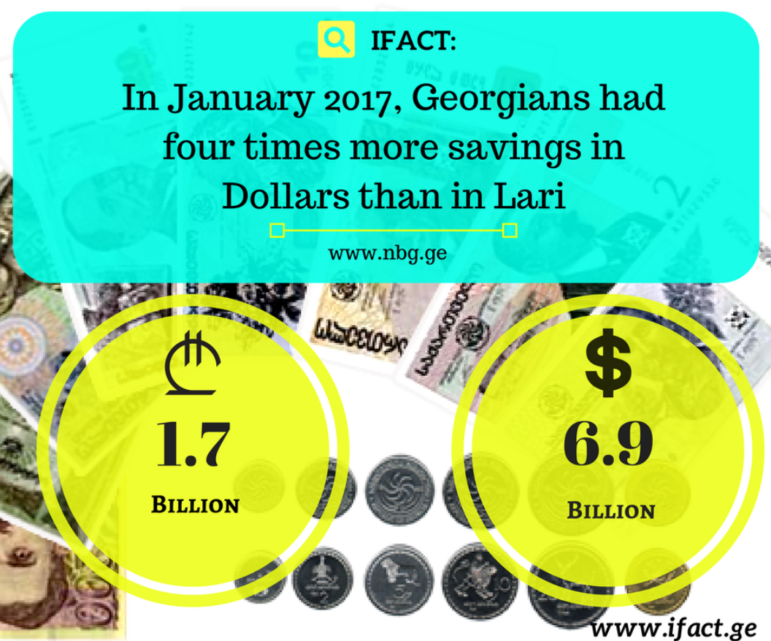

Graphic: iFact

When Nino Bakradze was growing up in Georgia in the ’90s, the country was embroiled in a civil war and a post-USSR economic crisis.

Back then, the country of nearly 4 million in the South Caucasus had just become independent after decades of Soviet rule. The media landscape was dominated by state TV. Investigative journalism just didn’t happen.

Twenty years later, when Bakradze graduated from journalism school, this small country bordered by Russia, Turkey, Armenia, and Azerbaijan had become more progressive; it was regarded as the most European Union-oriented country in the region. But the state of investigative journalism was largely unchanged.

While online investigative media outlets were flourishing in the rest of the world, they were limited in Georgia. Digital media in the country was scarce and underdeveloped, and people in rural areas still got their news from state TV.

To bridge the gap, Bakradze founded iFact in 2016 with fellow journalist Nino Gagua. The two met at the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP), where Bakradze worked after graduating from the Georgian Institute of Public Affairs At the time, she says, Studio Monitor, which was founded in 2005, was producing the most noteworthy investigations as video documentaries. It was the editors at OCCRP that encouraged the co-founders and consulted them on the first steps of forming their own group.

Georgia sits at the intersection of Eastern Europe and Western Asia, in the Caucasus region. Credit: Wikipedia.

Soon, iFact found its first donor — the Open Society Georgia Foundation (OSGF). The organization already knew Bakradze from her work on the Panama Papers and committed to supporting the project. With that funding, the then 26-year-old Bakradze and her 30-year-old co-founder were able to get a couple of other journalists on the team and get to work.

