Premesh Chandran. Photo: Courtesy of the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism.

After 22 years, Malaysiakini co-founder and CEO Premesh Chandran stepped down in February. Malaysiakini is a Malaysian online news site published in Malay, English, Chinese, and Tamil with millions of unique pageviews every day.

Publishing in a restrictive media atmosphere where most of the news platforms are either owned or controlled by the government, Malaysiakini has gained global reputation by remaining independent. This freedom comes from their business model, a 50-50 split between subscriptions and advertising, which many other news organizations hope to replicate in other countries. Malaysiakini does not depend on government advertising.

What began as a five-member operation in 1999 is now a company with 100 employees. Chandran’s two decades at Malaysiakini parallels the most tumultuous and exciting phase of Malaysian politics since its independence in 1957. In this interview, Chandran discusses every milestone in his discernible journey.

Q. What were the conditions that made you start Malaysiakini in 1999?

A. We hoped that we could use the internet to produce independent journalism at the time. Most of the news media were essentially owned or aligned with the ruling party. This is what experts call media capture.

Mahathir [Mohamad], the prime minister at the time, changed the law in a way that the internet would not be censored. So that created a duality in the media space. There was one law for print and broadcast, and another law for the internet. So we took that opportunity and saw whether we could use the internet to publish independent news. We believed that the internet would grow in time.

Back in those days, we didn’t have social media. We didn’t have phones and we all owned dial-up modem sites. So these were very early days of the internet. But we were hoping that this would allow us to pierce through the government-controlled news media and to allow for the flourishing of independent journalism.

Q. What does independent journalism look like in a restrictive environment like Malaysia, where most outlets are owned or controlled by the government?

A. In Malaysia, different political parties influence different outlets. So when we talk about independent media, we just are just saying independent of any ownership agendas. What I mean by this is a media platform run by professional journalists and editors who are really trying to report fair and accurate news. You know, it wasn’t even going so far as investigative journalism, which is another leap and is hard to do. But even just basic, fair reporting of what’s happening in the country, speeches by both government and opposition leaders… Building a kind of a normal public sphere was our first major goal.

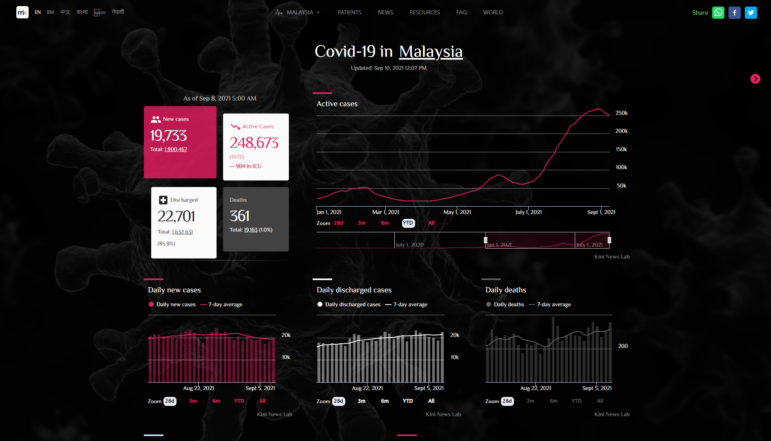

The Malaysiakini COVID-19 dashboard collated data on the impact of the virus in the country. Image: Screenshot

Q. For the first time since independence, Malaysia saw a change in government in 2018. Malaysiakini did great election reporting and announced this change first. Guide us through what happened. How did you manage to do it?

A. We had more people on the ground than our competitors, but we also had strong links to different candidates in different parties. We had a good operating mechanism in terms of knowing how the count was going in different parts of the country. And we were able to collate those results quickly.

The Election Commission would essentially do the count but wouldn’t announce the result. So you kind of know what the count is, but without any official result being declared. By a certain time, it was clear that the opposition had won. But the other outlets, because they are controlled by the government, didn’t want to declare the fact that the opposition had won.

