They were four of South Africa’s most respected investigative reporters, with long records of important exposés and loads of awards. And they had an elevated status on the country’s biggest and most powerful newspaper, the 100-year-old Sunday Times.

They were four of South Africa’s most respected investigative reporters, with long records of important exposés and loads of awards. And they had an elevated status on the country’s biggest and most powerful newspaper, the 100-year-old Sunday Times.

Mzilikazi wa Afrika’s first big story came when, on a bus from his small town home to the big city of Johannesburg, he overheard how easy it was for a foreigner to buy a new official identity. He set out to do it, and the Sunday Times splashed it on March 7, 1999, with the headline: “We Bust Fake ID Racket. For Just R300 You Can Buy a New Life.”

The Director General of Home Affairs at the time, Albert Mokoena, said that Wa Afrika had paid a bribe to get his story. So, Wa Afrika took a closer look at the man and a few months later reported that Mokoena was running a basketball team from his office and using his influence to give local identities to foreign players. Mokoena resigned.

Many courageous exposés were to follow in the next decade: the provincial director-general with a fake degree; the dark history of the kingpin of South African football; corruption in the country’s notorious arms deals.

In 2010 Wa Afrika was suddenly fired for running a business on the side and not declaring a conflict of interest. He came back a few years later to continue his run, this time forcing a senior cabinet minister out of her post for dishonesty.

Stephan Hofstatter’s career was equally stellar. He won a series of awards for major stories about land reform; the looting of a state food production program; mining lobbyists who were using fake identities to boost their case; corruption in the Land Bank. With Wa Afrika, he took down the powerful commissioner of police for a corrupt real estate deal for police HQ, then busted a senior cabinet minister whose wife had received secret payments from people doing business with her husband’s department.

Stephan Hofstatter’s career was equally stellar. He won a series of awards for major stories about land reform; the looting of a state food production program; mining lobbyists who were using fake identities to boost their case; corruption in the Land Bank. With Wa Afrika, he took down the powerful commissioner of police for a corrupt real estate deal for police HQ, then busted a senior cabinet minister whose wife had received secret payments from people doing business with her husband’s department.

The two reporters were joined by another up-and-coming star, Piet Rampedi, who seemed to have a line into the highest political circles, and financial journalist Rob Rose, who had broken some major business scandals.

They were riding so high that, in 2010, the rival Media24 news group offered to double their already-generous salaries if they crossed the floor. To keep them, the Sunday Times had to match the offer and give them special newsroom status.

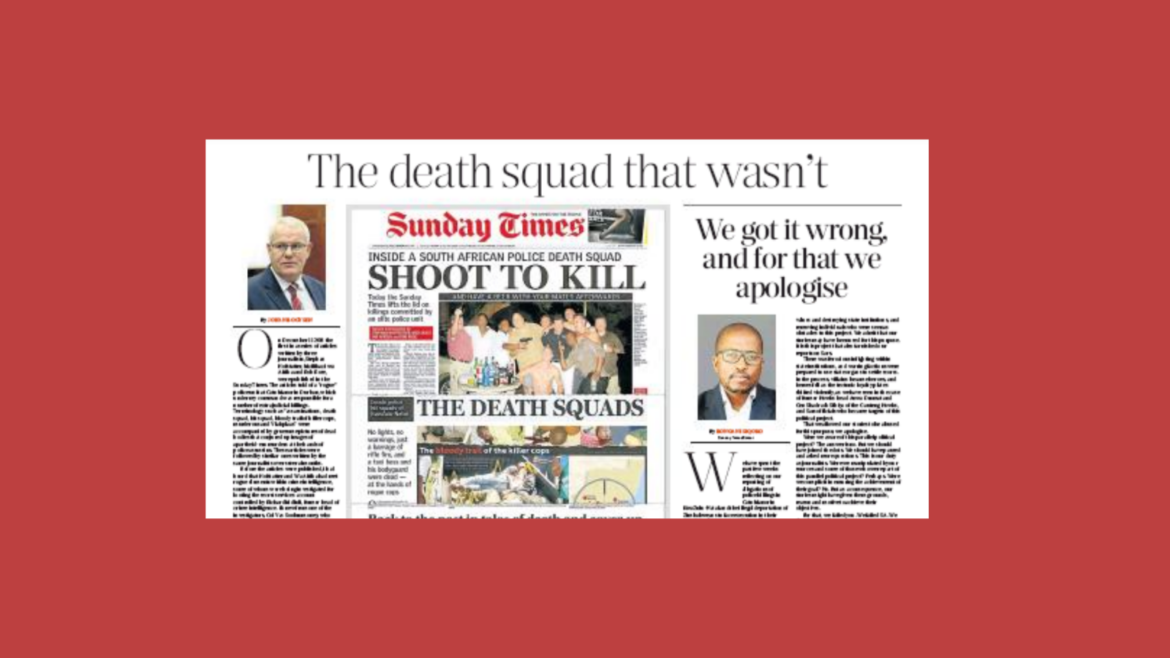

Then came a series of stories which appeared to be sensational, but which slowly fell apart. There was a police “death squad” in the township of Cato Manor; the involvement of senior policemen in the illegal rendition of Zimbabwean criminals; and a “rogue unit” in the country’s revenue services that was allegedly running a brothel, bugging the president, and generally running amok.