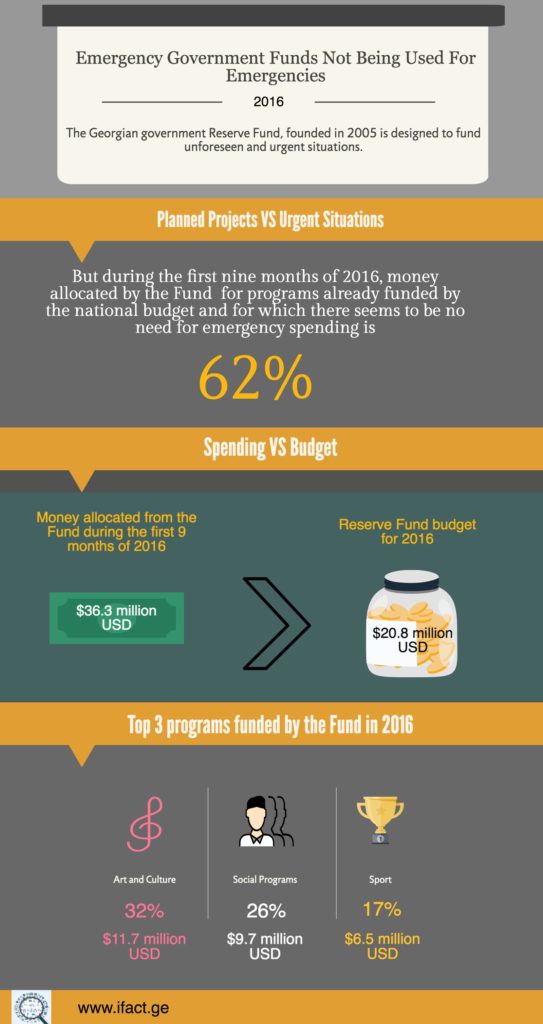

In their first big investigation, they revealed that 62% of national reserve money — which should only have been spent on emergency projects — was used for other projects in 2016. The ball was rolling. In 2020, iFact was admitted to the Global Investigative Journalism Network as its first member in Georgia.

Graphic: iFact

Funding Investigative Journalism

iFact’s funding overwhelmingly comes from grants — including support from the National Endowment for Democracy, OSGF, Prague Civil Society, Internews, the Friedrich Naumann Foundation, and USAID, which together provide 99.5% of their running costs. Individual donors account for the remaining funds.

The team is currently trying to implement a subscription model, but setting that up involves technical difficulties, and they have struggled to find in-country specialists who could help them. Another issue is that raising funding from readers through subscription or crowdfunding is tough in a country where the population is used to everything being provided by the state.

“People have a very, very strong Soviet memory, and [in that period] information was free of charge — because there was no information,” explains Bakradze. “So people have this habit that they get information for free, and they don’t think that they should pay.”

In a good year, iFact’s yearly budget amounts to $90,000-$100,000. Most of this covers staff salaries, transportation costs — which shot up during the pandemic when Georgia went into lockdown and public transport was shut down — and software used for investigations, such as LexisNexis. As of today, the team is made up of 12 people: eight reporters, an editor (Bakradze), an accountant, a media manager, and a designer.

As a way of diversifying its funding, the organization launched the first crowdfunding project in Georgia, for an investigation into the national education system. So far, the team has managed to raise about $140, which, although modest, was enough for them to hire a social media specialist to help improve their content and reach more people.

“We want people here to realize that they need journalists and they should pay for them,” says Nanuka Bregadze, a reporter at iFact since 2017. “But for now, in our society, it’s hard and it’s kind of long term. But you need to start from something, and we started it.”

Meanwhile, to help address the gaps in investigative training in the country, which mostly takes place on the job, iFact started up a program for its staff as well as other journalists — an effort which is funded by partner organizations.

The iFact team in their office in Kutaisi, Georgia. Image: Courtesy iFact

Media Landscape

Georgia ranks 60 out of 180 countries in the Reporters Without Borders Press Freedom Index — higher than its regional neighbors. Compared to Azerbaijan or Russia, it is easier for journalists to work, but there are still challenges. “Azerbaijani journalists who want to carry out investigations were coming here to Georgia because they felt safer here — but now they have started to go to Europe,” notes Bregadze.

“Some topics we are covering, such as church-related stories and stories about Russian propaganda, are extremely sensitive for some parts of our society,” she adds. “Mostly, they are far-right, ultranationalist groups who don’t share the values of the liberal western world, and who want friendly relations with Russia because of religion.”

To prevent any aggressive behavior towards its reporters, iFact sometimes avoids specific bylines in stories.

Another downside, the team says, is that investigations sometimes fail to find pick-up, meaning the government feels safe to ignore the media — and especially the investigative corps.

But the absence of public reaction is a problem, too.

