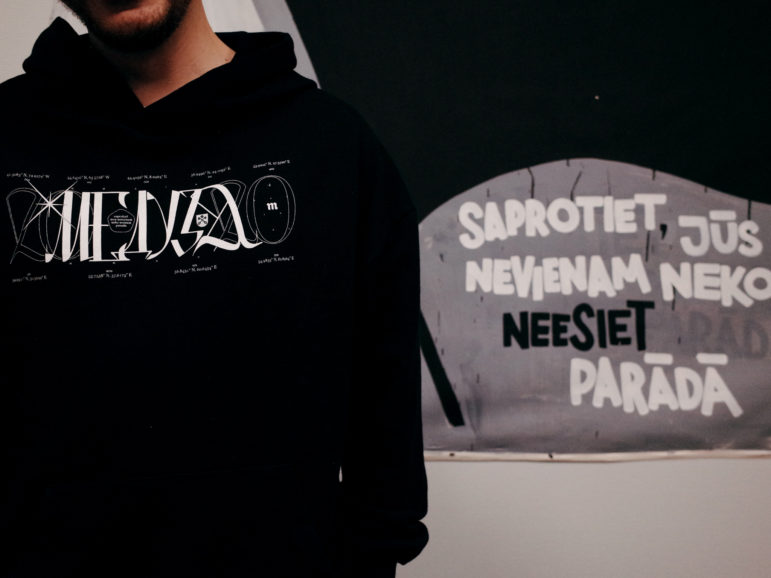

Independent Russian media sites like Meduza are based outside their native country as a result of the Kremlin’s harassment and censorship. Behind the figure — wearing a Meduza hoodie — the text in Latvian reads: “Understand that you don’t owe anyone anything.” Image: Nastya Yarovaya, courtesy of Meduza

Ever since Russia attacked Ukraine in February, almost all remaining independent Russian media outlets and at least 150 journalists have been forced into exile, following a brutal crackdown on free expression and journalism by the Kremlin. Some are operating from rented homes or donated office space in Eastern European capitals like Riga, Vilnius, and Prague, while reporters struggle with residency permits, housing, blocked Russian credit cards, and anxiety.

Exiled media are nothing new. Syrian-Lebanese journalists in Cairo during the late 1800s helped launch the modern Arab press, and the Cold War produced a rich vein of exiled anti-Communist writers. What has changed is the technology, which now enables journalists to better report on their former homelands, and their audiences to better access that reporting.

The free speech community is also rallying in support. In March, Germany’s Schöpflin and Rudolf Augstein foundations – in collaboration with Reporters Without Borders (RSF) – launched the JX Fund, a European fund dedicated to helping exiled independent journalists set up in new locations.

Meanwhile, many ordinary Russians are energetically doing their part to reconnect with banned independent media, with the use of virtual private networks (VPNs) and free censorship circumvention apps skyrocketing since Russia effectively banned independent journalism in March. According to a report by The Washington Post in May — based on data from an analytics company, Apptopia — the daily download rate of the 10 most popular VPNs in Russia rose from around 15,000 before the invasion to a peak of 475,000 in March, and continued at a rate of almost 300,000 per day in early May. (More on some of those apps below). The report added that Kremlin authorities have blocked or restricted more than 1,000 websites since the invasion.

Germany’s Schöpflin and Rudolf Augstein foundations, with Reporters Without Borders, have jointly launched JX Fund, a new fund to support exiled media. Image: Screenshot

Despite having left the country, exiled Russian media continue to face threats of physical surveillance and intimidation via the long arms of Russia’s security agencies. According to The Washington Post, Lithuania’s intelligence service noted increased activity by foreign Russian agents in Vilnius in March, and warned arriving Russian journalists to be alert for harassment and even infiltration by spies in their new home base. In response to the threat from Russia, Vytis Jurkonis, a project director with Freedom House, a pro-democracy nonprofit, warned: “I don’t think the [exiled] journalists should concentrate in any one country.”

Russian media in exile have relocated to several cities like Riga, Vilnius, Prague, and Tbilisi.

Over the years, many displaced journalists have managed to navigate surviving outside their home country with varying degrees of success, especially with the advent of digital distribution channels in the past 15 years. In a series of interviews with GIJN, exiled news leaders offered best practices and lessons learned from their own experiences. This transition, they say, requires having a diverse and adaptable set of distribution channels, deploying smart tactics to preserve your domestic audience and keep your in-country sources safe, collaborating with other newsrooms on everything from shared office space to local banking procedures, and being ready to play a digital “cat-and-mouse” game with native authoritarian governments.

