The new, interactive Digital Violence platform, designed by UK-based Forensic Architecture, details attacks on dissidents, journalists, and civil society groups by governments using imported, commercial spyware. Image: Courtesy of Forensic Architecture

In June, the Paris Judicial Court in France indicted four executives from two surveillance companies on charges of complicity in torture in Libya and Egypt, following revelations by journalists about their alleged technology sales to repressive regimes. Reporters with The Wall Street Journal discovered Libya’s imported spy technologies through intrepid foreign correspondence — searching abandoned surveillance headquarters in Tripoli as Muammar al Qaddafi’s regime collapsed — while Olivier Tesquet, a reporter at French newspaper Télérama, scoured export licenses and government contracts to investigate spyware sales to Egypt’s el-Sissi regime.

Both companies involved — Amesys and Nexa Technologies — have denied the charges. But to surveillance watchdogs, the cases highlight the dangers of a global boom in the sale and transfer of digital monitoring and interception technologies, as well as the growing potential for accountability. Around the world, alarm bells are ringing that authoritarian governments are acquiring advanced spyware for repression, and democratic governments are deploying invasive surveillance technologies under the guise of crime reduction, national security, or COVID-19 tracking.

This multi-billion-dollar industry involves dozens of tech firms, complicit governments, and secret deals, with far-reaching consequences for human rights, privacy, and the ability of journalists to protect their confidential sources.

How can investigative reporters find out what particular technologies their governments are buying in the shadowy surveillance market — and whether they’re abusing those digital tools for repression or discrimination?

Image: Shutterstock

Human rights groups have already done significant legwork on the global spread of these technologies. In July, UK-based research agency Forensic Architecture — in partnership with Amnesty International and Citizen Lab — released a powerful interactive tracking tool, called the Digital Violence platform, which maps the sales of the notorious Pegasus spyware to governments around the world. It also connects the deployment of this system — which can secretly extract call, email, and contact data from an infected phone — to digital attacks on civil rights defenders and journalists around the world, and even some of the physical abuses that followed.

In interviews with GIJN, investigative reporters and researchers on the surveillance beat say clues to these procurements are often found in plain sight, despite the secretive nature of the deals. This is partly because of a chronic lack of regulation around surveillance, because private-sector vendors wish to market their products, and, most troubling, because some authoritarian officials believe the sheer awareness of these technologies can lead to the kind of self-censorship they desire.

Some government surveillance procurement agreements are legal, and intended to fight crime; some are illegal, and intended to persecute dissidents and journalists; and some are a combination of these. Regardless, journalists need to know how to assess who has what.

Tesquet’s reporting approach was based on traditional muckraking. Combing through hundreds of pages of transcripts from a 2013 French judicial investigation into spyware sales to Libya, he noticed that one company employee mentioned “Egypt,” and connected that reference to executive email correspondence in the appendix of another report. Tesquet discovered that the company had quietly changed its name, and was allegedly continuing to sell the same spyware system, now rebranded as “Cerebro,” to repressive governments, despite the allegations about its earlier abuse in Libya.

“I understood there was an ongoing business — using this parent company in the United Arab Emirates, they sold to el-Sissi the exact same system they sold to Qaddafi,” Tesquet claims, in an interview with GIJN.

The veteran investigative reporter then found that one French company had applied for export licenses for the sale of interception technologies to a dozen foreign governments. He also obtained copies of procurement contracts, which — helpful for other reporters’ online searches — revealed the kind of language governments use when seeking these surveillance tech deals, with terms like: “The provision of services enabling the implementation of an IP interception system to combat terrorist or other criminal activities.”

To date, corporate accountability for the abuse of surveillance exports has been rare.

Responding to the indictments of the Amesys and Nexa executives, Rasha Abdul Rahim, director of Amnesty Tech at Amnesty International, remarked: “The indictments are unprecedented. When left unchecked, the activities of surveillance companies can facilitate grave human rights violations and repression.”

“A trial would send an important message to companies doing business with authoritarian regimes,” says Tesquet.

