Image: Shutterstock

Writing an investigative story in Iraq was never an easy task, but for many years it was at least possible.

During the years following the fall of Saddam Hussein’s regime in 2003, the press in general witnessed much greater freedom than in previous decades, and for years, Iraqi journalists won important Arab and international awards, including many for investigative journalism.

But circumstances changed after the 2018 Iraqi parliamentary elections when the government of Adel Abdul Mahdi came to power, backed by parties that were themselves supported by militia groups. Since then things have become more complicated.

Nowadays, armed factions and influential Shiite, Sunni, and Kurdish politicians, who are generally opposed to reporters covering issues related to their interests, pose obstacles. So, too, with the clans that back corrupt politicians. Then there are those that try to take journalists to court for defamation.

“We can no longer write investigative reports as we did before,” says journalist Saman Noah, director of Network of Iraqi Reporters for Investigative Journalism (NIRIJ). “In the past, we used to write about militias and armed groups outside the state, but now the militias in one way or another have become part of the state.”

He says journalists now fear “direct targeting,” and that investigations into corruption or murder put the lives of journalists at risk.

As a precautionary measure, Noah says his organization uses around six journalists to report each story. Reporters often use pseudonyms, especially if they are based in Iraq. They started using this protective measure around two years ago, but he says there continues to be an exodus of investigative journalists.

“Five journalists who have written investigative stories for NIRIJ are today based outside Iraq and I expect more journalists to leave this year,” he explains. The result? “Iraq is bleeding its investigative journalists.”

From Dictatorship to the Golden Age

Of course, for many years, Iraq suffered under a regime so authoritarian that investigative journalism was unthinkable. The dominance and power of the Baath Party, which ruled Iraq from 1968 until 2003, ensured it was almost impossible to have a free professional media: the press was there to glorify authority and represent the party’s will and agenda. Any real investigative work carried out during the time the Baathists were in power was done overseas, away from the party’s grip.

A handful of supportive news outlets pumped out pro-government content, including a channel launched by the president’s eldest son, Uday Saddam Hussein, who later imposed himself as the head of the Iraqi Journalists Syndicate and set up his own weekly newspaper.

Iraqis were not even allowed to have a satellite device to follow Arab or other international channels; for many years, being found with one could lead to imprisonment or torture.

But the fall of Saddam Hussein in 2003 brought huge changes to all aspects of life in Iraq. In what was to become a golden age for journalism in the country, hundreds of independent newspapers, roughly 100 radio stations, and dozens of satellite channels were launched. Global funding to get these organizations off the ground and to train journalists inside and outside Iraq created a fertile environment for the growth of an independent and objective media landscape.

The journalistic community — and wider Iraqi society — was thirsty for freedom of expression and the freedom to publish and broadcast.

As the money flowed in, new generations of young journalists were trained; grants were awarded to Iraqi media outlets that allowed newspapers, radio stations, and news agencies to report what was happening on the ground.

Investigative journalism was bolstered by the support of Arab Reporters for Investigative Journalism, an Amman, Jordan-based nonprofit organization, which came to Iraq in 2010.

I spent many years investigating Iraq’s armed groups, issues of corruption, and abuses of power. I also interrogated state institutions, and my work helped change parts of the law in one of the areas I was investigating.

This filled me with hope that investigative journalism in Iraq had no limits and that journalists could become truly influential. But the reality today is disappointing.

Investigating Iraq

Iraq has long been a dangerous place for journalists. In fact, it was considered the most dangerous place in the world for reporters for many years.

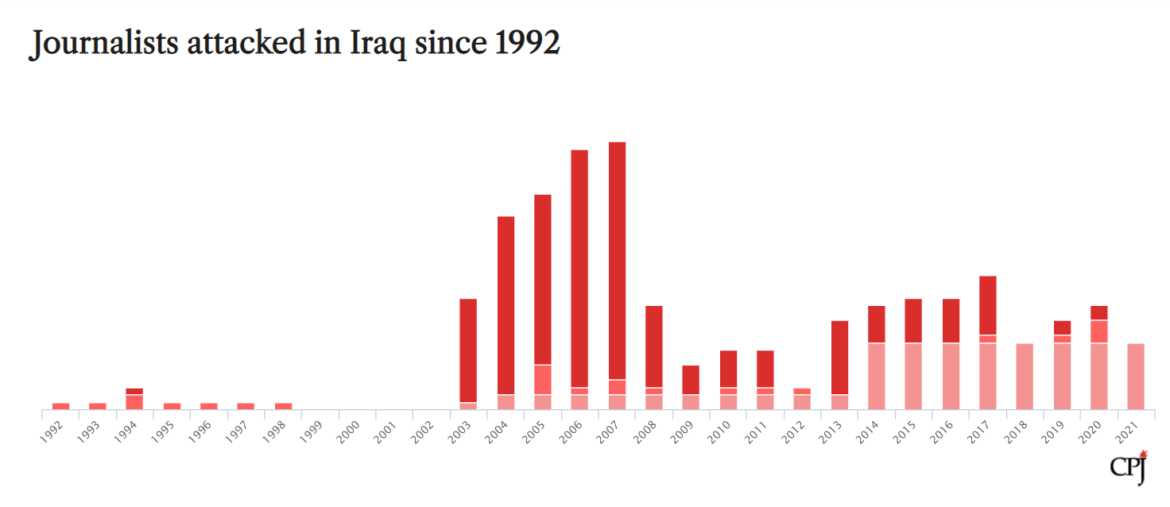

The Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) reports that 190 journalists have been killed in Iraq since 1992. The worst years came after the 2003 invasion of US forces, and during the years that immediately followed, when sectarian violence and fighting between armed groups, al-Qaida, and the remnants of the Baath Party resulted in many journalists being killed as they worked.

