Avec l'autorisation d'Elie Guckert.

Realizing the connections: French journalist Elie Guckert. Image: Courtesy

For GIJN’s series on journalists’ favorite tools, we spoke with Elie Guckert, a French freelance journalist who focuses on far right groups and armed conflict, and who contributes articles to sites including Mediapart and Bellingcat.

In November, Guckert and two colleagues revealed how a French charity built close ties with Christian militias in Syria that support President Bashar al-Assad, and provided aid that was ultimately used by warlords who are accused of war crimes.

Guckert says advanced open source tools are increasingly being used to track neo-Nazis and other right wing extremists, and points to a Mediapart story investigated by his colleague, Sébastien Bourdon, which used a variety of tools to identify 50 extremists within the French armed forces.

However, Guckert says his own investigations “tend to be low-tech” — relying on emerging open source tools for geolocation in particular, but which otherwise focus on methods tailored to the characteristic behavior of far-right groups.

Ironically, he says the source he found most useful in determining the true intentions of far right groups is their own propaganda.

“It seems counter-intuitive, but propaganda can give you good information,” he says. “With far right groups, you have to read what they are saying in right-wing sites and propaganda newspapers, because this is where they are speaking truthfully about what they are actually doing. For the Syria investigation, we found an article on the Sputnik news site in Russia where the [French charity] clearly states that they are giving food ‘to those who fight,’ which is itself a violation of humanitarian principles.”

During a search on Instagram for the Syrian story, Guckert found images of the wedding of a senior member of the French charity, which showed both the son of a militia warlord and a soldier in the pro-Assad National Defence Forces (NDF) militia among the guests. Another image shows the director general of the charity — which was founded by two far-right French activists in 2013 — reviewing a militia artillery position in western Syria.

“Of course, it is not a crime to be far-right,” Guckert notes. “This makes these groups confident in their communications about things like finances. But then you have situations like January 6 at the US Capitol, where real crimes do occur. One technique we use is to reach former members of these groups on LinkedIn — not the big fish — where we are careful to just start with general questions, saying we’re just interested to know more.”

He says journalists can also gather crowdsourced leads and databases from anti-hate speech activist groups, like Sleeping Giants. While the goal of these activists is to pressure companies into removing ads from the extremist channels and websites they find, Guckert says reporters can focus on the output of the sites themselves, and their followers.

Guckert’s favorite tools include:

Liveuamap

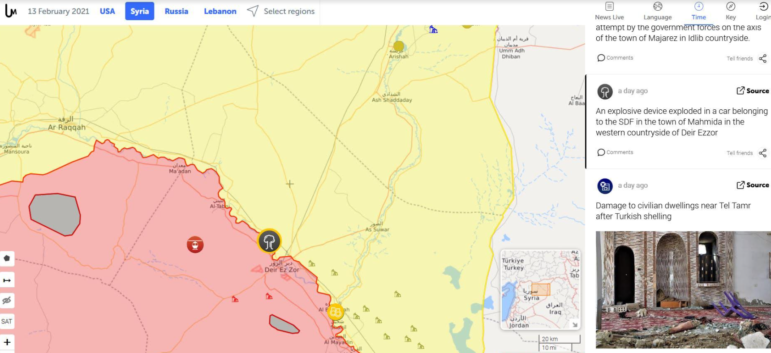

“One tool interesting for geolocation is Liveuamap,” Guckert says, about the site whose acronym stands for Live Universal Awareness Map. “With a subscription, you are able to see the evolution of military front lines over the years. You can use it for places like Syria and Ukraine. And there is a place where people can report incidents on the map — like ‘on this day, a suicide bomb was planted there, and there were three casualties,’ etc. Most of these are sourced. This helped me check claims made by the [NDF] militia about being attacked; about [supposed] war crimes that turned out to be just people shooting back.”

“Liveuamap gives access to the whole history with this kind of incident from 2016 to now,” he adds. “It’s very useful when you need to work on under-reported issues. In the free version, you just have incident reports for a few months. If you want to go years before, you have to pay something like $15.”

