Protestors demonstrate at the Iranian embassy in Brussels, Belgium, following the death of Mahsa Amini in police custody. Image: Shutterstock

Many Western media reports on the nationwide anti-government protests in Iran — triggered by the death-in-custody of 22-year-old Mahsa Amini — have painted a picture of internet shutdowns and an oppressed population isolated from news about itself.

Yet one independent, exiled Iranian news outlet, Amsterdam-based Radio Zamaneh, has told GIJN that its audience traffic – both within the country and in the diaspora – has doubled since the start of the protest movement on September 16. Driven by the slogan “Zan! Zendegi! Azadi!” (“Women! Life! Freedom!”), the public dissent has expanded beyond the brutal enforcement of mandates requiring women to wear hijab head coverings to a broad anti-government movement, with rolling protests and acts of civil disobedience affecting more than 100 cities and towns. The death toll has passed 250 civilians, and public trials have been scheduled for more than 1,000 protesters. There are fears of an even bloodier crackdown to come, following a public October 29 warning from the chief of Iran’s elite Revolutionary Guard, which had not yet deployed its notorious security units.

According to Joris van Duijne, executive director of Radio Zamaneh – a GIJN member – general internet access remains robust, and censorship-circumvention technologies and a local determination to connect continue to provide tens of thousands of Iranians with access to independent news. “This is an audience that really wants and needs to see what journalists are digging up, so the work counts,” he says.

A recent story in The Washington Post described how another independent, exiled outlet, IranWire, helped to break the story of Amini’s death, and is working hard to record the full national death toll from the government’s crackdown on the protests. The number of dead has already exceeded 272, according to the Human Rights Activists News Agency (HRANA).

Radio Zamaneh has taken a different, very local approach – focusing on human interest stories, and digging into the detail and background behind individual crackdown atrocities. For example, this story focused on the death of Behnam Layeghpour – a tattoo parlor owner in the northern city of Rasht shot by security forces, who then prevented medical assistance for him.

Radio Zamaneh profiled the death of Benham Layeghpour (left), whose memorial service (right) drew protests in solidarity despite the attendance of state security officers. Image: Anonymous social media sources, via Radio Zamaneh

Van Duijne says details like these help to cut through the chaos and numbers of mass protests – and that this applies to investigative work on major stories as well.

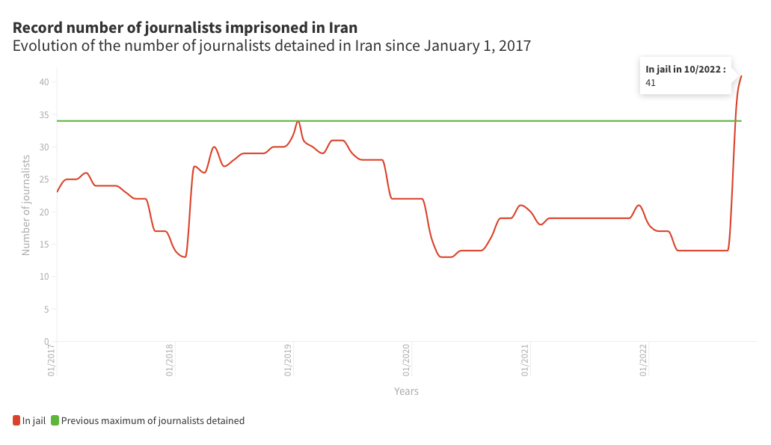

Meanwhile, 40 journalists have been detained during the protests, including two women reporters who revealed new details of Amini’s death and funeral – Niloofar Hamedi and Elahe Mohammadi – who have been jailed on charges of being CIA-trained foreign agents, leading to unified demands for their release from journalists and civil society organizations. According to Reporters Without Borders (RSF), Iran is now the world’s “biggest jailer of women journalists in the course of this crackdown.”

GIJN: How has your team approached news coverage of such a wide protest?

Joris van Duijne: The protests are just going so fast — they can be on a dozen street corners in a given city on any given night. It is very hard to keep track of.

This has been going on for six weeks, and our journalists are working around the clock – everyone is exhausted. We have limited capacity, as a total team of around 15 journalists.

Early on, we decided we are not a human rights documentation organization, and we are not collecting numbers – we’d rather be a source for those groups, by doing solid journalism, and digging into individual cases.