Recent case studies show there is reason for optimism. Radio Free Asia (RFA) – a US government-funded nonprofit – delivers news to six Asian countries where a free press is prohibited, including China, North Korea, Myanmar, and Vietnam. (RFA maintains it has an institutional firewall to protect against editorial influence from the US government.) RFA’s affiliate, BenarNews, also provides uncensored news to an additional five Asian countries.

RFA’s staff was forced to flee Myanmar after the military overthrew the civilian government on February 1, 2021. Despite power outages, targeted blocking of Facebook, and a wider press crackdown by the junta, local website traffic has remained strong, says RFA president Bay Fang, who covered China, Afghanistan, and Iraq for US News and World Report and served as diplomatic correspondent for the Chicago Tribune. RFA’s Myanmar Facebook following has since grown by 25%, including half a million new followers in the week after the coup. RFA data also shows that 76% of its post-coup website traffic inside Myanmar is linked to censorship circumvention technologies like nthLINK and Psiphon.

In a recent webinar hosted by the East-West Center — a Honolulu-based think tank mostly funded by the US government — journalists from Myanmar pointed out that many independent media outlets in Southeast Asia face the same plight as those in Russia and Ukraine. For instance: panelists pointed out that Russian weapons and surveillance equipment were also used to intimidate the media in Myanmar, and that journalists’ bank accounts were routinely frozen by government decree. Soe Myint, editor-in-chief of Myanmar’s independent Mizzima News, said the organization had also set up multiple small newsrooms across the border in Thailand to reduce security threats from Myanmar’s military junta.

In Latin America, investigative journalists Roberto Deniz, Ewald Scharfenberg, Alfredo Meza, and Joseph Poliszuk from Venezuela’s award-winning Armando.info were forced to flee four years ago after being harassed for their coverage of corruption. Today, their team still covers the country working virtually from different locations. Reporters who work for the organization connect from cities such as Bogotá, Madrid, and Miami to discuss upcoming stories and share how their investigations are developing.

Similarly, more than 100 reporters have left Nicaragua since 2018 after independent media houses were shut down and a number of reporters were arrested. While the media landscape inside the country remains complicated, prominent journalists like Carlos Fernando Chamorro, Lucía Pineda Ubau, and Wilfredo Miranda are now working from Costa Rica, continuing their reporting and holding powerful people in their home country to account.

Traditional Reporting Can Work from Exile

RFA showed the newsgathering power that exiled media can have in 2017 when it became the first to reveal a widespread detention program for Uighur Muslims in China’s Xinjiang province. How did they do it? One RFA reporter based in Washington, DC, chose midnight newsroom shifts to handle the time difference, and made about 100 phone calls to primary contacts, and their onward contacts, in Xinjiang every night, according to Fang. Follow-up reporting that dug into strange public service announcements revealed the disturbing plight of the children of detainees who were left without caregivers.

“This is another glimmer of light for media in exile – we are able to do [traditional] reporting from outside,” says Fang. “We are not, by the definition, exile media — but our target audiences are generally in countries where there are authoritarian governments who don’t want our reporting there.”

Joris van Duijne, executive director of GIJN member Radio Zamaneh – an independent, Netherlands-based outlet serving Iranian audiences – says informing the international diaspora of repressed societies can be a potent way to get crucial facts to people within those nations. Word-of-mouth sharing and links from trusted relatives and friends, he notes, can tunnel through domestic propaganda and censorship. And it can be quite successful at evading government information blockades, as two-thirds of Radio Zamaneh’s audience is still located inside Iran. This ability to penetrate the regime’s media curtain, van Duijne says, is thanks to a suite of open source censorship circumvention techniques, and an unusually high level of web savviness among ordinary Iranians.

For van Duijne, the principal challenge is more about trust than technology. “How do you make sure you’re perceived as local media, even though people know you’re based overseas?” he asks. Radio Zamaneh was “born in exile” in 2006, through an initiative of the Dutch parliament, and has since largely migrated from shortwave radio broadcasting to independent online news. “We’re reporting the truth and don’t consider ourselves an opposition – but the Iranian authorities do perceive us that way, and there are efforts to brand us as having a foreign interventionist agenda,” he says. “The audience hasn’t bought that for one second.”

Meydan TV, a Berlin-based independent nonprofit news channel serving the citizens of Azerbaijan, was founded by a dissident journalist and former political prisoner. According to its project head, Matthew Kasper, the outlet briefly attempted to run a bureau in Baku, the Azerbaijani capital, but was forced to close that space when media outlets began to be raided by state security agencies.

“Meydan TV was actually founded in exile, which made the set-up easier – we already had good contacts in Germany, which made German-related paperwork easier for us,” he explains.

