Pollution flowing from the Amazon basin has spurred huge blooms of sargassum, inundating Caribbean coastlines with rotting banks of the macro-algae. Image: Shutterstock

Journalists are increasingly using the tools of science journalism and scientific inquiry to carry out investigative reporting, and even to shine a spotlight on questionable scientific findings.

Data mining and satellite imagery are often featured in this promising new field of investigative science reporting, which has shown particular promise in uncovering health and environmental stories during this era of the COVID-19 pandemic and of burgeoning impacts from climate change. But Deborah Blum, the director of the Knight Science Journalism Program at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), notes that journalists can use these tools and their skills of “pattern recognition” to draw ground-breaking conclusions on many topics.

“You have many journalists who do data mining — digging into databases and effectively mining information – which is becoming a standard part of good investigative reporting,” Blum says. “The internet actually offers a lot of tools to vet science. When investigating a particular [chemical] compound, for instance, I use PubMed and Google Scholar to vet the science behind every question, and the credibility of sources.”

There are in fact many online databases and other resources that are useful for investigative science journalism. PubMed is a database that contains more than 33 million citations and abstracts of biomedical literature. To name just a few others: the Toxics Release Inventory, run by the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA); Toxic Docs, operated by Columbia University and City College of New York; University of California at San Francisco’s Industry Documents with corporate memos and internal or unpublished reports; and Safety Gate, the European Union’s rapid alert system for dangerous non-food products.

New Tools and Techniques

Meanwhile, Gustavo Faleiros, the Brazil-based founder of InfoAmazonia, a regional environmental news site, is a big advocate of using satellite imagery and other remote sensing techniques to support an investigative science journalism approach known as geojournalism. “Our need to understand the environment has pushed journalists to use earth science, geospatial analysis, all the data from satellites and remote sensors, along with data visualization and interactive mapping tools, to explain the rapid changes we’re seeing,” he says.

These journalism leaders have lots of examples of stories that have been illuminated by investigative science techniques. Faleiros points to a series of stories that InfoAmazonia produced last year in collaboration with Internews’ Earth Journalism Network (EJN) — where I serve as executive director — and other journalists in the Americas on how pollution flowing out from the Amazon basin has spurred huge blooms of sargassum, inundating Caribbean coastlines with rotting banks of the macro-algae.

“Finding the high-resolution satellite imagery – both to document the world’s longest algae bloom and that the mining in Brazil’s Tapajos region was a source for toxic pollution – was very important,” Faleiros explains. “We were able to do this thanks to our partnership with EarthRise Media” — a digital agency that supports environmental reporting with high tech tools.

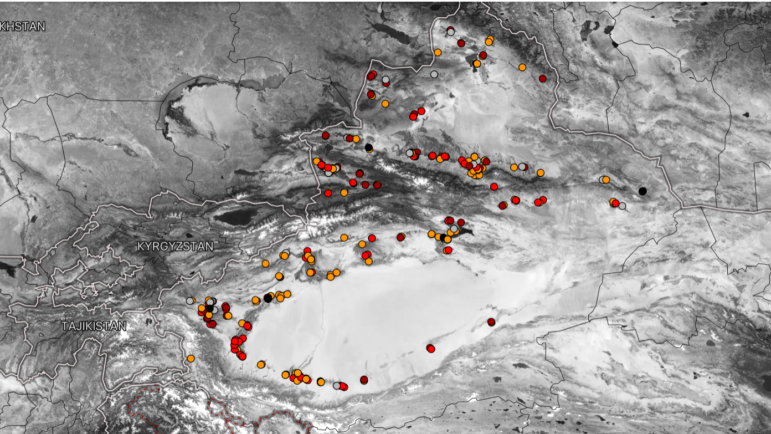

One of the maps used by BuzzFeed news to illustrate an investigation into prison camps in China. Image: Screenshot

These techniques are not only being used for science-related stories, Faleiros notes. The Pulitzer Prize-winning stories from BuzzFeed News on the Uighur camps in China’s Xinjiang province were based on analysis of satellite images and 3D architectural models, revealing their nature as detention centers. Both Google and Bing had blurred these areas on their public maps, so BuzzFeed used imagery from Planet, a for-profit company that provides detailed satellite imagery, to show that the detention camps were more extensive than the Chinese government had acknowledged. “Scientists would not venture to do such research,” he adds.

