Illustration: Kata Máthé/Remarker

Journalists need access in order to do their jobs, and investigative journalists, in particular, often rely on contacts and whistleblowers who expose themselves to a number of potential and actual risks. This is why protecting these sources — or at the bare minimum making them aware of the risks involved in their actions — is crucial.

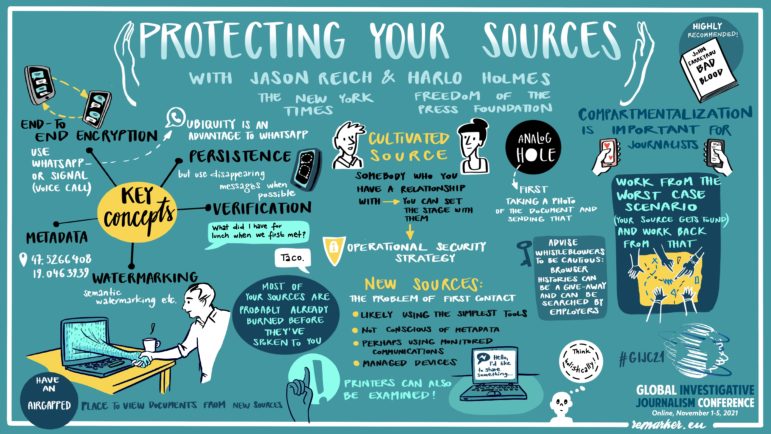

Speaking at a workshop about protecting sources at the 12th Global Investigative Journalism Conference (#GIJC21), Jason Reich, the vice-head of corporate security at The New York Times, advised reporters to categorize their sources into two broad groups. “Cultivated sources” are people journalists have relationships with: friends, family, and contacts who are about to enter a new role as sources, he said. There are also “new sources,” people unknown to the reporter and who are associated with what Reich calls the “problem of first contact.”

“Cultivated sources are much easier,” Reich said. “You can set the stage with them. You can prepare them before they do the things that they are going to do.” He added that most first contact sources have already compromised their digital safety because they might not have security training and not be aware of metadata, which can accidentally give them away.

One cautionary tale of these potential risks involves NSA whistleblower Reality Winner, who left a trail of clues when leaking top secret documents to The Intercept in 2017, leading to her swift arrest and, eventually, a five-year prison sentence.

Regardless of what category a source falls into, Reich and Harlo Holmes, chief information security officer at the Freedom of the Press Foundation, shared tips and tools journalists can deploy in order to keep their sources safe.

Use end-to-end encrypted messaging apps: One key way to protect sources is by ensuring that the information they share with journalists remains private, and this involves using tools that shut out any third-party presence. Messaging apps like Signal and WhatsApp encrypt messages, ensuring that only the devices used by a journalist and the source receive a message in a legible format. The content of these messages is encrypted while being sent over the internet, meaning no one else can read them. This, experts say, is safer than using emails or SMS where the messages are often stored on a server in legible format and corporations can be compelled by law to reveal them.

Reich added that another layer to end-to-end encryption is to use disappearing messages, which delete automatically after a certain period of time. Apps like Signal and WhatsApp have this function.

Have a verification plan: This can be verification of the source or of the message they are sharing with the journalist. It is important to always verify the source before every conversation so that journalists can be sure they are speaking with the same person. “It could be as simple as asking ‘What did I order the first time we met?'” Reich said.

Create an analog hole: Transferring data over the internet is not always safe, particularly if information is being sent over a monitored server. It’s possible that new sources may have already compromised their safety simply by contacting the journalist. In cases like this, journalists should try to mitigate the impact of this outreach. One way to do this is having the source send copies of the document they wish to leak by a more or less “analog” means. Giving an example on how this can be done, Holmes said journalists can ask the source to take a snapshot of a document instead of sending the whole digital copy directly. She added that in doing this, the source must ensure they are not using a monitored phone — that is, a phone given by their company — and that their pictures don’t save automatically in the cloud, like Google photos. These pictures can then be sent using end-to-end encryption messages.

Make them aware of the risks: Most of the time, sources or whistleblowers do not understand the risks they might be taking. Journalists should help them understand this, so they are fully aware of how publication of the information they have given could impact them. Holmes advises journalists to direct their sources to lawyers who can defend them in the case of lawsuits or prosecution.

Consciously choose a communication channel: Having a secure means of communication is another way that journalists can protect their sources. Sometimes, sources use managed devices and are not aware if, or how, their organization monitors the device. Helping them determine the best way to communicate without jeopardizing their own safety is one vital way of building trust with sources. The experts advise journalists to never communicate over SMS or email.