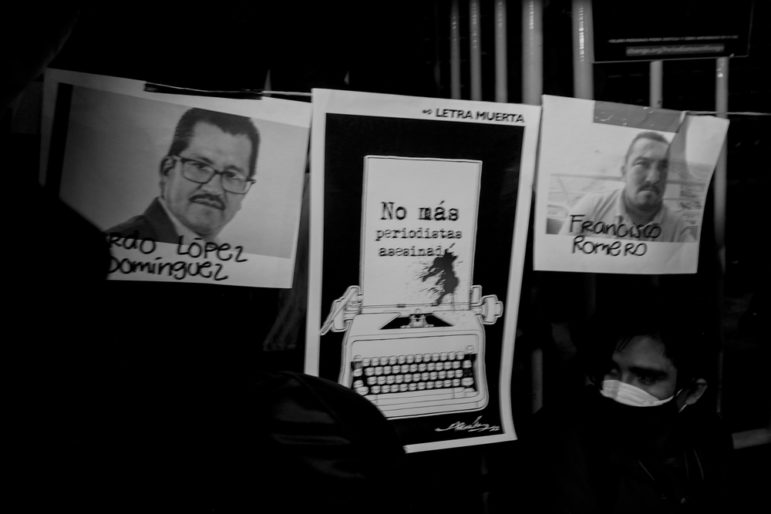

Protest signs over the killing of two Mexican journalists in March. So far, nine journalists have been murdered in Mexico since the beginning of 2022. Image: Shutterstock

Rosental Alves is an expert on freedom-of-the-press issues, digital journalism, and tech trends in Latin America. Originally from Brazil, he has extensive reporting and editing experience across the continent, and holds the Knight Chair in Journalism at the University of Texas-Austin’s Moody College of Communication’s School of Journalism. In 2002, he founded the school’s Knight Center for Journalism in the Americas (a GIJN member organization). Each year, the Center hosts the International Symposium on Online Journalism (ISOJ), on the impact of the digital revolution on journalism.

GIJN’s Spanish editor, Andrea Arzaba, caught up to Prof. Alves at this year’s ISOJ, and spoke to him about such topics as the current state of independent media in the region, tech trends for small newsrooms, and what comes next for the Knight Center.

GIJN: What are the main challenges that investigative journalists face in Latin America right now?

From Rio to Austin: Rosental Alves has prepared thousands of journalists for the age of digital media. Image: University of Texas at Austin

Rosental Alves: Investigative journalists have always had many challenges in Latin America, especially because the region has had two kinds of journalists: lapdog journalists and watchdog reporters. Watchdog journalists always face opposition from powerful elites and governments, simply because they don’t understand the role of journalism in a democratic society. So even when we have experienced democracy — which for many countries has meant intervals between dictatorships — we’ve always seen journalists facing many obstacles.

However, there is a new phenomenon now, which is the attack against democracy and journalism as the main target. Investigative journalism, in particular, is a victim of this international movement against democracy. And that creates new challenges for reporters. For example, after a couple of decades of openness, we see movements to close information. Also, the organized attack against journalists in social media, especially female investigative journalists, is another challenge that has been added to the traditional ones.

GIJN: Do you observe a backlash against independent media?

Alves: Yeah. Now we have sort of a long spring of democracy for many countries. This is the longest period of democracy that we have experienced globally. Nevertheless, we have seen the replacement of traditional military dictatorships with authoritarian regimes, from the right and from the left, that undermine democracy.

To talk about specific examples, I can name Venezuela, a classic case with the Chavismo [movement] starting in 1998. Then, the press was the target. The new model, that Chavez called ‘the socialism of the 21st century,’ would not be able to exist with watchdog investigative journalism, so the attacks against the press began. There was a warlike situation between the media and the authoritarian populist. The first victims then were the truth, and the quality of journalism. Then he exported that model. And the same problems of misunderstanding the role of watchdog journalism in democratic societies repeated in other countries like Bolivia, Ecuador, and Nicaragua.

