Last year geographer Sam Chambers published an unusual map of the Sonoran Desert. He wasn’t interested in marking roads, mountains, and cities. Instead, the University of Arizona researcher wanted to show the distance a young male can walk in various regions of the desert before the high temperature and physical exertion put him at risk of dying from heat exposure or hyperthermia.

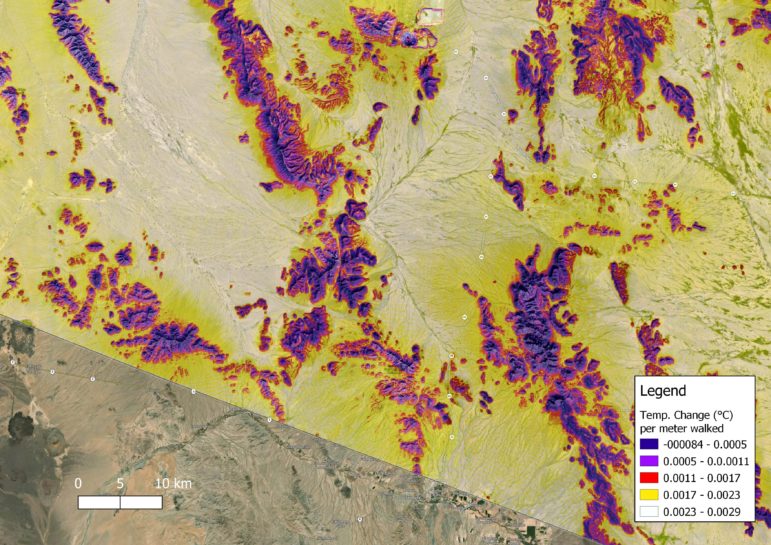

On the resulting map, red and purple correspond with cooler, mountainous terrain. Yellow and white, which dominate the image, indicate a remote, hot valley. It’s here where migrants seeking to cross between Mexico and the United States are at greatest risk of dying from the desert’s relentless sun.

In an email, John Mennell, a public affairs specialist with US Customs and Border Protection (CBP) — the agency that oversees Border Patrol — in Arizona, said that people crossing the border illegally are at risk from the predations of smugglers and criminal organizations, who, he says, encourage migrants to ride on train tops or to shelter in packed houses with limited food and water. Mennell says the agency has installed rescue beacons in the desert, which migrants can use to call for help. According to CBP, Border Patrol rescued roughly 5,000 migrants on the Southwest border from October 2019 through September 2020.

Yet according to data compiled by the nonprofit group Humane Borders, the prevention through deterrence approach has failed to stop migrants from attempting the border crossing. “There continues to be a shift in migration into more remote and difficult areas,” said Geoff Boyce, a geographer at Earlham College in Indiana, and one of Chambers’ collaborators. Migrants have a much higher chance of dying in the desert today than they did 15 years ago, he said, and the numbers continue to rise, from 220 deaths per 100,000 apprehensions in 2016 to 318 deaths per 100,000 apprehensions in 2020. Last year, 227 migrants died in the Pima County Medical Examiner’s jurisdiction, in southern Arizona, although activists say that the number is likely much higher because of the way bodies disappear in the desert.

Chambers and Boyce source mortality data from the Pima County Medical Examiner’s Office. They have gotten information on migrant activity from No More Deaths, one of many humanitarian groups in the Tucson area that maintains desert water and supply stations for migrants. No More Deaths, which supports the decriminalization of undocumented migration, has set up supplies in the mountains and other hard-to-reach areas. Humane Borders also maintains stations in areas accessible by car. These organizations maintain meticulous records — the raw data that launched Chambers’ and Boyce’s first desert mapping collaboration.

Sam Chambers’ unusual map of the Sonoran Desert shows how much the core body temperature of a young man changes for every meter walked. In the white and yellow regions, body temperature increases dangerously fast, while in the mountainous purple and red regions, it is easier to stay cool. Visual: Courtesy of Sam Chambers

On a cool November morning, Rebecca Fowler, administrative manager with Humane Borders, climbed into a truck armed with a list of 53 water stations. She was joined by two volunteers who chatted on the street next to a truck bed bearing yards of hoses and 55-gallon (approximately 200-litre) blue barrels that the organization purchases at a discount from soda companies.

Fowler was leading the Friday morning water run to seven stations off State Route 286, which runs south from Tucson to an isolated border town called Sasabe. Each week, Fowler and her volunteers check to be sure that the water is potable and plentiful. They change out dirty barrels and make notes of any vandalism. (In the past, some of the group’s barrels have been found with bullet holes or with the spigots ripped off.)

Among other data points, Fowler and her team gather data on water usage, footprints, and clothes found near their sites. Using the county’s medical examiner data, they have also created an interactive map of migrant deaths. A search of their website reveals a spread of red dots on the Southwestern United States, so many between Phoenix and Tucson that the map turns black. The organization has charted more than 3,000 deaths in the past two decades.

