Beirut Port the day after the explosion. Image: Shutterstock

On the evening of August 4, 2020, a devastating blast at the port in Beirut shook the Lebanese capital, leaving over 200 people dead, around 6,500 wounded, and rendering roughly 300,000 homeless. Analysis from the UK’s University of Sheffield revealed that the explosion was one of largest non-nuclear blasts in history.

Lebanon was already in the spotlight following a nationwide popular uprising and an ongoing economic crisis that has crippled the country. But the explosion made global headlines for the scale of the devastation and the subsequent investigations that revealed years of corruption at the port.

While there were a number of notable investigations into the blast, including by international news outlets, GIJN decided to look into three outlets whose investigations each played a pivotal role in understanding what led to the explosion, examining information and misinformation to determine how the Rhosus ship at the center of the blast and its deadly cargo were stuck at the port for so long.

These include a Bellingcat investigation for which the reporter was able to quickly verify what had happened at the port using open source tools, and a cross-border investigation by the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP) into how the explosive substance ammonium nitrate ended up at the port. Lastly, we spoke to a journalist from Lebanon’s local Al Jadeed television station, which had closely tracked the country’s ports, borders, and authorities for almost a decade, allowing them to scoop the competition after the blast.

Bellingcat: Open Source Video and Verification

“Social media feeds were flooded with images, videos, and reports of this gigantic explosion,” Nick Waters, a senior investigator at Bellingcat, told GIJN about the outburst of information that followed the blast. “And there were initially reports of multiple explosions all around the city and reports of airstrikes.”

Seeing the scale of the explosion, Waters decided to try to identify its source and magnitude, and whether allegations of an airstrike were founded.

Waters, a former British army officer, has provided open source analysis on a wide array of security issues in the Middle East. These include an attack on a Syrian Red Crescent convoy, an alleged chemical attack in the Syrian city of Hama, and a story analyzing whether Iran is hacking American drones flown over Iraq.

Waters was not surprised to see footage flooding social media channels, which he started to collect as a starting point for his investigative work. “In these kinds of incidents which are out of the ordinary, a significant chunk of the population was going to take out their phones to take photos or videos,” he said, adding that while he reached out to people he knew in Beirut for additional information and context, the amount of footage he found on Twitter alone was “slightly overwhelming.”

With the content collected not long after the explosion, Waters started to piece footage together and verify information to understand what just happened. “I tried to geolocate the videos, to establish if there were explosions in other locations to try to establish what blew up,” he said. “Watching the videos in slow motion, frame by frame, cross-referencing with other videos of the explosion — basically establishing a timeline.”

Several hours later he published What Just Blew Up In Beirut?

The story concluded: “The epicenter of the blast appears to have been the warehouse at 33.901353, 35.518835, and while the official explanation has yet to be confirmed, multiple sources on [sic] information point towards a shipment of 2,700 tons of ammonium nitrate that had been sitting in the port since 2013.”

In the days that followed, Waters found himself revisiting all that footage he collected. An incident this devastating is frequently accompanied by disinformation and misinformation. In Lebanon, while the authorities scrambled to figure out what had happened, the rumor mill went into overdrive: one video falsely showed a missile falling from the sky, while others shared a fake “thermal imaging” video.

Waters had already seen “over a hundred videos” at that point, none of which suggested that the explosion could be from an airstrike.

“The fakes that came later were a little bit unusual. Generally we don’t see such blatant attempts of fakery,” Waters told GIJN. “Usually we see people taking older videos from a different location claiming it was that event.”

Waters already had the original footage to cross-reference. One edited video showed a “missile” striking the port. He slowed down the video only to find out that the object was a bird. What about that “thermal” footage? “[It was] just a negative filter to make it more difficult to identify those fakes.”

Finally, claims that the blast was caused by an airstrike still persist to this day, with many residents in the vicinity saying they heard what resembled the sound of a jet. Waters told GIJN that from the material he collected, “there is no evidence or footage of a jet” from hundreds of angles.

He did, however, analyze footage where that sound was audible. The roar, he concluded, could have been an increase in intensity from the crackling of the fireworks that were in the same warehouse as the ammonium nitrate and the smaller explosion, the sound an intensifying fire can make as it pulls in air.

On August 7, Bellingcat published his findings, which countered all the false claims with evidence.

Once a niche area, this kind of forensic analysis has become more prominent with organizations like Human Rights Watch and major publications like The New York Times using it to enhance their investigative work. And while Waters agrees learning to utilize the many tools available to verify footage is valuable, he says the most important weapon in a reporter’s arsenal is contextual understanding.

“If you’ve already seen the videos before they’ve been faked, you have that contextual knowledge to know that what you’re seeing is a fake,” he said. “There is no really great tool to spot a fake video unless you have that contextual knowledge.”

