The Continent, a publication out of South Africa, is using Whatsapp to get their content to their audience across Africa.

In 2019, the city of Salvador in Bahia, Brazil, got a new saint: Irmã Dulce, a Brazilian Catholic Franciscan sister, Nobel Peace Prize nominee, and founder of one of the largest philanthropic hospitals in Brazil. During the ceremonial events in Vatican City, a member of the crowd, who had traveled from Brazil to Italy for the canonization, found a familiar face: a journalist from her local news outlet Correio who had been introduced to her via its WhatsApp group.

“She sent a photo of them together to the group and said, ‘He’s very interesting, intelligent, and I love Correio,’” recalls the newspaper’s digital content coordinator, Wladmir Pinheiro. He says this was a perfect example of the personal connection and deeper relationships the newsroom is building with audiences via WhatsApp.

Regional title Correio hails from the northeastern Brazilian state of Bahia. It has a daily circulation of 35,000 and 18 million page views a month online. The newspaper has been experimenting with WhatsApp since 2014. Initially, it used it to get user-generated content, but few messages included a story worth pursuing. Then it started an experiment by building a community around football, with a journalist acting as “a friend and specialist” to share updates and insights within a group.

“We wanted to test how people behave, whether people see value in it, and how easy it would be for us to operate,” explains journalist Juan Torres, who used a Google form on Correio’s website to sign up 50 members to join its original football WhatsApp group.

Why WhatsApp?

By using WhatsApp, Correio is responding to a national trend: In 2019, one forecast proclaimed Brazil as the app’s second largest market after India, with 99 million monthly active users. Other estimates put this estimated audience at 120 million.

The trend goes beyond Brazil, though. Research suggests WhatsApp is most frequently used by people in countries in Latin America and Africa, presenting an important opportunity for emerging, digital-first titles and smaller newsrooms looking for ways to expand their distribution.

Messaging apps are increasingly important for publishers. According to the 2020 Digital News Report, more than half of the people surveyed (51%) said they used “some kind of open or closed online group to connect, share information, or take part in a local support network.” In Brazil specifically, WhatsApp ranked first in terms of social media platform use (83%). Up to 48% of Brazilians use it for news.

How Correio Uses WhatsApp

Correio currently operates 10 WhatsApp groups. At the moment, all are focused on general news, with five initially launched to cover coronavirus. WhatsApp restricts groups to a limit of 256 members, so some groups share the same updates with different subscriber lists. Previously, groups have focused on specific news events or topics likely to attract an invested community, from marathon running to Carnaval.

“We changed how we think about social media with WhatsApp,” says Torres. “Lots of publishers use WhatsApp and chat apps just to distribute content. It’s like fishing to see if you can drive traffic to your website. This isn’t the way social media works. It’s trying to force social media to meet our aims as publishers.”

The newspaper uses WhatsApp’s group function, not broadcast lists. It currently has 10 groups in operation. Five only allow posting from an admin, while the other five are open to members posting. Groups launched in relation to specific events or news stories have been opened and closed over the years. The original football community is still alive but no longer managed by Correio, for example.

“We use the open groups as a source to know what people are talking about and sharing,” says Pinheiro. “We don’t mind if competitors’ content is shared. If it’s just Correio, you make the group feel artificial.”

A small team manages posting, typically adding 10 updates on a weekday, and monitoring conversations in the open groups and chat messages sent directly to admins, which can spark story ideas. Moderation has never been a problem, despite initial concerns. The description sets the tone and the purpose of the group. They only removed a member from a COVID-19 focused group for sharing misinformation. The member was extremely apologetic when informed via a direct chat.

“We act as a trusted member,” says Torres. Group members don’t want to be the only person shouting in a group of more than 200 people, he adds, if that’s not the expectation that’s been set. Establishing this dynamic early and having admins who are regularly present is crucial, agrees Pinheiro.

Traffic from WhatsApp sharing accounts for between 7% and 10% of Correio’s daily audience, putting WhatsApp as its third largest traffic source, behind direct traffic and Google. Yet WhatsApp isn’t about clicks but engagement. Right now this means interacting with around 2,000 highly engaged audience members.

“Our WhatsApp members show more engagement than those who come to the website,” says Torres. “It’s about learning to tell stories that are appropriate for different platforms. WhatsApp has reminded us that we have to put the user at the center.”

Texting in Zimbabwe

Putting the audience first has always been a focus for Zimbabwean outlet 263chat. It evolved from a discussion forum on Twitter in 2012 to a news website and daily e-paper delivered via WhatsApp as a PDF. The e-paper features domestic, business, and international news sections as well as classified listings. The tone of the reports is that of a traditional newspaper, but the design focuses on a mobile audience with one article per page that’s typically 300-400 words or less.

“We’ve looked at how traditional media has worked and reverse-engineered it,” explains Nigel Mugamu, founder, CEO, and “chief storyteller” of 263chat. “I’m always thinking about the end users and how they would want to receive the news.”