Faleiros, who now works for the Pulitzer Center’s Rainforest Investigations Network, is also collaborating with Planet and KSAT, a Norwegian firm, to provide training for journalism fellows on how to carry out advanced image analysis and extract measurements using spectroscopic filters that can measure changes in vegetation. EJN, meanwhile, is training journalists in the Mekong region — spanning Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar, Thailand, and Vietnam — on how to use data journalism techniques to improve environmental reporting, and has just published a list of datasets that are useful for environmental and climate-related investigations. Other groups with resources to share include the Society of Environmental Journalists (SEJ), the Association of Health Care Journalists, the Health Journalism Network, Investigative Reporters and Editors, the World Federation of Science Journalists and its national affiliates, and, of course, the Global Investigative Journalism Network.

Blum has also used science journalism techniques to uncover stories and draw important new conclusions, as with her piece for Undark Magazine about the risks of using soy formula to feed babies. “I was trolling around some of the scientific journals, including a couple of papers on soy formula and its effect on the endocrine systems of infants. I started researching the number of estrogens in soy milk and realized, this is a big experiment in human development. No one has tested what it means to give soy formula, which has 11,000 compounds, to infants,” she explains. “I talked to a federal official and asked him point blank, and he agreed we’re essentially conducting an unplanned experiment on children’s health.”

Liza Gross, a reporter with Inside Climate News who was previously a science journalist with PLOS Biology and who specializes in covering climate change and California agriculture, has another example from her own reporting, as she describes here. “People used to think that most harmful pesticides were being applied in the Fresno area, but I managed to obtain data from researchers and a geographic information system (GIS) expert that showed which pesticides are being applied where,” and that dangerous amounts were being applied in Ventura County, which is in California’s agricultural heartland, and near to several schools.

“We can draw conclusions from research and data that scientists haven’t gotten to yet,” claims Gross.

Undark magazine’s The Great Soy Formula Experiment explored the potential health impacts of giving soy milk to children. Image: Shutterstock

Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic

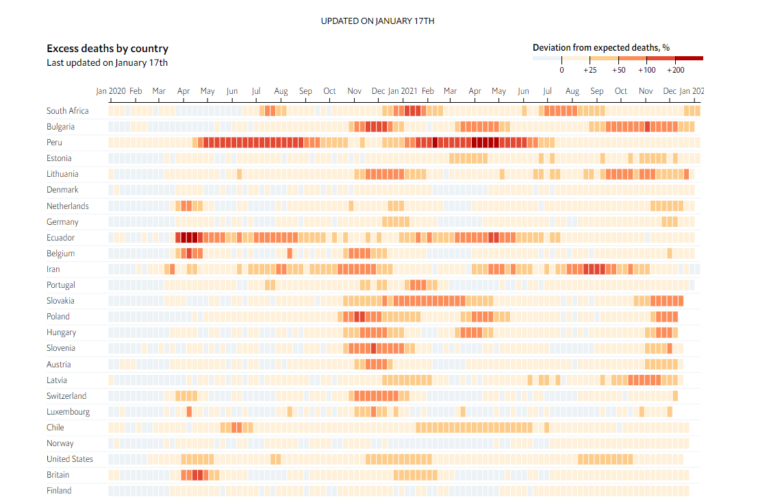

Blum, Faleiros, and Gross all believe that the advent of COVID-19 has greatly spurred on investigative science journalism, as journalists try to piece together data on mortality rates that many governments are either unable to collect or actively seek to obscure. The Economist magazine’s report on excess mortality during the pandemic is a case in point. In Brazil, adds Faleiros, the Folha newspaper is working together with O Globo to try and collect accurate mortality data, as the government’s numbers are not trusted.