So they essentially held back and waited for the Election Commission to declare the results. But the Election Commission was holding back, so we just declared the result using the unofficial count. And despite tens of millions of people accessing the website, Malaysiakini didn’t go down.

Q. What was the newsroom like on that day?

A. As early as 17:00, polls closed. By 19:30 or 20:00, we got a sense of the electoral results, and around 20:30 or so, the government ordered our site to be blocked. They ordered the telecom companies to block our website so that when someone typed our URL, it wouldn’t point to the right IP address.

Two companies complied and two other companies ignored this order. We had a big dip in traffic. However, we had set up an apparatus to defeat this kind of censorship. So within half an hour or so, the traffic came back. We expected a ton of hostility from the government on that day.

There was a lot of excitement in the newsroom. The minute the government took action [against us] we could see that they were afraid that they’d lost the election. We could see that things were moving very quickly. But the question was whether the government would concede or not. By 23:00 the opposition called on the government to concede. It took a while, but it eventually happened around 2:00 in the morning.

Q. Who are the audiences for Malaysiakini? Have they changed overtime?

A. We have a broad audience because we operate in four languages: English, Malay, Chinese, and Tamil. You have our hardcore political audience who like to follow politics on a daily basis. Then you have your seasonal reader who reads us when something big happens. These are the two main groups.

In terms of geography, Malaysia is very urbanized with 75% of our citizens living in urban areas. Internet coverage reaches about 90% of the population. The internet is by far the number one source of news information for the public as opposed to newspapers or television. The internet reaches more readers than any other media. In that sense, all of those readers are our potential audience.

Q. Many platforms have tried to replicate the business model of Malaysiakini, where subscriptions and advertising account for approximately 50% of the outlet’s revenue, and have been unsuccessful. What is your secret?

A. We launched subscription very early in 2002, nearly 20 years ago. It was a tough journey. The first five, six, seven years, it was very difficult to get subscribers. When people talk about adopting the subscription model, it’s not something that you can do quickly and easily. It’s not like turning on a switch and everything works. You have to be prepared for a decent amount of pain.

We took the plunge early because we had no choice. Due to our [independent] political positioning, we could not rely on advertising. It was very clear that advertisers would steer clear. We had to make a choice between trying subscriptions and being dependent on donor funds, which we didn’t want to. That’s why we went into subscription very early. But only our Chinese and English sections are subscription-based. Our Tamil and Malay sections are free.

We find the right balance between reaching a certain more influential intelligentsia and having a mass readership. You don’t get secured into one niche and have to reach a large audience.

Q. What about the balance between technology and editorial?

A. Many media companies are dominated by an editor or a journalist. They then put a lot of emphasis on editorial. So you have huge newsrooms, but very little technology and sales.

I was a journalist. But I had left journalism and focused on business and technology, and my partner, Steven [Gan, the co-founder], became the editor. Many operations that have been successful have founders who are non-journalists and non-editors. And I think that’s a core part. Technology, advertising, and sales can’t be secondary to the organization. They have to be a very primary element.

One needs to consider that Malaysiakini did not happen in a vacuum. [The country] was going through this process of democratization for the past 20 years. So we basically became the vehicle for a growing demand for democracy. A lot of people subscribe to us to support this idea that we need to move towards democracy and challenge the powers that be. I think it’s not right to just look at it as people buying a subscription. It’s more like people identifying themselves with the mission.

Once you develop trust with your readers, they subscribe because they trust you and believe in you rather than just ‘paying to read the news.’

Q. Now you want to set up a nonprofit so that the platform can continue to remain independent?

A. Yes. We’re setting up the nonprofit at the ownership level. Steven and I are the majority owners and we are not in this for profit. We are mission-based owners. Rather than transferring our ownership to other private hands, we are giving it to a foundation: both the ownership and the governance. But Malaysiakini is commercial. So it’s like the Guardian and other models, where you have a commercial operation but nonprofit ownership like the Scott Trust.