Where to Find Clues to Surveillance Deals

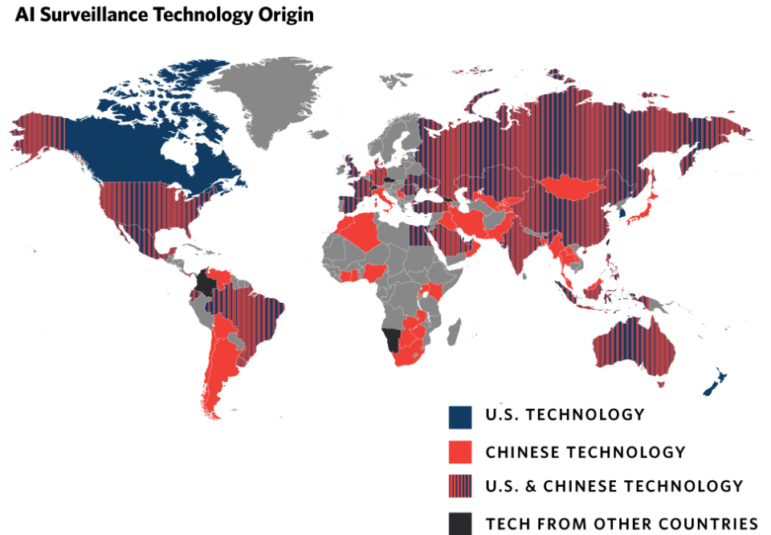

According to the Carnegie AI Global Surveillance Index, at least 75 national governments are actively using AI technologies for mass surveillance. Image: Screenshot

Allie Funk, a senior research analyst at Freedom House, has produced several major reports on digital threats to human rights and accountability, including research that shows how governments exploited the COVID-19 pandemic to monitor their citizens.

Funk suggests reporters look for technologies that fall within four key areas:

- Digital spyware and monitoring tech that allows the user to covertly monitor a target’s communications, or collect personal data emitted from their devices. Funk says these include systems such as Pegasus, Hacking Team, Circles, and cell site simulators known as “stingrays.”

- Technologies that extract data by physically connecting to seized phones — known as “universal forensic extraction devices’’ — such as those developed by Cellebrite. Recently, law enforcement teams in Botswana used this digital tool to search reporters’ phones to try to identify their confidential sources.

- AI-powered surveillance that facilitates mass monitoring — such as Huawei’s “Safe Cities” platforms, and social media surveillance.

- Biometric technologies and facial recognition software, like those used by police to track individuals across New York City in conjunction with a vast array of surveillance cameras.

Surveillance companies broadly insist that their products are sold legally to help governments combat crime. Cellebrite states that its systems help “to protect and save lives, accelerate justice, and ensure data privacy.” NSO Group — which markets the Pegasus system, and which has merged with Bulgaria-based interception tech firm Circles — states that its goal is to “help licensed government agencies… lawfully address the most dangerous issues in today’s world.” China’s Huawei states that its AI surveillance technology cuts crime and improves public safety.

Funk’s tips to find leads on new or abused surveillance capabilities include:

- Comb court transcripts – or interview criminal defense attorneys — in cases where prosecutorial evidence could only have been acquired through digital spying. “Look especially for cases where there’s evidence that an accused had their phone confiscated, and authorities are suspected of abusive surveillance and talk to the attorneys,” she says.

- Flag the international movements of representatives from companies that openly state they only sell their surveillance tech to nation-states. Israel-based NSO Group and its sister company, Bulgaria-based Circles, are two such firms, according to human rights research groups, while others, such as Cellebrite, say they market particular products only to agencies or security research groups. “Ask: ‘What are they in those countries for?’” she says.

- Look out for advanced digital training sessions arranged for law enforcement agencies. Funk says Freedom House discovered that the Bangladeshi government was likely using invasive social media monitoring technology after researchers noticed that the country’s notorious Rapid Action Battalion (RAB) was trained on this in the United States. The report noted that the RAB “is infamous for human rights violations including extrajudicial killings, enforced disappearances, and torture,” and that it was then equipped with $14 million worth of technology to “monitor in real time what it considers to be rumors and propaganda.”

- Speak to private surveillance company representatives at digital trade shows — and track which public officials attend. “Vendors can be surprisingly candid,” she notes.

- In countries with transparency laws, review state budgets and procurement records — or make Freedom of Information (FOI) requests — and closely examine any contract language for digital services. “Look out for vague language, like ‘social media suite,’” she adds.

- Deepen your connections with civil society and activist organizations, and ask them about targeted monitoring of communities. “There are a lot of organizations and researchers who are expertly tracking how these tools are used and by whom,” she notes.

