Journocoders Indonesia

In a positive sign for data journalism in Southeast Asia, the volunteer Journocoders Indonesia community has more than 1,000 informal members. Image: Journocoders Indonesia

The early days of the COVID-19 pandemic saw our daily habits change drastically, overnight. We learned not to leave our houses during lockdowns, do remote work over Zoom calls, feel constant anxiety about the health of our loved ones, and wake up to look at the latest COVID numbers first thing in the morning — on interactive maps with scary red circles across the globe, or line charts showing cases rising day after day.

For better or worse, the pandemic made us all avid consumers of data journalism.

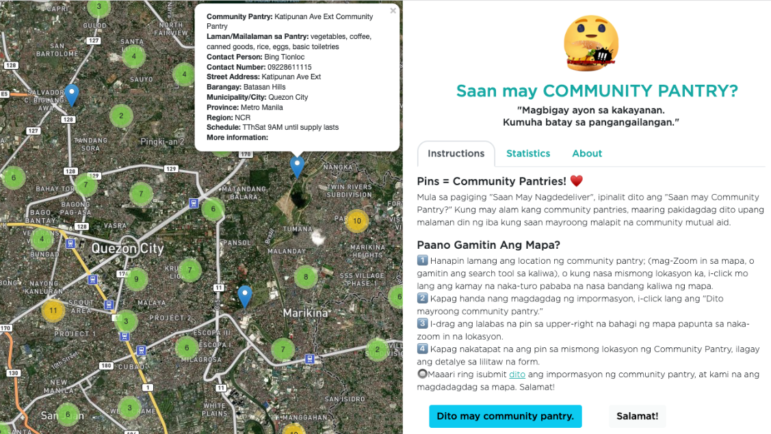

The Philippines endured one of the longest and strictest lockdowns in the world during the pandemic. In April 2021, a year into the lockdowns, a grassroots movement emerged. Starting in Quezon City in Metro Manila, people started leaving items such as rice, canned goods, and face masks for anyone in need. Such community pantries started sprouting up all over the country in the coming weeks and months. While people mobilized on the ground to distribute food and necessities, a community of technologists was also mobilizing online. Ben Hur Pintor and his friends from the Philippines’ open mapping community — who were used to creating online maps that promote progressive causes, from queer-friendly safe spaces to places where violence against women occurred — immediately got to work building an online map of the community pantries. People were able to use the map to find out where the nearest pantries were located, what kinds of items were available, and when they were open. As of June 2022, the map is still up and running, showing over 900 pantries across the archipelago, proudly displaying the scale of this grassroots movement which stepped in to fill a much-needed gap.

Online maps of community pantries in Manila by open mapping activists has helped to develop data skills and data literacy in the Philippines. Source: Saan May Community Pantry

“People now have a better understanding of numbers and charts,” said Kuek Ser Kuang Keng, a Malaysian data journalist and trainer who is one of the most influential proponents of the field in Southeast Asia. “They look at the numbers every day to help them make decisions about whether to go shopping or not, whether to go to school or not. That really helped data journalism develop during these two years.”

Over the past decade, data journalists have been trying to push the frontiers of digital storytelling. By weaving together graphic design, interactive media and data analysis, this new breed of journalists are as comfortable writing computer code as they are writing prose. They interview data to unlock insights about everything from corruption to environmental degradation, and present these to their readers through beautifully designed visualizations.

Spearheaded by newsrooms such as The New York Times in the US, and the Guardian in the UK, data journalism had been gaining momentum since the early 2010s. In Asia, publications such as Hong Kong’s South China Morning Post were using beautifully illustrated data driven infographics in their print newspaper and online.

The 2010s saw the entire media landscape be disrupted by the emergence of social media, and the decline of traditional revenue streams for newspapers such as advertising and subscriptions.

My own journey into data journalism and civic technology began in 2015 when I started organizing data training workshops with journalists and technologists in my home country of Myanmar. Since then, my work in the field has connected me with incredibly passionate and brilliant people across Southeast Asia and beyond. Kuek Ser Kuang Keng pioneered data journalism in Malaysia and trained data journalists in various countries around the world. Aghnia Adzkia, a pioneer in data journalism in Indonesia, currently runs one of the most successful volunteer communities for learning data journalism in the region. Ben Hur Pintor works with grassroots communities and government agencies alike in the Philippines to open up data to the public and arm them with data skills to make good use of these.