On the 40th day after Mahsa Amini’s death, protesters marched toward her burial site at Aychi cemetery in Saqqez, Iran. Image: Courtesy of Radio Zamaneh

The human interest element is very important for our audience, as is the full picture from long-form journalism – to go beyond the numbers, to provide a detailed account of what happened to individual protesters, to track their journeys to that situation. We see reflected in traffic numbers that human interest stories are the most popular – stories about victims of the brutality; people being shot in the back.

Part of what we do that is more news oriented, and less investigative – but which is important at this time – is a news roundup in Persian every day at 9am, European time. These are long articles on what has happened during the previous late afternoon, evening, and night in Iran.

We’re producing about seven stories daily, though I personally would like to see fewer total stories and more in-depth reporting. For the near future, we really want to focus on underreported things around this event. Everybody covers Sharif University – the big university in Tehran where many intellectuals are based – but we’ve seen stuff at middle schools where the kids have started protesting, and strikes and boycotts at local levels. That level of this uprising spreading into every aspect of society is where our focus is now.

GIJN: To what extent are internet connections and social media channels available to Iranians?

JvD: There is a misperception – fed partly by civil society – that we’re dealing with mass internet shutdowns in Iran. This is simply not the case. The internet has been disrupted, but very locally, or temporarily, and as a means of crowd control. The regime has gotten a lot more technically savvy in singling out individual 4G (broadband cellular) masts, and blocking out a radius around a protest where your cellular data is not available. It has also throttled internet speeds for certain hours of the evening when people take to the streets. Our assessment is that that is to prevent the upload of videos.

The outages were much more widespread during the 2019 protests, and for multiple days.

In terms of channels: Instagram basically rules, in terms of numbers. We see Telegram and Signal being widely used for communication in Iran right now, but especially among activists and journalists – the same with Twitter, which is widely used by civil society.

The regime has found very specific ways to block individual apps – WhatsApp has been down during much of the protests. On a daily basis, we hear ‘This or this service is down’ – but Iranians hop services, just like they hop VPNs – and this includes email, which is low bandwidth and very expensive to completely black out, though Gmail has suffered there in recent weeks.

It’s clear the government would like to adopt a Chinese model, where the internet is nationalized with national apps that work well, and international apps that are dysfunctional.

GIJN: Can you share some of your techniques for reaching audiences within Iran?

JvD: Our distribution strategy is a mix. When it comes to the ever-expanding capacities of Iran in terms of censorship, it is our assessment that one of the last things to go will be email. As such, a lot of our emphasis is on email distribution. During the current protests, we have increased our newsletter from weekly to every other day, and expanded our email distribution list. There are also communication apps that rely on email protocols, such as Delta Chat, which we recommend to our audiences.

Joris van Duijne, executive director of Radio Zamaneh. Image: Courtesy of Radio Zamaneh

Even today, our website should function for audiences in Iran without a VPN, because we have invented a technique in the backend of our site that makes our blocked website available without a circumvention tool. It is a backend proxy, where people only use our website URL and the website itself is capable of pulling content from other places. Other newsrooms can actually acquire this in-browser proxy technology from us – it’s part of our economic strategy.

Many users access our content through Psiphon, a very good circumvention app that’s free for audiences, and easy to use. Others hop around between VPNs, and we also use things like mirror sites.”

[Editor’s note: In a prior interview, Van Duijne described Radio Zamaneh’s use of ‘mirroring’ services, which replicate censored websites on less vulnerable servers, and recommended the VirtualRoad service for investigative outlets with limited capacity.]

GIJN: What can you safely share about how you access sources affected by the protests and the crackdown?

JvD: We work different time zones, including shifts matched to Iran’s time zone, and reach out to people through traditional channels, social media, and encrypted channels. So we use well-known apps like Signal and Telegram. Unfortunately, WhatsApp has been down, but our journalists hop between alternate channels of communication, just as our audience does.

There are also some limited document sources. There is a lot more data than Western journalists might imagine in restricted environments like Iran, as in Russia and other places. These governments have statistics bureaus which pump out stats, and it is a day job to sift through them, but it can help. We work with data in partnership with organizations like Iran Open Data, which does much of the legwork. Years ago, when a colleague of mine was investigating online troll armies used by the Revolutionary Guard, they were astounded to find that trolling was publicly procured, with data attached.

GIJN: What does the independent media landscape for protest coverage look like?

JvD: In terms of exiled independent outlets, it’s pretty much us and IranWire. We know the people at IranWire, and we have a lot of respect for their work.