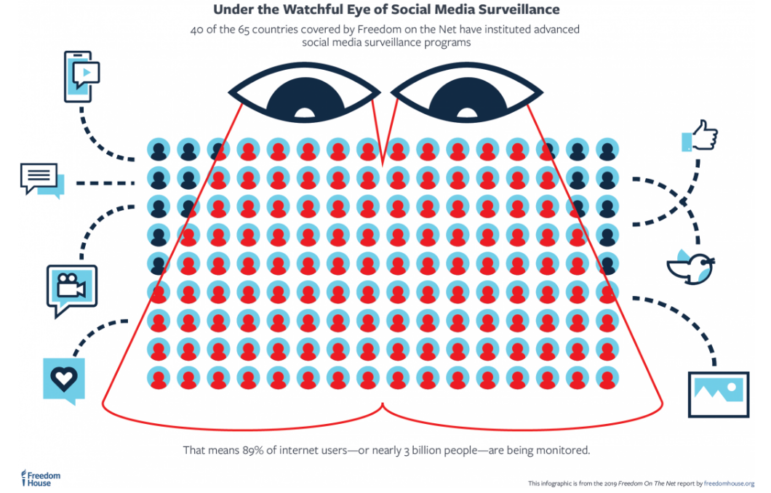

Freedom House found that 40 out of 65 national governments investigated were using advanced social media surveillance tools to monitor citizens. Image: Freedom House

Funk says she is not aware of any comprehensive interactive map of surveillance tools for each country. “I’d love to see one,” she says. However, she advises reporters to start their research by going to the “Countries” page of Freedom House’s annual “Freedom on the Net” report which assesses digital freedom in 65 countries, click on the correct country name, and seek the text under the C4, C5, and C6 categories in the database for a summary.

Crowdsourcing Data on Spy Tech Deployment

A map of law enforcement surveillance technologies does exist for the US — thanks to an Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF) project called the Atlas of Surveillance. The clickable tool includes some 8,000 data points on technologies like aerial drones, automated license plate readers (ALPRs), cell site simulators, and facial recognition software used by some 3,500 law enforcement agencies.

Beryl Lipton — formerly an investigative reporter at the nonprofit news site MuckRock, and now an EFF investigator — says newsrooms in other democratic countries or cities can replicate their own versions of the Atlas.

The Atlas database is built with open source intelligence that is crowdsourced from a network of journalism students and research volunteers, which is then fact-checked. An online tool developed by EFF, called Report Back, sends automated small tasks to volunteers, urging them to search government procurement records, federal grant reports, and news articles for a particular technology in a defined jurisdiction.

“A lot of this information is out there in disparate places, but harvesting it can be a tedious process for a single newsroom, so a targeted way to crowdsource the data is helpful,” she said. “You can just search dot-gov-type sites for the names of major suppliers, like, say, Cellebrite, or keywords, like ‘cell tower,’ which can lead you to further reports. Or you find pitches, where companies have written to say ‘You should consider us, and we would welcome you to get in touch with our existing government customers, who are X and Y.’”

Lipton’s tips for identifying spy gadgetry used by authorities include:

- If your country does not have FOI laws, file freedom of information requests in countries that do. Given the multinational nature of the big surveillance companies — and the prevalence of security cooperation between governments — Lipton says reporters anywhere can potentially find clues about local surveillance technologies by searching public records in countries with freedom of information provisions. Check out GIJN’s guide to using FOI and Right to Information, or RTI laws, around the world, and IRE’s guide to making cross-border FOI requests. “I would love to see more international reporters using US public records, for instance, to figure out what companies that operate in both countries are doing,” she says. Non-US citizens can make US FOI requests, and the same access exists in many other countries. Lipton says references to any overseas training of local law enforcement officers in surveillance methods, in particular, can offer leads about the equipment they will likely use locally.

- Monitor company policies on integrated surveillance products, and look for sources on their internal ethics committees. Lipton notes that a major 2019 announcement by law enforcement supplier Axon (formerly Taser) that the company “will not be commercializing face matching products on our body cameras” — something she applauds as a “good move” — can serve as a guide for investigative inquiry. “That announcement helps to highlight that these companies could integrate facial recognition into body cameras if they wanted to, and others could very well have made different choices or changed their policies,” she adds.

- Ask to see failed procurement bids in FOI requests. “I like to ask for all of the bids in response to surveillance proposals, including materials from the losing bidders,” she says. “You might get lucky because the agency has no particular allegiance to them, and you’ll learn a lot, for instance, about where else that technology was sold.”

Monitoring Law Enforcement Surveillance

But how are these technologies used in the real world?