Piercing the Veil of Censorship

Fortunately for exiled media groups, there are now a host of digital tools and apps that allow them to stay connected to their audiences back home — despite the best efforts of authoritarian regimes to shut them down. Location-cloaking VPNs and the “onion-routing” Tor browser for audiences – as well as mirroring techniques for news outlets – are increasingly popular and effective tools for working around an anti-free press firewall. For example, total Russian downloads of just one censorship circumvention app, Psiphon, ballooned from 45,000 to over one million in the first three weeks of the war in Ukraine, according to Psiphon senior analyst Keith McManamen. He noted that on just one day in mid-March, Psiphon recorded the usage of 788 terabytes of data from Russia, implying a vast consumption of video by users starving for unfiltered news.

Meanwhile, the CEO of the popular virtual private network service ProtonVPN said Russian use of his company’s encrypted internet access service had grown dramatically since the invasion. He also announced that the company is waiving all fees for Russian users, because they now have no realistic means of paying for Western services.

Circumvention tools recommended by exiled editors include:

- The free Psiphon app for users. The anti-censorship tool recommended by all exiled editors interviewed by GIJN was Psiphon, a free, censorship-circumvention app. It uses almost every website-blocking workaround trick in the book. Available on Android, Windows, and iOS, Psiphon 3 uses free, open source software and a combination of secure servers, encryption, and “obfuscation technologies” to connect users to blocked sites in restricted nations. Users simply download the app, and install the software – but must remember to check the box granting permission for VPN access. Its obfuscation feature involves hiding in plain sight. “It conceals the true nature of the traffic – usually blending into the most common type of traffic going on,” says McManamen. “It does work similar to VPN, the difference being the transport protocols and obfuscation technologies we use, because a VPN is not typically resilient to censorship against itself.” While van Duijne acknowledges Psiphon users could experience slower internet speeds and more exposure to advertising, he says audiences find the free service reliable and easy to use, because no digital skills are needed, and it automatically seeks out secure internet connections. See the Psiphon user guide at this link.

- Website mirroring services designed for investigative outlets. Web “mirrors” protect censored websites by duplicating them on major international servers that autocratic governments are reluctant to block. Reporters Without Borders has helped independent media to stay online in 18 countries with its Operation Collateral Freedom mirroring service. Meanwhile, van Duijne recommends the Virtualroad tool, especially for investigative outlets.“Virtualroad is a very well-known provider that hosts websites for independent media and rights groups,” says van Duijne. “Mirroring is incredibly useful, but it does have a flipside. Mirroring was more static 12 years ago – we just copied our entire website to a different location – but now it involves more automation and security steps. It is important to have DDoS (denial of service) protection in combination with mirroring. We learned that the hard way in 2010 when we were severely disrupted.” Meydan TV’s Kasper agrees that it’s important to educate domestic audiences on site-access technologies, while also minimizing their need to use those technologies on a regular basis. “In our experience, the best way is to work with mirror sites so that people do not need VPNs to access content,” he explains. “But also to produce content that explains how people can use VPNs, etc. so that the audience is informed about the options.”

- Explore sustainable web hosting alternatives, like Greenhost in the Netherlands. “Greenhost understands journalism very well, and also offers DDoS protection,” van Duijne notes. Offering a virtual private server and user-friendly web hosting, Greenhost states that “we play an active role in several projects regarding digital security and human rights.”

- Assess whether users can afford paid-for VPNs. If audiences can afford small fees – but likely won’t have the time or digital skills for setting them up – van Duijne says exile newsrooms can point them to several trusted, easy-to-use options, like Mullvad. “If users cannot pay, it’s important to point them to a range of free options while ignoring others,” he says. “There is an issue of trust and ownership as well. Loads of VPNs are unclear in their ownership – who knows if it is the government blocking you that actually runs the VPN. So, for both free and paid-for VPNs, you need to do some research.”

- Consider circumvention apps as a publishing platform. Van Duijne notes that, for a fee, newsrooms can also create a branded version of Psiphon that shows their content as the landing page on the app. “Zamaneh offers a white label Psiphon client to its users,” he says. “It is branded as Zamaneh and available for free. That’s a great service for your audience, but there are not-insignificant costs involved.”

Strategies for Accessing Blocked Audiences

“Mirroring technology works wonders, but how do you communicate new URLs for your site to your audience — these solutions produce very long URLs,” says van Duijne. “In general, you don’t want to force your audience to have to hunt for you.”

