Illustration: Kata Máthé / Remarker

There is simply no substitute: in order to investigate inequality — a critical task, with the pandemic now accelerating the yawning gap between rich and poor — reporters must spend much more time with vulnerable communities.

And they need to focus those investigations on the systems that perpetuate exploitation.

These were the central takeaways from a panel on covering inequality, held online this week at the Global Investigative Journalism Conference. In it, journalists based in three of the world’s most unequal societies — Brazil, South Africa, and the United States — shared tips on how to tackle this global crisis.

According to one recent Oxfam report: “COVID-19 has the potential to increase economic inequality in almost every country at once, the first time this has happened since records began.”

The speakers explained that the reason new tools and resources alone cannot substitute for immersive time in inequitable societies is that — for most journalists — covering inequality requires nothing less than a “paradigm shift.”

For instance, Wendi Thomas — founder of US nonprofit newsroom MLK50: Justice Through Journalism — posed a question shared with her by a teacher: ‘What if poverty isn’t an accident, but a robbery?’ Thomas invited attendees to imagine the collective story power that the investigative journalism community could unleash if poverty was instead seen — as she now views it — as the consequence of systemic theft.

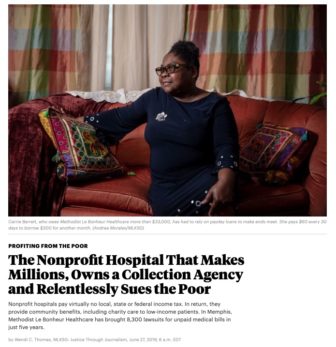

In 2019, Thomas exposed a part of that system in the US state of Tennessee — revealing that one hospital had brought 8,300 lawsuits against its poorest patients for unpaid medical bills in five years. She found that the hospital even sued many of its own minimum wage staff, despite knowing full-well they couldn’t afford those bills — and she realized this brazen greed presented an access opportunity for the data records she needed. With help from ProPublica, Thomas and MLK50 later won financial justice for targeted patients.

Thomas said the best way to start to understand the diverse life experiences of marginalized communities, and improve all coverage of it, is for newsrooms to create real diversity in their editorial staff.

Elaize Farias, co-founder of Amazônia Real, a Brazilian outlet that focuses on Indigenous peoples and human rights, said the most important reporting tool for tackling inequality is humility.

In a comment applicable to covering other vulnerable communities, Farias cautioned journalists not to let their uninformed assumptions color their work. “It’s very important to change all your paradigms about the Amazon region: change your stereotypes; everything you’ve learned from films and news reports,” she said. “We don’t necessarily follow a consumerist approach; the concept of poverty is nuanced — sometimes people don’t see themselves as poor.”

Farias added: “We wanted to give visibility to marginalized groups, and to look at how colonization, racism, and Eurocentrism took shape.”

Moderator Gina Chua, executive editor of Reuters, illustrated the need for this shift with an example of emphasis and story-framing. “A sentence that reads: ‘Black people are often turned down by banks for loans’, versus ‘Banks often deny loans to Black people’ — the first sentence basically says the problem is with Black people, and [implies] we should help them get better at getting loans, and the second sentence says banks are the problem, and how do we fix banks,” explained Chua.

Thomas agreed. “The framing is essential — the first sentence, ‘Black people don’t get loans,’ absolutely obscures the actor,” she said. “The question investigative journalists need to answer is the ‘why’? For instance, framing it on what banks are doing allows you to get at the institutional racism that created these systems where Black people are not getting loans. It’s better to reform systems that talk about interventions with people.”

This sea change, speakers said, also applies to traditional newsroom practices. For instance: why are many editors willing to grant anonymity to powerful executives, but not for the working poor — people with potentially much more to lose through employer retaliation?

In a move she says “should embolden reporters,” Thomas convinced her editor to allow a minimum wage worker to be an anonymous source, and this person’s brave testimony shook-up an exploitative industry.

But to shake-up society itself on the breathtaking scale of modern inequality, you need what one speaker — Johnny Miller — calls “stop-you-in-your-tracks visuals.”

In rare cases, a simple data point can achieve this effect. For instance, in 2017, an investigation by The Boston Globe’s Spotlight team found that while the median net worth of white households in the American city of Boston was $247,500, the median net worth of non-immigrant Black households was just $8. That single-digit figure caused a policy-changing firestorm.

Nonetheless, Miller, founder of a social justice nonprofit, Unequal Scenes, said the impact of large-scale inequality often requires stark visual evidence to move the policymaking needle.

This jarring photo showed the juxtaposition of a São Paulo favela and a luxury highrise. Image: Courtesy of Unequal Scenes.

Using the same drone imaging resources he offers to newsrooms as co-founder of AfricanDRONE — a nonprofit that supports “drones for good” in Africa — Miller has photographed from above the jarring juxtaposition of rich and poor communities in more than two dozen cities, from Mexico City to Mumbai and his long-time base of Cape Town.

While it is hard to show the gulf between a billion dollars and minimum wage in words, Unequal Scenes has prompted renewed conversations about extreme inequality with images of improvised shacks alongside manicured golf courses; yachts next to favelas, and slums crowded around expensive stock exchange buildings.

“I consider drone imagery to be a very democratic technology that can improve people’s lives,” said Miller. “I’m looking at wealth and income, and unequal relationships between the Global South and the Global North — and drone journalists have an important role to play in reporting on inequality.”

However, Miller agreed with the other speakers that research and community trust were the starting points for these stories — and said that reporters need to spend at least a week with vulnerable communities before reporting on the issues they face.

Given the potential disconnect between journalists and marginalized community members, Chua asked the panel how reporters can build that trust.

MLK50’s Thomas ran errands and attended church with sources like Carrie Barrett (seen here) to build trust during an investigation of a hospital suing thousands of poor people. Image: Screenshot

Citing her experience on the hospital investigation, Thomas said she joined sources in their everyday activities — attending church; sharing a commute — and was careful to show these sources paper copies of her prior work.

“They entrusted me with their stories, and I take that trust very seriously,” said Thomas.

Farias said learning Indigenous languages would be ideal, but that the use of local interpreters, and spending off-the-record time with communities, were also important.

“Remember that Indigenous peoples in Brazil have been the object of attacks and threats for more than 500 years,” advised Farias. “Minority and marginalized groups have been treated in a very stereotyped way — in a very folkloric way, where reporters want to give an exotic twist that has nothing to do with reality. So really talk to people who rarely get media coverage.”