There was a pattern to these stories. In each case, they targeted individuals tackling what was called “state capture,” where corrupt individuals close to then-President Jacob Zuma seized control of key state institutions and positions to enable corruption. These stories were used to force those who blocked state capture out of office, replacing them with people more sympathetic to President Zuma. The Sunday Times ignored their protests and their views of why they were being targeted. When others began to report that the Sunday Time’s evidence was threadbare and they were being played by those around President Zuma, the paper brushed them off. They stuck with their narrative month after month and refused to even acknowledge counter-narratives.

It took six years, a change of editors and managers, three devastating Press Council rulings that ordered front page apologies, and key resignations from senior journalists before the Sunday Times finally admitted they had got the stories wrong, said they had been “played,” let the reporters go (some with payments to silence them), and said they were taking steps to prevent it from happening again.

It was a devastating moment for South African journalism. Yet they did not say who played them and what measures they were taking to fix their journalism. In the meanwhile, some of the country’s best public servants had their lives and careers ruined, and the paper had played a key role in enabling the corrupt state capture that characterized Zuma’s presidency.

That was why I wrote my book, So, for the Record: Behind the Headlines in an Era of State Capture. We had to know who “played” them and why they fell for it. If we were going to cure this problem — and fix our journalism — we had to have a diagnosis. A deep dive into what went wrong — an investigation into the investigators — would tell us not just about the Sunday Times, but the crisis in much of our journalism and what we had to do to get it back on track.

I had a rare perspective because I had been part of an independent panel of four called in by the Sunday Times in 2007 to look at internal newsroom problems. We interviewed dozens of staff members and made a series of recommendations to change what we saw as the toxic culture in the newsroom. But the report was buried and most of our suggestions ignored.

In my book, I showed how elements of the State Security Agency and Police Crime Intelligence, key elements in the state capture project, had fed the reporters false leads. And I showed the complicity of key business figures, and in particular the tobacco industry, which had been under pressure from tax authorities and eager to undermine the reporters.

These interests had tried to feed this disinformation to many different newspapers. Why was the Sunday Times the only one to fall for it?

What my probe revealed was that, under financial pressure to produce blockbuster stories, the paper had cut corners and ignored evidence that did not suit it. Its success over the years had made reporters and editors arrogant, with a sense of impunity and contempt for their critics. This was possible when they were powerful agenda-setters, but the rise of social media meant their influence had waned and they were no longer the gatekeepers. Everyone was going around or over the gate. They were slow to realize how much their world had changed.

Under financial pressure, the paper prioritized big splash front pages that boosted sales. But as the newsroom fell victim to cost-cutting, its capacity to produce the big weekly splash diminished. And that is when it had to take inside-page stories and sex them up for the front page. And once it had splashed the story, editors felt they had to stand by it — even as their world was crumbling.

Over the years, the newsroom had developed what they called “the Sunday Times treatment:” stories no more than 800 words, with a clear narrative, unequivocal in what they presented. Sunday readers wanted clarity, not complexity; they wanted heroes and villains. To achieve this, a string of editors saw their role as sharpening the stories. They removed the ifs and buts, the quotations marks and other qualifiers like the words alleged and claimed. It was a formula of proven success, as seen in their sales figures. But in the process allegations sometimes became assertions, claims often became evidence, and evidence became fact.

Editors and reporters developed a policy of putting allegations to the accused parties at the last moment. They said this was because the subjects of their stories had so often moved to preempt or prevent publication. But it meant that giving the right of reply became just a box-ticking exercise, as it was usually too late to give serious consideration and treatment to what their subjects said.

In case one thinks that all of our journalism is like this, I also tell the story of the great triumph of recent South African journalism, the GuptaLeaks story, where a cache of emails provided the hard evidence of state capture and helped bring down President Zuma. It is an intriguing tale of the best and most courageous journalism, and how it very nearly went wrong. At the heart of it were two non-traditional newsrooms: the specialist investigative unit, amaBhungane, and a website appropriately called the Daily Maverick.

What became clear to me is that most of our best journalism is now coming from stand-alone, specialist, non-profit, philanthropically-funded units, rather than traditional newsrooms.

If we are to grow our journalism, we have to support and build such specialist units. We have to rebuild journalism as a public service, rather than a profit-machine. And we have to embrace a journalism of complexity: one that accepts multiple, conflicting narratives rather than the simple, single story.

Editor’s Note: The Sunday Times’ “Cato Manor: Inside a South African Police Death Squad” won several awards, including the Taco Kuiper Award for Investigative Journalism, South Africa’s top honor for investigative reporting. In 2013, it shared first place in GIJN’s own Global Shining Light Awards, which are given for investigative reporting in developing and transitioning countries done under threat or duress. Due to reporting errors and other problems in the story, the Sunday Times in 2018 disavowed the work and returned all awards given to the team behind the story. In response, GIJN removed Cato Manor as a Global Shining Light Award winner. One of the story’s authors, Mzilikazi wa Afrika, served on the GIJN board from 2014 to 2017.

Anton Harber is the Caxton professor of journalism at the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, and the author of “So, for the Record: Behind the Headlines in an Era of State Capture” (Jonathan Ball, 2020). A GIJN board member, Harber was the founding co-editor of the Mail & Guardian and editor-in-chief of the independent news channel eNCA.

Anton Harber is the Caxton professor of journalism at the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, and the author of “So, for the Record: Behind the Headlines in an Era of State Capture” (Jonathan Ball, 2020). A GIJN board member, Harber was the founding co-editor of the Mail & Guardian and editor-in-chief of the independent news channel eNCA.