Starting New Things

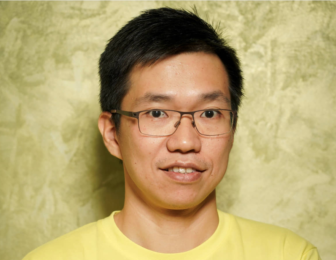

Kuek Ser Kuang Keng

Malaysian data journalist Kuek Ser Kuang Keng. Photo: Courtesy Kuek Ser Kuang Keng

In 2012, Keng was a news editor at the online news portal Malaysiakini. He had a background in engineering, which gave him a knack for numbers. “Whenever there was data to be crunched, they would usually send it my way,” he said about his colleagues. After doing some data-driven reporting on the Malaysian elections, he decided to apply for a Fulbright Scholarship to study data journalism for his master’s degree at New York University. This took him down a path to not only being an innovator in Malaysia, but across the region as well.

Upon his return from the US, Keng founded his own company, Data-N, eager to start spreading data journalism in Malaysia. He quickly realized: “This thing is so new that nobody knew about it, and I should go outside of Malaysia to look at regional newsrooms.”

He found that while newsrooms were eager to undergo a digital transformation, most of them set their sights primarily on growing social media audiences. However, performing well on social media platforms was akin to playing a game where the rules kept changing. Audiences shifted from Facebook to Twitter to Instagram, and the platforms could decide to change their algorithms without warning, leading to drastic changes in what kinds of content did well. It was a constant uphill battle to drive traffic one’s way.

“If you are looking for traffic, you are not looking for high quality journalism,” Keng said. “You are looking for fast-fashion journalism. You want things to be sexy, to be beautiful. But these don’t last long.”

It was only after a few years of running data journalism workshops across the region in countries ranging from Nepal to Singapore, Indonesia, and Thailand that he once again collaborated with his old employer, Malaysiakini, to develop its newsroom’s data journalism capacity. Malaysiakini — being a pioneer in the digital media space in Malaysia — was keen to develop its paid subscription business model, which required that it invested in producing high quality and engaging journalism. Keng believes that newsrooms that want to add more subscribers need to convince people that they have high value content that they should pay for — and data journalism was definitely one avenue to high quality, engaging content.

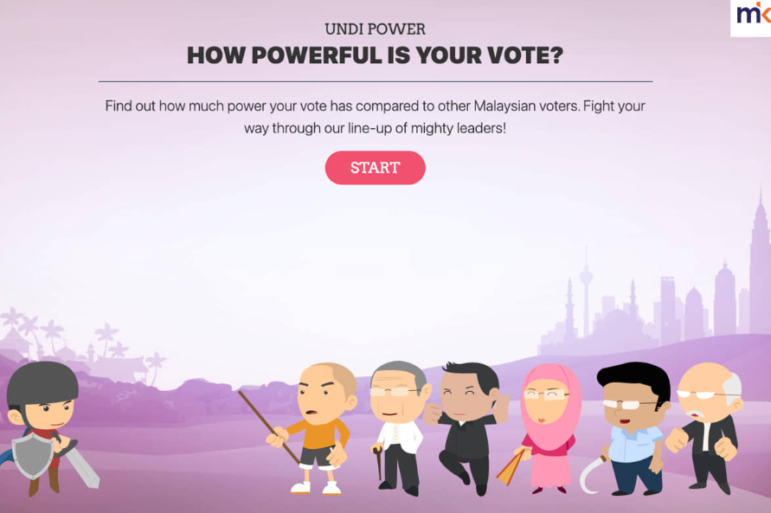

Malaysiakini has gone on to produce multiple innovative data journalism stories and products. Their COVID dashboard was nominated for a Sigma award, a prestigious global award for data journalism, and so was an investigation they conducted into deaths that took place in police custody. They also experimented with new interactive formats for informing their readers, including a game that allowed readers to see how gerrymandering affected the value of their votes.

Source: Malaysiakini

A news game from Malaysiakini designed to explain to readers how gerrymandering in their constituencies has diminished the power of each citizen’s vote. Graphic: Malaysiakini

Malaysiakini was also involved in one of the most famous global investigations of recent years: the Paradise Papers. Together with dozens of partners via the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists, their investigation tracked down Malaysian businessman Jho Low “seeking safe haven in the Cayman Islands and the British Virgin Islands (BVI) following the outbreak of the 1MDB scandal” — one of many scandals uncovered in the global investigation.