Al Jadeed Television: The Paper Trail

When the explosion happened, local television station Al Jadeed was quick to mobilize. In fact, having investigated the country’s borders and customs officials for roughly a decade, the station’s investigative unit was perfectly placed to start digging into what had happened.

“We were able to shed light on all sorts of smuggling through the port and airport,” said Al Jadeed television reporter Layal Bou Moussa, adding that much of the information in their early reports was in fact collected over the years from people within the port and other institutions that wanted to expose corruption and mismanagement.

That earlier work meant Bou Moussa and her colleagues knew who to call, where to go, and who to talk to. On the team, everyone played a different role: she focused on getting legal and other official documents. “We started to collect information from all the security agencies, judges, experts, state lawyers — everyone — the moment it happened,” she told GIJN. “It was before anyone would have thought of what this could potentially lead to.”

Bou Moussa says that reaching out to officials at the onset of the explosion meant they were more accessible and easier to talk to. Working quickly also gave her access to people who would soon be indisposed: many of the officials were issued arrest warrants later that month. Further down the line, officials who felt they were in hot water would refer her to other officials as the blame game started heating up.

“We were the only ones able to speak to former transportation ministers and other officials after the explosion… because we did it right after it happened,” she said, adding that she was able to collect documents and letters from security agencies simply by asking soon after the blast.

Of course, it helped that Al Jadeed is a major television station in Lebanon that has hosted and interviewed prominent political officials over the years, but other major media outlets in Lebanon struggled to obtain much the same information in the weeks after the explosion. [Editor’s Note: In the spirit of keeping things “open source,” the television station’s investigative unit uploaded the files to a Google Drive folder, which they said was made accessible for any news agency or media outlet if requested.]

Bou Moussa, who studied law before turning to journalism, said she had used some of what she learned in her legal training to her advantage. “The crime scene is the most important space to find out what’s happened,” she said. “It’s the ‘black box.’”

But why would officials cooperate with a well-known muckraker? Bou Moussa doesn’t imagine it was purely altruistic. “I think they wanted to give information that would possibly alleviate responsibility from themselves,” she said.

After knocking on doors of over a dozen officials and collecting as many legal and official documents that she could, she began to piece everything together: how the ammonium nitrate ended up in the port warehouse for over a half a decade, who was involved, and — most importantly — who knew.

“I looked through all the files and documents – even the ones that might be false,” she said. “But I had to make sure I could verify each one.”

The work she conducted with her colleagues at Al Jadeed would become key to understanding the incident, and their reporting was picked up by outlets worldwide. Riad Kobaissi, her colleague in the investigative unit, was interviewed by numerous news agencies, like the Associated Press, about the explosion.

“People knew that this substance [ammonium nitrate] could lead to a massacre since 2014,” she told GIJN. “We were able to show how they [officials] tried to avoid taking responsibility for this crime, but at the same time showed exactly how they are responsible through the documents collected.”

“It showed that everyone knew but didn’t take on their responsibilities,” she said.

For Bou Moussa, reaching out to officials as soon as possible makes all the difference “before false narratives become prominent.” You’re bound to find “more truths” if you make contact with them early, she said.

