The Pandora Paper leaks have exposed the secret wealth of the global elite but also offered lessons for journalists investigating financial crimes. Image: Pratikxox / Pexels

Financial crimes such as tax evasion, corruption, and embezzlement of government funds are not victimless crimes: They prevent growth in developing economies that need it most. The African Union, for example, estimates that up to $80 billion is lost to corruption every year, and that amount is likely rising.

Investigating these crimes, however, is difficult, time-consuming, costly, and at times dangerous. Journalists digging into corruption are often threatened and harassed, and worse. At the 12th Global Investigative Journalism Conference (#GIJC21), three journalists from the Pandora Papers investigation — thought to have been the biggest collaboration in journalism history — gave advice on covering (and uncovering) these crimes.

The Pandora Papers drew 600 journalists from 117 countries together to dig into 11.9 million documents from 14 offshore service providers, helping to expose the offshore riches of world leaders and politicians, billionaires, and celebrities. While much of the investments, while hidden, were not illegal, many skirted the law while others featured “a global lineup of fugitives, con artists and murderers.”

Here are tips from reporters who worked on this story from Bosnia-Herzegovina, Kenya, and the United States.

- Get your facts straight: The Pandora Papers investigation has continued to ruffle feathers since the stories began to appear in early October. Of course, these pieces elicited howls of outrage and charges of “fake news” by those whose offshore dealings were exposed. The best defense in the face of these attacks is getting your facts straight, said Purity Mukami, data journalist with Finance Uncovered. This will help avoid the appearance of bias. “Always remember that the quality of your investigation will determine the kind of impact it will have on the audience,” she said. Meanwhile, the most important tool is paperwork: Get those financial documents backing up everything you have written.

- Don’t be in a hurry to publish: These stories are not breaking news and shouldn’t be treated as such. Journalists involved in the Pandora Papers leak spent two years studying and sorting files, tracking down sources, and analyzing public records and other documents obtained by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ). They were not in a hurry to publish. Miranda Patrucic, investigative reporter and regional editor with the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP), said it is important to remember that writing takes time. “So, take the time and don’t try to write in a hurry,” she said. “Write. Cut. Rewrite. Cut. Rewrite.”

- Collaboration is key: While investigating the web of offshore companies in Panama and the British Virgin Islands secretly owned by seven members of Kenyan President Uhuru Kenyatta’s family, Mukami didn’t know how to go about analyzing the 20,000 documents containing the data she needed. With collaboration, she was able to create lists from the documents, conduct batch searches, and organize her findings through timelines and diagrams. “Collaboration is key to investigating financial crimes,” Mukami said. “You will always need someone to ask for help about something while working on your project.”

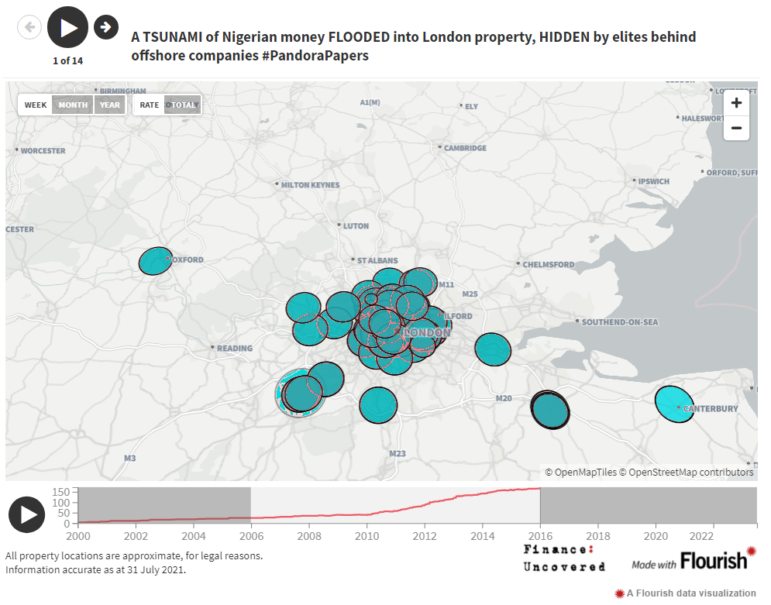

A map showcasing the properties purchased by wealthy and influential Nigerians between 2010 and 2015. Image: Screenshot from Finance Uncovered

- Be security conscious: While it is important to investigate illicit financial deals involving politicians, celebrities, and religious leaders, always remember that no story is worth dying for. Kunda Dixit, publisher of the Nepali Times, said it is critical for reporters to always take measure of their safety and be vigilant while carrying out investigations on financial crimes. After all, some powerful people have a lot to lose if certain secrets are exposed and could act out of desperation. Keep that in mind as you begin probing what many don’t want you to see.

- Understand how these crimes work: You must first understand the crimes to be able to unearth the right information. Scilla Alecci, a reporter and partnership coordinator at ICIJ, said figuring out how the supply chain works and who the enablers are is important. Also, check if the activities involve trusts — a legal arrangement that allows a third party (often a financial service provider) to hold assets on behalf of the beneficiary. “These can be used to hide ownership and to add another layer of ownership secrecy to an already complex structure,” Alecci said. And find out exactly how fraud and money laundering work in specific jurisdictions.

- Persevere: Investigating financial crimes takes a lot of effort and creativity. Sometimes, you have to think like a criminal. “There are various investigative techniques that should be used to begin the process of piercing the veil of secrecy,” said Patrucic. “But there is no formula except to be as creative as the criminal.” That means outgunning the criminals and the weapons of choice are always going to be documents, even though that might require going up against government officials trying to hide them. Also, keep in mind that some of these financial documents can be found in other countries. Outlets like ICIJ have millions of financial statements and records that can help journalists investigating financial crimes with data for their stories they otherwise might not be able to get.

- Stay organized: Drowning in paper? That’s normal for journalists working on financial crime stories. To keep from getting lost, stay organized: Create timelines, summaries, lists, and tables. Make excel your best friend. Create databases. It will help you stay on top of the information and also spot the inconsistencies and the big picture among the data.

Reporters can also check out the money laundering chapter by OCCRP’s Paul Radu in GIJN’s Reporter’s Guide to Organized Crime.