Capture d'écran

A map of one Syrian region on the Liveuamap tool. Guckert says the maps often include crowdsourced incident reports, like those seen on the right. Image: Screenshot

Wikimapia

“This is kind of a mix between Google Maps and Wikipedia,” Guckert explains. “If you go to an unknown town on Google Maps, you will not have much information, but, with Wikimapia, a lot of people are giving information — this place is a church, this is a mosque, etc. When you add testimony and photos to this kind of information, you can reach a conclusion.”

Activist Groups

“For instance, Sleeping Giants is a citizens’ movement fighting against hate online by cutting advertising resources for far-right groups,” Guckert notes. “If you look past the activism part, you realize they are kind of doing journalism work, in gathering the kind of information we can use. Their contributors spend entire days capturing messages on Telegram channels and far-right websites. You can speak with their researchers about the data they collect.”

Google Earth Pro

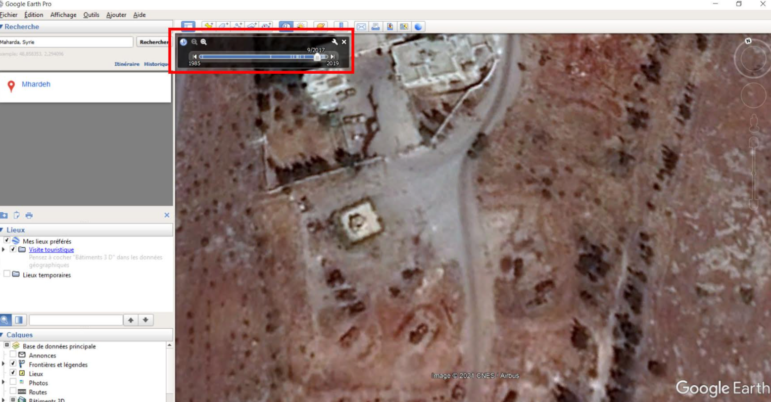

“I am a big fan of geolocation,” Guckert says. “One of the simple questions we asked was: ‘Are Christian militias in Syria positioning artillery near churches?’ I spent a few days trying to find one particular church. There is a simple tool on Google Earth Pro where you click on a ‘watch’ icon, and it gives you a bar with different dates. You move the bar and it lets you travel through time and see changes at that site. This showed heavy armored vehicles stationed near this church.”

Capture d'écran

Entrenched positions for armored military vehicles outside the Syrian monastery in this Google Earth Pro image show how pro-Assad militia used this church as a “propaganda shield,” according to Guckert. He used the tool’s time bar (highlighted) to illustrate how the militia stationed artillery around this religious site. Image: Screenshot

“Patient Scrolling” on Social Media

Despite the availability of reverse-image tools like Yandex and facial recognition apps like Pimeyes, Guckert says “patient scrolling” through social media has brought his best results.

“I spent entire afternoons scrolling down on Facebook and Instagram for the Syria story,” he recounts. “Look, maybe [with] facial recognition software, we could have found images faster, but human knowledge was effective, because we knew the main characters. One day I stopped on a photo and said, ‘This is the chief of the militia!’ — and if you looked at the date and place, I realized all the connections.”

Additional Resources

Tips for Investigating Far-Right Groups around the World

Exporting Intolerance: How the Christian Right Is Funding Political Causes Overseas (Webinar)

My Favorite Tools 2020: Top Investigative Journalists Tell Us What They’re Using

Rowan Philp is a reporter for GIJN. He was formerly chief reporter for South Africa’s Sunday Times. As a foreign correspondent, he has reported on news, politics, corruption, and conflict from more than two dozen countries around the world.

Rowan Philp is a reporter for GIJN. He was formerly chief reporter for South Africa’s Sunday Times. As a foreign correspondent, he has reported on news, politics, corruption, and conflict from more than two dozen countries around the world.