The kind of innovation that Malaysiakini has been able to create is not often seen in Southeast Asia. With COVID-19, audiences have become more attuned to data journalism, yet only a handful of newsrooms have been able to consistently produce data journalism stories with not only top-notch design and visuals, but also in-depth data analysis and research. Some prominent ones include The Straits Times and the Thomson Reuters Graphics team in Singapore, and data-focused outfits such as Punch-Up in Thailand and Kontinentalist in Singapore.

Success in this field requires collaboration. Cross-border investigations with other newsrooms such as in the Paradise Papers are one way through which this could happen. Collaboration also has to happen within a single newsroom among a team with various specialized skill sets such as software developers, designers, data analysts, and reporters. It also involves working with actors outside of newsrooms such as government officials, non-governmental organizations, and civic technologists, who often play a crucial role in unlocking the most fundamental raw material of data journalism: the data itself.

Data is a Team Sport

Photo by: Aghnia Adzkia

Indonesian data journalist Aghnia Adzkia. Image: Courtesy Aghnia Adzkia

By day, Aghnia Adzkia is a Jakarta-based senior data and visual journalist at the BBC World Service, where she is part of a team of data journalists, designers, and software developers who work with BBC journalists across East Asia to tell data-driven stories. By night, she runs a volunteer community of Indonesian journalists who meet up every month to learn data journalism skills, called Journocoders Indonesia. The group has more than a thousand informal members, and their regular meetups are attended by 60 to 80 journalists.

“I’ve taught a lot of journalists, and I always hear them complain that they are not good in math,” she says.

For Aghnia, the most important skills that journalists need to learn to get into data journalism are the basic skills for doing simple calculations in spreadsheets. Since most people who become journalists do not come from quantitative backgrounds, sometimes even learning the basic logic of how to calculate simple insights from a dataset can be a challenge.

After four years of organizing Journocoders Indonesia and mentoring journalists on data skills, she observed that journalists who have picked up some data skills will start to slowly incorporate data elements into their stories such as a chart or a map, instead of jumping into becoming full-blown data journalists. She shared that Indonesian newsrooms rarely have “data journalist” as a designated role. When she was starting out in the field, there were only a few newsrooms that did, including the now defunct Beritagar, where she took a role as a data journalist before joining the BBC.

Aghnia was studying for her masters in data journalism at Goldsmith’s College in London when she found out about the original Journocoders meetup group, based in London. She attended a few of their sessions, and was so inspired by the idea of a community of journalists learning data skills that, when she returned home after her studies, she started Journocoders Indonesia.

She has also invited international data journalism practitioners such as Keng to mentor at her workshops. “People like Keng and I, we love communities. So we build them.” Despite being run by only a small team of volunteers, Journocoders Indonesia has trained university lecturers to adopt data journalism modules into their course curricula, and has taught workshops in remote places such as Sulawesi and Aceh.

“At the national level you can easily get data online, but when you want to write about local issues based on a city or a remote island, you might not be able to get the data online; you need to call the individual government departments,” says Aghnia. “You need to know where the data comes from, which institution or organization has the data, and then you start asking them.”

Aghnia’s point about data availability rings true not only in Indonesia but, in my experience, in most other Southeast Asian countries as well. I was once working with a Myanmar journalist on a story about the country’s health care system, who was having trouble finding datasets about hospitals on the official ministry of health website. Only when she picked up the phone to ask a ministry official about why the datasets on their website had not been updated did they realize that their data was out of date, and promptly uploaded the latest data. Not every encounter with a civil servant is as fruitful as that phone call, but, often, finding ways to build collaborative relationships with people within the institutions who publish the data is crucial in nudging government institutions toward a culture of transparency.

Will This Have an Impact?

Filipino data activist Ben Hur Pintor. Image: Courtesy Pintor

Ben Hur Pintor is the kind of person a data journalist turns to when they are in need of data. He is an advocate for open data in his native Philippines and a data training lead for the Open Knowledge Foundation, a global organization whose mission is to make all non-personal data openly available for the public to use and share.

Pintor’s specialization is in geospatial data, and the open mapping community he is part of practices a type of data-driven activism called “counter-mapping.”