The pandemic also offers a good example of how investigative journalism is evolving: to uncover stories and abuses within the scientific enterprise itself. Both Blum and Gross point to the debate about the origin of the COVID-19 virus — whether it originated in a lab, or came from other interactions between people and animals, for instance in a Wuhan wet market – as an example of how journalists need to maintain their skepticism even when scientists and other experts initially suggest the answer is clear.

“Those who were covering COVID were possibly too close to scientists, who originally discounted the lab leak theory, until David Relman at Stanford University said we should look into it,” says Gross.

The Economist’s excess death data tracker. Image: Screenshot

Interrogating Scientists — and Science Itself

“Leon Lederman [the Nobel Prize-winning physicist] noted that everyone used to accept the word of scientists, but now we see more willingness on the part of journalists to question some findings, and we’re seeing pushback from scientists about journalistic coverage, as well,” says Blum. “We shouldn’t be cheerleaders for science. We do independent inquiry, and our loyalty should be to our audiences.”

Blum points to many examples of journalists who have investigated scientific findings, and the ethical behavior of scientists themselves. Among them: Sam Kean, author of the recent book “The Icepick Surgeon”; Azeen Ghorayshi, who has repeatedly exposed cases of sexual harassment by scientists; and going back further, John Crewdson’s investigation of Robert Gallo’s claim to have discovered the HIV virus. Rebecca Skloot’s investigation of the use of cell lines in medical research, as documented in her book “The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks,” is another good example.

Again, there are online resources that journalists can turn to when investigating scientific research and researchers: Ivan Oransky’s Retraction Watch, which provides updates on academic papers that have been retracted, why, and who are the repeat offenders; and Charles Seife’s teaching of science investigation at New York University (NYU). Gross sees an urgent need to monitor more closely the work of governmental scientific agencies, such as, in the US, the Food and Drug Administration and the Environmental Protection Agency.

The effort to meet such needs is coming not just from traditional journalistic enterprises, but increasingly from nonprofit news sites like ProPublica, EJN, China Dialogue, Mongabay, Oxpeckers, InfoNile, the Environmental Reporting Collective, and the funding agencies that support such coverage. “We’re seeing more and more foundations putting money into science journalism in different ways, because of COVID and climate change in particular,” Blum says, pointing to the $20,000 Sharon Begley Science Reporting Award now being given out by the Council for the Advancement of Science Writing as one example.

Gross adds that there are many funding sources for stories focused on scientific research. Among these are the Food and Environmental Reporting Network (FERN), the Fund for Investigative Journalism, Type Investigations, the SEJ Fund For Environmental Journalism, Science magazine’s Fund for Investigative Reporting, and the Alicia Patterson Fellowship. In Europe, the Arcadia Fund has also helped to establish the new Earth Investigations Programme, which is offering grants to journalists around the world.

Blum would still like to see more such efforts, and is a believer that journalists — as observers trained to see patterns in data and events that others may miss — have a lot to contribute when it comes to investigating scientific phenomena and the scientific process itself. “But journalists need to understand the underlying science, and be meticulous about the facts,” she warns.

Faleiros likewise sees the need for deeply informed science journalism. “Particularly when it comes to topics such as health, the environment, and climate change, the phenomena we’re seeing – such as the impacts of the Amazon on South American rainfall or algae blooms in the Atlantic – are increasingly complex and global,” he notes. “That’s why this kind of investigative science journalism is increasingly important.”

Additional Resources

Climate Crisis: Ideas for Investigative Journalists

New Data Tools and Tips for Investigating Climate Change

My Favorite Tools: Geo-Journalist Gustavo Faleiros

James Fahn is the executive director of the Earth Journalism Network at GIJN member Internews. He is also a lecturer at the Graduate School of Journalism at the University of California at Berkeley, where he teaches international environmental reporting.

James Fahn is the executive director of the Earth Journalism Network at GIJN member Internews. He is also a lecturer at the Graduate School of Journalism at the University of California at Berkeley, where he teaches international environmental reporting.