources are human beings, too, and might be unclear about why they are imparting important information or documents, or turn cold half-way through the process. The journalist should try to relate to the source — without diluting his or her ethical values — by appealing to their human quality. The mannerisms of the investigative journalist depicted in movies hardly shows the work to get a shy source to cooperate.

Do just the opposite. What helps put somebody at ease? What works to reduce the social distance between the journalist and the source? Get the source to relate to you, and vice versa. Kill the class, caste, racial, gender, social, and political prejudices of the journalist, so that the reporter comes across as a better person to the source, and the source is put at ease.

- What are your favorite reporting tools, databases, or apps for investigations?

VKJ: In the Indian context, you begin with the publicly available databases for corporations and individuals with political and business histories. The statutory declarations from public databases are a good place to start. Then there are the international databases that track the movements of ships that we have relied on — 52wmb is quite good. The Indian census database, when compared to countries like the United States, is not very comprehensive for investigative journalists, and crime data has not been processed by public agencies in a way that is useful for muckrakers. Indian prison data is also not very useful. By and large, the right to data — even though it exists in India as a citizen’s right to know — is a chase like any other, similar to tracking down a source or document. Often it goes through the long-winding written petition route through the Right to Information Act, but the Act has already been diluted by the same Congress Party government which brought the law in the first place, and later by Prime Minister Modi. It is not in any government’s interest for citizens to know, and certainly not for an authoritarian one.

- What’s the best advice you’ve gotten thus far in your career — and what words of advice would you give an aspiring investigative reporter?

VKJ: Work hard. Identify big interests and don’t be happy with B+ stories, go for the A+. Be curious all the time, be excited about stories, and push everyone to go from a 60% story to a 90% one. Don’t fall for an opinion in an investigative story. See it yourself to believe it. Consider yourself not operating in a newsroom, but in a war room, where a mistake can be fatal. When the aim is to punch, don’t prick, but punch like Muhammad Ali — give all the big knocks, bring gravitas to the story through hard labor spent on reporting, investigations, and deep digging. These are some of the pieces of advice I got from my mentors, and I would gladly pass them on to an aspiring investigative journalist.

- Who is a journalist you particularly admire, and why?

VKJ: If I had to pick just one, I would go with Seymour Hersh. His stories have left an impact over half a century, from Vietnam to Iraq. He hit the ground for the human side and he is also great with documents. When I met him at his office in Washington, DC as part of a college trip, I asked him for advice, and he said: “If your mother says she loves you, you must check it out.” I’ve tried to follow the spirit of that advice as much as I could.

- What is the most memorable mistake you’ve made as an investigative editor — and what lessons did you learn?

VKJ: We came close to publishing a story that was possibly a plant — most likely by a government agency, or someone close to them. This happened in the run-up to the 2019 national election, and a time when we were breaking one big story after another. This particular story had passed all due diligence, and the story was ready to be published. But some doubts still lingered in my mind and we slowed down to exercise one more round of due diligence. We pulled some strings and reached out to a few unconventional sources for this round of scrutiny, and learned the document the story relied on was fake. Thankfully, we got saved from what would have been a big mistake. Often a source or a journalist in your own team might knowingly or unknowingly bring stories that may not stand up to scrutiny, so it is important to always be on guard. Seymour Hersh’s advice on verifying even a mother’s love stands true.

- How do you avoid burnout in your line of work?

VKJ: To have occasional breaks helps. Also, one cannot always go in fifth gear, so pulling the levers to the fourth or third for a few weeks, and swinging back to the fifth again, is important. But I must admit, this may not always happen as easily as one wants.

- What about investigative journalism do you find frustrating, or do you hope will change in the future? What would you like to see in five years?

VKJ: With the rise of autocratic tendencies all over the world, there are far fewer local resources for investigative journalism. A more decentralized way of supporting investigations is important. I would like to see an increase in hyper-local as well as global investigations. With people on social media breaking news before a journalist does, and with opinion being free and for all, going forward, one way a newsroom will have to justify itself must be through its boldness and thoroughness in carrying out investigative journalism. So investigative journalism is what will differentiate between content creators and a newsroom of some worth.

In five years, I would like to see investigative journalism grow fashionable in public culture, too, both at hyper-local and national levels. So the background probe of a village officer or the day-to-day dealings of the president of the ruling party — the local and the national — should create informed conversations for the public.

Additional Resources

One Magazine’s Fight for the Indian Mind

Why Journalists in Autocracies Should Report as If They’re in a Democracy

Rowan Philp is GIJN’s senior reporter. He was formerly chief reporter for South Africa’s Sunday Times. As a foreign correspondent, he has reported on news, politics, corruption, and conflict from more than two dozen countries around the world.