“Sometimes you have no reaction at all — neither from society, nor from government — and for investigative journalists who work on the story for three, four, or 12 months, it’s a disaster when you get no public attention,” says Bakradze.

On top of that, in recent years the level of disinformation and fake news in the country has soared — another method Bakradze believes the government is using to diminish the power of the media. “The propaganda works very well,” she says. “They try to get people as confused as possible. They make the understanding of reality as weak as possible.”

iFact and other investigative media outlets haven’t faced physical reprisals lately. The last notable incident was the 2012 plundering of the office of investigative newsroom Studio Monitor, in which all of its equipment and computers were taken. There is no overt pressure from authorities; in fact, the government mostly ignores investigations into its actions.

But while some of iFact’s investigations might be met with official silence, the group’s work is appreciated in the region.

“iFact has been an incredibly important and a much-needed addition to the media space in Georgia,” says Natalia Antelava, co-founder and editor-in-chief of Coda Story, an investigative media outlet based in New York and the Georgian capital of Tbilisi. “It is a proper investigative outlet that takes on some of the toughest subjects and does them thoroughly. You can see their impact reverberate through the rest of the media and the society.”

To counter misinformation, iFact has another tool: fact checking.

“The mainstream media is [made up of] TV stations — unfortunately, so far, they are very politically biased,” says Bakradze. “And they spread information which is not fact-checked, and sometimes which isn’t reality as well. So they lie to their audience. And then people think that that’s journalism. We have a very serious problem [with] media literacy here.”

To work on the issue, iFact started sharing “infograms” — short visual snippets featuring key facts — on social media. “People liked them, sometimes more than our investigations; these very long pieces,” says Bakradze.

The publication — which is largely published online but has some print products — is based in Tbilisi, and has started expanding. Thanks to funding from the Dutch embassy, it recently opened another office in Kutaisi, a city of about 135,000 west of the capital.

“I love working in the regions, because you see the result of your work better there,” says Bakradze.

And despite officials’ efforts to ignore iFact’s work, some stories have had a major impact. In one of its biggest scoops, the team uncovered a pro-government disinformation network online. After its journalists flagged about 40 Facebook pages, 30 groups, and 18 webpages — publishing fake claims about a controversial oligarch’s supposed donations to battle COVID-19 — all of them were shut down.

In another notable success, an investigation in the Svaneti region revealed that a local government official won a tender through a company registered in his mother’s name. The story caused outrage among locals and, eventually, the official was fired.

During the country’s parliamentary elections in October 2020, iFact conducted an ambitious ballot-counting project to check whether the numbers reported by the government were correct. For a whole week, iFact reporters, their family, and friends counted ballots, eventually finding that 26% of polling stations didn’t count votes correctly.

Participants being trained in the basics of investigative journalism in a program organized by iFact in Tusheti, Georgia. Image: Courtesy iFact

Stories about corruption don’t often garner the kind of attention that other stories do. While the country has seen positive developments in fighting the issue in recent years, it is still a problem; Georgia ranked 45 out of 180 countries in the 2020 Transparency International Corruption Perception index.

But getting that message across through in their reporting can be difficult for the iFact team.

“Our society is very nihilistic. They don’t care about corruption, for instance,” Bakradze says. “If you tell them that they have polluted air, that is a more sensitive issue than stealing millions from the budget.”

Additional Reading

A Ukrainian Investigative News Team Fights for Media Freedom

The Teenage Investigative Reporters Taking on Corruption in Kyrgyzstan

Editor’s Pick: 2020’s Best Investigative Stories in Russian and Ukrainian

Alexandra Tyan is a multimedia journalist based in Paris. . Originally from Moscow, she has worked for Coda Story and for French television, and her work has been published by the Guardian, The Calvert Journal, franceinfo, and The Moscow Times. She speaks Russian, English, French, and Italian.

Alexandra Tyan is a multimedia journalist based in Paris. . Originally from Moscow, she has worked for Coda Story and for French television, and her work has been published by the Guardian, The Calvert Journal, franceinfo, and The Moscow Times. She speaks Russian, English, French, and Italian.