In 2014, WhatsApp was growing in Zimbabwe and local mobile networks started shifting their promotions for cheap data bundles to access Twitter, and to packages enabling lower cost data to use WhatsApp. 263Chat started using the app to share links within groups. By 2016, internet penetration in Zimbabwe was higher than in many African countries. For many, “WhatsApp was the internet,” says Mugamu.

Like Correio, 263Chat started to create different editorial products tailored for different platforms and launched a weekly e-paper designed for WhatsApp. They accelerated the project right after the so-called “coup not coup” in Zimbabwe in 2017, when the country’s military deposed President Mugabe while insisting it was not a coup. News was moving so fast that a weekly e-paper was in danger of being out of date very soon. So 263Chat started to release an edition every evening — now at 20:00 local time.

“263Chat came into the market to disrupt,” Mugamu says. “Our thinking is, ‘Why wait until tomorrow to get today’s news?’ That’s what mainstream media does.’”

263Chat’s Twitter presence helped create a strong community of advocates. These were the first recipients of the e-paper and were encouraged to share it with their friends and families on WhatsApp. The product now has 44,500 direct subscribers in around 200 WhatsApp groups. About 15% live outside Zimbabwe.

The next step for 263Chat is an SMS version of their product, an important opportunity to pursue its mission by extending its reach into communities without internet access. “We’ve got a website for those who have access to the internet,” Mugamu says. “We’ve got the e-paper for those who have limited internet access. Soon, an SMS product will take into account those who don’t have any internet but at least have a mobile phone.”

Reaching populations without internet access, including rural communities, is crucial to challenging political corruption.

“These guys [politicians and government officials] can dismiss people on the internet by saying it’s mainly the diaspora,” he says. “But when you start informing people in rural areas about what is going on, we empower people to know the truth. So next time they go and vote, they are aware.”

A Newspaper on Your Phone

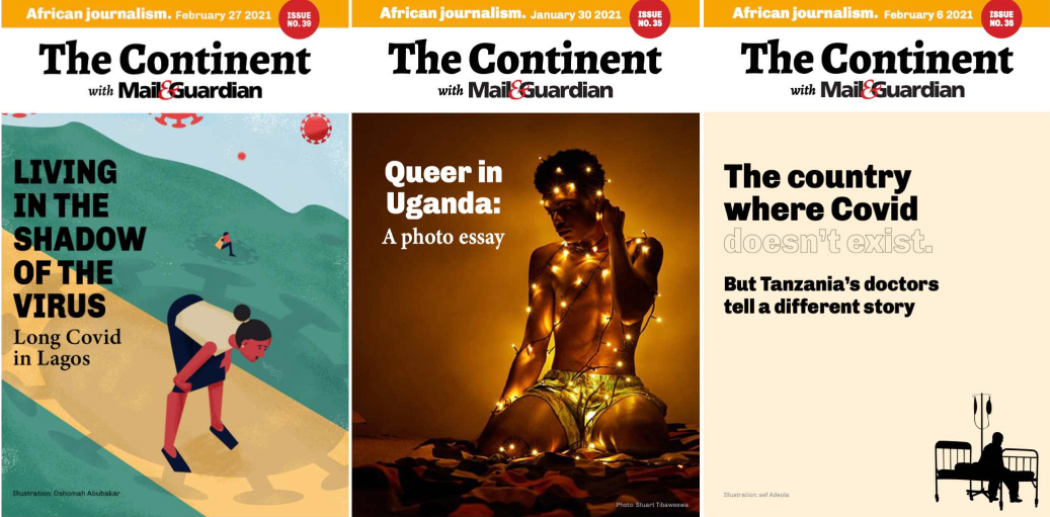

The potential of messaging apps to engage an existing but under-served audience prompted the launch of a similar paper in April 2020. The Continent is a pan-African, PDF e-paper designed specifically for WhatsApp and shared every three weeks.

The costs and difficulties of distributing such a print product have always been an inhibiting factor. Other pan-African titles have typically been produced outside the continent, printed in Paris or London, and flown into African capitals. Simon Allison, editor of The Continent and Mail & Guardian’s Africa editor, realized that messaging apps could be part of the answer.

“Most of the people we know are getting their information from WhatsApp and yet there’s no major media house in our vicinity that is putting information there,” Allison says.

According to the 2020 Digital News Report, WhatsApp was more used in South Africa than any other platform (88%) and it was the second-most used for news (49%) after Facebook (57%). “There’s a disconnect,” Allison says. “As journalists, we aren’t meeting our audience where they are, and they’re not necessarily on websites, on Facebook, on Twitter. We had to figure out a way to reach them.”

COVID-19 was the final push. “We realized the pandemic was an international story,” he says. “It needed a bigger overview, with journalists in South Africa talking to their counterparts in other countries and putting those findings in a place where we weren’t just reaching South African audiences.”