In her years in the desert, Fowler has noticed the same kind of changes pointed to in Boyce’s and Chambers’ research. “Migrants have been increasingly funneled into more desolate, unforgiving areas,” she said.

GIS modeling, which is broadly defined as any technique that allows cartographers to spatially analyze data and landscapes, has evolved alongside computers. The US military was an early developer and adopter of this technology, using it to understand terrain and plan operations. In those early days, few activists or academics possessed the skills or the access needed to use GIS, said Cinnamon. But in the last decade, more universities have embraced GIS as part of their curricula and the technology has become more readily available.

Now, the kind of GIS modeling employed by Chambers, who uses ArcGIS and QGIS software, is commonplace in archaeology and landscape design. It allows modelers to understand how factors like terrain, weather, and man-made features influence the way people move through a given physical environment.

An architect might employ GIS technology to decide where to put sidewalks on a college campus, for example. Chambers used these techniques to study elk migration during his doctoral studies at the University of Arizona. But after Boyce connected him to No More Deaths, he started using his skills to study human migration.

No More Deaths tracks data at their water stations, too — including acts of vandalism, which they asked Boyce and Chambers to assist in analyzing via GIS. That report, released in 2018, spatially examines the time of year and location of the vandalism and uses its results to postulate that Border Patrol agents are primarily responsible, while acknowledging that rogue actors, such as hunters and members of militia groups, may contribute as well. (CBP did not respond to questions on water station vandalism.)

When Boyce and Chambers finished analyzing the information, they asked themselves: What else could this data reveal? Previous attempts to understand the desert’s hostility had relied on the prevalence of human remains or statistics on capture by Border Patrol agents, but both of those are imperfect measures.

“It’s very hard to get any type of reliable, robust information about undocumented migration, particularly in remote desert areas,” said Boyce. “The people who are involved, their behavior is not being methodically recorded by any state actor.”

Most of the water stations on Fowler’s route were set back from the highway, off bumpy roads where mesquite scraped the truck. By 11 a.m., heavy-bellied clouds had rolled in and the temperature was in the 80s Fahrenheit (above 26 Celsius) and rising. The fingers of saguaro cacti pointed at the sky and at the Quinlan Mountains jutting over the horizon; on the other side lay the Tohono O’odham Nation. Fowler says Border Patrol’s policies increasingly shunt migrants into treacherous lands within the reservation.

Humane Borders’ water barrels are marked by long poles capped by tattered blue flags, fluttering above the brush. Each barrel features a combination lock, preventing vandals from opening the barrel and pouring anything inside. Each is also marked by a Virgin of Guadalupe sticker, a symbol for migrants passing through the desert.

A water barrel strategically positioned for migrants crossing the Arizonan desert. Image: Laura Dixon

At each stop, Fowler and that day’s volunteers, Lauren Kilpatrick and Isaiah Ortiz, pulled off the lock and checked the water for particulates and pH levels. They picked up nearby trash and kept an eye out for footprints. At the third station, the water harbored visible black dots — an early sign of algae — so the group dumped all 55 gallons and set up a new barrel. At a later station, Fowler found a spigot that had been wrenched off and flung among the mesquite. Later still, the group came upon a barrel full of decaying, abandoned backpacks.

This was the third water run for Kilpatrick and Ortiz, a couple from Nevada now living in Arizona. Kilpatrick had read books and listened to podcasts about the borderlands, and Ortiz had wanted to get involved because the crisis felt personal to him — some of his family are immigrants, some of his friends and their relatives undocumented.

“I just think about their journey — some of them are from Central America and Mexico,” he said. “Their lives were in real danger coming through areas like this.”

GIS modeling simplifies this complex landscape into a grid. To analyze the grid, Chambers uses a standard modeling software; so far, he has published five papers with Boyce about the desert. For the first they worked on together, the team took No More Deaths’ data on visits to water sites from 2012 to 2015 and looked at changes in water usage at each site. Once they’d determined which routes had fallen out of favor and which had risen in popularity, they looked at whether those newer routes were more treacherous, using a ruggedness index that Chambers developed with his colleagues by looking at the slope and jaggedness of terrain, along with vegetation cover and temperature. They concluded that official United States policy is increasingly shunting migrants into more rugged areas.

From CBP’s perspective, “walking through remote inhospitable terrain is only one of many dangers illegal immigrants face during their dangerous journey into the United States,” said Mennell. And installing new technology and increased patrol on popular migration routes is actually a good thing, he says, because it contributes to the goal of securing the border against smugglers shepherding in so-called “illegal immigrants.”

In another paper, Chambers studied whether migrants took new routes to avoid increased surveillance, and whether those new routes put them at higher risk of heat exposure and hyperthermia. To map out which areas were toughest to cross — as measured by caloric expenditure — Chambers factored in such variables as slope, terrain, and average human weight and walking speed, borrowing both military and archaeological formulas to measure the energy expenditures of different routes. He used viewshed analysis, which tells a mapmaker which areas are visible from a certain point — say, from a surveillance tower — and, using his slope calculations and the formulas, compared the energy costs of walking within sight of the towers versus staying out of sight.