Image: Screenshot

Jon Fasman, US digital editor at The Economist, recently embedded with police units in the United States and Ecuador to research his book “We See It All: Liberty and Justice in an Age of Perpetual Surveillance.” The book, he stresses, is not anti-technology, but rather pro-democracy and pro-regulation.

Fasman says surveillance technologies are often acquired in democracies for noble reasons, but that their deployment — and the downstream uses of the data they extract — can threaten civil liberties in ways that even their government users might not anticipate.

“Things like ALPRs or Citizen Virtual Patrol [which streams video of city streets to laptops] are not doing anything a police officer couldn’t do in a public space — it’s their ubiquity and ease and invisibility that’s the dangerous part,” Fasman says. “I didn’t witness facial recognition deployed — though I did see some companies that were using it, particularly in Israel. Facial recognition worries me more than tools like stingrays [which mimic cell towers to track phones] because we can leave our phones at home, but we can’t leave our faces at home.”

Fasman hung out in police departments in Newark, New Jersey, and Los Angeles, California, and joined officers on ride-along patrols.

“Cops have ShotSpotter apps on their phones [which send alerts when loud bangs are detected on the street]; in LA, a high ranking officer was really familiar with this predictive policing app,” he explains. “It wasn’t the stereotype of the tech nerd-type explaining to other officers what to do — these were ordinary officers integrating tech into their everyday operations.”

Fasman also embedded with a police department in Ecuador to study how officers used the Chinese-made ECU-911 system, which includes a massive smart camera network and can track citizens’ phones. “What’s striking is that it clearly had a dual purpose — beneficial, because it links up their police, ambulance, and fire responses, but it’s also clear the state could use the system to monitor political dissent in an undesirable way,” he says.

Fasman’s tips for gaining access to surveillance operations include:

- If it’s safe to do so, go ahead and ask police — likely, a public affairs officer — if you can embed with a police unit for a few days. While such a request may be declined in many countries or cities, Fasman says some may agree, as “some departments wish to seem tech-savvy,” and others are convinced that it offers net benefits for the community.

- Log on to any public-access street surveillance system that may exist in your area — such as Newark’s Citizen Virtual Patrol — and spend hours monitoring the same feeds that police watch to get a sense of the privacy issues that arise.

- Be honest in your access request — but not overly candid. “Obviously, you can’t ever lie about what you’re working on because then your word as a journalist is gone,” Fasman notes, but he suggests that you keep your request as vague as possible. “Say ‘I’m writing a piece on how you think about these difficult issues,’ rather than ‘I’m writing a piece on what dangers these technologies pose to our civil liberties.’ Both of these are true, but one will get you in, and one won’t.”

- Seek inside sources or ex-employees for data on “stingrays.” Embedding with police will likely not reveal details on the deployment of “stingrays” — cell site simulators also known as international mobile subscriber identity (IMSI) catchers — as “there is a strict code of silence” about these systems among police departments, according to Fasman. Instead, search public records and look for tips and databases from civil liberties groups — such as this stingray map the ACLU compiled for the US, which identified 75 agencies that own the devices.

How — and When — to Seek Elusive Spyware

Reporters can also anticipate surveillance procurement based on past patterns — such as binge purchases of spy equipment by governments that immediately follow the relaxation of sanctions. The Wall Street Journal investigation of Libya’s spy tech procurement deals noted that “Libya went on a surveillance-gear shopping spree after the international community lifted trade sanctions.”

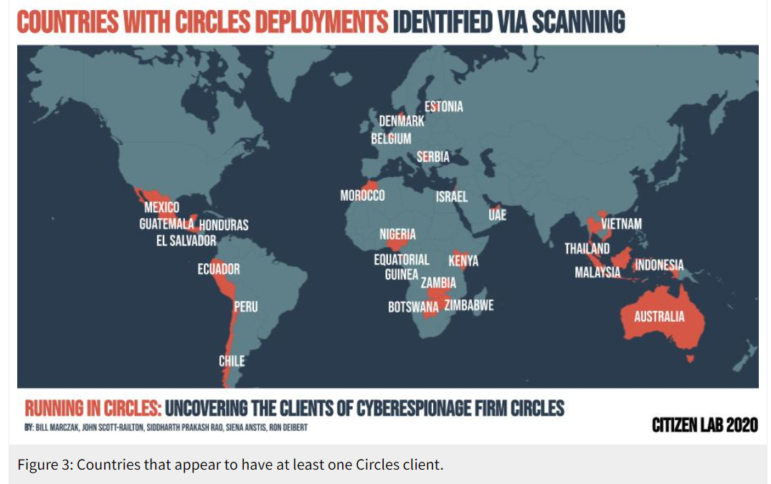

Researchers at Citizen Lab found evidence that at least 25 countries have deployed Circles spyware, which can rapidly locate and intercept mobile phones. Image: Screenshot

Experts say one of the most difficult technologies to detect is the kind that hacks phone communications without hacking the phone itself — especially the Circles system — because it leaves no trace of its intrusion on the phone. Instead, it exploits weaknesses in a common signaling system used to route calls between different telecommunications networks. The software can identify the approximate location of a phone in seconds by causing the home wireless network to believe the phone is roaming, and can reportedly also intercept calls and texts.

