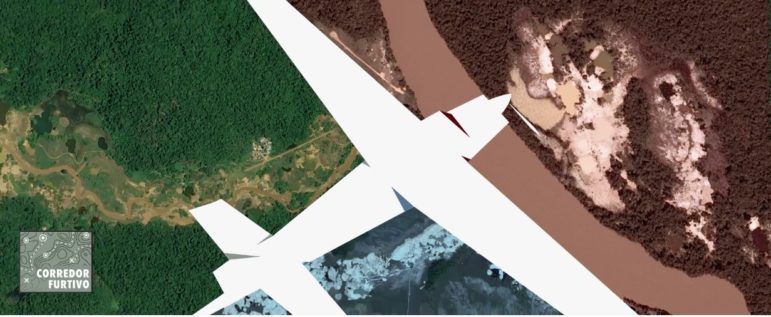

In the Venezuelan Amazon, many hours away from the country’s capital, traces of the devastation caused by illegal mining can be seen from the sky.

Although this area is officially protected, and home to a number of Indigenous communities, organized crime groups have seized control of illicit quarries, destroying the rainforest, and even built runways to take their bounties overseas, according to NGOs like Human Rights Watch. While observers suspected that the country’s devastating economic crisis had made the problem of illegal mining worse, it was hard to grasp the real magnitude of the problem.

But a collaboration between the Spanish newspaper El País and the Venezuelan investigative outlet Armando.info — a GIJN member — used satellite data, machine learning, and field reporting to try and paint a definitive picture of the problem and to establish the driving forces behind it. They identified over 3,000 mining locations — most of them illegal — and deforested areas equivalent to 40,000 soccer fields, many of them close to clandestine runways, in the south of Venezuela.

The investigation took almost a year and is called Corredor Furtivo – or Secret Corridors. The team found that some of those airstrips were used by organized crime cells to move gold and traffic drugs.

During the past several years, Venezuela has faced a profound socio-economic crisis that has both amplified illicit activity and exacerbated political corruption, chronic shortages of food and medicine, the highest inflation rate in the region, and the deterioration of public services like electricity and clean water. This project also had to face logistical and physical security challenges related to the country’s situation. The difficulty in finding fuel, which only gets more scarce the further you go from Caracas, makes it extremely hard for reporters to cover issues in remote areas of the country. In addition, there is an increased threat of violence in the Arco Minero del Orinoco, the region where much of the illegal mining happens.

Joseph Poliszuk, Armando.Info’s co-founder and the leader of this project, has been reporting on this area since 2006. This time he wanted to do something different: Rather than investigating what happened at one mine, he wanted to build something that would allow them to show the bigger picture.

“It’s not new to point out that a huge amount of gold leaves through clandestine flights” from Venezuela, the team reported. “But this collaboration… allowed us to show for the first time on a map the strategic points set up by the smuggling groups to take illicit cargo out of the country by air.”

The reporting team used AI to identify and map illegal mining sites and clandestine airstrips across southern Venezuela. Image: Mapbox, Courtesy of Armando.Info

Using AI to Map the Project

The project started with traditional journalism: thanks to their field reporting, the team was able to create a database showing the areas where they already knew there were mines. The next step, says Poliszuk, who first started working with artificial intelligence as a journalism fellow at Stanford University, was to use artificial intelligence (AI).

With the help of experts from Norwegian organization Earthrise Media — which uses machine learning, AI, and human-centered design to address climate change — and the Pulitzer Center’s Rainforest Investigations Network, the team created an algorithm programmed to recognize and associate images similar to aerial shots of open-pit mines and clandestine runways, in order to identify these patterns in the jungle.

“Thanks to these first examples, and with the help of experts, we taught the algorithm to look for similar spots” on the map, Poliszuk explains.

Armando.Info co-founder Joseph Poliszuk led the reporting team. Image: Alice Vergueiro / ABRAJI (Creative Commons)

Another motivating factor to use computer-assisted intelligence was the COVID-19 pandemic. With the whole country in lockdown, it was harder to report from on the ground, even as reporters suspected that illegal mining activity would boom as the rest of the country ground to a halt.

“We decided to do this right in the middle of the pandemic because there was still news happening,” says Poliszuk, listing illegal trafficking and the spread of paramilitary groups during the pandemic as key concerns.

The resulting investigation, published in January 2022, used high-definition satellite images to find thousands of locations where gold was being illegally mined in two of Venezuela’s most forested regions. This kind of mining involves cutting down all the trees in the area and pumping in huge quantities of water. Afterward, there’s nothing left except craters full of toxic wastewater surrounded by vast tracts of deforested land.

Amid the clandestine mines mapped by the project, reporters found one in the Gran Sabana, a high plateau of 10,000 square kilometers that serves as an access threshold to the region of The Tepuis — a biodiversity hotspot that is home to animals and plants that don’t exist anywhere else on Earth. They found another mining hotspot inside Canaima National Park, a UNESCO World Heritage Site that is home to the highest waterfall in the world. Many of these mining sites were in areas home to Indigenous communities that have to live alongside the illegal actors, endure the environmental impacts, and, in some cases, even participate in the destruction via forced recruitment.