Editors need a toolbox of strategies, including these:

- Consider an “all-of-the-above” plan for sophisticated censorship governments. “Into China, it’s no-holds-barred,” Fang says of RFA’s strategy. “We do medium wave, shortwave, satellite, circumvention, what we call “shorter-shortwave” — where the direction changes very frequently; everything.” When RFA was kicked off multiple FM stations in one country, the team quickly redirected its content for urban areas to channels like Facebook, YouTube, and an RFA app that users downloaded.

- Add a digital access beat to your news content. Several veteran editors in exile say regular public service and even ordinary tech-industry stories on digital safety and web access help to empower audiences with the knowledge they need over time.

- Redirect news to your social media channel while establishing your exile presence. Alexey Kovalev, investigations editor of Russia’s independent Meduza outlet – who fled Moscow for the Latvian capital Riga on March 5 – told the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism that the team focused on news on the war via their Telegram social media channel in the first week of the crackdown. “On Telegram, we went from half a million subscribers to a million just in the last few days,” Kovalev noted. Like Radio Zamaneh, about two-thirds of Meduza’s audience remains domestic.

- Use encrypted document tools for at-risk sources. Kasper says his team at Meydan TV focuses on digital safety for sources and contributors, which, he says, are developed over time. While he says SecureDrop is likely the most secure document transfer tool for at-risk or anonymous sources, he says many others find PGP encryption or Signal easier to use in practice. “The major challenges we face are the repressions on the ground, and trying to keep everyone as safe as possible,” he explains. “There should be policies about digital security for all those working in the team, regardless of where they are located, so they don’t get hacked.”

- Consider a foreign crowdfunding campaign if domestic revenues are blocked. Kovalev told the Reuters Institute that Meduza had lost access to all of its prior domestic donation streams, and, in response, had launched a crowdfunding campaign outside Russia.

- Explore secure, innovative channels to pay stringers. While exiled editors are reluctant to name secure payment methods they use, Fang said: “There are new, non-banking ways of securely and anonymously getting funds to stringers and people that have helped you in these countries; some are really innovative technologies.”

- Boost audience effort with unique content. If you can offer a unique service in addition to truthful reporting – especially, stories in a minority language – domestic audiences will actively seek out the channels and technologies they need to find exile content. “We are the only Uighur language news service, and, because of that exclusivity, we also count on our audience wanting to find our stuff,” says Rohit Mahajan, chief communications officer at RFA. “They know they’ll be getting content that can get nowhere else. We’re actually in nine languages, and our affiliate BenarNews publishes in another five.”

- Preserve some radio transmission capability, if possible. Shortwave radio has a proud history of breaching censorship but has necessarily taken a reduced role for many media organizations. “The problem was the jamming and blocking of shortwave frequencies; it became a game of whack-a-mole for us, and can be expensive to shift frequencies,” van Duijne says. “It also has a discoverability problem, where the audience simply can’t reach you anymore.” However, Fang emphasizes that exile media should not abandon this channel. “This is an argument we’ve had to make: we really need to keep shortwave, even if surveys show only a tiny percentage coming through that channel,” she says. “You still have to maintain it as an insurance policy. Governments can turn off the internet.”

- Invite user-generated content from domestic audiences. Encourage your audience to share their in-country video clips – and highlight encrypted channels like Signal and Protonmail. “A lot of people do let us know about their videos on messaging apps, but encrypted email is definitely the way to go,” says Fang. “We get videos from citizens and then we verify it; we’re very rigorous about that, but this is a way to get information out of a place where reporters can’t be.” Fang says a secure, user-friendly system for sharing tips – provisionally known as “global leaks” – will be rolled out this year.

Van Duijne argues that the time is now ripe for exiled newsrooms to build a global collaborative network.

“A decade ago, there were international programs for exiled media, including needs-based training that was very helpful to us in terms of sustainability,” he says. “To my knowledge, there has been nothing since, and there is no association of exiled media.”

“For one thing, we need it for collective bargaining,” he adds. “Important services from these tech companies and satellite services are relatively expensive for small exile initiatives, so we need a way to coordinate joint subscriptions and strengthen our bargaining position with these companies. We have to know how to help each other.”

Additional Resources

How Armando.info’s Exiled Reporters Keep Reporting on Venezuela

Exiled Journalists Keep Investigating in China, Burundi, Venezuela, Russia, and Turkey

Meet the Exiled Pakistani Journalist Documenting Censorship in South Asian Newsrooms

Rowan Philp is a reporter for GIJN. He was formerly chief reporter for South Africa’s Sunday Times. As a foreign correspondent, he has reported on news, politics, corruption, and conflict from more than two dozen countries around the world.

Rowan Philp is a reporter for GIJN. He was formerly chief reporter for South Africa’s Sunday Times. As a foreign correspondent, he has reported on news, politics, corruption, and conflict from more than two dozen countries around the world.