Researchers and reporters have generally relied on open source tools and insider tips to detect the government deployment of Circles products.

However, last year, researchers at the University of Toronto’s Citizen Lab found a new method: scanning Internet of Things (IoT) search engines, like Shodan and Censys, for digital firewalls whose hostnames contained a telltale domain name associated with Circles deployments. By searching for the domain name “tracksystem.info,” Citizen Lab identified 25 governments that had purchased Circles systems, and even the particular agencies using them — including many with records of human rights abuses.

Their digital methodology is complex, but they explain in detail, under the “Fingerprinting and Scanning for Circles” section of their “Running in Circles” report.

Human rights group Access Now is currently completing a major investigation into the acquisition of surveillance technologies by governments in Latin America and the Caribbean. Local reporters can watch for the release of that database on the Access Now site in July, or contact their researchers directly.

At the recent RightsCon summit — billed as “the world’s leading conference on human rights in the digital era” — Gaspar Pisanu, Latin America policy manager for Access Now, said sources for the report included FOI requests, interviews, and corporate press releases.

Pisanu told GIJN that LinkedIn had also proved an effective channel for the research and that reporters could use this platform to identify and interview current executives — and particularly recent ex-employees — of surveillance suppliers to governments.

Speaking on the same panel as Pisanu, Thiago Moraes, head councilor of Laboratório de Políticas Públicas e Internet (Laboratory of Public Policy and Internet, or LAPIN), said researchers were surprised to find that many of the costly “surveillance solutions” owned by local authorities in Brazil were not acquired by traditional procurement methods, but were freely donated by foreign companies “as pilot tests.”

Bulelani Jili, a researcher at Harvard’s Department of African and African American Studies, points to a 2019 investigative story by The Wall Street Journal as a key moment in which prior perceptions that “surveillance tech is a Western issue” changed for many civil society organizations in Africa. In this story, reporters found that Chinese technicians were recruited by Ugandan cybersecurity police to hack encrypted communications used by opposition leader Bobi Wine. The investigation alleged that, after unsuccessful attempts by police to hack Wine’s WhatsApp account, software engineers from Uganda’s major digital supplier, Huawei, helped them penetrate Wine’s “Firebase Crew” chat group. Police then stopped planned opposition rallies, and Wine and several supporters were arrested. The Wall Street Journal noted that it “did [not] find that Huawei executives in China knew of, directed, or approved” of any hacking in Uganda, and quoted a company spokesperson as stating that Huawei “has never been engaged in ‘hacking’ activities.”

Jili says journalists can examine the growing number of soft loans — “primarily from China” — that several African governments are using to purchase monitoring technologies.

“Why would a relatively low-income country like Uganda take a $126 million loan from China to then buy a camera surveillance system, particularly when the datasets show no direct correlation with decreased crime?” he asks.

The scope of China’s impact was spelled out last year in testimony by the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace to a US government commission. The think tank found that 13 African governments had acquired advanced Chinese surveillance tech, from Cloudwall facial recognition in Zimbabwe to Huawei’s “Safe Cities” citizen monitoring in Kenya and Uganda.

French journalist Tesquet warns that the field is exploding. “This is,” he says, “just the tip of the iceberg.”

Additional Resources

How Journalists Are Coping with a Heightened Surveillance Threat

The Rapid Rise of Phone Surveillance

Was this story useful? Help us map GIJN’s impact by sharing how you used the information.

Rowan Philp is a reporter for GIJN. He was formerly chief reporter for South Africa’s Sunday Times. As a foreign correspondent, he has reported on news, politics, corruption, and conflict from more than two dozen countries around the world.

Rowan Philp is a reporter for GIJN. He was formerly chief reporter for South Africa’s Sunday Times. As a foreign correspondent, he has reported on news, politics, corruption, and conflict from more than two dozen countries around the world.