The Committee to Protect Journalists records how many journalists have been killed (dark red), imprisoned (orange), or who have gone missing (pink) each year. To give an idea of scale, in 2007 32 journalists were killed, two were imprisoned, and two went missing. Image: Screenshot

The situation calmed slightly during the period following the major American withdrawal of combat forces in 2011, but became difficult again after the emergence of the Islamic State group (ISIS) in 2014, and its occupation of large areas of Iraq and Syria.

Although the recent figures show a decrease in killings (six in 2016, eight in 2017, none in 2018, and then two in 2019 and 2020), these statistics do not tell the full story. While fewer journalists have been killed in recent years, the influence of political money and the weakness of independent media has been tied to high levels of impunity and a panorama of constant threats to journalists. All this has had a chilling effect.

Reporters Without Borders places Iraq at 163 in its press freedom rankings, near Syria (173), and Yemen (169) — out of 180 countries. Even more discouraging is that Iraq has fallen down the rankings each year: in 2013, it was in 150th place.

Freedom House said in a 2020 report that “journalists who do not self-censor can face legal repercussions or violent retaliation,” pinpointing the role of militias that “have shot, arrested, and kidnapped journalists for their work.”

Looking back, the year 2014, which saw the rise of ISIS, was a key moment. The media’s attention focused on how this group had come to occupy a third of Iraq’s territory, leaving thousands of victims and millions of people uprooted and homeless across the country.

During the battle against ISIS, many of Iraq’s warring factions were united against one common enemy. As a result, anti-ISIS militia members enjoyed popular support in the 2018 elections, gaining control of key government parliamentary and ministerial positions. Power was again centralized and talk of administrative and financial corruption — and the growing role of militias — became dangerous once more. And Iraqi society, which was betting on the power of the media to expose corruption, lost the most important thing it gained after 2003: freedom of expression.

Independent journalists have been unable to compete with political money backing more “supportive” outlets. Others found an opportunity to work and live outside Iraq, leaving the arena to media institutions funded by the conflicting parties, armed groups, and political leaders from the north to the far south.

Year after year, investigative journalism became more and more difficult. To dig into certain topics in Iraq today is suicidal. If the reporting corps that is left remains alone and unprotected, at the end of this dark tunnel, there will be no light.

The Arab Spring, and What Came Next

If we compare Iraq with countries like Egypt that saw freedom arrive in the form of the Arab Spring, we can see remarkable similarities.

After decades of rule by a single party under longtime leader Hosni Mubarak, Egypt won its freedom in the revolution of 2011. But it wasn’t to last for long. According to Reporters Without Borders, Egypt currently ranks 166 in a list of 180 countries in the organization’s annual global press freedom ranking. According to Amnesty International, the press in Egypt has experienced a “relentless crackdown” with at least 37 journalists in prison, 20 of them directly in connection to their work.

Journalism in general, and investigative journalism in particular, has suffered massive setbacks. The same is true in Syria, Yemen, Libya, and Iraq. Only Tunisia maintains a relatively stable commitment to press freedom among the countries of the Arab Spring.

In Iraq, the picture remains complicated. Anti-government protests in 2019 led to the deaths of hundreds of demonstrators, while many of the journalists who covered the protests were subjected to persecution and threats from rogue militias and a crackdown by the government.

Anti-government protests in the Iraqi capital Baghdad, in 2019. Image: Shutterstock

There have been changes at the top since then — including resignation of a prime minister. There were high hopes that the new PM, Mustafa al-Kadhimi — a man who spent decades working as a journalist and activist documenting human rights abuses — might bring change, but so far things haven’t improved.

To give a few examples of cases of concern, in March 2020 unknown gunmen abducted journalist Tawfiq al-Tamimi in the capital, Baghdad, while he was on his way to work. He has been missing ever since.

A few months later, in July, unidentified gunmen assassinated Hisham al-Hashemi, a researcher and expert on armed groups. He was killed returning from an interview with a local TV channel. Also in 2020, unknown gunmen killed reporter Ahmed Abdul Samad and photographer Safaa Ghali, as they covered demonstrations in Basra.

After uncovering various corruption cases in Al-Muthanna province, where he lives, journalist Haidar al-Hamdani was threatened, so he and his family fled their hometown. Then, earlier this month, gunmen attempted to assassinate satellite channel reporter Ahmed Hassan, shooting him in the head; he is now in intensive care fighting for his life.

All of the perpetrators of these crimes are still free, despite a government pledge to catch those responsible. The situation is so dire the CPJ ranks Iraq at number 3 in its Global Impunity Index, behind only Somalia and Syria. The ranking, which spotlights countries where journalists are singled out for murder and where their killers go free, lists 21 unsolved journalist murders in Iraq.

As I wrote this article, the lawyer and political analyst Ibrahim Al-Sumaida’i was arrested by Iraqi security forces because of statements he made allegedly insulting public authorities.

Iraqi law as it currently stands imposes strict penalties: life imprisonment or the death penalty for those convicted of insulting the president, parliament, or government, and a seven-year prison sentence for those who insult the courts, the armed forces, public authorities, or government agencies.

Although most of those killed or intimidated in Iraq today are not journalists, these attacks still demand answers. But in this era of general societal intimidation, it has become difficult, if not impossible, for investigative journalists to work under these pressures. Impunity in the cases above has a chilling factor over the press. Instead, silence has become the only way to preserve life.

Additional Resources

GIJN Resource Center: Terrorism Database

Starting Up in Syria: Investigative Journalism in One of the World’s Most Dangerous Countries

Looking for a Suicidal Job? Try Iraqi War Reporter

The writer wrote this piece without a byline due to security concerns. The author is an award-winning, independent journalist from Iraq who has done investigative reporting for over a decade.