Nicaragua is now an extreme example of this backlash, where there is a dictatorship with the façade of democracy, and with a specific, violent, and intense target against journalists and the media. The other example is El Salvador, where you have a president who seems to be convinced that society doesn’t need journalism anymore. Not only is he disrespectful to the basics of the democratic system, but he believes that he can connect directly with people, so free press would not be necessary, in that distorted, authoritarian view. Then you have [President Jair] Bolsonaro in Brazil, to give another example, who systematically imitates Trump in the United States, in making the press the number one enemy, and this is very bad in all senses.

GIJN: What can you say about the case of Mexico?

Alves: In the case of Mexico, it’s all encapsulated in one media event, which is “las mañaneras” — an event the president calls a “press conference” that happens every day at 7:00 a.m. However, it’s not just a press conference. The President of Mexico invented a way of disintermediation, trying to use YouTube to go direct to the public with his propaganda and, very often, attacks against journalists and media organizations that are immediately followed by his army of social media activists. So, the “mañaneras” are, in part, propaganda, in part press conferences, in part, another way to attack the media and the opposition.

I’ve been following technology and journalism for decades. I predicted that we would enter a new media ecosystem that would be radically different from the previous one. And now we are seeing the darkest side of it. Many people in my generation thought that the digital revolution would lead to a more democratic world, because of easier access to information. Yes, there is a bright side, but it seems that anti-democratic forces learned how to use those tools before the journalists and people who believe in liberal democracy. We are seeing the consequences. I hope there is still time to wake up and save democracy, which does not exist without a free press.

GIJN: How do you think technology is influencing journalism in the region right now?

Alves: Twenty years ago I was trying to predict the future of journalism in the digital media ecosystem and before one of my public presentations, someone introduced me as “a cyber enthusiast.” I was intrigued by that and commented that, yes, I was a cyber-enthusiast, but not a cyber-utopian. I knew that technology would open new possibilities for journalists to do their work, especially investigative journalism. But I also knew that a dark side would come, we would enter uncharted, dangerous waters.

Investigative journalism has had important benefits from technology around the world, and especially in Latin America, where many journalists were quick to work on data journalism and engage in transnational collaboration. They have had a strong participation in investigative projects of the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists, like the Panama Papers, helping to create the structure of investigative journalism at a global scale, in ways that would be unimaginable years ago. So there is a bright side and in Latin America in particular, you see transnational investigative journalism flourishing with examples, just to cite some: CONNECTAS founded by Carlos Eduardo Huertas 10 years ago, El CLIP, by Maria Teresa Ronderos, among so many other great initiatives.

GIJN: What trends do you observe?

Alves: There is a proliferation of new, native digital news organizations with an emphasis on investigative journalism, but also with an extraordinary diversity in all aspects, from the hyperlocal, to state, to national, and finally international. And with specific beats like the environment, health, and migration. I see that, according to the directory of Sembra Media, there are more than 1,000 new organizations — a mass of media that is not as concentrated as it used to be. In Brazil, the Knight Center helped the creation of an association of native digital organizations so they can have a collective voice. And I think that many other countries in Latin America should think about associations like Ajor.

The other trend that is new in Latin America is nonprofit journalism. I don’t say that nonprofit would replace commercial, but that it would occupy a space in this new media ecosystem created by the digital revolution. In Latin America, I was faced with skepticism when I talked about the phenomenon of non-profit journalism in the US and predicted that similar phenomenon could arrive in the region, even in a more modest way. I was told that was a gringo thing — that this is very particular to the US. And I always said, the fact that you don’t have a tradition of philanthropy in your country — and you don’t have one of the most beautiful things in American society, which is the give-back concept — that doesn’t mean that you could not develop that. Right?

So today you see high quality investigative journalism from an organization like Agência Pública in Brazil, or CIPER in Chile, which was created before ProPublica. Yeah, it is possible. In Mexico you have Mexicanos Contra la Corrupción y la Impunidad (MCCI), which is a very innovative model. It is not only a nonprofit organization, but also a model you had never seen before anywhere in the world, as it’s a combination of a newsroom and a lawyer’s office. So they investigate on one side, practicing serious investigative journalism. And on the other side, the lawyers go to the courts in some cases and take action.