Q. In 2011, when competitor Merdeka Review announced they were going to close, Malaysiakini saved them. You launched a joint subscription package, where a reader would get content from Malaysiakini and Merdeka Review for a single price. This is such a rare show of solidarity in the media world. Can you explain why you did this?

A. Merdeka Review was also an independent news platform in the Chinese language. They were a bit smaller than us, with five or six people. But they ran out of money and they were about to close down.

At that time, our Chinese section was also free. We said: look, why don’t we launch a subscription for both and share the revenue. So we launched a special Chinese subscription package under which you would get the Malaysiakini Chinese and the Merdeka Review Chinese for a very decent price, and we would give them half the revenue, even though we were carrying the load in terms of setting up the subscription system and collecting the money.

The idea was that if we are doing something similar, even though we’re competing, there’s always room for collaboration and making sure the other succeeds. That really brought us a lot of support.

We try to support other outlets who are doing a good job. We are always in solidarity with other organizations, even though they are our direct competitors. It’s just not about Malaysiakini.

Q. Have you ever thought of expanding to other countries like Indonesia or Thailand?

A. We do collaborate with other news organizations in other countries. But we have not expanded because news is a very localized thing and you have a very localized flavor. I don’t think the brand can really expand in that way. And we also have a strong sense of media sovereignty. It’s really about people in that country deciding to do independent news and developing it. There are a lot of organizations coming for training, collaboration, and joint projects. But from an ownership point of view, we’ve never thought about expanding outside Malaysia.

Q. How does Malaysiakini keep up with the tech? For instance, the COVID-19 in Malaysia tracker is fantastic.

A. We were born digital. In the early years of the internet, there was not good software out there. We launched before there were simple things like WordPress and other tools available. We wrote a lot of our own software from the start. Over the years we’ve got a very strong software team and we have our own content management system called News Graph.

We have built a subscription system and we have our own data dashboard. So we’ve built a lot of software over the years and improved on it. We are very tech-savvy and we can build technology quickly. Technology is a core aspect of the organization.

Malaysiakini is built around editorial expertise. We’ve got a strong advertising sales team and we’ve got a strong technology too. These are three key parts of the organization.

Q. Malaysia is now at the cusp of change. Where do you think the country is headed? And what does a free media look like in the country today?

A. Definitely, there is a battle in terms of what Malaysia is about. On the one hand, it can become a more Islamic and more closed society. But it can also move towards a more democratic and a more open society in a more pluralistic sense. Demographically, the Malay and Muslim communities are growing quickly. And that is a huge change.

Many people here also think globalization hasn’t worked. Increasing income inequalities, a sense that the political elite is corrupt… We are seeing very similar tendencies in Malaysia around these topics.

Q. What are you going to do now?

A. I will still be involved in social issues. I’m looking at environmental issues, housing, and other types of issues. So I will kind of stay in this space, explore other opportunities, and let younger people run Malaysiakini. But I still will be in the social space.

Editor’s note: Malaysiakini is a GIJN-member organization and Chandran has served as a consultant for GIJN in the Asia region. This article was originally published by the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism and is republished with permission. You can see the original story here.

Additional Resources

Lessons in Transitioning from Legacy Media to Digital: Expert Tips from Asia

Making Investigative Journalism Sustainable: Malaysiakini’s Steven Gan

After 20 Years Fighting for Democracy, What’s Next for Malaysiakini?

Raksha Kumar is a freelance journalist based in India, whose reporting focuses on human rights, land, and forest rights. Since 2011, she has reported for outlets such as The New York Times, the BBC, the Guardian, TIME, and the South China Morning Post. You can read more of her work here.

Raksha Kumar is a freelance journalist based in India, whose reporting focuses on human rights, land, and forest rights. Since 2011, she has reported for outlets such as The New York Times, the BBC, the Guardian, TIME, and the South China Morning Post. You can read more of her work here.