Currently operating with a skeleton team, around 70% of The Continent is based on original commissions published alongside some Mail & Guardian journalism through an editorial partnership.

Size Matters

The nature of the format means that design and story length are paramount to keeping readers engaged. “Our longest edition generated the lowest number of new subscribers,” says Allison. “So we tried the radical opposite in the next edition: lots of pictures, text at its bare minimum, news stories at 250 words, and long-form at 900 words. The reaction to that edition was our highest ever.”

Designed for a phone, The Continent’s bite-size presentation of news reflects how people interact with information in this space. “We are also competing against Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, and TikTok: short, sharp, immediate reward things,” says Allison. “We have to mimic that approach.”

Replicating and benefiting from the natural ways in which people use WhatsApp, the focus is on building a small number of committed subscribers who will act as its distribution network. Here are some figures about the project:

- In an audience survey conducted at the end of 2020, 75% of respondents said they shared The Continent with at least two or three people each week.

- Approximately a third of the nearly 1,300 respondents said they shared it with at least six individuals weekly.

- The team now works on the basis that for every one of their 7,000 WhatsApp subscribers and 4,000-5,000 email subscribers there could be as many as seven onward shares. This would put the total audience of The Continent around 80,000 a week.

- The team has counted sign-ups on WhatsApp from 96 different countries.

Building such an organic distribution network helps build trust in The Continent’s journalism. “News is much more powerful if you receive it from someone you know,” says Allison. “It’s that personal connection. In terms of our journalism, people are more likely to associate it with trust and good feelings. These are the networks we want to build.”

The Continent’s coverage goes beyond Africa. On 31 October, it published a guest-edited issue which focused on the US elections featuring African writers, thinkers, and commentators who were asked to write in whatever language they wanted. It featured 11 different languages. “African media often gets siloed into covering just African stories,” says Allison. “There are very few, if any, African media houses with foreign correspondents. Almost all our international news comes via Western media outlets. That’s one of the paradigms we want to overturn.”

A Future Beyond WhatsApp?

Both Correio and The Continent are also experimenting with other messaging apps, and watching their audiences’ behavior closely in case there is a significant migration to Signal or Telegram.

WhatsApp’s limit on group sizes to restrict mass marketing remains a challenge, especially for the distribution of products like The Continent and 263Chat. “The app has made it very difficult to mass broadcast. There isn’t a technical solution we have found that isn’t very expensive,” explains Allison, who says they are signing up subscribers on Signal and via email, where there aren’t such restrictions.

With elections in 2023, technical issues for 263Chat could go beyond this. In 2019, the Zimbabwean government shut down access to the internet and messaging apps during protests against rising fuel prices.

Setting up a system outside the country which would still allow them to publish during a politically motivated shutdown is a priority, says Mugamu. But restrictions introduced by WhatsApp to curb automated or bulk messaging do not concern him. While the process of updating multiple groups by hand is laborious, creating a mass distribution network manually still allows 263Chat to reach audiences who have chosen to use data to download the e-paper at a time when resources are particularly limited in Zimbabwe. So long as this option remains, Mugamu and 263Chat will run with it.

Dealing with these technical limitations reinforces The Continent’s focus on building an audience of superusers who will act as its distribution network — without the title falling foul of WhatsApp’s restrictions, and lifting some of the burden of a manually operated mass broadcasting system. “Our head of distribution has said that we don’t want lots of subscribers; we want small numbers of committed subscribers, because our distribution network is our subscribers,” Allison says.

In light of recent security concerns over WhatsApp, Correio is considering whether Telegram could appeal to highly engaged subscribers. Monetizing messaging apps also has potential, according to Juan Torres. “It’s a hypothesis we would still bet on,” he says. “Could we charge for a subscription to a group or make it a premium product for subscribers?”

Not yet a year old, The Continent’s immediate plans are to ensure its core team are secured and production processes refined. Experiments with different language editions and commercial opportunities are also on the radar, according to Allison.

263Chat runs ads in its e-paper too, but will not give advertisers direct access to groups. It won’t set up a paywall either. Remaining free is crucial to reach the broadest audience possible, and keep a wider narrative of Zimbabwe open to all.

This piece first appeared on the website of the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism, and is republished here with permission.

Additional Reading

Maximizing Social Media in Your Newsroom: A Tipsheet on Distribution and Engaging Audiences

Distribution, Collaboration, and Freelancing: A GIJN Guide

Want To Help Investigative Startups in the Global South? Fund Them

Laura Oliver is a freelance journalist based in the UK. She has written for the Guardian, BBC, The Week, and more. She is a visiting lecturer in online journalism at City, University of London, and works as an audience strategy consultant for newsrooms.

Laura Oliver is a freelance journalist based in the UK. She has written for the Guardian, BBC, The Week, and more. She is a visiting lecturer in online journalism at City, University of London, and works as an audience strategy consultant for newsrooms.