Alves’ Knight Center annually hosts the International Symposium on Online Journalism. Image: Screenshot

GIJN: What were the highlights of ISOJ 2022?

Alves: I would mention some topics: the vitality and sustainability of nonprofit journalism; diversity, equality, and inclusion throughout newsrooms in Latin America; and government subsidies. You know, Europe has a tradition of subsidizing journalists, but the US has not. And now, after the crisis of the industry, journalists are thinking about it, especially at a local level.

We talked about regulation, and how it’s not only just about government subsidies, but about the dominance of the platforms, especially Google and Facebook. And how they can play a role in the distribution of news through those platforms; also how they can remunerate journalists. In that sense, I believe that human beings use technology and they create problems, but they also use it to create solutions. It was also important to talk about tech trends, including Web3 and the metaverse.

For ISOJ 2023, we just announced the dates.

GIJN: What learning experiences can you share about the massive open online courses (MOOCs) that the Knight Center has produced over the years?

Alves: Since we started in 2002 — we are celebrating our 20th anniversary — one of our main activities were online courses…We served 7,000 journalists in Latin America and the Caribbean. In 2012, we embraced the idea of massive courses. And in the past 10 years, we have organized 102 MOOCs that have reached 271,189 students, in 200 countries and territories around the world.

This shows that continuing education for journalists has never been so important. Because we are the generation of the transition to a media ecosystem or information ecosystem that is rapidly changing to something that has never been seen in the past. And what GIJN does — not only with peer-to-peer learning but also specific training — now it is fundamental. And we see it with other organizations as well, like IRE. And we see journalists thirsty for new knowledge, so we are very proud of our achievements with the MOOCs.

GIJN: What have been the most popular topics covered in your MOOCs, and what would you like to explore next?

Alves: Investigative journalism has always been the most popular in Latin America. Data visualization and data journalism have always been popular, which are related to investigative reporting.

New topics we want to cover include mental health, trauma, and safety. My generation has been negligent in not recognizing those issues, so I try, at the Knight Center, to recognize them.

GIJN: What about the magazine you produce: the LatAm Journalism Review (LJR). How do you choose the topics you cover?

Alves: We have a team of journalists based in Colombia, Mexico, Brazil, and here in Austin. And we try to be on the radar of what is interesting in the journalistic industry. Unfortunately, we do not publish as many positive stories as we would like to, because journalism has been under attack. So most of our stories are about problems, but we also cover stories of success.

We are working on a safety series and, by the end of it, we will produce an ebook. Just like we did with diversity. Our main mission is to help journalists and promote press freedom in the region.

GIJN: What comes next for you and the Knight Center?

Alves: We are in a soul-searching moment for the Knight Center, as we celebrate our 20th anniversary. We are rethinking about what we can do, what we can improve, and how to fund it.

One month after the declaration of the pandemic, we had a MOOC about how to cover the pandemic, in a moment that people were desperate. And we reached 9,000 reporters. With the help of UNESCO, we also created a hub. So the future is something like this, which is finding new ways of helping journalists around the world.

Additional Reading

On World Press Freedom Day, Journalism Increasingly Faces Digital and Physical Threats

Editor’s Pick: 2021’s Best Investigative Stories from Latin America

Latin America’s Best Investigative Journalism Featured at COLPIN 2021

Andrea Arzaba is a journalist and GIJN’s Spanish Editor. Arzaba has dedicated her professional life to documenting the stories of people in Latin America and Latinx communities in the US. She holds a Masters in Latin American Studies from Georgetown University, is an IWMF fellow, and part of Transparency International’s Young Journalists Program.

Andrea Arzaba is a journalist and GIJN’s Spanish Editor. Arzaba has dedicated her professional life to documenting the stories of people in Latin America and Latinx communities in the US. She holds a Masters in Latin American Studies from Georgetown University, is an IWMF fellow, and part of Transparency International’s Young Journalists Program.