OCCRP: Cross-Border Investigation

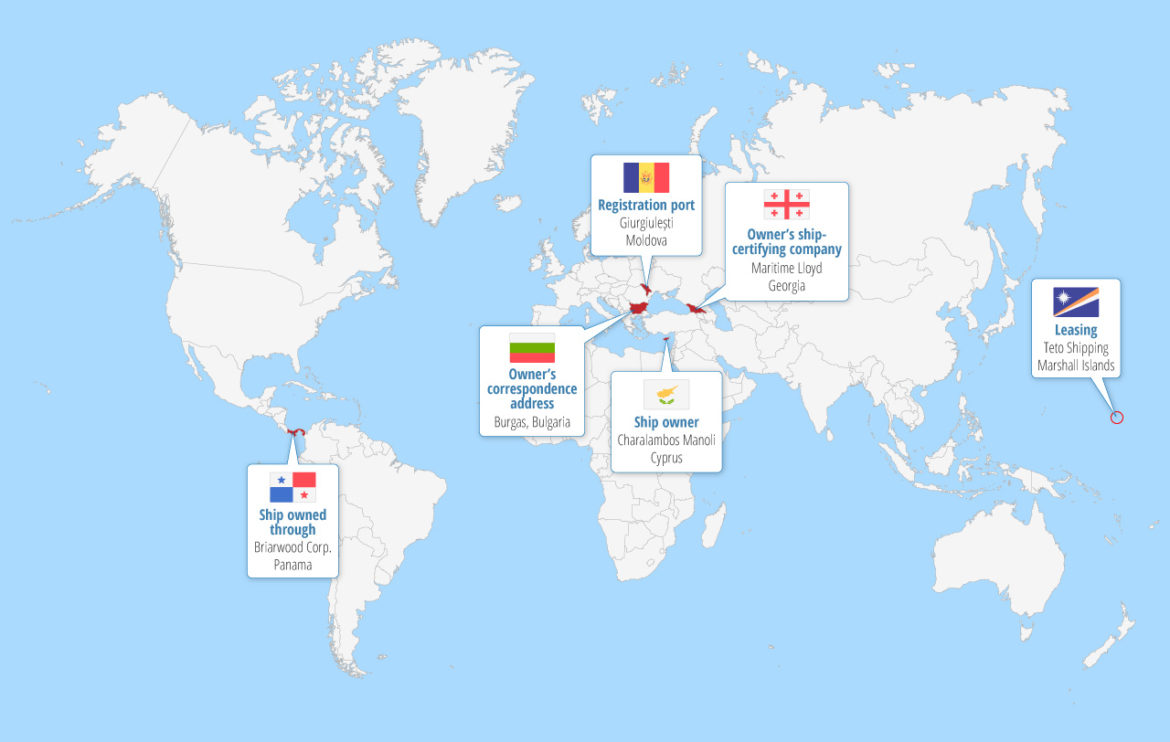

Offshore companies and convoluted ownership structures helped obscure the true ownership of the Rhosus. Graphic courtesy: OCCRP

While Bellingcat’s Waters worked on his own, and Bou Moussa collaborated with a team of four, the investigation published by the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP) involved over 20 reporters from 12 platforms across three continents.

Rana Sabbagh, OCCRP’s senior editor for Middle East and North Africa, said this cross-border investigation, though time-consuming, was key to revealing how the shipment of ammonium nitrate first reached the port in Beirut back in 2013.

“We wanted to see how that shipment arrived in Beirut. Whether it was intentional or whether it was diverted,” Sabbagh told GIJN.

The Rhosus, a ship of questionable seaworthiness that carried the explosive material into the port, had originally left Moldova planning to deliver its cargo to Mozambique. Somehow, it had ended up in Beirut, but the path it took to get there was complicated to investigate, with various owners and intermediaries involved in multiple countries.

Sabbagh consulted Aubrey Belford, an OCCRP editor based in Ukraine, who is well-versed in shipping.

The team would eventually consist of reporters in such countries as Lebanon, Georgia, Mozambique, Moldova, and Russia, who would communicate through a Signal group, daily Zoom calls, and by setting up a database to store and arrange their findings.

The multitude of languages used in the various documents they were analyzing and the sheer size of the team made the logistical side of the investigation challenging. “There were too many ‘cooks,’” Sabbagh said, although she added that having such an international team brought many positives.

“We had seven languages at our disposal,” she said. “The cultural diversity brought together a lot of added value to the story… You had local expertise.”

In less than a month, not only was the team able to reveal the Rhosus’ intended destination and what happened throughout its journey, they were also able to uncover its mysterious web of owners, and the different companies involved in the operation. Sabbagh says it would have taken her “two years” to do such an investigation on her own.

The investigation was published in numerous languages with different focuses across the different platforms involved.

A veteran Middle East journalist, Sabbagh sees cross-border investigations as “the future, in both a world more interconnected and in one with a journalism industry struggling to maintain its sustainability.”

Big investigations are “a costly process, and nobody can take it on on their own,” Sabbagh says. “Not everyone has the same skills. Someone might be good with tech, and another a maritime expert. You bring expertise together, complement each other, and create impact.”

On a similar theme, Forensic Architecture and the Egyptian media organization Mada Masr published on November 17 an investigation into the explosion, making its model, geolocated videos, and source material publicly available.

Four months after the explosion, the country’s official investigation appears to be lagging. While the probe into what caused the blast and who is responsible is being supported by the FBI and French explosive experts, the lack of an official narrative has left a hole that, at best, is being filled by investigative journalism and, at worst, by conspiracy theories.

The biggest question for everyone: How did this ticking time bomb sit right at the heart of the Lebanese capital for all these years?

Additional Reading

Using Twitter to Find People at the Scene of a Breaking Story

Kareem Chehayeb is a journalist and researcher in Beirut, Lebanon. He writes for independent media organization The Public Source and has had work published by The New York Times, Middle East Eye, and Business Insider.

Kareem Chehayeb is a journalist and researcher in Beirut, Lebanon. He writes for independent media organization The Public Source and has had work published by The New York Times, Middle East Eye, and Business Insider.