But a lot of media coverage of this event is from public media, rather than independent sites. BBC Persia has a very big desk; Voice of America; Radio Free Europe, Deutsche Welle, and all those outward-oriented broadcasters. There are also two independent TV stations operating from London: Iran International, which does hard core, breaking news-type journalism; and Manoto, which also provides entertainment.

Our audience has doubled since the start of the protests – we see that in organic traffic, in social media referrals, in search numbers. We also see it through our circumvention traffic, having spoken to our technical partners like Psiphon. It’s weird, because everyone is talking about internet shutdowns, and here our traffic is increasing, but I think people are more eager to get the news when it’s restricted.

GIJN: How do you verify facts in such a restricted environment?

JvD: It sounds horrible to say, but deaths and killings are the easiest data points to verify in times like these. There is a semi-full picture we’re seeing from human rights groups and Zamaneh works with these groups. Verification is hard, but our team goes step by step, whether dealing with social media video or victims’ claims.

For instance, we had a source inside Evin Prison. [Zamaneh talked to a prisoner at this notorious prison for political detainees as part of an investigation into the true causes of a major, deadly fire on October 15.] It is incredibly difficult to verify witness accounts from a prison like this, but we embedded his account [of the fire] in wider reporting, verifying the context of what the prisoner said. We also draw from accounts from family members.

The number of journalists jailed in Iran has surged to a record high as anti-government protests have swept across the country. Image: Screenshot, Reporters Without Borders

GIJN: What protest-related topics do you think watchdog journalists should dig into more deeply?

JvD: For the international audience, it’s important for journalists to look at the level of patronage and corruption within Iran – and its military-industrial complex – because a lot of people benefit from this regime. That helps sustain them, and is often ignored.

There is a lot of sanctions evasion going on in Europe that reporters can dig into, but there is also a lot of over-compliance with sanctions that is harmful to ordinary Iranians. Companies just don’t know if such-and-such a business is safe, and the legal department says ‘back off,’ and then people don’t export, say, medical goods to Iran, which are exempt.

I think more in-depth reporting on political prisoners is important right now – the landscape of who is in jail, and why – and also on these strikes happening in solidarity with the protests.

International journalists should collaborate more – if, say, they wish to investigate the Basij plainclothes units, they should talk to Iranian journalists. Also: What is the role of different ethnicities in the current movement?

GIJN: What has surprised you about this protest? And what outcomes do you foresee?

JvD: What surprises me is the scale of this — that I had not foreseen — and the timing. To be blunt, I had thought the terror or deterrent effect of the killing of 1,500 protesters in 2019 would have lasted the regime longer, before people would go back into the streets.

We’ve seen these waves of protests through recent Iranian history – student protests in 1999, the Green Movement in 2009 was massive, and then some smaller outbreaks, then a major protest movement in early 2019. But I think people were less enthusiastic then than they are now. This is a very broad-based protest, with people from different backgrounds – socio-economic, ethnic, and ideological. Of course, the central role of women in this movement is unprecedented, and has made the dissent kind of upbeat.

At the same time, it is important to remember that the authorities in Iran have dealt with discontent for 40 years, and they are very well equipped to crack down. People are very united in what they do not want. But the regime has been very smart in making sure people do not unite in what they do want – what the alternative should be to the current system. So we saw that in the first few days of unrest, pretty much every thought leader in Iran was re-arrested — from labor movements, environmental groups, human rights groups — everyone involved with setting an agenda for the future. Especially intersectional leaders were targeted, because people who represent more than one interest are extra-scary for the government.

There is much we don’t know. Are the protests in one town coordinated with protests in another? We don’t yet know.

This is not a protest against the hijab — a false assertion I hear in Dutch media, for instance. No, they’re protesting against forcing anything on women. It’s about freedom.

Additional Resources

‘Reporting from the Outside’: Lessons from Investigative Journalists in Exile

How Exiled Journalists Are Investigating in the Arab Gulf States

Security Manual for Covering Street Protests

Rowan Philp is GIJN’s senior reporter. He was formerly chief reporter for South Africa’s Sunday Times. As a foreign correspondent, he has reported on news, politics, corruption, and conflict from more than two dozen countries around the world.

Rowan Philp is GIJN’s senior reporter. He was formerly chief reporter for South Africa’s Sunday Times. As a foreign correspondent, he has reported on news, politics, corruption, and conflict from more than two dozen countries around the world.