Historical research is essential in a country that buries the dark chapters of its history says journalist Trina Roache. Image: Courtesy of Roache

From deaths in custody to forced displacements to confronting fake tribes: Indigenous journalists are unearthing groundbreaking stories from and for their communities, said Suzanne Dredge, a producer for Australian Broadcasting Corporation Investigations and an Indigenous Wiradjuri woman.

It’s about time, she added, while moderating a panel of leading Indigenous journalists at the 12th Global Investigative Journalism Conference (#GIJC21).

“Indigenous investigations are important — we need more journalists and more media organizations to pay attention to the systemic issues affecting Indigenous communities all over the world,” said Dredge. These journalists’ insights on, and experience with, the structural injustices derived from colonialism are changing the way newsrooms conduct Indigenous investigations.

During the session, three veteran Indigenous reporters in Canada, Australia, and the United States shared their recent work, with some noting how collaboration has made a big difference.

Canada’s ‘Creation Story’

Trina Roache, a member of the Glosscap First Nation and an award-winning Mi’kmaw video journalist in Canada, has spent hour upon hour in archives, looking for clues that help to uncover the country’s past and how it has treated its Indigenous communities,

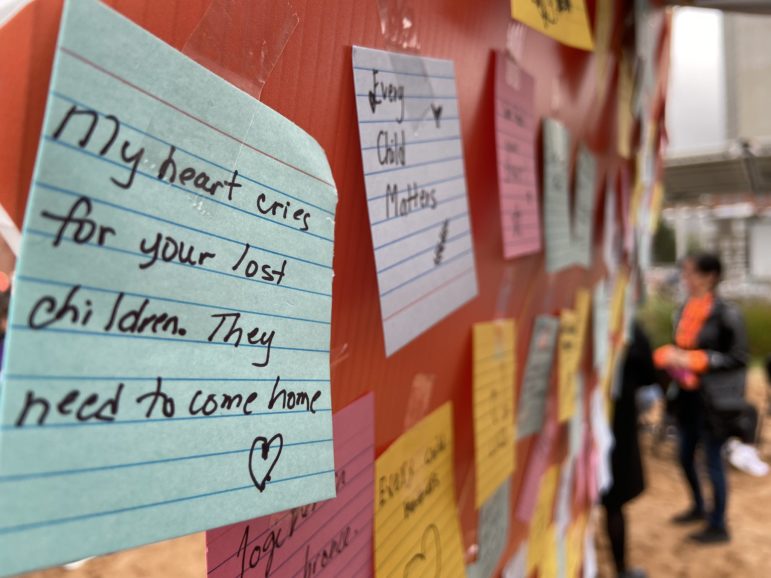

She points to important recent discoveries that led to the uncovering of the unmarked graves of more than a thousand children in the so-called “residential schools,” which operated from 1883 to 1996. They have been described as concentration camps for Indigenous children.

Roache said that historical records are an important source for investigative journalists looking to cover — or rather, uncover — state-sponsored abuses. And they are essential to digging up details on the dark chapters of history a country wants to keep buried, she added.

“Decisions made in the past carry forward to today,” said Roache. “And honestly, Canada has a creation story that distorts reality, especially for Indigenous people.”

Roache’s most recent archival work focused on the long-lasting effects of the forced displacement, or what the department of Indian Affairs called the “centralization” of the Mi’kmaq (plural for Mi’kmaw) during the 1940s. For her story, Uprooted, Roache relied on sources such as the Indian Affairs RG10 records, Library and Archives Canada, parliamentary debates compiled in Hansard, and church records, which were challenging to get because the religious institutions that ran the residential schools usually refused access.

Besides perseverance, especially in the face of mountains of paper, Roache said it’s necessary for reporters to approach archives with very narrow queries. Avoid getting buried, she counseled, adding that these documents only provide part of the story.

“Archival records are words on paper,” she said. “Mainly, we talk to people and they will always put things in perspective.”

Australia’s Database of Injustice

The Australian penitentiary system had stopped counting how many people were dying in custody. The coroner reports showed that many of the prisoners and detainees listed the same cause of death — “medical issues” and “self-harm.” But it appeared that Indigenous people were far more likely to die in custody.

“We knew that something was wrong,” said Lorena Allam, a Gamilaraay and Yuwalaraay woman who is the award-winning Indigenous affairs editor for the Guardian Australia. “When we realized that the data wasn’t being kept, we figured we should do it ourselves.”

Allam’s reporting team spent several months pouring over every available coroner’s report related to Indigenous deaths in custody from 2008 onward. Documents related to the deaths that had not gone to an inquest were compiled and verified, and the cases were assessed against 37 data points. Every non-Indigenous death from 2010 to 2015 was also tracked for comparative analysis.

It all ended up in a database, which became part of the 2018 Deaths Inside project, and led to a series of stories and follow-ups as the data kept growing:

- The team found that more than 474 Aboriginal people have died in custody since 1991.