Of course, beyond just tracking the existence of these illegal mines, the reporting team wanted to identify who was behind them.

Citing three anonymous sources, the team found one illegal gold mine, located just two kilometers from an Indigenous community, was controlled by Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) dissidents – remnants of a guerilla organization that once controlled huge swathes of the territory across the border.

But FARC isn’t the only armed presence in the country. The second part of the reporting project – The Who’s Who of Criminal Cartels South of the Orinoco – set out to map organized crime groups with a presence in the region. It found two groups formerly involved in the armed conflict in Colombia now had a presence in Venezuela. Although historic enemies, these two forces have a no-aggression pact in mining areas and are believed to be forcibly recruiting Indigenous populations. Helping their illicit activities: local politicians, who allegedly turn a blind eye no matter the socio-economic cost.

This second part of the series was reported by analyzing three years of news and official figures and creating their own database. “This project,” says Poliszuk, is a hybrid of data journalism and “traditional, in-the-field reporting.”

Armando.Info built a database detailing the different criminal groups south of the Orinoco River in Venezuela. Image: Screenshot

Staying Safe While Reporting on Organized Crime

María de los Ángeles Ramírez, a reporter based in Venezuela, was one of the journalists who covered the illegal mining on the ground. She insists that, for this kind of reporting, taking care of yourself is key, something the team ensured by having a security protocol in place before, during, and after interviews.

A colleague who reported from Amazonas, another Venezuelan border state, was monitored by phone throughout her reporting trip from the moment she left Caracas. And they weren’t afraid to change tack when things got dangerous. In Amazonas, for example, they had to adjust their plan after receiving an alert that armed groups in the area knew that there was a journalist present.

María de Los Ángeles Ramírez reported on the ground in southern Venezuela. Image: Screenshot

“Doing field work in the Venezuelan south is challenging. You have to know beforehand what you want to do, where you want to go, and which communities are you going to visit,” explains Ramirez, adding that it was still important to do this on-the-ground reporting alongside the mapping and database elements of the project. “This allowed us to have confirmation and testimonies of the things we were seeing in the database.”

“Combining technology and field reporting was a success for this project,” agrees Lisseth Boon, a Venezuelan data and design journalist with experience in covering illegal mining who was not part of the investigation. “Especially when we take into consideration that we are talking about a really hard to access area.”

For each of these reporting trips, the team established how often they would check-in with each other, which phone numbers they were going to use (in order to ensure they were using a provider that worked in the jungle), and alternative emergency contacts in case the newsroom couldn’t get hold of the journalist.

Ramírez used an app called Life360, which allows a group of people you trust — your “circle” — to track you from afar. It has a built-in feature that can share your real-time movement, updating your location every two seconds. They also used Confluence, a remote, team workspace where you can organize a project, and Signal, a messaging app that uses end-to-end encryption, to safely share information. They also followed safety recommendations by the ACOS Alliance, which the Pulitzer Center is a member of, such as performing a risk assessment and identifying routes, transport, contacts, and a communications strategy in case of an emergency.

Ramírez also highlights the importance of working together with El País, which published the project at the same time. “El País was key in data visualization and editing. Not only did they allow the work to have more diffusion, but they shielded the post-production,” Ramírez says. Roughly 10 people from El País worked on this project.

Lessons Learned, and Long-term Impact

Boon says that, although the project was well-received, the crisis in Venezuela is such that she suspects tangible impacts will be hard to spot for now. But, she adds, that does not mean that the team’s efforts were in vain. It’s still important to report on this topic, she says, so people outside the country can learn more about what’s happening “and have a clear diagnosis” that could eventually help organizations address the crisis.

Poliszuk says that one of the biggest takeaways from the project was being able to confirm the complaints of the Indigenous peoples in these regions, who for years have warned about illegal mining and the devastating environmental impact it can have without any official response.

Ramírez says working on this type of investigation has changed the way she works. “This project taught me how to systematize information,” she says. “I have many years of experience reporting in this area, but this dataset taught me how useful it is to do daily monitoring and add to it. That allows you to understand things better.”

“Our plan is to keep growing this database, there’s a lot that we can do starting from there,” Ramírez adds. “The reality is that these networks of organized crime don’t know about borders. This isn’t just a problem of the Venezuelan south: this is a problem of the whole country and the whole region.”

Additional Resources

Investigating Forest Fires Amid a Data Vacuum in Venezuela

How Armando.info’s Exiled Reporters Keep Reporting on Venezuela

Venezuela’s Lisseth Boon’s Favorite Tools for Design and Data Visualization

Mariel Lozada is associate editor of GIJN en español and a Venezuelan freelance journalist based in New York City. She has a Master’s Degree in Engagement Journalism from the Craig Newmark Graduate School of Journalism at CUNY, and has reported on health, gender, migration, and human rights issues in three countries.

Mariel Lozada is associate editor of GIJN en español and a Venezuelan freelance journalist based in New York City. She has a Master’s Degree in Engagement Journalism from the Craig Newmark Graduate School of Journalism at CUNY, and has reported on health, gender, migration, and human rights issues in three countries.