Chambers tested his findings against the maps of recovered human remains in the area before and after increased surveillance. To map risk of heat exposure, Chambers used formulas from sports medicine professionals, military physicians, and physiologists, and charted them onto the desert. And he found, just as with the ruggedness index, that people are taking longer, more intense routes to avoid the towers. Now they need more calories to survive the desert, and they’re at higher risk of dying from heat.

Caloric expenditure studies had been done before in other contexts, said Chambers. But until this map, no one had ever created a detailed spatial representation of locations where the landscape and high temperatures are deadliest for the human body.

Mapping Migration Globally

Inner tubes of car tires and life vests floating in the Mediterranean sea, used by a boat of refugees for flotation. Image: Shutterstock

GIS mapping is also being used to track migration into Europe. Lorenzo Pezzani, a lecturer in forensic architecture at Goldsmiths, University of London, works with artists, scientists, NGOs, and politicians to map what they see as human rights violations in the Mediterranean Sea.

Compared with the group conducting research in Arizona, Pezzani and his team are at a distinct disadvantage. If a body drops into the sea, it’s unlikely to be recovered. There’s just not as much data to study, says Pezzani. So he and his team study discrete disasters, and then they extrapolate from there.

Pezzani disseminates his group’s work through a project called Forensic Oceanography, a collaborative research effort consisting of maps, visualizations, and reports, which has appeared in art museums. In 2018, information gathered through their visualizations was submitted to the European Court of Human Rights as evidence showing the Italian government’s role in migrant drowning deaths.

The goal is to make migrant deaths in the Mediterranean more visible and to challenge the governmental narrative that, like the deaths in the Sonoran, these deaths are unavoidable and faultless. Deaths from shipwrecks, for example, are generally blamed on the criminal networks of human traffickers, said Pezzani. He wants to show that the conditions that draw migrants into dangerous waters are the result of “specific political decisions that have been taken by southern European states and by the European Union.”

Pezzani, Chambers, and Boyce all intend for their work to foster discussion about government policy on immigration and borderlands. Boyce, for one, wants the US government to rethink its policy of “prevention through deterrence” and to demilitarize the border. He believes the current policy is doomed to fail and is inhumane because it does not tackle the underlying issues that cause people to try to migrate in the first place. Ryan Burns, a visiting scholar at University of California, Berkeley, said he wants to see more research like this. “We need more scientists who are saying, ‘We can produce knowledge that is sound, that is actionable, that has a very well-established rigor to it, but is also politically motivated,’” Burns said.

Cinnamon said that GIS, by its nature, tends to involve approaching a project with a viewpoint already in mind. “If the US government decided to do the same study, they might approach it from a very different perspective,” he said. As long as the authors are overt about their viewpoints, Cinnamon sees no issue.

Burns, however, did sound one cautionary note. By drawing attention to illegal crossings, he said, researchers “could be endangering people who are taking these paths.” In other words, making a crisis more visible can be politically powerful, but it can also have unintended consequences.

Before their last water station visit, the group from Humane Borders drove into Sasabe. A helicopter chopped overhead, probably surveilling for migrants, Fowler said. Border Patrol vehicles roamed the streets, as they do throughout this part of the country.

Once, Fowler said, a 12-foot wall spread for miles across the mountains here. In recent months, it’s been replaced by the US government’s latest effort to stop migrants from venturing into the desert: a 30-footer, made of steel slats, undulating through the town and across the mountains in either direction. It’s yet another factor to consider when mapping the Sonoran and envisioning how its natural and man-made obstacles will shape its migration routes.

“There’s so much speculation” about what will happen to migrants because of this wall, said Fowler. She suspects they will cross through the Tohono O’odham Nation, where there’s no wall. But they won’t have access to water dropped by Humane Borders. “What I worry about, obviously, is more people dying,” said Fowler. She’s certain the migrants “will continue to come.”

Chambers and Boyce plan to keep making maps. They recently published a paper showing the stress that internal border checkpoints place on migrants crossing the desert, the latest step in their quest to create empirical evidence for the increasing treacherousness of the border.

“It’s an important thing for people to know,” said Boyce.

Additional Reading

How They Did It: Collaborating Across a Continent on Latin America’s Untold Migrant Stories

GIJN Resource Center: Migration Reporting

Using Geospatial Technology during a Pandemic

This article was originally published by Undark, a nonprofit digital magazine exploring the intersection of science and society. The original post is here, and this story is republished with permission.

Emily Cataneo is a journalist and fiction writer whose work has been published in Slate, NPR, the Boston Globe, and Atlas Obscura, among other publications. Since becoming a freelancer, she has reported on stories on three different continents and around the United States. She is based in Raleigh, North Carolina.

Emily Cataneo is a journalist and fiction writer whose work has been published in Slate, NPR, the Boston Globe, and Atlas Obscura, among other publications. Since becoming a freelancer, she has reported on stories on three different continents and around the United States. She is based in Raleigh, North Carolina.