He explains that counter-mapping means “to use the technologies, applications, and methodologies that have been historically used by the state and private corporations to oppress individuals, and take that and flip it on its head to counter aggressive development where people lose their land and their livelihoods.” An example of counter-mapping would be using a drone to map out areas where people have settled and planted their crops to counter the government’s claim that the land was sitting idle and could be reclaimed by the state.

Counter-mappers preparing an unmanned aerial drone to survey areas that have been marked out for development. Image: Courtesy Counter-mapping PH

Although his activism often requires him to confront authorities, he also sees tremendous value in building trust with potential allies within the government. For instance, he worked for two years with the provincial government of South Cotabato, a province near the southernmost tip of the Philippines, to help them open up all the data related to tenders and public procurement. The relationships that he built with the civil servants there ensured that even though it had been several years since he worked with them, the provincial government was still publishing all the procurement data using the systems and workflows that he had set up.

A mosaic image assembled from drone footage by counter-mappers countered government claims that Indigenous land was idle. Image: Counter-mapping PH

Pintor admits that his approach to working with data has changed a great deal in recent years. Back in the day, he just wanted to “build cool stuff,” work with the newest technologies, and make pretty maps. These days, he starts every project from the perspective of the audience’s needs. “It’s not always the cool stuff that people need. The cool stuff might be good for your ego, it might make you famous, but it might not be good for the people you work with, and the people you want to have an impact on.”

“I’m now less selfish about how I work with data,” adds Pintor.

However, the same cannot be said about many others who are using data and technology. Especially when reflecting on rampant misinformation campaigns during the lead up to the recent national elections, Pintor worries about the shrinking civic space and the growing dangers of misinformation in the Philippines.

“I know people who are very good with data, but they can still be victims of fake news and misinformation. A lot of our work is based on the assumption that if people know how to work with data, then they will become better citizens. I sometimes wonder if that assumption is correct.”

A Lot of Work Remains

The threat of misinformation came up in all my conversations with Keng, Aghnia, and Pintor as a top priority issue for data journalists and data activists to confront.

Aghnia conducts workshops in remote parts of Indonesia that are prone to natural disasters to counter the kinds of misinformation that spread during periods of disaster, when the difference between being informed and misinformed could be life or death. If a social media post says, for example, that a location is safe from a flood when it actually is not, it could cause tremendous damage.

Last year, Keng piloted an investigation that analyzed data from thousands of social media posts. He looked into how disinformation from China had been picked up by mainstream Malaysian newspapers and Facebook groups with large followings. For example, there was a rumor which spread in 2019 — at the time of the protests in Hong Kong — that democracy activists had thrown a Molotov cocktail at a school bus full of children. Within two days, this false reporting was appearing all over Malaysian social media. Keng plans to replicate this kind of investigation with other newsrooms in the country.

Keng remains optimistic that the coming years will see data journalism and collaboration playing more of an important role in investigative journalism. In his recent work with the Pulitzer Center — collaborating with investigative journalists on environmental issues — he found that “data is a huge part of their investigations.” The journalists routinely had to use satellite imagery and data from geospatial analyses of deforestation.

“If journalists want to tackle global issues like climate change or deforestation, they will have to learn how to collaborate, and a lot of those collaborations are based on data,” Keng said.

In my own work in this field, I have always noticed that those who are drawn to data journalism are self-starters who always find a way to make it through the challenges. They all got started in the field when most people had not even heard of the term data journalism. They had to invent their own job descriptions.

Growing communities, building trust, and fostering collaboration were things they had to do from day one of their careers, and none of them seem to be slowing down one bit, but instead are looking ahead and asking how their work can be more impactful.

For better or worse, our lives are going to revolve more and more around data, and working as a data journalist — or data activist, as Pintor puts it — will continue to be “frustrating but fulfilling at the same time.”

This piece was first published by Penang Monthly, and is republished here with permission.

Additional Resources

‘We Were Born Digital’: Premesh Chandran on the Success of Malaysiakini

One Man’s Mission to Spread Data Journalism Across Southeast Asia

Yan Naung Oak is the founder of Thibi, a Singapore-based data and design consultancy. His work mainly involves helping journalists and civil society use data more effectively. He is originally from Myanmar and currently resides in Singapore.

Yan Naung Oak is the founder of Thibi, a Singapore-based data and design consultancy. His work mainly involves helping journalists and civil society use data more effectively. He is originally from Myanmar and currently resides in Singapore.