- A 2020 article added updates and reported that the proportion of Indigenous deaths where medical care was required at some point, but not given, was 38%. The database also showed that deaths increased from 2018 to 2019.

- An update was published delving deeper into the differences between those death-in-custody cases involving the Indigenous and those involving non-Indigenous detainees. For example, they found Indigenous people who died in custody were more likely to not have been charged with a crime.

- A 2021 story offered profiles of some of the Indigenous people who died in custody, and of their families. These victims were specifically chosen, in part, because the families approved using their names and images for the article. Normally, using the names and photographs of the victim violates ancient Indigenous laws since these communities believe it disturbs the deceased’s spirit.

The stories forced the government to establish a taskforce to investigate and sparked protests. It also sparked a national conversation. Even so, Allam expressed anger and frustration that she has covered deaths in custody for 30 years and yet they continue to happen. Still, this is only the beginning of these stories, she said. “Communities expect we will continue to tell the stories that they want told,” she added. “And the incarceration and custodial system in Australia is one of the biggest issues we face.”

A map showing the massacres involving Australia’s Indigenous communities and colonists. Image: Screenshot taken from the University of Newcastle’s “Colonial Frontier Massacres in Australia, 1788-1930” interactive map

The US: Exposing Hidden Stories

In 2019, the Global Investigative Journalism Network brought Indigenous reporters from seven countries to its previous Global Conference (#GIJC11) in Hamburg, Germany. From the group’s meetings emerged an international network of like-minded Indigenous investigative reporters.

Two years later, they broke ground with a story called The Anti-Indigenous Handbook. It involved Indigenous journalists from The Aboriginal Peoples Television Network, the Guardian Australia, High Country News, and the Texas Observer, collaborating with the Indigenous Investigative Collective and the Economic Hardship Reporting Project. The project documented some of the most common ways in which anti-Indigenous organizations and their sympathizers work to undermine Indigenous peoples’ collective rights.

The story detailed how groups in Montana were created to eliminate Indigenous reservations in that state and destroy the Bureau of Indian Affairs through lawsuits and court battles. It illustrated how some majority-white environmental organizations actively push the narrative that Indigenous people are not capable stewards of natural habitats.

BINGO: Reporting in Indian Country Edition is a tool identifying a reliance on tropes or stereotypes while reporting. Image: Native American Journalists Association (NAJA)

“Thanks to support from GIJN, Indigenous reporters from around the globe came together and discussed potential ideas,” recalled Tristan Ahtone, a member of the Kiowa tribe and editor-at-large at Grist. “We realized the story of The Anti-Indigenous Handbook had some common themes relevant to all of our communities.”

Ahtone, who helped organize the GIJN/NAJA Guide for Indigenous Investigative Journalists, contributed to a second collaborative investigation with a different team of Indigenous reporters from Searchlight New Mexico, Indian Country Today, and High Country News. They set out to determine how many Indigenous people had died from COVID-19. At the height of the pandemic, journalists across the US were reporting on high mortality rates among the Navajo, but they were counting deaths only within the reservation’s borders. That meant thousands of fatalities were not accounted for. But getting that information was stymied by officialdom: freedom of information requests in the four US states that straddle the Navajo nation for this information were denied by various government agencies, citing privacy concerns.

“With all four states denying access to public records, we knew the situation actually had nationwide implications,” said Ahtone. “If we couldn’t get records to examine COVID-19’s impact on this region, it would be impossible to extrapolate any useful information that could give a general perspective of how the pandemic affected 576 nations across the US.”

The resulting article published in High Country News was headlined A Broken System: The Number of Indigenous People Who Died from Coronavirus May Never be Known. The story concluded that the “death counts of Indigenous people, no matter how they died, are woefully inaccurate — and correcting that is likely impossible without a unified system for tracking health issues in Native communities, and regulations requiring death certificates to accurately reflect a person’s Indigenous citizenship, race, and ethnicity.”

Another project by Ahtone and High Country News, Land-Grab Universities, revealed how 10.7 million acres were taken from nearly 250 tribes, bands and communities to build universities across the United States. The investigation involved building a custom geodatabase that mapped some 80,000 land parcels in 24 states.

Ahtone said the success of these investigations — or that they even came about at all — underscores how Indigenous stories must involve Indigenous people. “There is no ethical investigative reporting about Indigenous communities without an Indigenous person reporting, photographing, or editing that story,” Ahtone stressed. “I liken it to … an outlet with no Spanish-speakers covering the US-Mexico border.”

Additional Resources

Exposing How US Universities Profited from Indigenous Land

GIJN/NAJA Guide for Indigenous Investigative Journalists

The Indigenous Voices Fighting Disinformation in the Andes and Amazon

Correction: The original version of this story misstated that Roache’s reporting led to the uncovering of unmarked graves of Indigenous children. In fact, the existence of the graves had already been revealed. GIJN regrets the error.